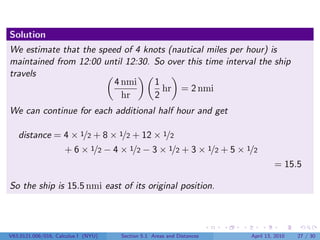

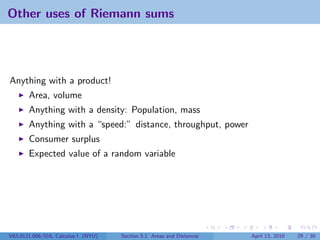

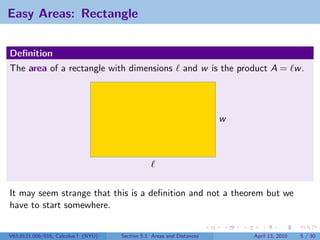

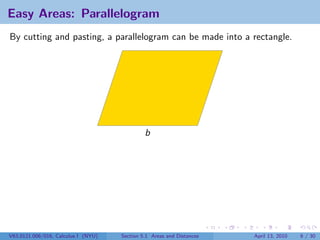

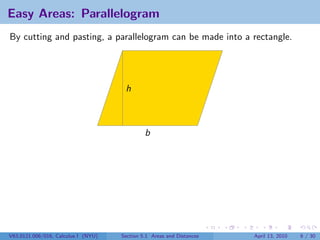

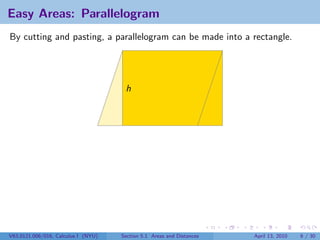

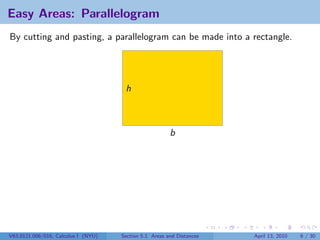

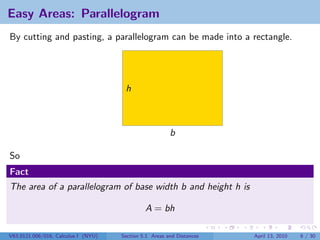

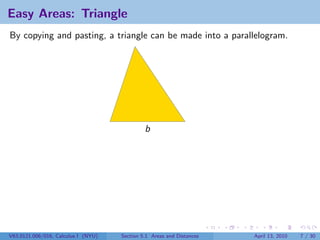

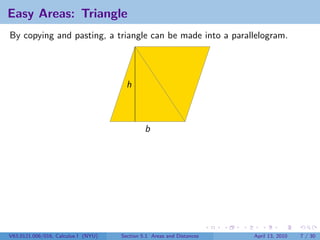

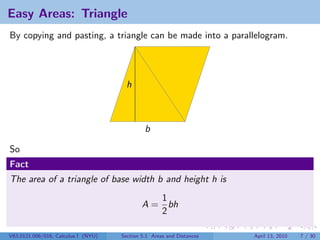

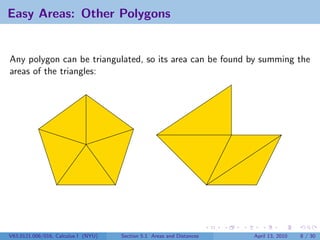

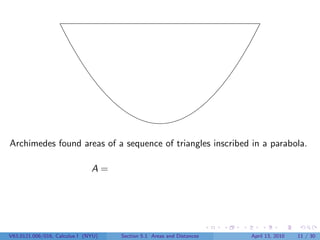

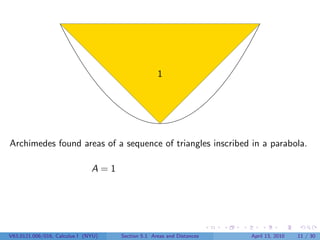

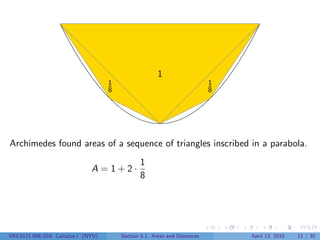

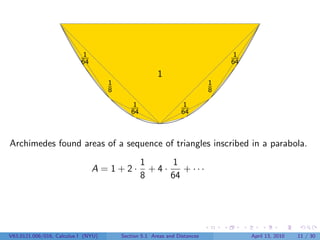

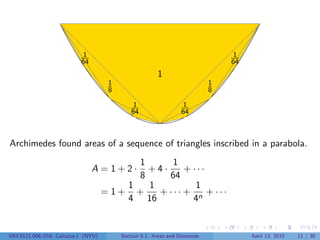

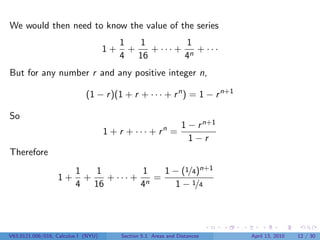

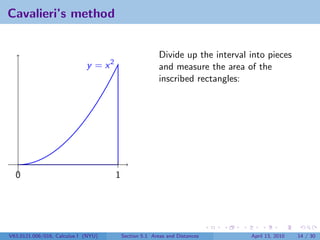

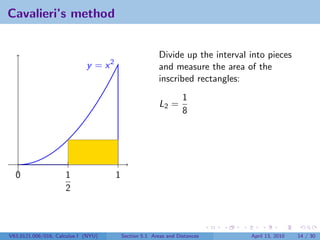

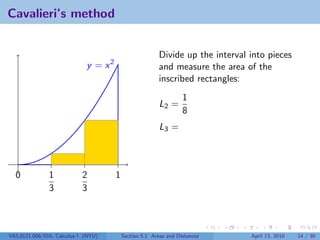

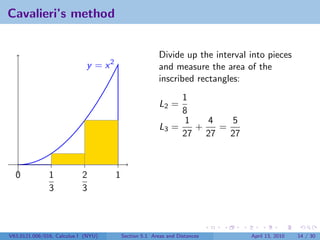

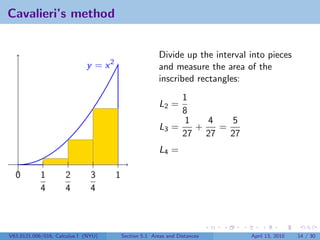

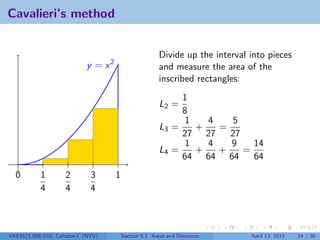

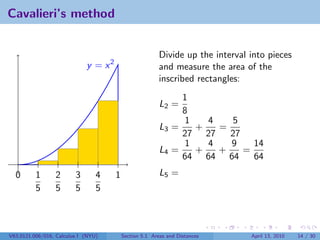

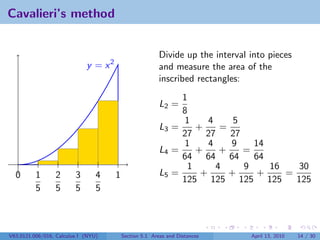

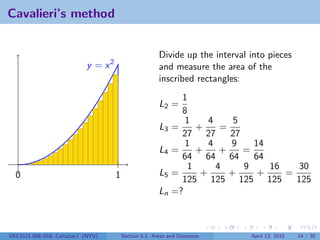

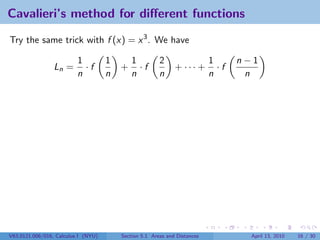

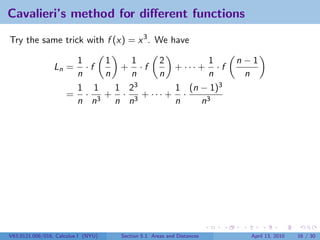

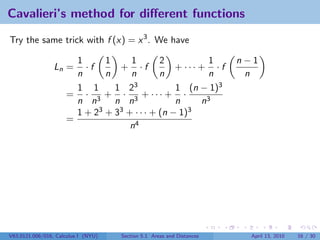

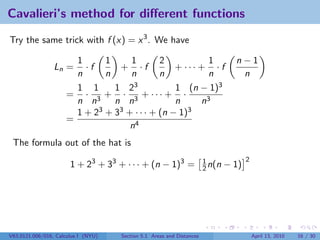

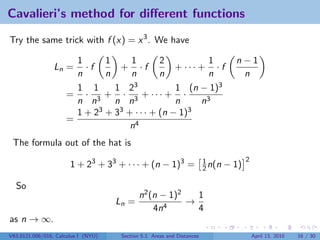

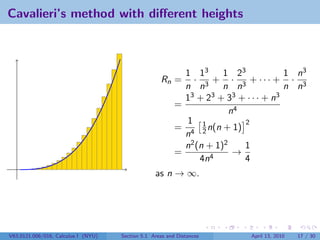

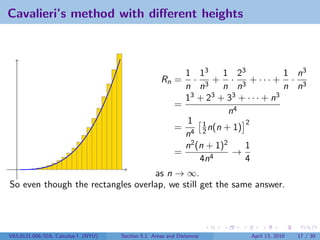

This document outlines the content of a Calculus I course at New York University, focusing on areas and distances as of April 13, 2010. It includes objectives such as computing area using rectangles and determining total distance traveled by a particle. The document also discusses mathematical concepts from historical figures like Euclid, Archimedes, and Cavalieri, and techniques for calculating areas of various shapes.

