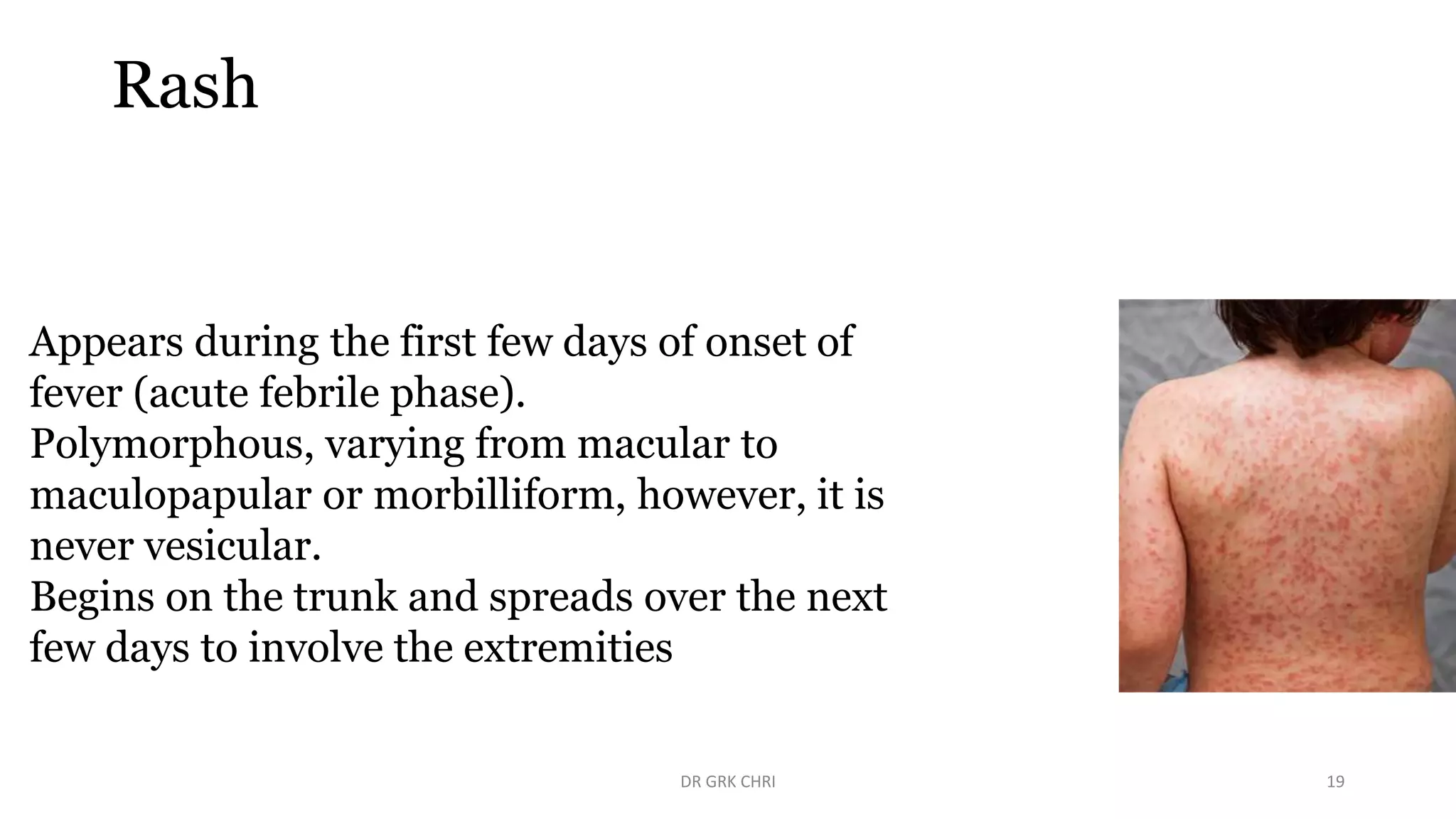

This document discusses Kawasaki disease, an acute febrile illness that commonly affects children under 5 years old. It primarily affects the blood vessels and can lead to complications like aneurysms of the coronary arteries if left untreated. The document covers the epidemiology, etiology, diagnostic criteria, clinical features and stages, differential diagnosis, investigations, and treatment of Kawasaki disease. The mainstay of treatment is intravenous immunoglobulin administered within 10 days of symptoms onset to reduce inflammation and risk of coronary complications.

![Atypical Kawasaki disease

• A child is said to have “atypical KD” when he/she presents with

clinical manifestations suggestive of KD along with some

unusual features.

• These atypical manifestations may include seizures, stroke,

nephritis, and acute hepatitis.[2,3,4] Infants may present more

commonly with atypical features and have increased

predilection for CAAs.

DR GRK CHRI 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kawasakidiseaseandhenoch-schonleinpurpurainchildren-230515063816-20521162/75/Kawasaki-Disease-and-Henoch-Schonlein-purpura-in-Children-pptx-12-2048.jpg)