Montesquieu's 'De l'esprit des lois' and the Enlightenment

- 1. Montesquieu Justice & Power, session vii

- 2. Montesquieu Justice & Power, session vii

- 3. Topics in This Session i. Introduction-The Age of the Democratic Revolution ii.Ancien Regime iii.Enlightenment iv.Montesquieu’s Education v.Montesquieu’s Career vi.De l’esprit des lois, 1748 vii.Criticism

- 4. Introduction The Age of the Democratic Revolution

- 5. Introduction The Age of the Democratic Revolution

- 6. Newton’s Principia is commonly taken to divide the first and second phases of the Scientific Revolution•. Justice & Power, p. 29

- 7. Newton’s Principia is commonly taken to divide the first and second phases of the Scientific Revolution•. Justice & Power, p. 29

- 8. Newton’s Principia is commonly taken to divide the first and second phases of the Scientific Revolution•. For a century and a half before 1687 the “new learning” had spread and gained momentum. Then, after giving birth to calculus and Newtonian mechanics, the Revolution entered a period of consolidation called the Enlightenment. The next century saw diverse and widespread attempts to apply the new theories to increase wealth, comfort, and happiness. New attention was focused on the “soft” social sciences, whereas the focus had previously been upon the “hard” physical sciences. Justice & Power, p. 29

- 9. Newton’s Principia is commonly taken to divide the first and second phases of the Scientific Revolution•. For a century and a half before 1687 the “new learning” had spread and gained momentum. Then, after giving birth to calculus and Newtonian mechanics, the Revolution entered a period of consolidation called the Enlightenment. The next century saw diverse and widespread attempts to apply the new theories to increase wealth, comfort, and happiness. New attention was focused on the “soft” social sciences, whereas the focus had previously been upon the “hard” physical sciences. Justice & Power, p. 29

- 10. In this chapter we will consider together four disparate representatives of Enlightenment thought. A major concern of this part of the course will be to see America’s foundation in the context of Western Civilization. The ideas which “[impelled us] to the separation,” natural rights, government by consent, sovereignty of the people, and separation of powers, all were perfectly familiar in Europe during the Enlightenment. As Robert Palmer• suggests...

- 11. In this chapter we will consider together four disparate representatives of Enlightenment thought. A major concern of this part of the course will be to see America’s foundation in the context of Western Civilization. The ideas which “[impelled us] to the separation,” natural rights, government by consent, sovereignty of the people, and separation of powers, all were perfectly familiar in Europe during the Enlightenment. As Robert Palmer• suggests, “the most distinctive work of the [American] Revolution was in finding a method, and furnishing a model, for putting these ideas into practical effect.” (The Age of the Democratic Revolution, vol. i, p. 214)

- 12. In this chapter we will consider together four disparate representatives of Enlightenment thought. A major concern of this part of the course will be to see America’s foundation in the context of Western Civilization. The ideas which “[impelled us] to the separation,” natural rights, government by consent, sovereignty of the people, and separation of powers, all were perfectly familiar in Europe during the Enlightenment. As Robert Palmer• suggests, “the most distinctive work of the [American] Revolution was in finding a method, and furnishing a model, for putting these ideas into practical effect.” (The Age of the Democratic Revolution, vol. i, p. 214)

- 13. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century.

- 14. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century the trickle of scepticism had become a flood. Even Spain finally had to give up burning heretics.• In one sense this “rise of modern paganism” was part of the stalemate after two centuries of religious wars. Toleration and freedom from dogmatism created deism as preferable to the type of sectarian slaughter displayed today [1977] in Lebanon, Ulster, and Uganda.• [Today, 2012, we may substitute jihad and southern Sudan as examples] How widespread the new faith in Reason was can be argued. Certainly ignorance and superstition had their disciples. But there is no denying that scientific progress did fire the imagination of many.

- 15. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century the trickle of scepticism had become a flood. Even Spain finally had to give up burning heretics.• In one sense this “rise of modern paganism” was part of the stalemate after two centuries of religious wars. Toleration and freedom from dogmatism created deism as preferable to the type of sectarian slaughter displayed today [1977] in Lebanon...