![What is Ln ?

1

Divide the interval [0, 1] into n pieces. Then each has width .

n

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 15 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-38-320.jpg)

![What is Ln ?

1

Divide the interval [0, 1] into n pieces. Then each has width . The

n

rectangle over the ith interval and under the parabola has area

2

1 i −1 (i − 1)2

· = .

n n n3

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 15 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-39-320.jpg)

![What is Ln ?

1

Divide the interval [0, 1] into n pieces. Then each has width . The

n

rectangle over the ith interval and under the parabola has area

2

1 i −1 (i − 1)2

· = .

n n n3

So

1 22 (n − 1)2 1 + 22 + 32 + · · · + (n − 1)2

Ln = + 3 + ··· + =

n3 n n3 n3

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 15 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-40-320.jpg)

![What is Ln ?

1

Divide the interval [0, 1] into n pieces. Then each has width . The

n

rectangle over the ith interval and under the parabola has area

2

1 i −1 (i − 1)2

· = .

n n n3

So

1 22 (n − 1)2 1 + 22 + 32 + · · · + (n − 1)2

Ln = + 3 + ··· + =

n3 n n3 n3

The Arabs knew that

n(n − 1)(2n − 1)

1 + 22 + 32 + · · · + (n − 1)2 =

6

So

n(n − 1)(2n − 1)

Ln =

6n3

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 15 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-41-320.jpg)

![What is Ln ?

1

Divide the interval [0, 1] into n pieces. Then each has width . The

n

rectangle over the ith interval and under the parabola has area

2

1 i −1 (i − 1)2

· = .

n n n3

So

1 22 (n − 1)2 1 + 22 + 32 + · · · + (n − 1)2

