This document discusses inner product spaces and some of their key properties:

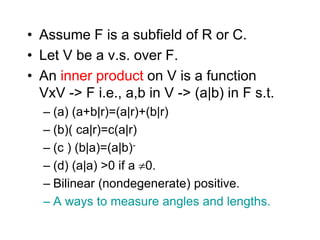

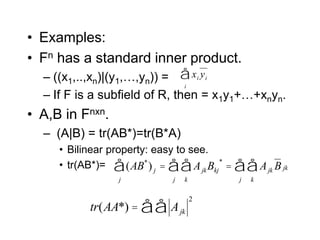

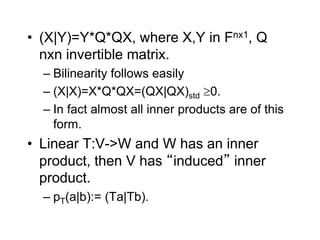

1. It defines an inner product and provides examples such as the standard inner product on Fn.

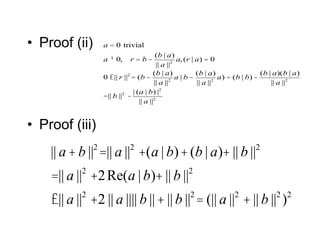

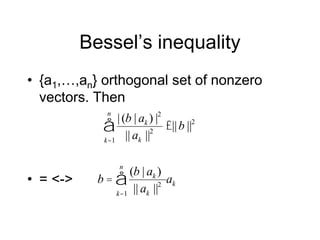

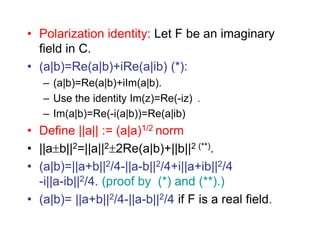

2. It proves important inequalities for inner product spaces like Cauchy-Schwarz and the triangle inequality.

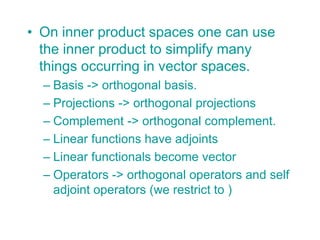

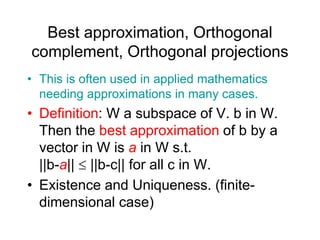

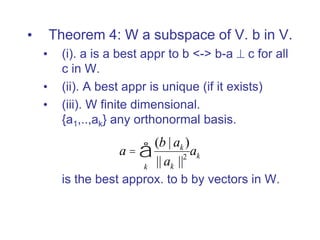

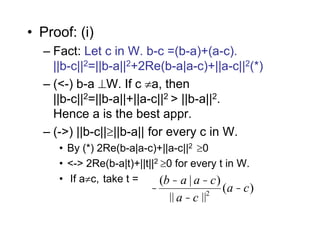

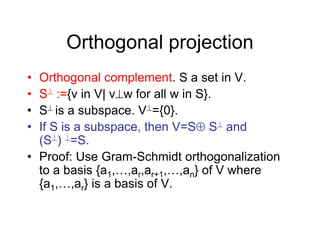

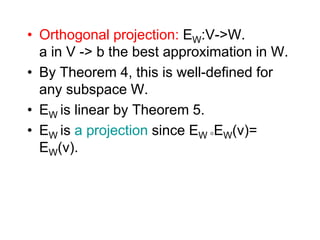

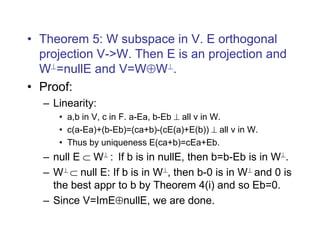

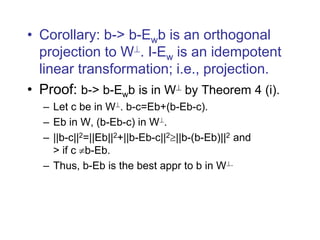

3. It discusses how an inner product allows the use of orthogonal bases, orthogonal projections, and orthogonal complements to simplify problems in vector spaces.

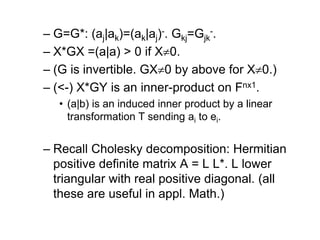

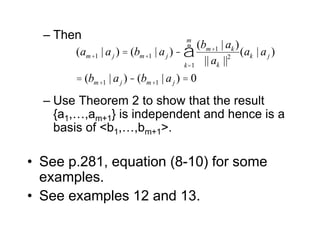

![• (a) For any basis B={a1,…,an}, there is

an inner-product s.t. (ai|aj)=ij.

– Define T:V->Fn s.t. ai -> ei.

– Then pT(ai|aj)=(ei|ej)= ij.

• (b) V={f:[0,1]->C| f is continuous }.

– (f|g)= 0

1 fg- dt for f,g in V is an inner

product.

– T:V->V defined by f(t) -> tf(t) is linear.

– pT(f,g)= 0

1tftg- dt=0

1t2fg- dt is an inner

product.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lin2007iich8pt1-230731115610-47d586cd/85/lin2007IICh8pt1-ppt-5-320.jpg)

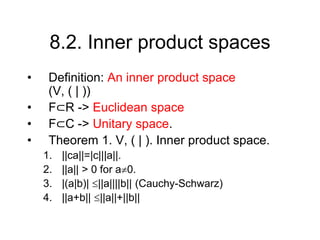

![• When V is finite-dimensional, inner

products can be classified.

• Given a basis B={a1,…,an} and any

inner product ( | ):

(a|b) = Y*GX for X=[a]B, Y=[b]B

– G is an nxn-matrix and G=G*, X*GX0 for

any X, X0.

• Proof: (->) Let Gjk=(ak|aj).

a = xk

k

å ak,b = y jaj

j

å

(a |b) = ( xk

k

å ak,b) = xk

k

å y j (ak | aj

j

å ) = Y*

GX](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lin2007iich8pt1-230731115610-47d586cd/85/lin2007IICh8pt1-ppt-7-320.jpg)