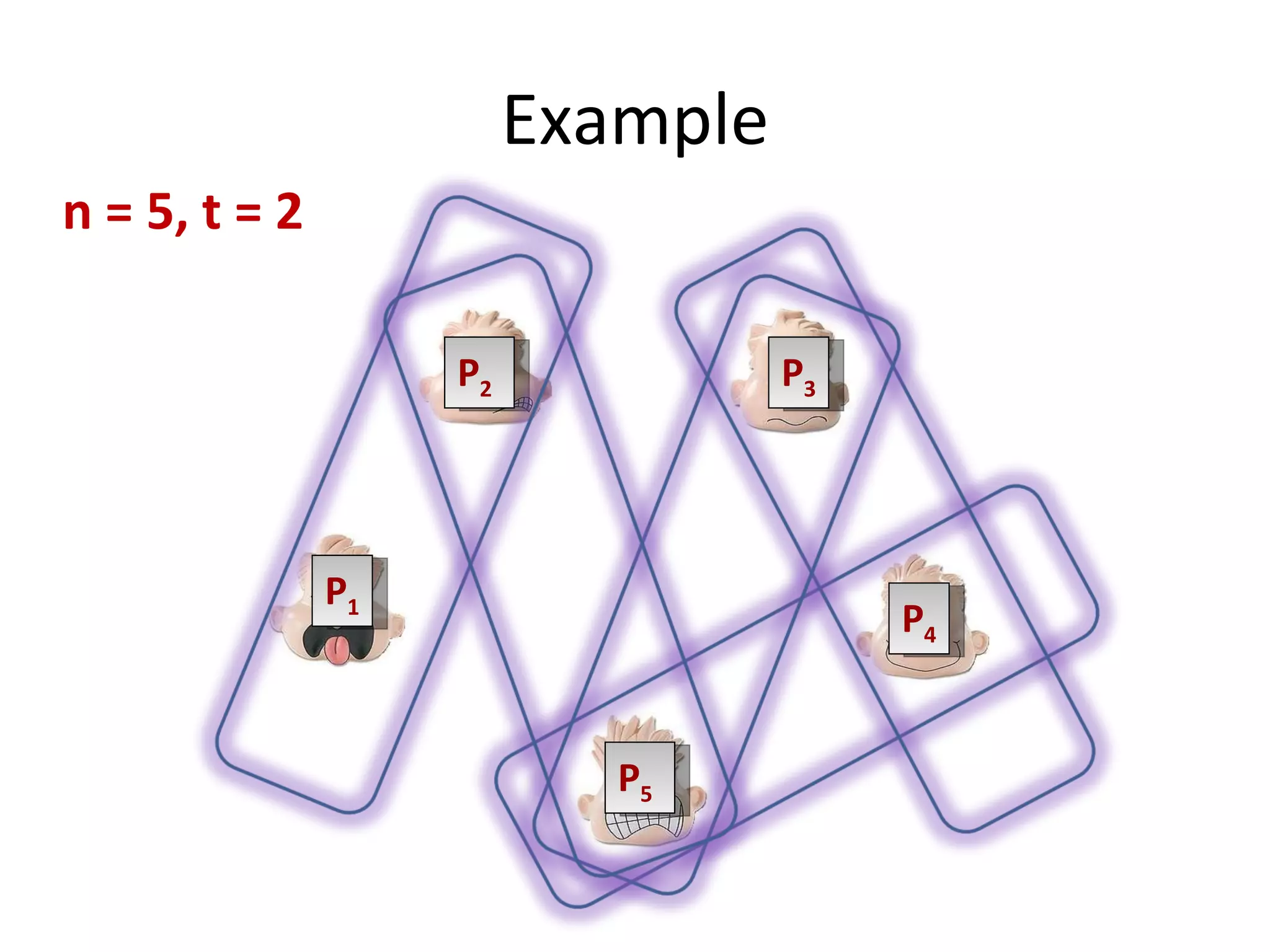

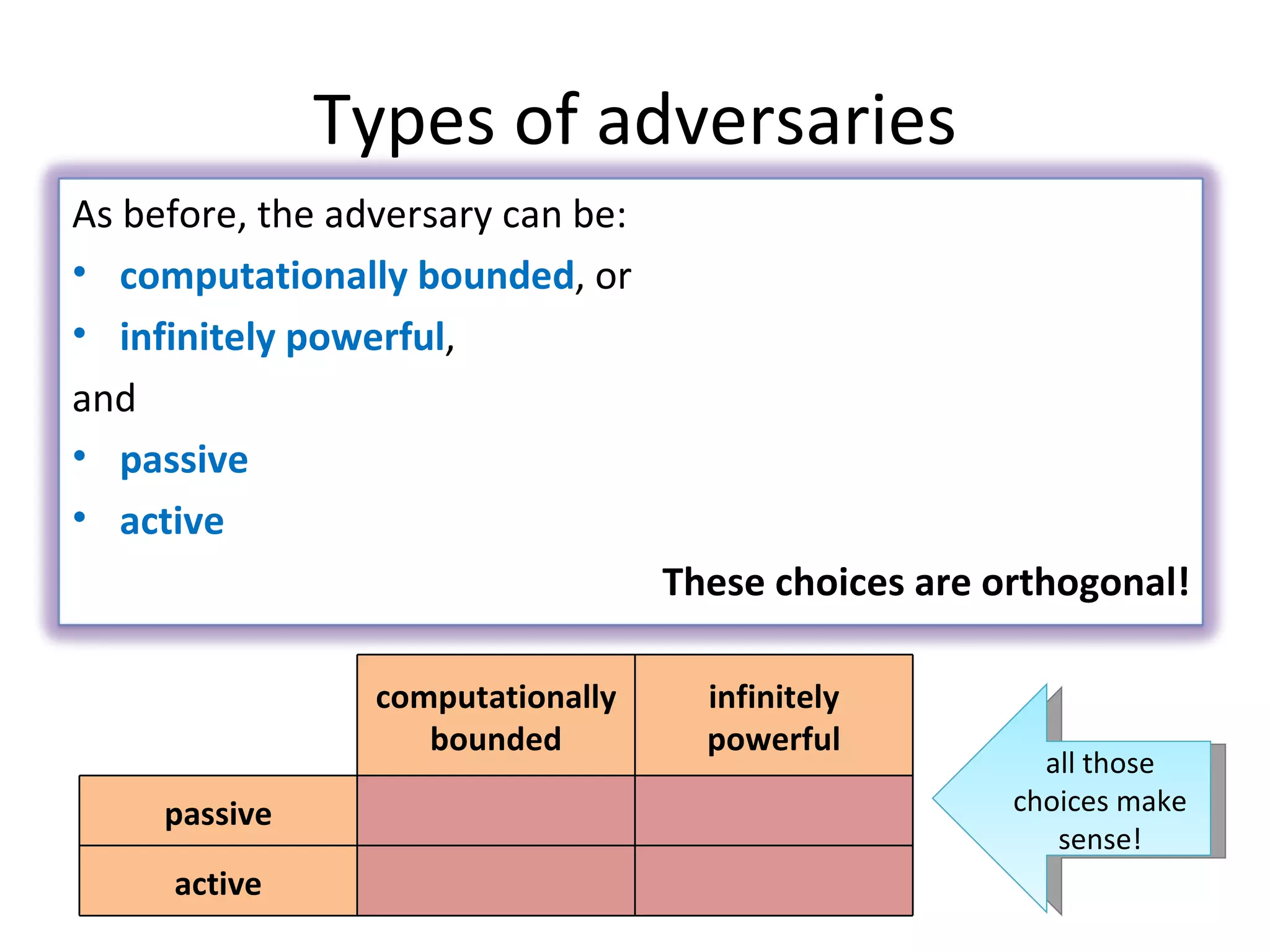

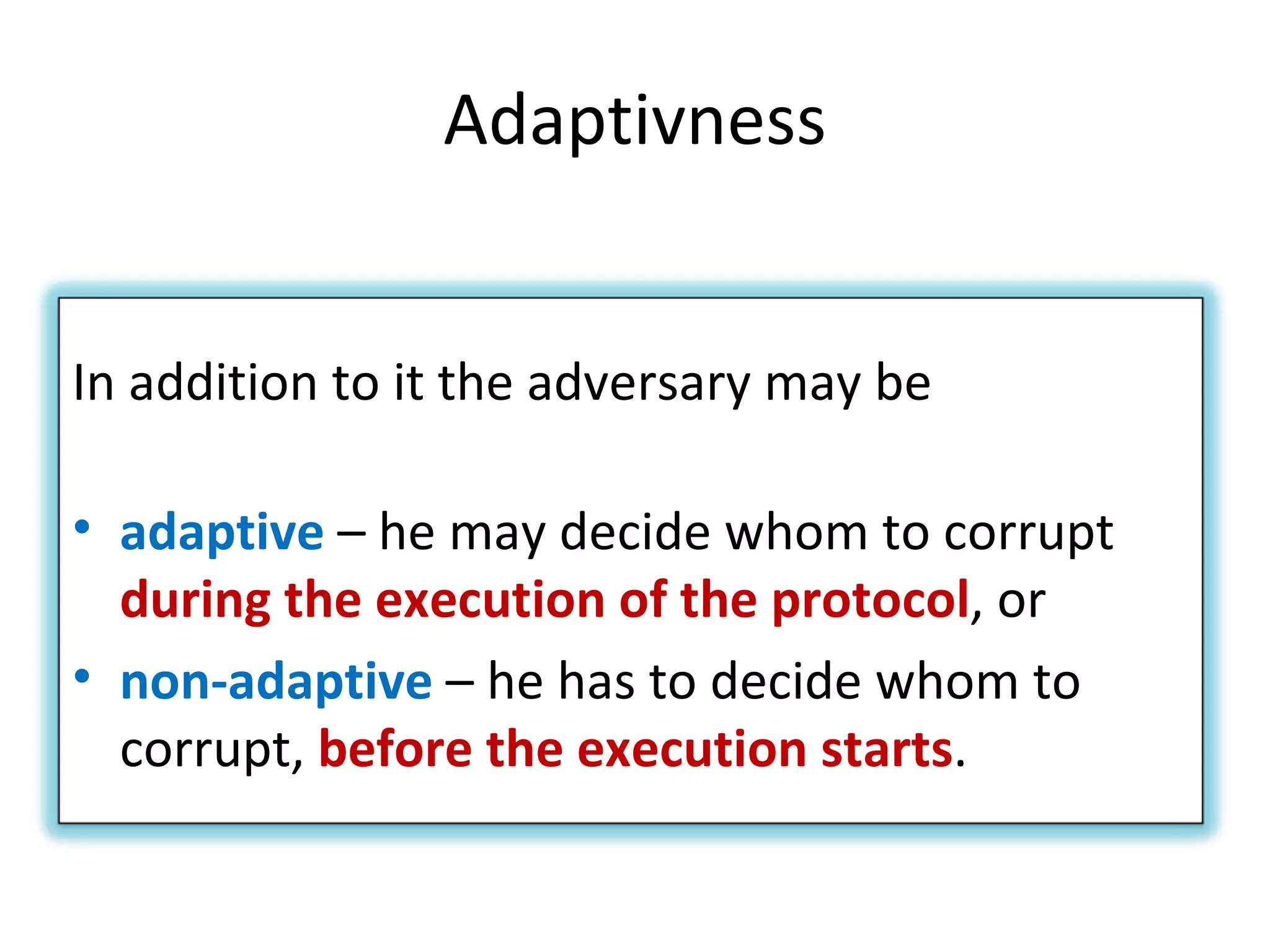

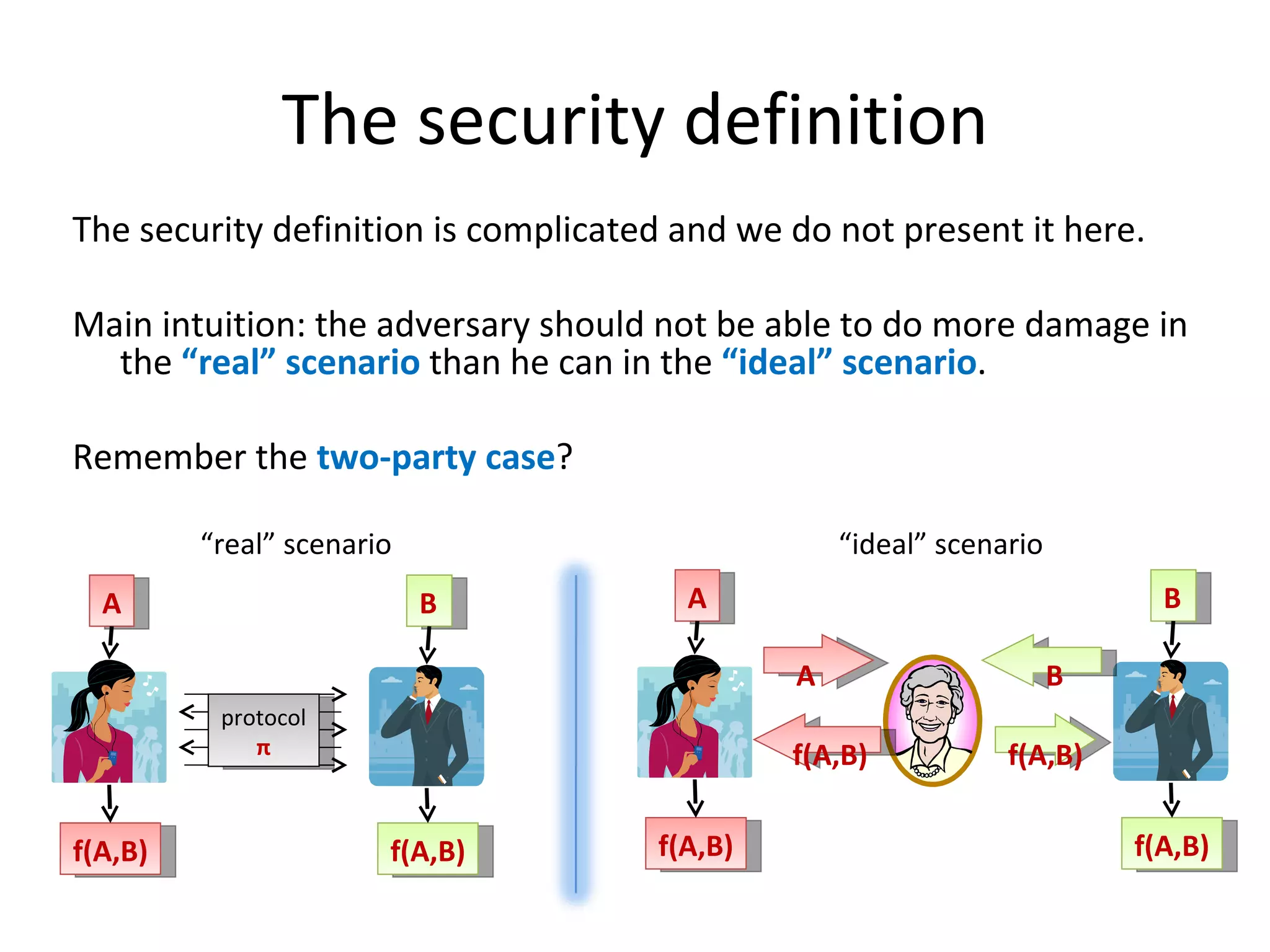

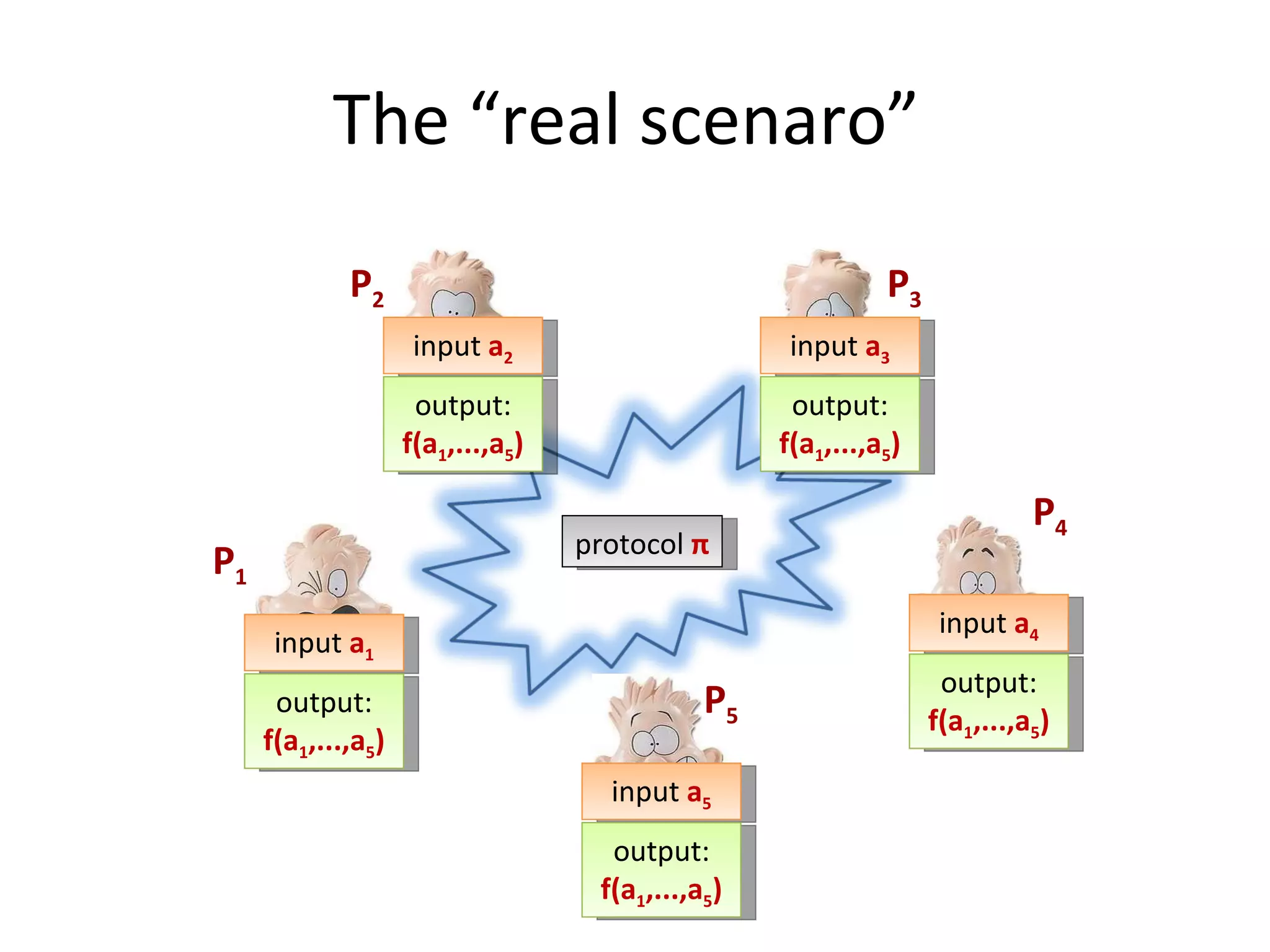

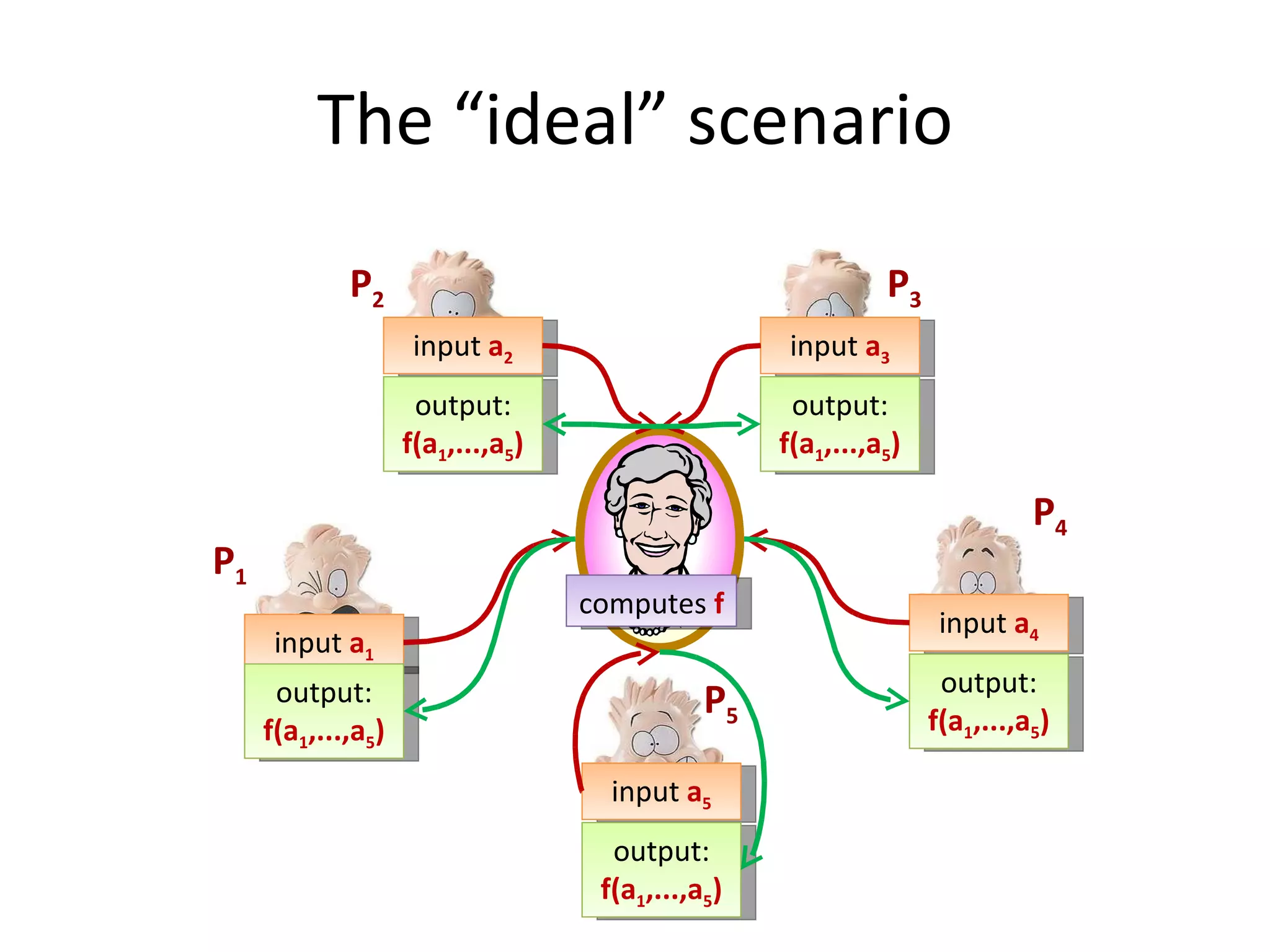

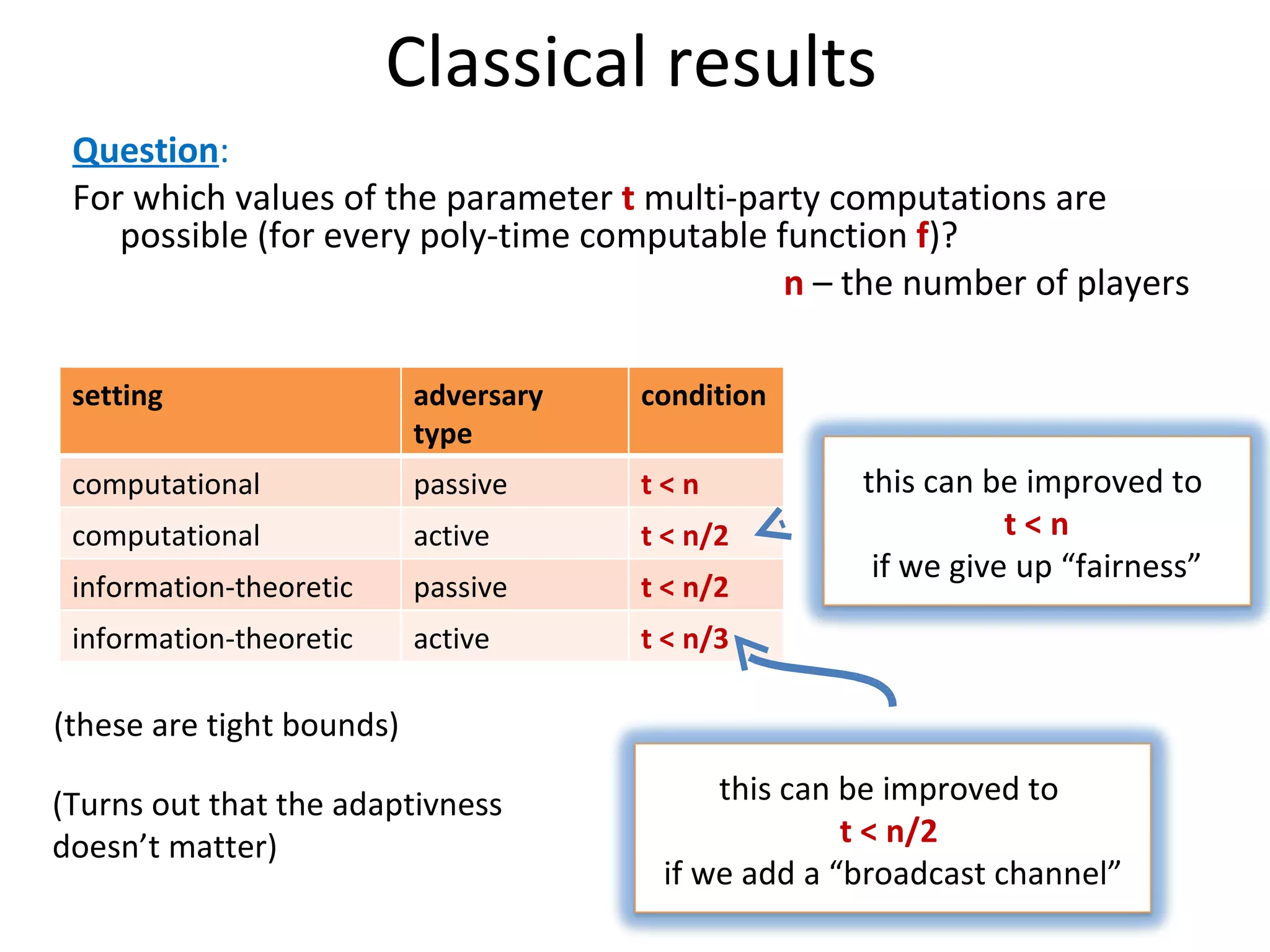

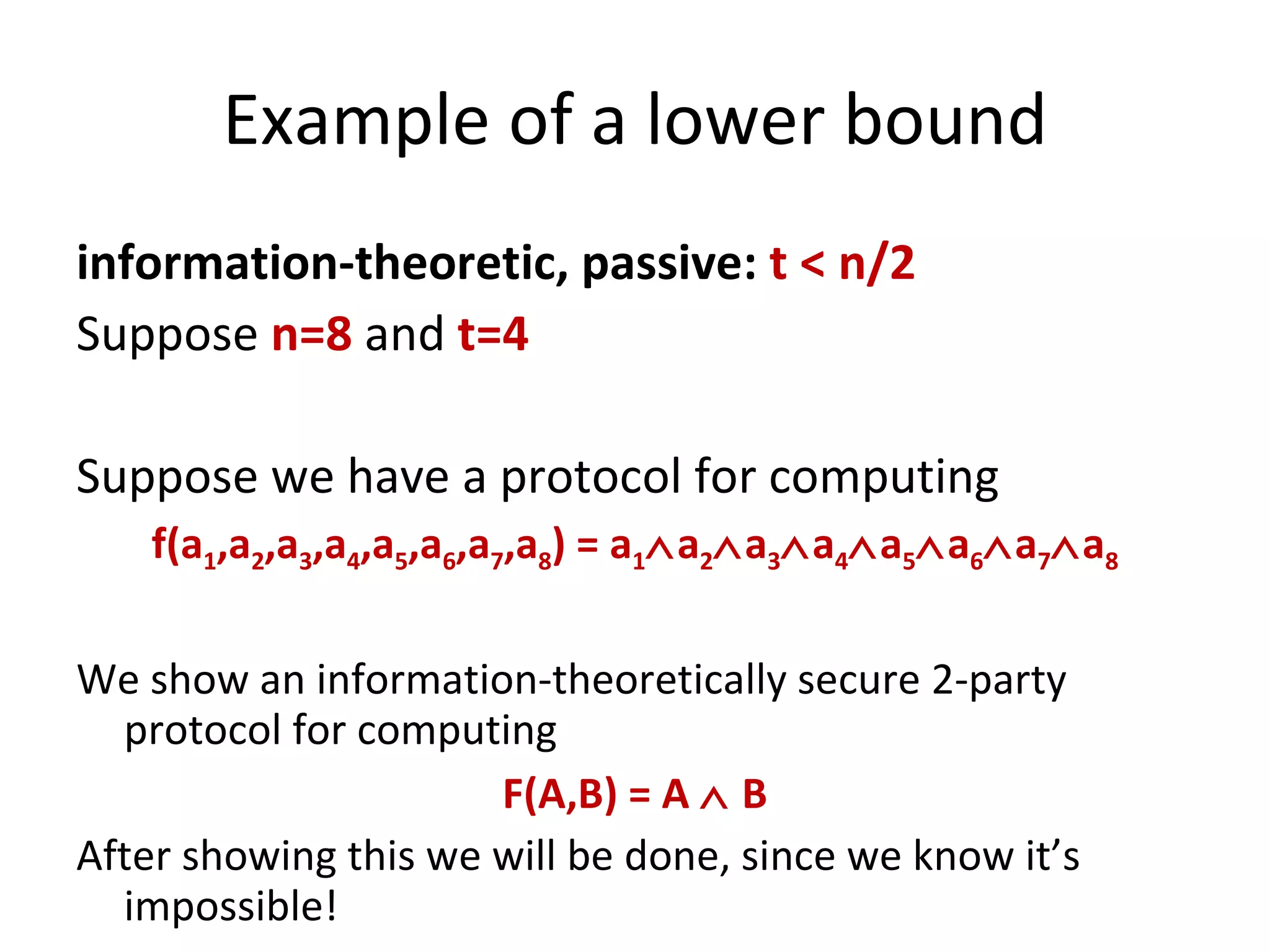

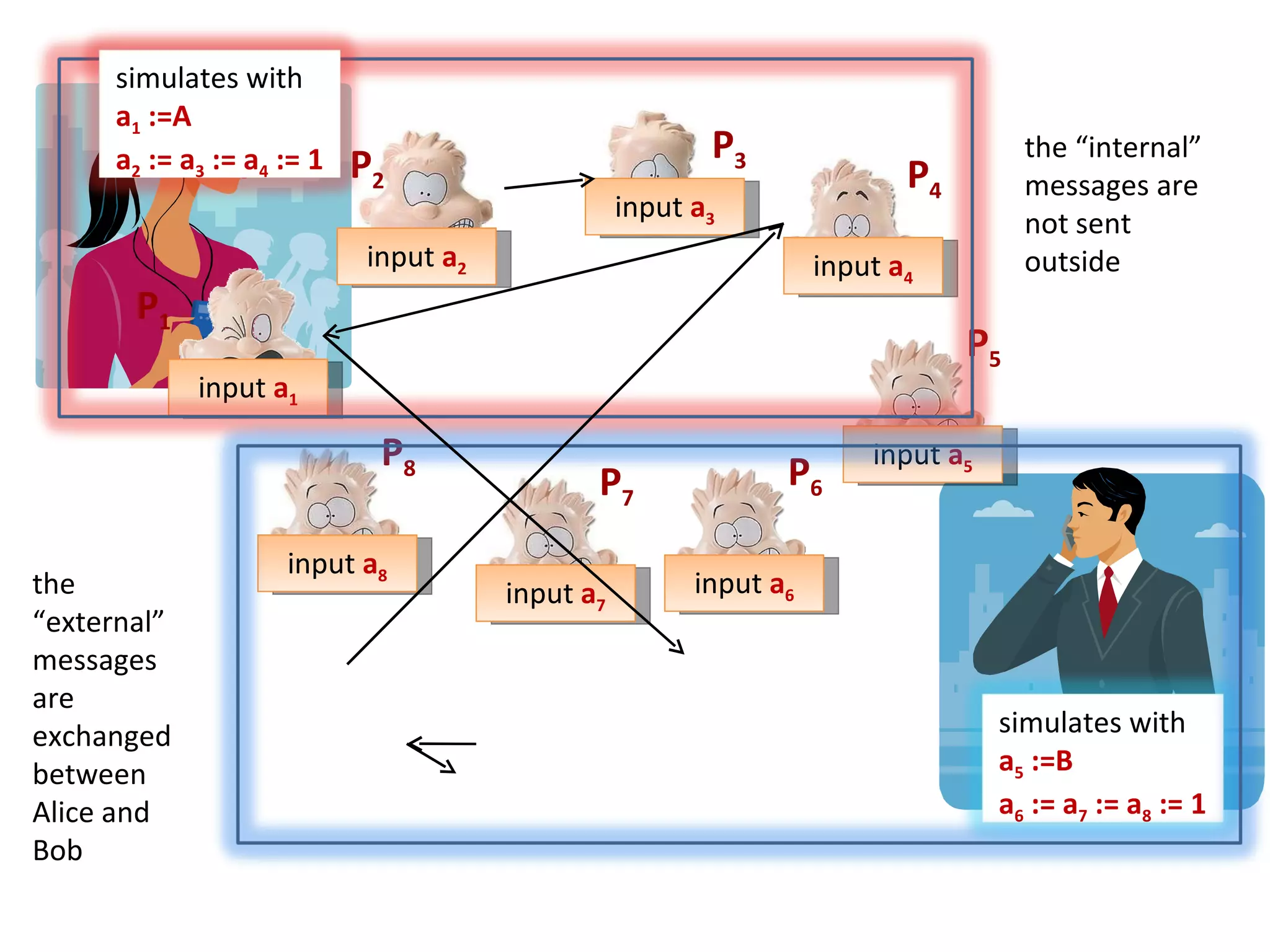

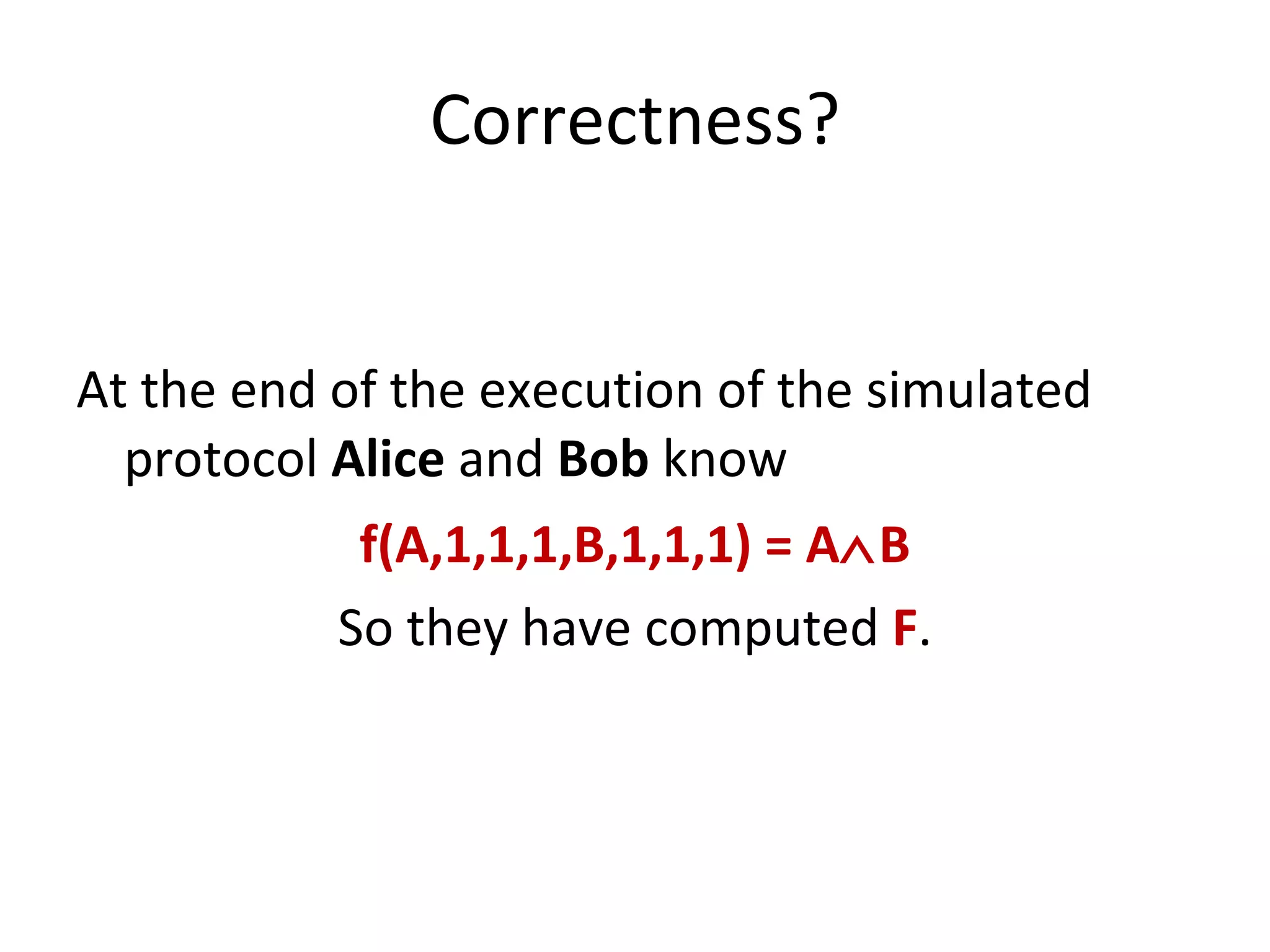