Ln = + 3 + ··· + =

n3 n n3 n3

The Arabs knew that

n(n − 1)(2n − 1)

1 + 22 + 32 + · · · + (n − 1)2 =

6

So

n(n − 1)(2n − 1) 1

Ln = →

6n3 3

as n → ∞.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 15 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-42-320.jpg)

![Cavalieri’s method in general

Let f be a positive function defined on the interval [a, b]. We want to find the area

between x = a, x = b, y = 0, and y = f (x).

b−a

For each positive integer n, divide up the interval into n pieces. Then ∆x = .

n

For each i between 1 and n, let xi be the nth step between a and b. So

x0 = a

b−a

x1 = x0 + ∆x = a +

n

b−a

x2 = x1 + ∆x = a + 2 ·

n

······

b−a

xi = a + i ·

n

······

a b b−a

x0 x1 x2 . . . xi xn−1xn xn = a + n · =b

n

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 19 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-51-320.jpg)

![Cavalieri’s method in general

Let f be a positive function defined on the interval [a, b]. We want to find the area

between x = a, x = b, y = 0, and y = f (x).

b−a

For each positive integer n, divide up the interval into n pieces. Then ∆x = .

n

For each i between 1 and n, let xi be the nth step between a and b. So

x0 = a

b−a

x1 = x0 + ∆x = a +

n

b−a

x2 = x1 + ∆x = a + 2 ·

n

······

b−a

xi = a + i ·

n

······

a b b−a

x0 x1 x2 . . . xi xn−1xn xn = a + n · =b

n

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 19 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-52-320.jpg)

![Cavalieri’s method in general

Let f be a positive function defined on the interval [a, b]. We want to find the area

between x = a, x = b, y = 0, and y = f (x).

b−a

For each positive integer n, divide up the interval into n pieces. Then ∆x = .