- 16. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century the trickle of scepticism had become a flood. Even Spain finally had to give up burning heretics.• In one sense this “rise of modern paganism” was part of the stalemate after two centuries of religious wars. Toleration and freedom from dogmatism created deism as preferable to the type of sectarian slaughter displayed today [1977] in Lebanon, Ulster, ....

- 17. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century the trickle of scepticism had become a flood. Even Spain finally had to give up burning heretics.• In one sense this “rise of modern paganism” was part of the stalemate after two centuries of religious wars. Toleration and freedom from dogmatism created deism as preferable to the type of sectarian slaughter displayed today [1977] in Lebanon, Ulster, ...

- 18. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century the trickle of scepticism had become a flood. Even Spain finally had to give up burning heretics.• In one sense this “rise of modern paganism” was part of the stalemate after two centuries of religious wars. Toleration and freedom from dogmatism created deism as preferable to the type of sectarian slaughter displayed today [1977] in Lebanon, Ulster, and Uganda.• [Today, 2012, we may substitute jihad and southern Sudan as examples] How widespread the new faith in Reason was can be argued. Certainly ignorance and superstition had their disciples. But there is no denying that scientific progress did fire the imagination of many.

- 19. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century the trickle of scepticism had become a flood. Even Spain finally had to give up burning heretics.• In one sense this “rise of modern paganism” was part of the stalemate after two centuries of religious wars. Toleration and freedom from dogmatism created deism as preferable to the type of sectarian slaughter displayed today [1977] in Lebanon, Ulster, and Uganda.• ...

- 20. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century the trickle of scepticism had become a flood. Even Spain finally had to give up burning heretics.• In one sense this “rise of modern paganism” was part of the stalemate after two centuries of religious wars. Toleration and freedom from dogmatism created deism as preferable to the type of sectarian slaughter displayed today [1977] in Lebanon, Ulster, and Uganda.• [Today, 2012, we may substitute jihad and southern Sudan as examples] How widespread the new faith in Reason was can be argued. Certainly ignorance and superstition had their disciples. But there is no denying that scientific progress did fire the imagination of many.

- 21. Tendencies to attack traditional authorities like Aristotle and the Church• were manifested as early as the sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century the trickle of scepticism had become a flood. Even Spain finally had to give up burning heretics.• In one sense this “rise of modern paganism” was part of the stalemate after two centuries of religious wars. Toleration and freedom from dogmatism created deism as preferable to the type of sectarian slaughter displayed today [1977] in Lebanon, Ulster, and Uganda.• [Today, 2012, we may substitute jihad and southern Sudan as examples] How widespread the new faith in Reason was can be argued. Certainly ignorance and superstition had their disciples. But there is no denying that scientific progress did fire the imagination of many.

- 22. The [famous] historian Georges Lefebvre [1874-1959] links the Enlightenment to class. The temper of the bourgeoisie...had differed since the beginning from that of the warrior or the priest….Experimental rationalism had laid the foundations of modern science and in the eighteenth century promised to embrace all man’s activity. It armed the bourgeoisie with a new philosophy which, especially in France, encouraged class consciousness and a bold inventive spirit. (The French Revolution, p. 54) This should not blind us to the fact that some of the most famous philosophes were aristocrats like Montesquieu, some self-imposed exiles from society like Rousseau, natural aristocrats like Jefferson, or gentry like Burke.

- 23. The [famous] historian Georges Lefebvre [1874-1959]• links the Enlightenment to class. The temper of the bourgeoisie...had differed since the beginning from that of the warrior or the priest….Experimental rationalism had laid the foundations of modern science and in the eighteenth century promised to embrace all man’s activity. It armed the bourgeoisie with a new philosophy which, especially in France, encouraged class consciousness and a bold inventive spirit. (The French Revolution, p. 54)• This should not blind us to the fact that some of the most famous philosophes were aristocrats like Montesquieu, ...

- 24. The [famous] historian Georges Lefebvre [1874-1959]• links the Enlightenment to class. The temper of the bourgeoisie...had differed since the beginning from that of the warrior or the priest….Experimental rationalism had laid the foundations of modern science and in the eighteenth century promised to embrace all man’s activity. It armed the bourgeoisie with a new philosophy which, especially in France, encouraged class consciousness and a bold inventive spirit. (The French Revolution, p. 54)• This should not blind us to the fact that some of the most famous philosophes were aristocrats like Montesquieu, some self-imposed exiles from society like Rousseau, ...