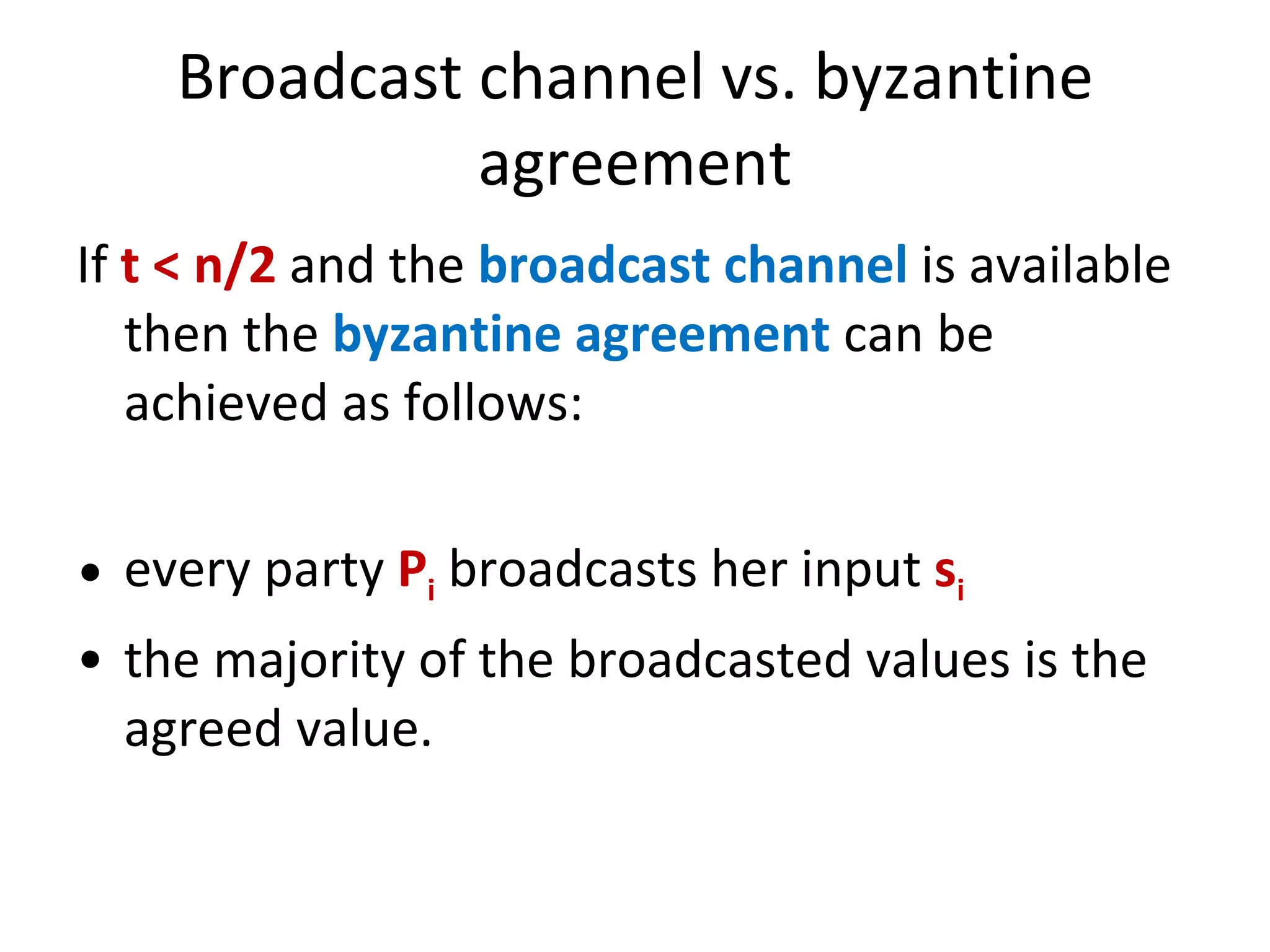

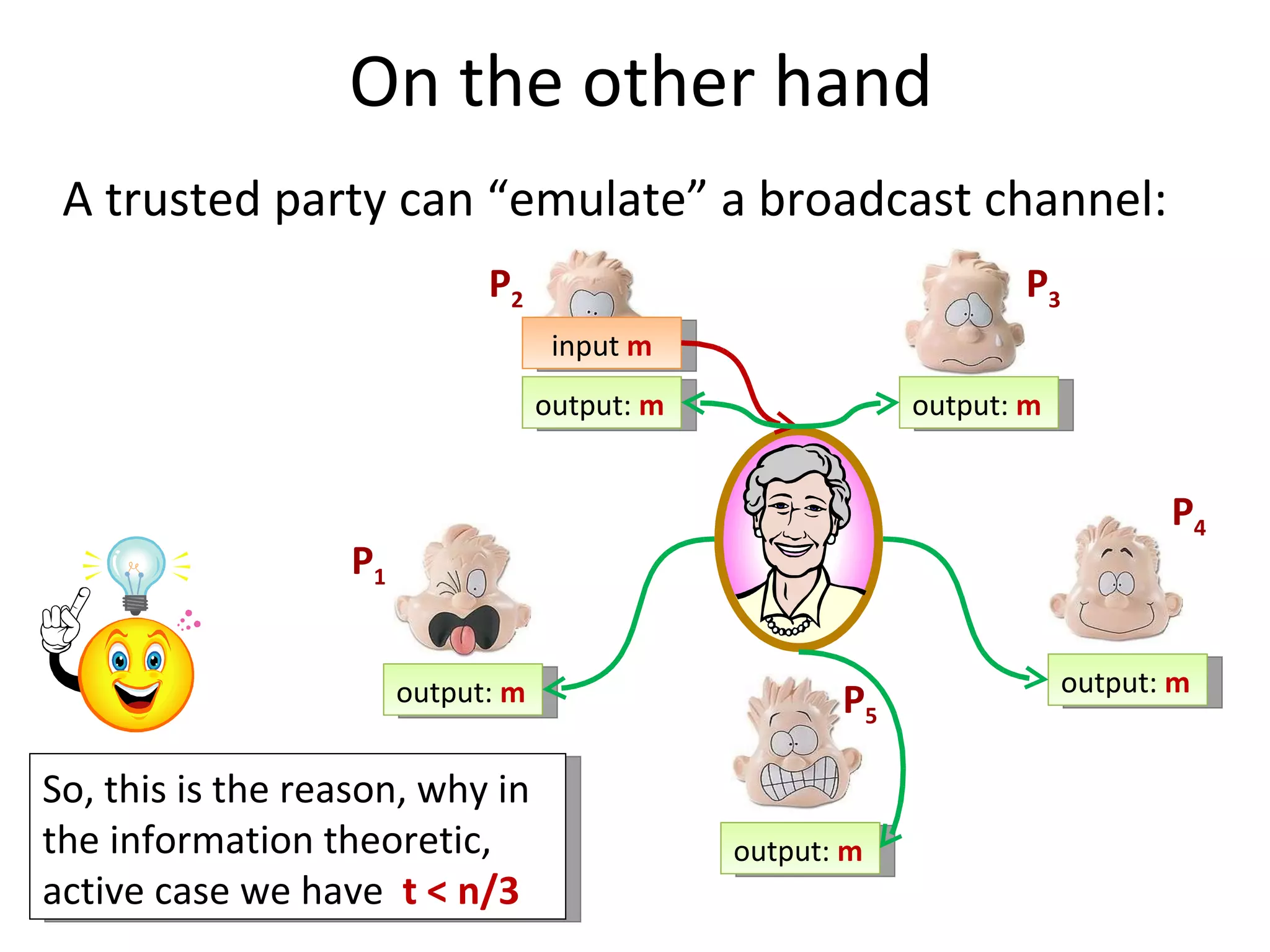

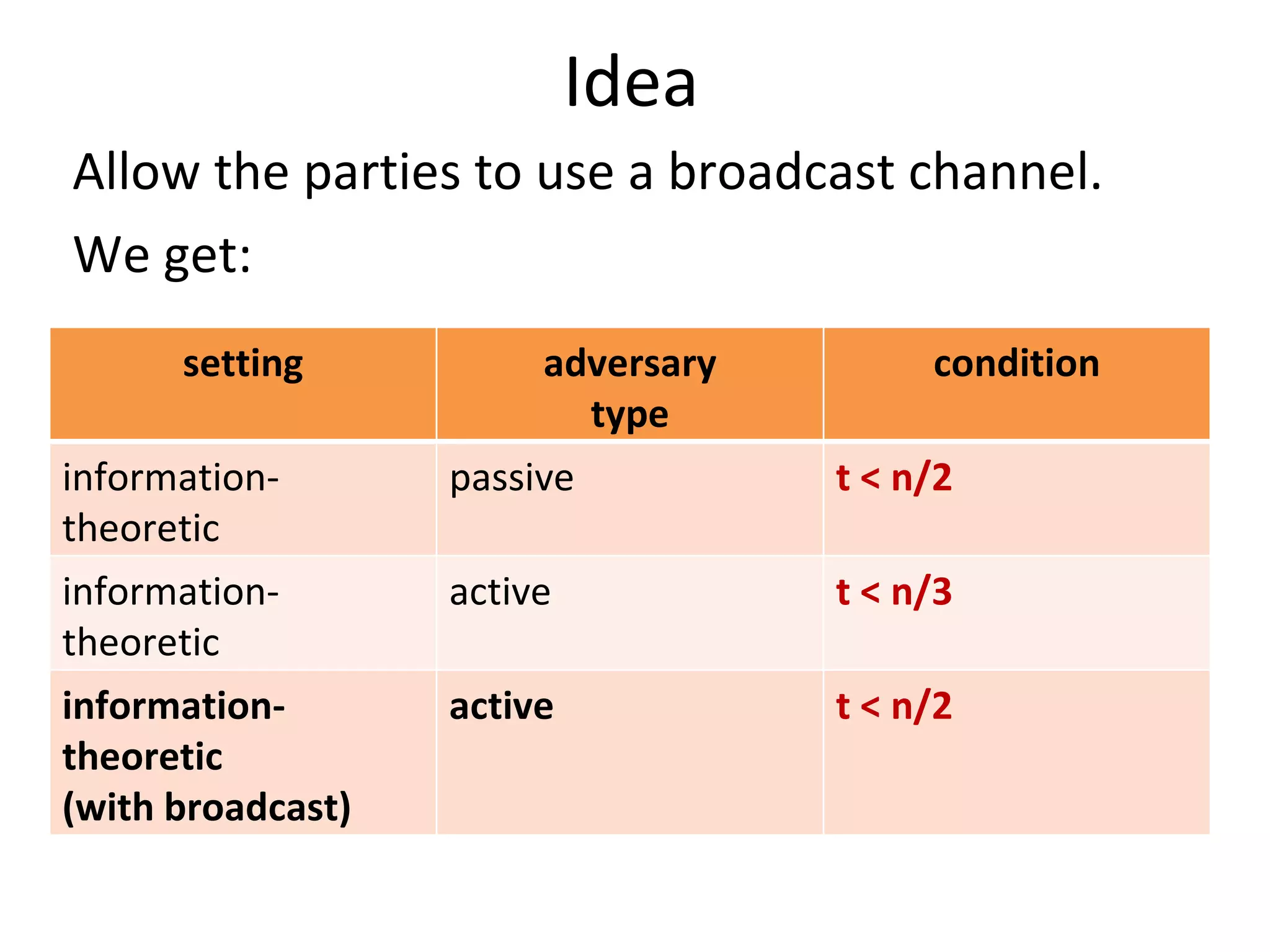

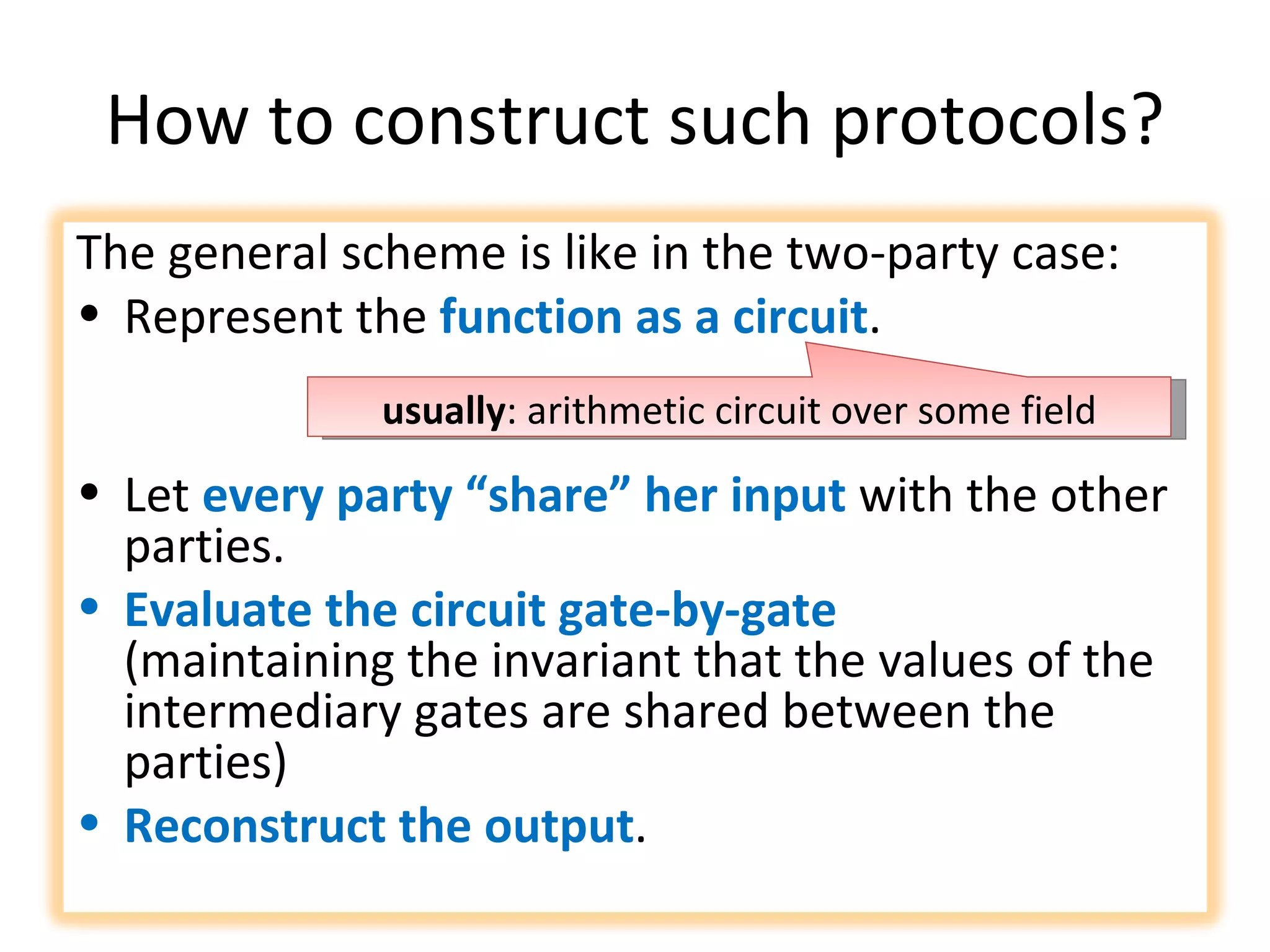

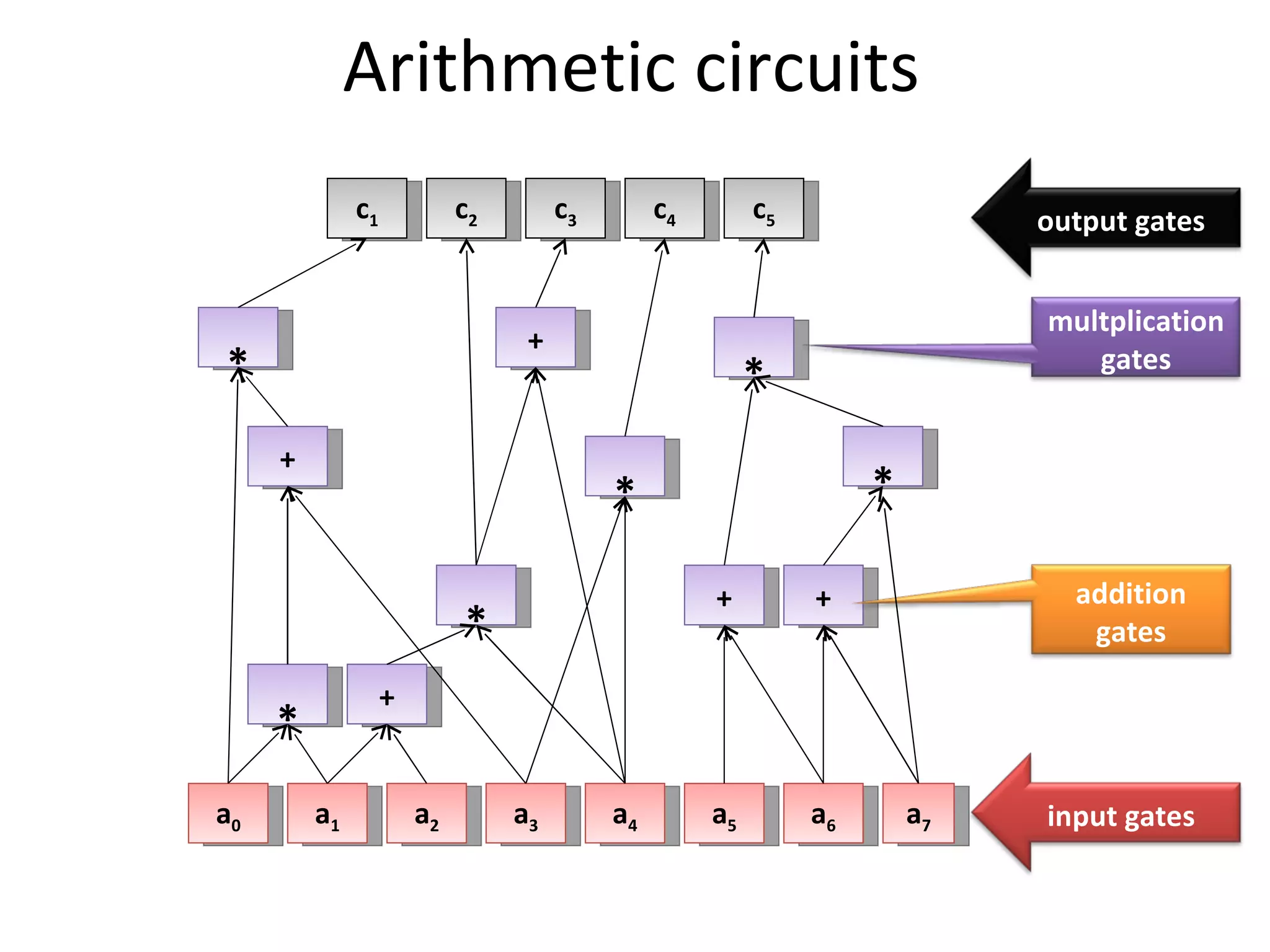

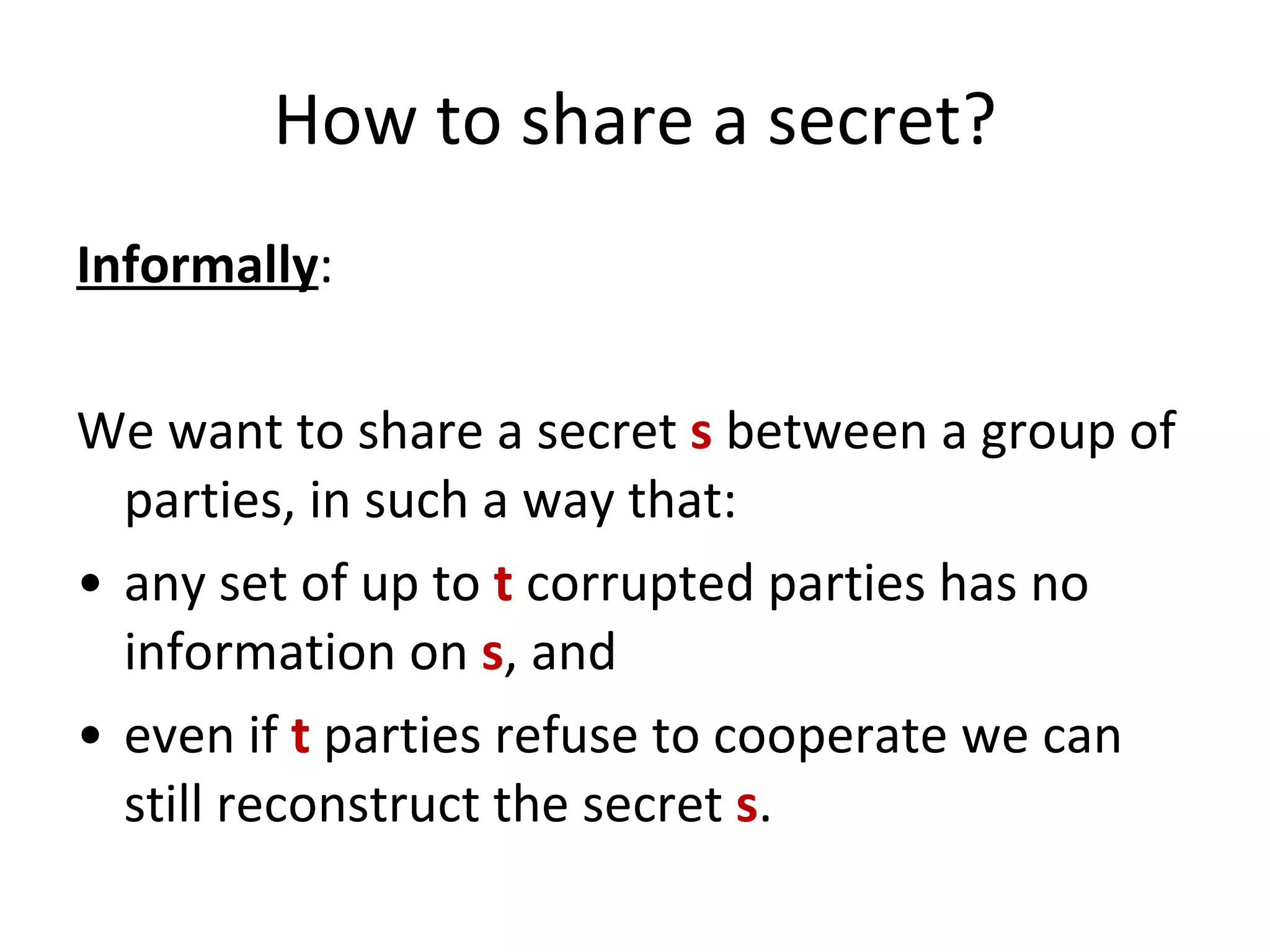

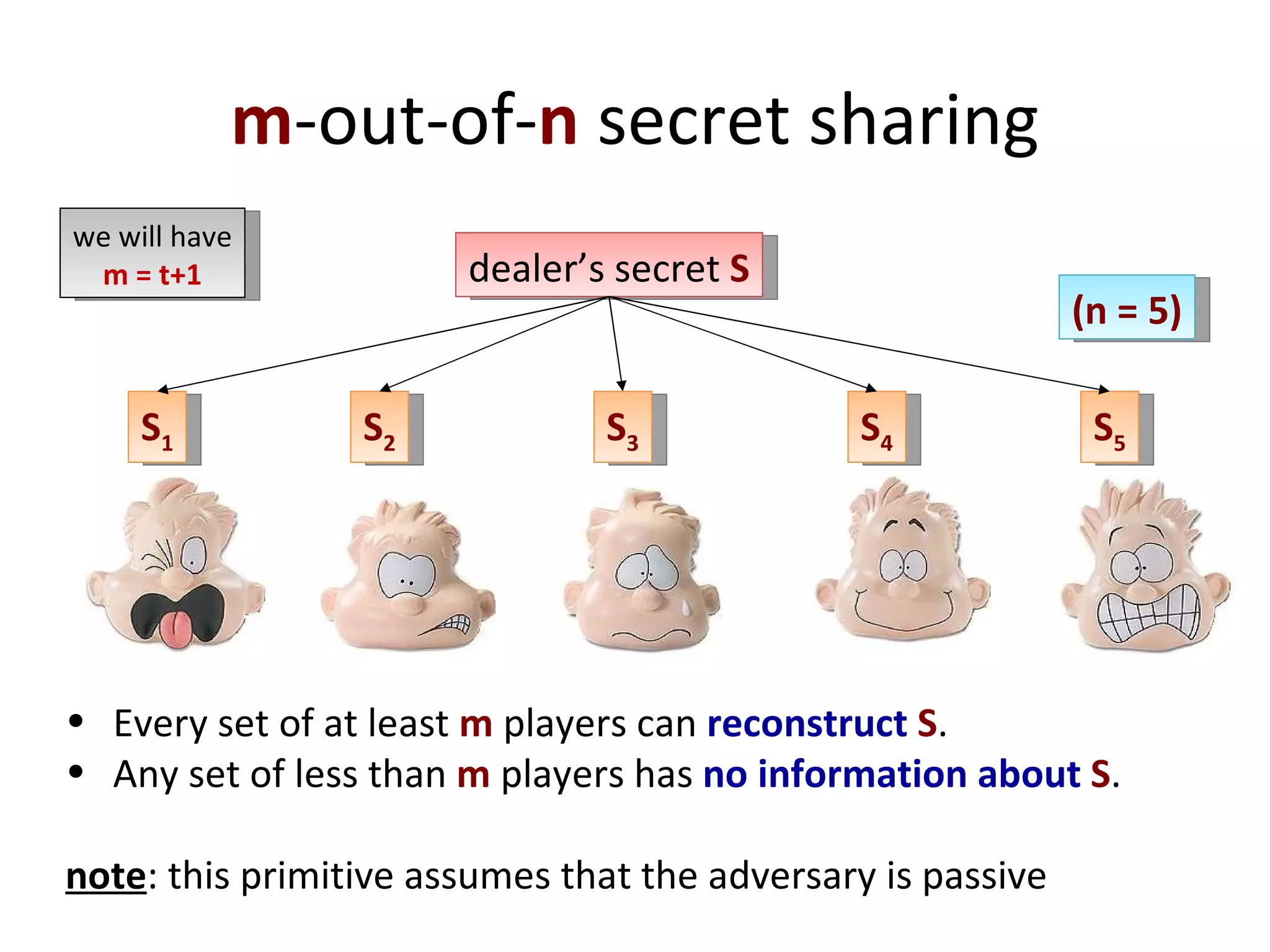

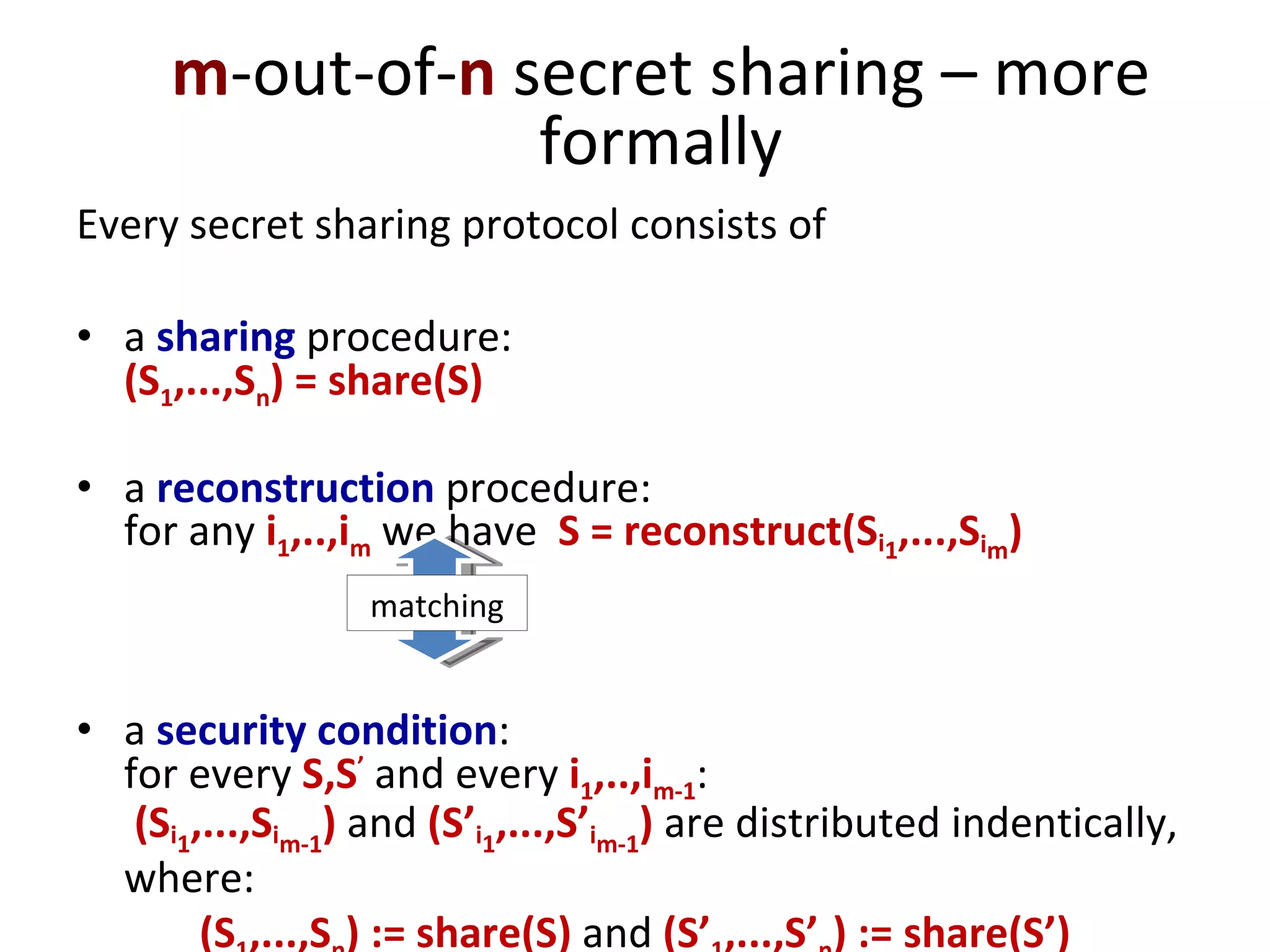

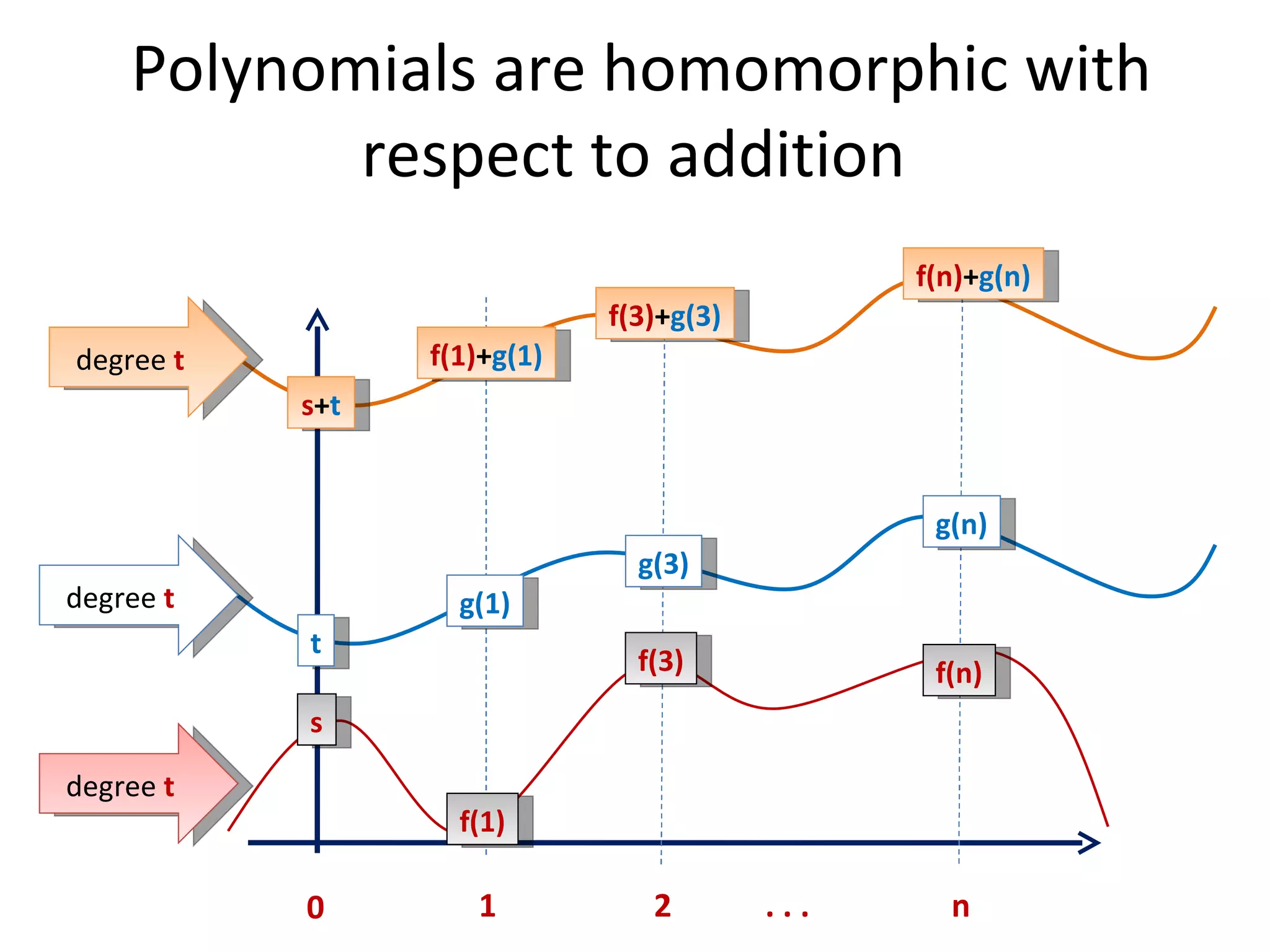

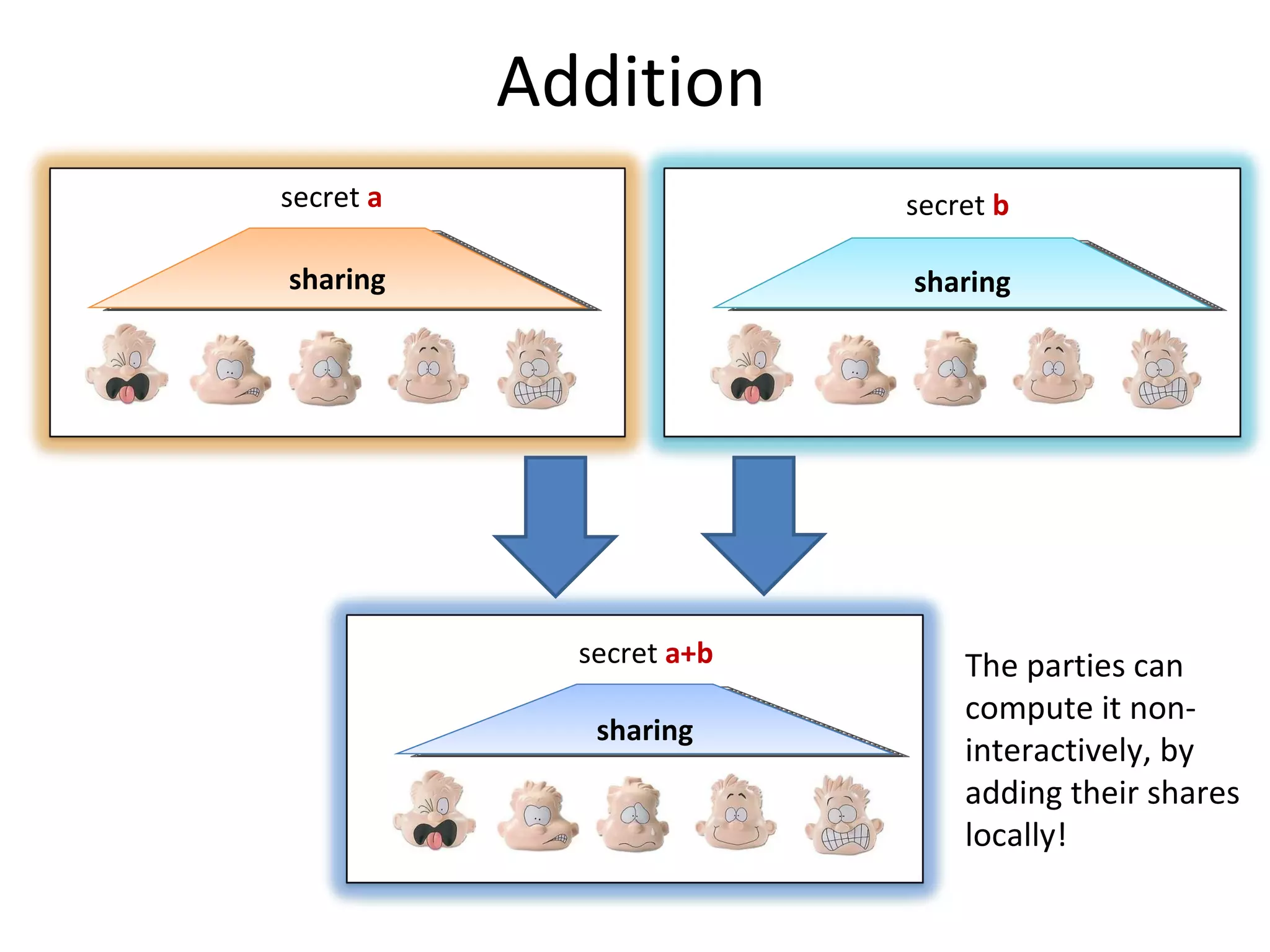