n

For each i between 1 and n, let xi be the nth step between a and b. So

x0 = a

b−a

x1 = x0 + ∆x = a +

n

b−a

x2 = x1 + ∆x = a + 2 ·

n

······

b−a

xi = a + i ·

n

······

a b b−a

x0 x1 x2 . . . xi xn−1xn xn = a + n · =b

n

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 19 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-53-320.jpg)

![Cavalieri’s method in general

Let f be a positive function defined on the interval [a, b]. We want to find the area

between x = a, x = b, y = 0, and y = f (x).

b−a

For each positive integer n, divide up the interval into n pieces. Then ∆x = .

n

For each i between 1 and n, let xi be the nth step between a and b. So

x0 = a

b−a

x1 = x0 + ∆x = a +

n

b−a

x2 = x1 + ∆x = a + 2 ·

n

······

b−a

xi = a + i ·

n

······

a b b−a

x0 x1 x2 . . . xi xn−1xn xn = a + n · =b

n

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 19 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-54-320.jpg)

![Cavalieri’s method in general

Let f be a positive function defined on the interval [a, b]. We want to find the area

between x = a, x = b, y = 0, and y = f (x).

b−a

For each positive integer n, divide up the interval into n pieces. Then ∆x = .

n

For each i between 1 and n, let xi be the nth step between a and b. So

x0 = a

b−a

x1 = x0 + ∆x = a +

n

b−a

x2 = x1 + ∆x = a + 2 ·

n

······

b−a

xi = a + i ·

n

······

a b b−a

x0 x1 x2 . . . xi xn−1xn xn = a + n · =b

n

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 19 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-55-320.jpg)

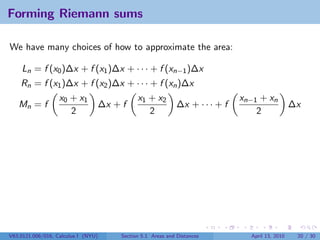

![Forming Riemann sums

We have many choices of how to approximate the area:

Ln = f (x0 )∆x + f (x1 )∆x + · · · + f (xn−1 )∆x

Rn = f (x1 )∆x + f (x2 )∆x + · · · + f (xn )∆x

x0 + x1 x1 + x2 xn−1 + xn

Mn = f ∆x + f ∆x + · · · + f ∆x

2 2 2

In general, choose ci to be a point in the ith interval [xi−1 , xi ]. Form the

Riemann sum

Sn = f (c1 )∆x + f (c2 )∆x + · · · + f (cn )∆x

n

= f (ci )∆x

i=1

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 20 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-57-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a b

x1

matter what choice of ci we

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-58-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a x1 b

x2

matter what choice of ci we

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-59-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a x1 x2 b

x3

matter what choice of ci we

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-60-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a x1 x2 x3 b

x4

matter what choice of ci we

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-61-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a x x x x x

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 b5

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-62-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a x x x x x x

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 b6

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-63-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a x x x x x x x

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 b7

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-64-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

ax x x x x x x x

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 b8

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-65-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

ax x x x x x x x x

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8b9

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-66-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a x x x x x x x x x xb

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-67-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

ax x x x x x x x x x xb

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-68-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

ax x x x x x x x xx x xb

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 101112

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-69-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

ax x x x x x x x xx x x xb

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 12

11 13

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-70-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

ax x x x x x x x xx x x x xb

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 12 14

11 13

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-71-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

ax x x x x x x x xx x x x x xb

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 12 14

11 13 15

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-72-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

axxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxb

matter what choice of ci we 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 12 14 16

11 13 15

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-73-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxb

x1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 12 14 16

matter what choice of ci we 11 13 15 17

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-74-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxb

x1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8x10 12 14 16 18

matter what choice of ci we 9 11 13 15 17

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-75-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxb

x12345678910 12 14 16 18

x 11 13 15 17 19

matter what choice of ci we

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-76-320.jpg)

![Theorem of the Day

Theorem

If f is a continuous function or

has finitely many jump

discontinuities on [a, b], then

n

lim Sn = lim f (ci )∆x

n→∞ n→∞

i=1

exists and is the same value no

a xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxb

x123456789101214161820

x 1113151719

matter what choice of ci we

made.

V63.0121.006/016, Calculus I (NYU) Section 5.1 Areas and Distances April 13, 2010 21 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lesson22-areasanddistancesslides-100413152044-phpapp02/85/Lesson-22-Areas-and-Distances-77-320.jpg)