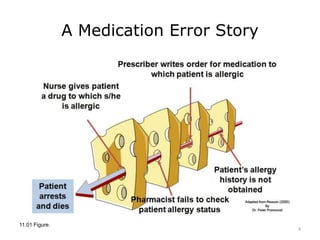

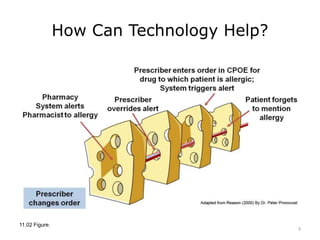

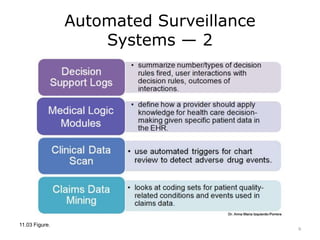

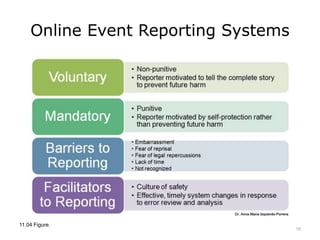

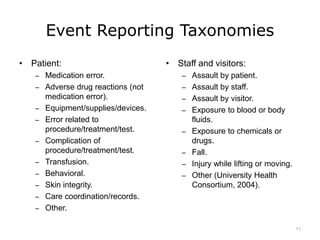

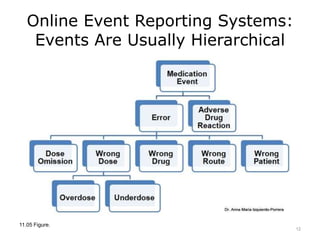

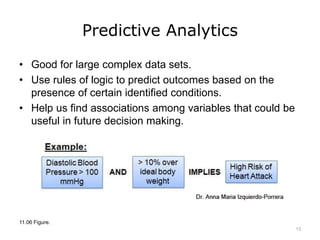

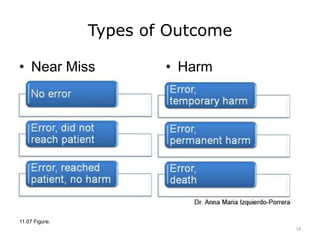

This lecture discusses how health information technology can help facilitate error reporting and analysis to improve patient safety. It presents three key HIT mechanisms: automated surveillance systems, online event reporting systems, and predictive analytics/data modeling. The lecture also emphasizes the importance of a culture of safety that encourages open discussion and learning from mistakes without blame. Error reports are analyzed using a risk assessment model to distinguish near misses from events that cause patient harm.