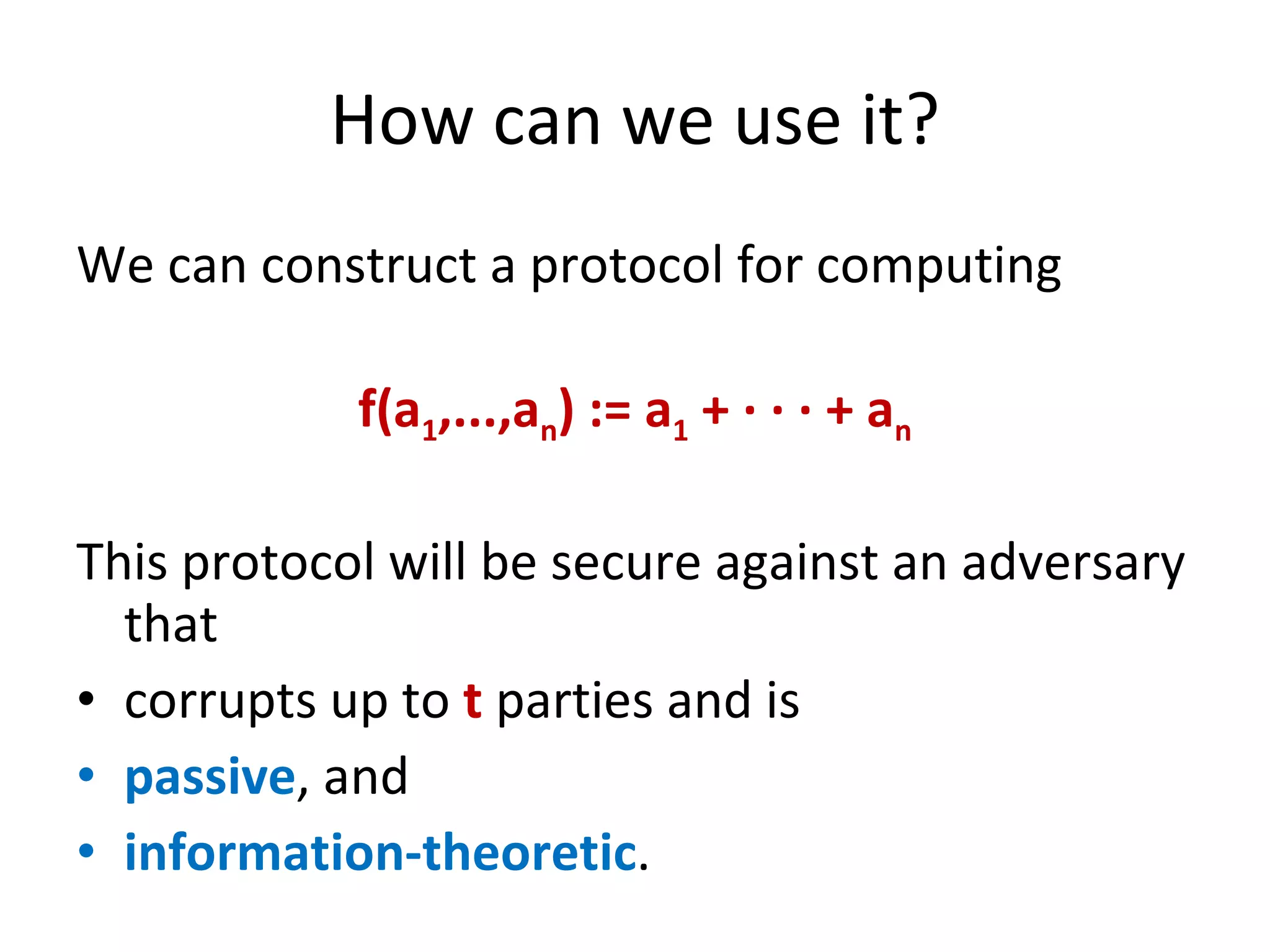

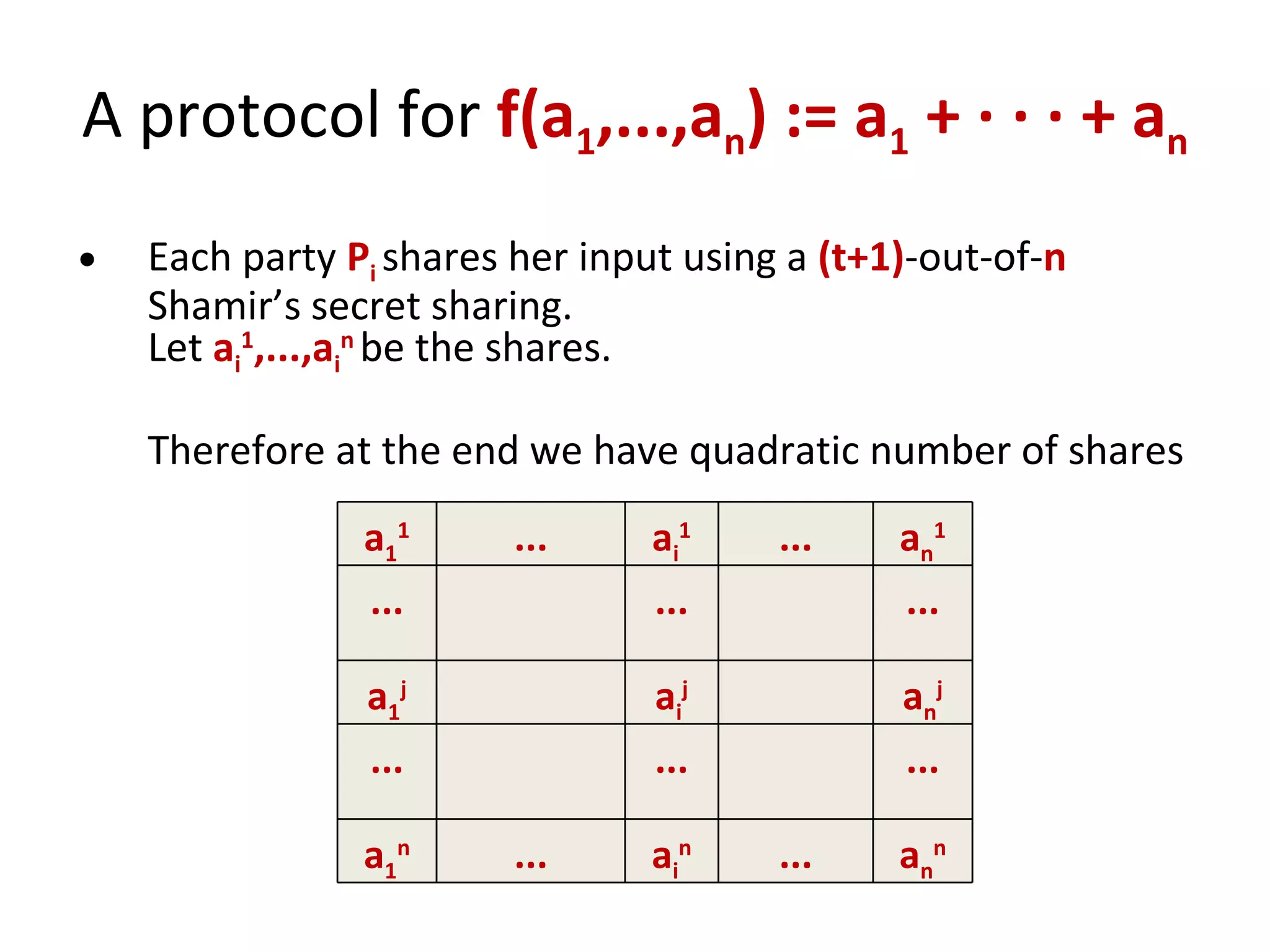

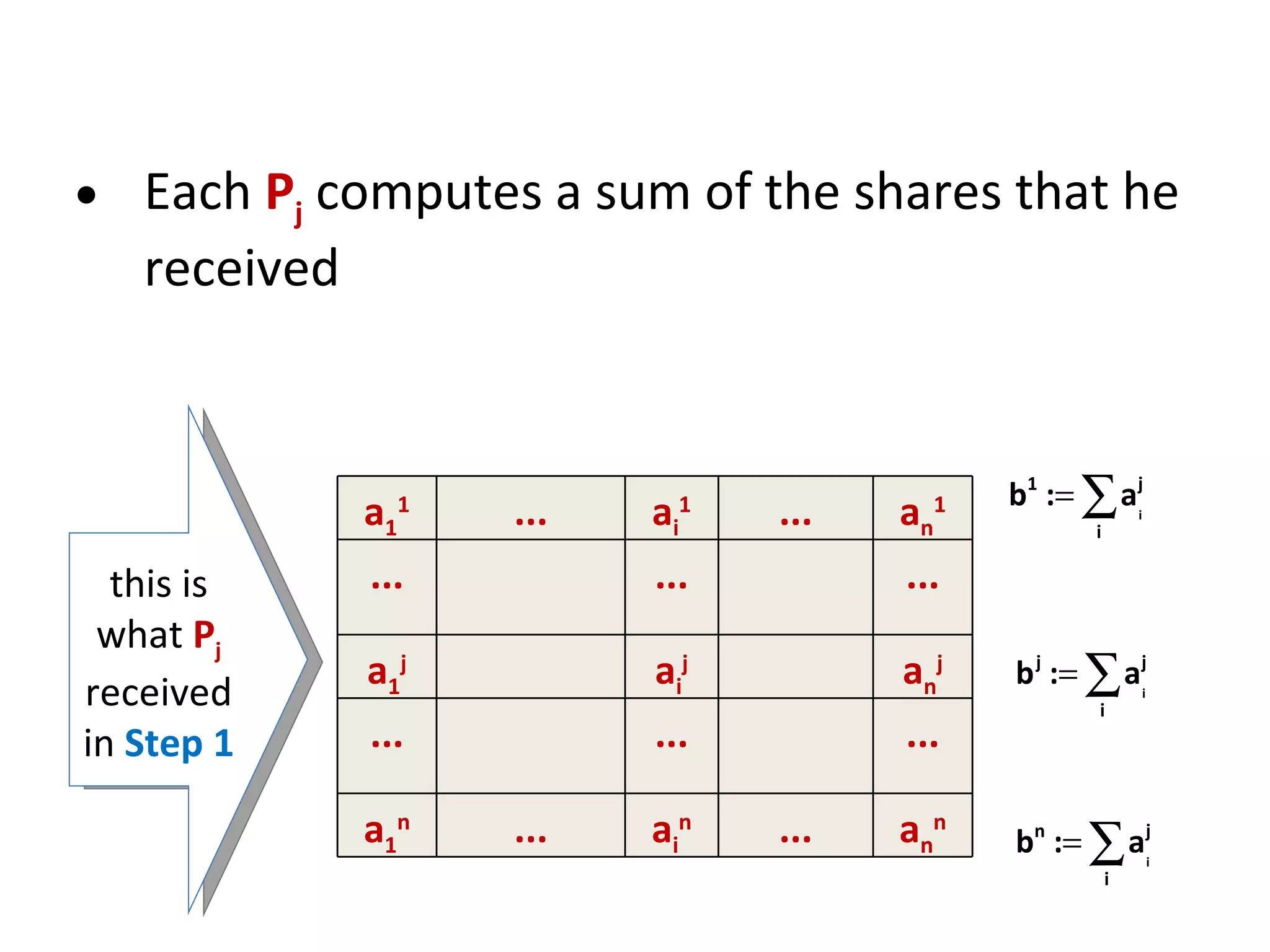

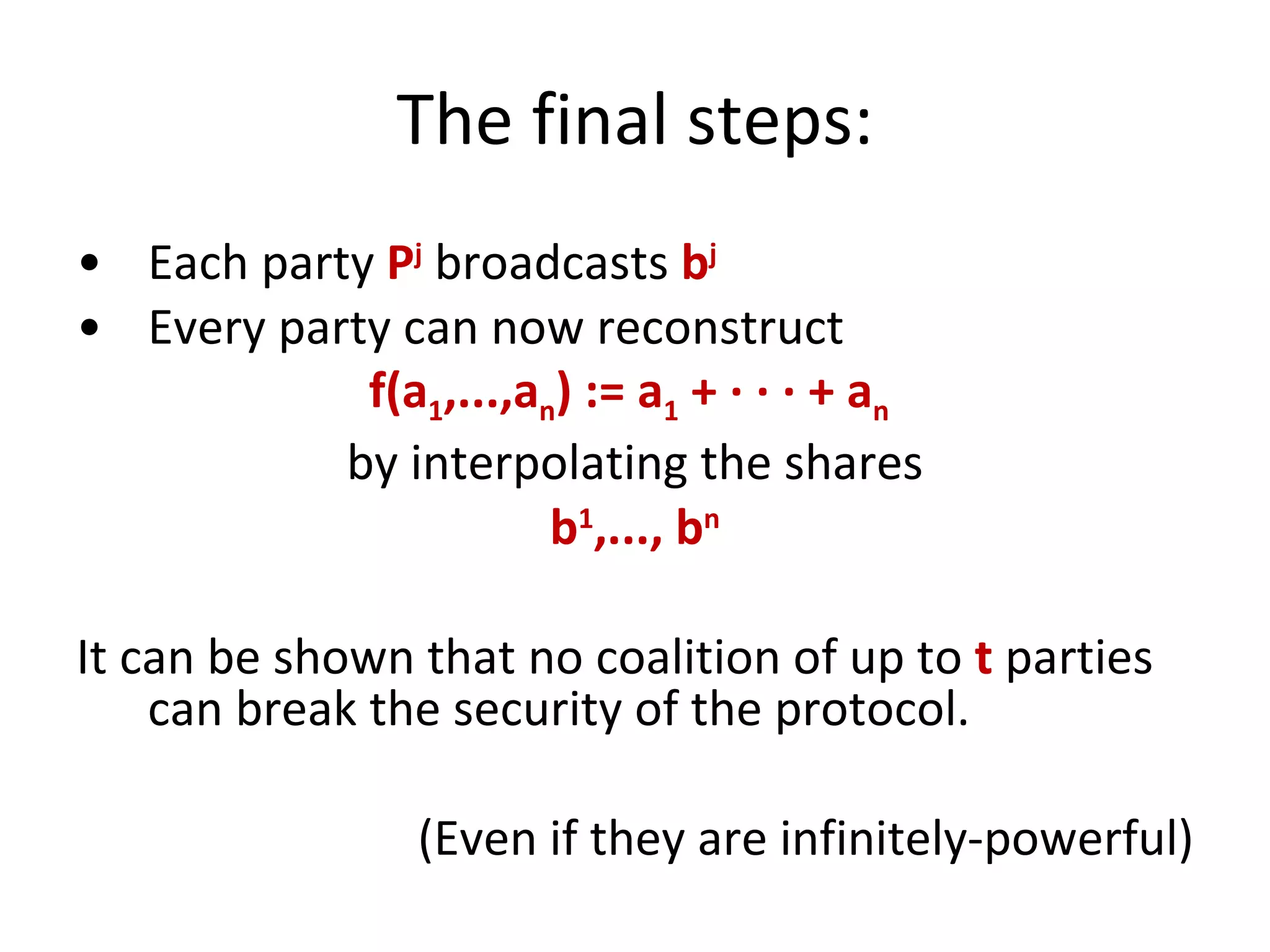

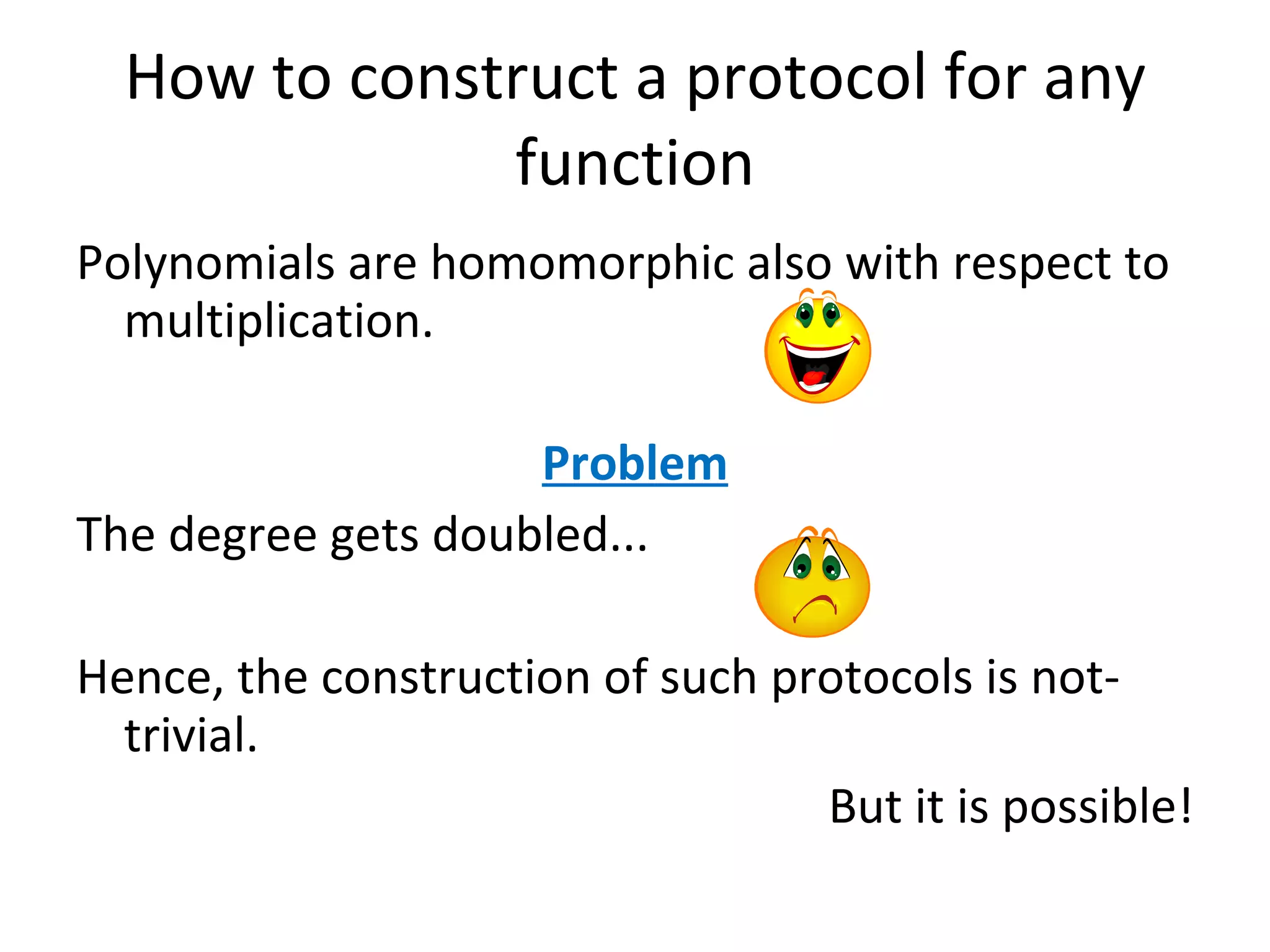

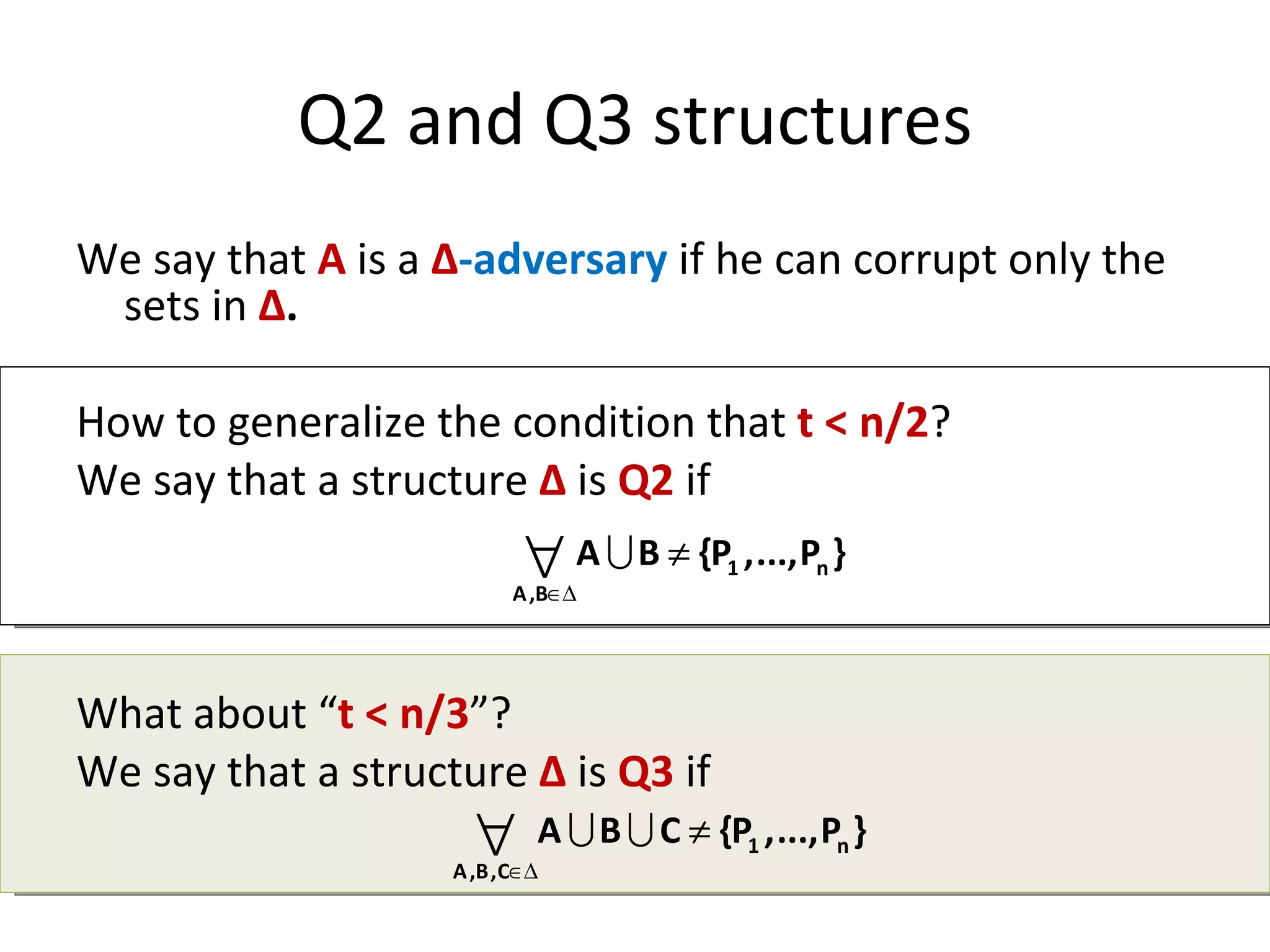

The document summarizes a lecture on multi-party computation protocols. It defines multi-party computation where multiple parties want to compute a function on their private inputs while keeping