Rust is a systems programming language that offers performance comparable to C and C++ with memory safety and thread safety. It uses a borrow checker to enforce rules around ownership, borrowing, and lifetimes that prevent common bugs like use of dangling pointers and data races. Rust also supports features like generics, pattern matching, and idioms that improve productivity without sacrificing performance.

![Rust is reliable

If no possible execution can exhibit undefined behaviour, we say

that a program is well-defined.

If a language’s type system enforces that every program is

well-defined, we say it is type-safe.

C/C++ are not type-safe:

char buf[16];

buf[24] = 42; // Undefined behaviour

Rust is type-safe:

Guaranteed memory-safety:

No dereference of null pointers.

No dangling pointers.

No buffer overflow.

Guaranteed thread-safety:

Threads without data races.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-6-320.jpg)

![A trivial (?) bug

1 vector<int> v;

2 v.push_back(1);

3 int& x = &v[0];

4 v.push_back(2);

5 cout << x << endl;

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-12-320.jpg)

![A trivial (?) bug

1 vector<int> v;

2 v.push_back(1);

3 int& x = &v[0];

4 v.push_back(2); // Re-allocate buffer

5 cout << x << endl;

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-13-320.jpg)

![A trivial (?) bug

1 vector<int> v;

2 v.push_back(1);

3 int& x = &v[0];

4 v.push_back(2); // Re-allocate buffer

5 cout << x << endl; // Dangling pointer!!!

segmentation fault

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-14-320.jpg)

![A trivial (?) bug

1 vector<int> v;

2 v.push_back(1);

3 int& x = &v[0];

4 v.push_back(2); // Re-allocate buffer

5 cout << x << endl; // Dangling pointer!!!

segmentation fault

Problems happen when a resource is both

aliased, i.e. there are multiple references to it;

mutable, i.e. one can modify the resource.

=⇒ restrict mutability or aliasing!

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-15-320.jpg)

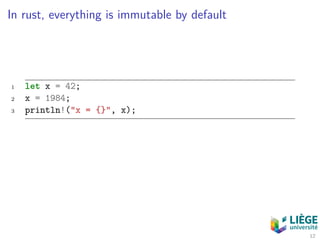

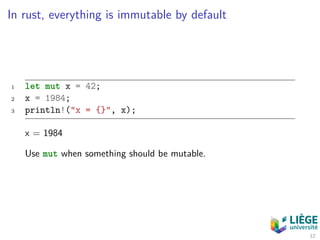

![In rust, everything is immutable by default

1 let x = 42;

2 x = 1984; // Error!

3 println!("x = {}", x);

error[E0384]: cannot assign twice to immutable variable ‘x‘

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-17-320.jpg)

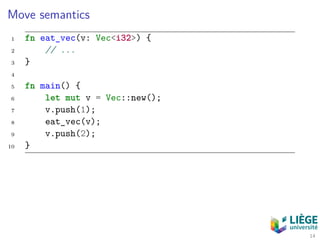

![Move semantics

1 fn eat_vec(v: Vec<i32>) {

2 // ..., then release v

3 }

4

5 fn main() {

6 let mut v = Vec::new();

7 v.push(1);

8 eat_vec(v);

9 v.push(2); // Error!

10 }

error[E0382]: use of moved value: ‘v‘

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-21-320.jpg)

![Move semantics

1 fn eat_vec(v: Vec<i32>) {

2 // ..., then release v

3 }

4

5 fn main() {

6 let mut v = Vec::new();

7 v.push(1);

8 eat_vec(v);

9 v.push(2); // Error!

10 }

error[E0382]: use of moved value: ‘v‘

Solutions:

Return value.

Copy value.

Lend value.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-22-320.jpg)

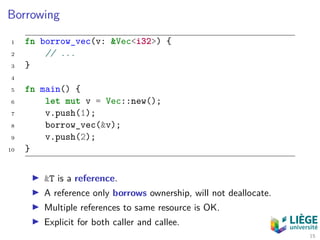

![Mutable borrow

1 fn mutate_vec(v: &mut Vec<i32>) {

2 v[0] = 42;

3 }

4

5 fn main() {

6 let mut v = Vec::new();

7 v.push(1);

8 mutate_vec(&mut v);

9 v.push(2);

10 }

&mut T is a mutable reference.

There can be only one mutable reference to a resource.

Explicit for both caller and callee.