- 25. The [famous] historian Georges Lefebvre [1874-1959]• links the Enlightenment to class. The temper of the bourgeoisie...had differed since the beginning from that of the warrior or the priest….Experimental rationalism had laid the foundations of modern science and in the eighteenth century promised to embrace all man’s activity. It armed the bourgeoisie with a new philosophy which, especially in France, encouraged class consciousness and a bold inventive spirit. (The French Revolution, p. 54)• This should not blind us to the fact that some of the most famous philosophes were aristocrats like Montesquieu, some self-imposed exiles from society like Rousseau, natural aristocrats like Jefferson, or gentry...

- 26. The [famous] historian Georges Lefebvre [1874-1959]• links the Enlightenment to class. The temper of the bourgeoisie...had differed since the beginning from that of the warrior or the priest….Experimental rationalism had laid the foundations of modern science and in the eighteenth century promised to embrace all man’s activity. It armed the bourgeoisie with a new philosophy which, especially in France, encouraged class consciousness and a bold inventive spirit. (The French Revolution, p. 54)• This should not blind us to the fact that some of the most famous philosophes were aristocrats like Montesquieu•, some self-imposed exiles from society like Rousseau•, natural aristocrats like Jefferson, or gentry like Burke.

- 27. Enlightenment thought on the nature of the state was broad enough to include organic theorists like Montesquieu and Burke ...

- 28. Enlightenment thought on the nature of the state was broad enough to include organic theorists like Montesquieu and Burke and also instrumentalists...

- 29. Enlightenment thought on the nature of the state was broad enough to include organic theorists like Montesquieu and Burke and also instrumentalists like Jefferson and Rousseau...

- 30. Enlightenment thought on the nature of the state was broad enough to include organic theorists like Montesquieu and Burke and also instrumentalists like Jefferson and Rousseau. The degree of bitterness with which critics denounced the status quo varied widely also. Montesquieu and Burke were basically enlightened aristocratic reformers who believed that popular sovereignty was a dangerous seducement.

- 31. Enlightenment thought on the nature of the state was broad enough to include organic theorists like Montesquieu and Burke and also instrumentalists like Jefferson and Rousseau•. The degree of bitterness with which critics denounced the status quo varied widely also. Montesquieu and Burke• were basically enlightened aristocratic reformers who believed that popular sovereignty was a dangerous seducement. Rousseau and Jefferson would not settle for half a revolutionary loaf..

- 32. Enlightenment thought on the nature of the state was broad enough to include organic theorists like Montesquieu and Burke and also instrumentalists like Jefferson and Rousseau. The degree of bitterness with which critics denounced the status quo varied widely also. Montesquieu and Burke were basically enlightened aristocratic reformers who believed that popular sovereignty was a dangerous seducement. Rousseau and Jefferson would not settle for half a revolutionary loaf. When we apply the criteria of optimism, faith in progress, and the perfectibility of man, we find different pairs. Jefferson and Montesquieu looked to the future with the greatest confidence.

- 33. Enlightenment thought on the nature of the state was broad enough to include organic theorists like Montesquieu and Burke and also instrumentalists like Jefferson and Rousseau. The degree of bitterness with which critics denounced the status quo varied widely also. Montesquieu and Burke were basically enlightened aristocratic reformers who believed that popular sovereignty was a dangerous seducement. Rousseau and Jefferson would not settle for half a revolutionary loaf. When we apply the criteria of optimism, faith in progress, and the perfectibility of man, we find different pairs. Jefferson and Montesquieu looked to the future with the greatest confidence. Burke and Rousseau both suspected conventional notions of progress.

- 34. By the end of the eighteenth century events forced men to choose. Men either sided with Rousseau and Jefferson in sharing “...a new feeling for a kind of equality, or at least a discomfort with older forms of social stratification” in Palmer’s succinct description of the Democratic Revolution’s core. (Democratic Revolution, p. 4). Or, men recoiled from the forces which events had called forth and sought conservative checks on the power unleashed from the depths of society.