the inputs secret. It discusses security against threshold adversaries who can corrupt up to t parties. It overviews classical results on the thresholds for secure computation and constructions using secret sharing and arithmetic circuits over fields.

![Fields A field is a set F with operations + and · , and an element 0 such that F is an abelian group with the operation + , F \ {0} is an abelian group with the operation · , [distributivity of multiplication over addition] : For all a, b and c in F , the following equality holds: a · (b + c) = (a · b) + (a · c) . Examples of fields : real numbers, Z p for prime p . Polynomials over any field have many intuitive properties of the polynomials over the reals.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-10-multiparty-computation-protocols3570/75/Lecture-10-Multi-Party-Computation-Protocols-27-2048.jpg)

![Shamir’s secret sharing [1/2] 1 2 3 n . . . f(1) f(n) f(3) f(2) P 1 P 2 P 3 P n . . . s 0 Suppose that s is an element of some finite field F , such that |F| > n f – a random polynomial of degree m-1 over F such that f(0) = s sharing:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-10-multiparty-computation-protocols3570/75/Lecture-10-Multi-Party-Computation-Protocols-32-2048.jpg)

![Given f(i 1 ),...,f(i m ) one can interpolate the polynomial f in point 0 . Shamir’s secret sharing [2/2] reconstruction: security: One can show that f(i 1 ),...,f(i m-1 ) are independent on f(0) .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-10-multiparty-computation-protocols3570/75/Lecture-10-Multi-Party-Computation-Protocols-33-2048.jpg)

![A generalization of the classical results [Martin Hirt, Ueli M. Maurer: Player Simulation and General Adversary Structures in Perfect Multiparty Computation . J. Cryptology, 2000] setting adversary type condition generalized condition information-theoretic passive t < n/2 Q2 information-theoretic active t < n/3 Q3 information-theoretic with broadcast active t < n/2 Q2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-10-multiparty-computation-protocols3570/75/Lecture-10-Multi-Party-Computation-Protocols-47-2048.jpg)