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-24-320.jpg)

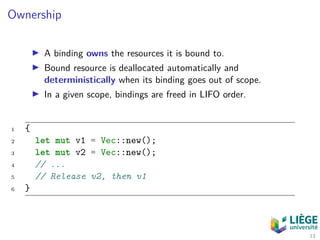

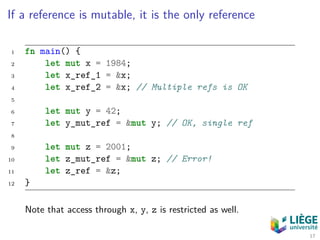

![If a reference is mutable, it is the only reference

1 fn main() {

2 let mut x = 1984;

3 let x_ref_1 = &x;

4 let x_ref_2 = &x; // Multiple refs is OK

5

6 let mut y = 42;

7 let y_mut_ref = &mut y; // OK, single ref

8

9 let mut z = 2001;

10 let z_mut_ref = &mut z; // Error!

11 let z_ref = &z;

12 }

error[E0502]: cannot borrow ‘z‘ as mutable because it is also

borrowed as immutable

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-25-320.jpg)

![Rust also tracks the lifetime of resources

2 let x;

3 { // Enter new scope

4 let y = 42;

5 x = &y; // x is a ref to y

6 } // Leave scope, destroy y

7 println!("x = {}", x); // What does x points to?

error[E0597]: `y` does not live long enough

--> test.rs:5:14

|

5 | x = &y; // x is a ref to y

| ˆ borrowed value does not live long enough

6 | } // Leave scope, destroy y

| - `y` dropped here while still borrowed

7 | println!("x = {}", x);

8 | }

| - borrowed value needs to live until here

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-27-320.jpg)

![The compiler can infer lifetimes, but sometimes needs a

little help

1 fn choose(s1: &str, s2: &str) -> &str { s1 }

2

3 fn main() {

4 let s = choose("foo", "bar");

5 println!("s = {}", s);

6 }

error[E0106]: missing lifetime specifier

help: this function’s return type contains a borrowed value, but

the signature does not say whether it is borrowed from ‘s1‘ or ‘s2‘

1 fn choose<'a>(s1: &'a str, s2: &str) -> &'a str

'static is for immortals.

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-28-320.jpg)

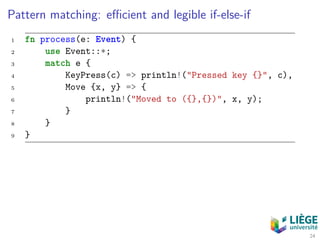

![Pattern matching: efficient and legible if-else-if

1 fn process(e: Event) {

2 use Event::*;

3 match e {

4 KeyPress(c) => println!("Pressed key {}", c),

5 Move {x, y} => {

6 println!("Moved to ({},{})", x, y);

7 }

8 }

9 }

error[E0004]: non-exhaustive patterns: ‘Click(_)‘ not covered

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-37-320.jpg)

![Pattern matching: efficient and legible if-else-if

1 fn process(e: Event) {

2 use Event::*;

3 match e {

4 KeyPress(c) => println!("Pressed key {}", c),

5 Move {x, y} => {

6 println!("Moved to ({},{})", x, y);

7 }

8 }

9 }

error[E0004]: non-exhaustive patterns: ‘Click(_)‘ not covered

Filter matches with guards: X(i) if i < 3 =>.

Combine multiple arms with One | Two =>.

Ranges: 12 .. 19 =>.

Bindings: name @ ... =>.

Partial matches with _ and ...

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-38-320.jpg)

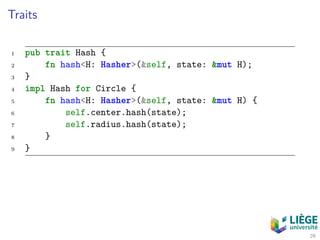

![Traits

1 pub trait Hash {

2 fn hash<H: Hasher>(&self, state: &mut H);

3 }

4 impl Hash for Circle {

5 fn hash<H: Hasher>(&self, state: &mut H) {

6 self.center.hash(state);

7 self.radius.hash(state);

8 }

9 }

Some traits support automatic implementation!

1 #[derive(PartialEq, Eq, Hash)]

2 struct Circle { /* ... */ }

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/190222cyrilsoldani-rust-190225135809/85/Le-langage-rust-46-320.jpg)