- 35. As you review the history and read the excerpts from this decisive period, remember that the issues which these men argued are not closed, not settled once and for all. When Franklin was leaving the Philadelphia Convention in September, 1787...

- 37. As you review the history and read the excerpts from this decisive period, remember that the issues which these men argued are not closed, not settled once and for all. When Franklin was leaving the Philadelphia Convention in September, 1787, a lady asked him what form of government they had settled upon behind closed doors. The answer was “A Republic, Madam, if you can keep it.” As the Greeks knew only too well, democracy has a habit of giving way to tyranny.

- 38. Ancien Regime

- 39. Ancien Regime

- 40. II. Ancien Regime A. aristocracy B. Huguenots 1. Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, 1695 2. anti-clericalism 3. ecrasez l’enfame- Voltaire

- 41. “...gilded butterflies…”--King Lear, v, 3

- 42. nobles vs aristocrats In 18th century France both these terms were used for the Second Estate But by this time many distinctions had developed within the group which constituted perhaps the top 1.5- 2 % of the 24-28 million citizens of France. The newer term, aristocrat, implied not only noble birth but also “liberal education, refined manners, punctilious courtesy and the nicest sense of personal honor” (John Paul Jones’ definition of a naval officer). T broad divisions wo existed: noblesse d’épée (...of the sword) and ...de robe (the lawyers ennobled as judges). Montesquieu’s family qualified under both.The range of personal wealth varied greatly. Some of the poorest, called hobireaux, were less well off than some peasant proprietors! It was said the the king could create a noble with the touch of his sword but that it took three generations to create an aristocrat. Again, Montesquieu qualified under both definitions. jbp

- 43. II.B. Huguenots-French Protestants 1. Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, 1695. “Good King”Henri iv had granted the Huguenots limited religious toleration in this edict in 1598•. Louis xiv felt strong enough to revoke it. As late as the 1780s Protestant clergy were condemned to row in the galleys of Toulon

- 44. II.B. Huguenots-French Protestants The original edict of 1598 which had guaranteed limited religious freedom

- 45. II.B. Huguenots-French Protestants 1. Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, 1695. “Good King”Henri iv had granted the Huguenots limited religious toleration in this edict in 1598•. Louis xiv felt strong enough to revoke it. As late as the 1780s Protestant clergy were condemned to row in the galleys of Toulon 2. As the Enlightenment began to sway the literate upper classes, a wave of hostility towards the Church and its privileged position turned into anti- clericalism

- 46. II.B. Huguenots-French Protestants 1. Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, 1695. “Good King”Henri iv had granted the Huguenots limited religious toleration in this edict in 1598•. Louis xiv felt strong enough to revoke it. As late as the 1780s Protestant clergy were condemned to row in the galleys of Toulon 2. As the Enlightenment began to sway the literate upper classes, a wave of hostility towards the Church and its privileged position turned into anti- clericalism 3. most famous was Voltaire’s "écrasez l'infâme", or "crush the infamous". The phrase refers to abuses of the people by royalty and the clergy that Voltaire saw around him, and the superstition and intolerance that the clergy bred within the people.”--Wikipedia

- 47. Enlightenment A Philosopher giving a Lecture on the Orrery in which a lamp is put in place of the Sun painting by Joseph Wright of Derby, ca 1766

- 48. A Philosopher giving a Lecture on the Orrery in which a lamp is put in place of the Sun painting by Joseph Wright of Derby, ca 1766

- 49. III. Enlightenment - l’ eclairement A. Pope’s couplet B. applications 1. clocks 2. industrial revolution 3. social science C. Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedie, 1751-72 1. contributors 2. themes a. philosophy b. theology c. social theory d. political theory

- 50. III.A.-Pope’s couplet "Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night; God said, Let Newton be! and all was light."

