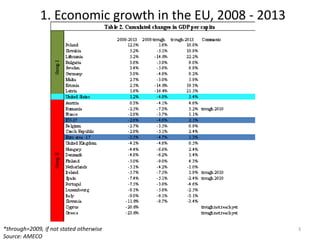

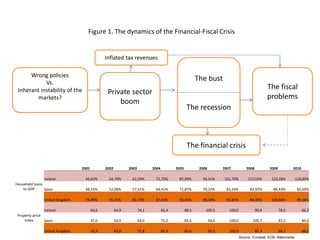

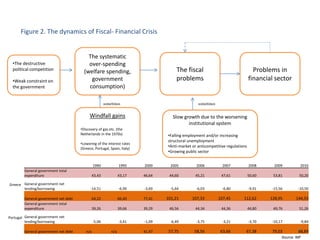

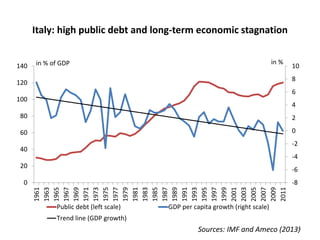

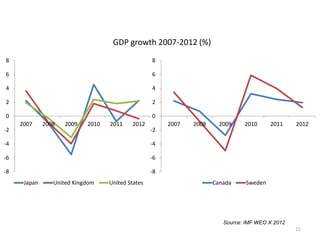

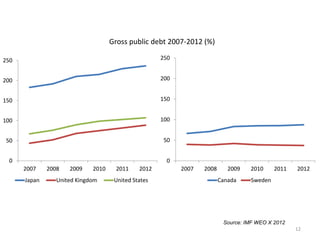

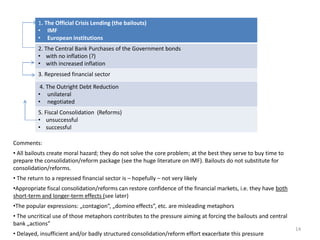

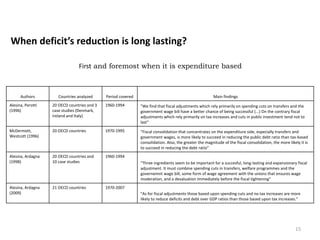

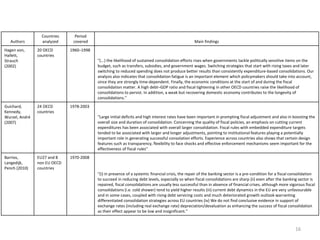

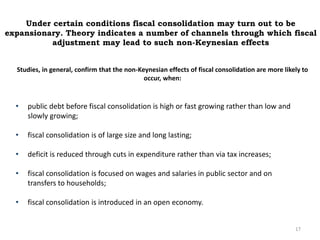

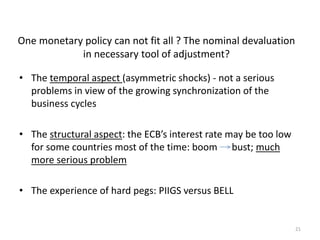

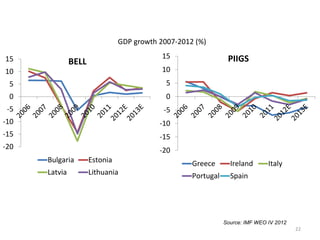

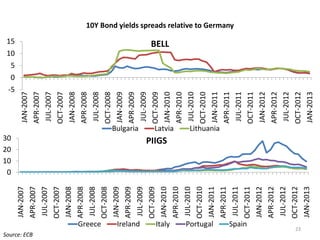

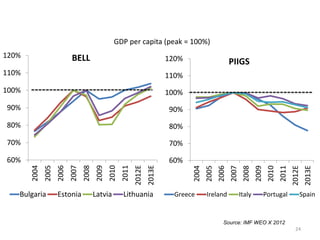

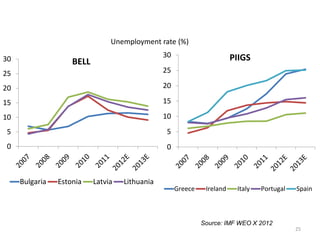

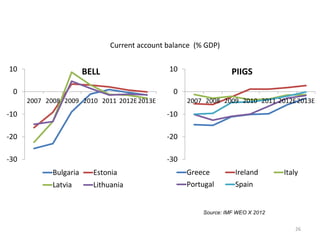

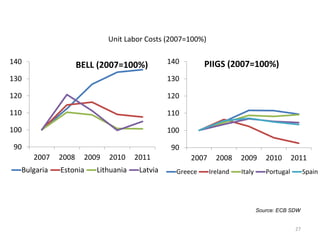

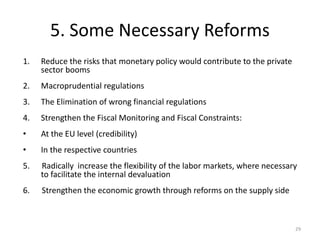

This document summarizes a presentation on problems and solutions related to the Euro. It discusses economic growth in the EU from 2008-2013, reasons for deep recessions in some Eurozone countries including financial and fiscal crises, policy responses and their impact on GDP growth, issues related to the Eurozone crisis, and necessary solutions. The presentation contains graphs and tables displaying economic indicators for various countries.