- 51. III.A.-Pope’s couplet "Nature and Nature's laws lay hid in night; God said, Let Newton be! and all was light." "Let there be light" is an English translation of the Hebrew ( יְהִי אֹורyehiy 'or). Other translations of the same phrase include the Latin phrase fiat lux, and the Greek phrase γενηθήτω φῶς (or genēthētō phōs). The phrase is often used for its metaphorical meaning of dispelling ignorance. The phrase comes from the third verse of the Book of Genesis. In the King James Bible, it reads, in context: 1:1 - In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. 1:2 - And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. 1:3 - And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. 1:4 - And God saw the light, and it was good; and God divided the light from the darkness. Wikipedia

- 52. III.A.-Pope’s couplet The phrase "Let there be light" used metaphorically over the door of a Carnegie library, in Edinburgh

- 53. hence, the Enlightenment Aufklärung, Ger. = cf., clarification, clearing up éclairement, Fr. просвещение, (pros•vesh•CHENIE)Russ. = from CBET, “light,” a “bringing to light”

- 54. III.B. Applications 1. clocks 1. A major stimulus to improving the accuracy and reliability of clocks was the importance of precise time- keeping for navigation. The position of a ship at sea could be determined with reasonable accuracy if a navigator could refer to a clock that lost or gained less than about 10 seconds per day. This clock could not contain a pendulum, which would be virtually useless on a rocking ship. Many European governments offered a large prize for anyone who could determine longitude accurately; for example, Great Britain offered 20,000 pounds, equivalent to millions of dollars today. The reward was eventually claimed in 1761 by John Harrison, who dedicated his life to improving the accuracy of his clocks. His H5 clock was in error by less than 5 seconds over 10 weeks.

- 56. 18th century exploring the globe-greatly aided by chronometers, better chart-making & navigation Vitus Bering (1681-1741) Danish explorer who explored Siberia and Alaska for Russia Carl Linnaeus (1708-1778)- Swedish biologist. his six-month expedition to Lapland in 1732 described about 100 previously unknown plants Juan José Pérez Hernández (1725-1775) Spanish explorer, the first to chart the American Pacific Northwest James Cook (1728-1779) British naval commander. Explored much of the Pacific including New Zealand, Australia and Hawaii Alexander MacKenzie (1764-1820) Scottish-Canadian explorer who in 1789, looking for the Northwest Passage, followed the river now named for him to the Arctic Ocean and then in 1793 crossed the Rockies and reached the Pacific, thus beating Lewis and Clark by 12 years

- 57. 18th century exploring the globe-greatly aided by chronometers, better chart-making & navigation Vitus Bering (1681-1741) Danish explorer who explored Siberia and Alaska for Russia Carl Linnaeus (1708-1778)- Swedish biologist. his six-month expedition to Lapland in 1732 described about 100 previously unknown plants Juan José Pérez Hernández (1725-1775) Spanish explorer, the first to chart the American Pacific Northwest James Cook (1728-1779) British naval commander. Explored much of the Pacific including New Zealand, Australia and Hawaii Alexander MacKenzie (1764-1820) Scottish-Canadian explorer who in 1789, looking for the Northwest Passage, followed the river now named for him to the Arctic Ocean and then in 1793 crossed the Rockies and reached the Pacific, thus beating Lewis and Clark by 12 years A general map of the world by Samuel Dunn, 1794

- 58. III.B. Applications 1. clocks 2.industrial revolution 1. not simply a story of machinery

- 59. III.B. Applications 1. clocks 2.industrial revolution 1. not simply a story of machinery Watt’s steam engine, 1763-1775

- 60. III.B. Applications 1. clocks 2.industrial revolution 1. not simply a story of machinery Watt’s steam engine, 1763-1775 2. an Agricultural Revolution freed up cheap urban labor 3. the revolution began in Britain, where there was a special case of Enlightenment-based advantages: 1. peace, stability & no trade barriers after the 1708 unification of England & Scotland 2. rule of law permitting sanctity of contracts and joint-stock contracts 3. infrastructure of canals & coastal shipping 4. new energy sources (water & coal--> steam) replaced human and animal power 5. an established textile industry which satisfied “man’s second basic need”

- 61. III.B. Applications 1. clocks 2.industrial revolution 3. social science 1. Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794) his reading of Montesquieu led him to the field of penology 2. His “On Crimes and Punishments” (1764)

- 62. III.B. Applications 1. clocks 2.industrial revolution 3. social science 1. Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794) his reading of Montesquieu led him to the field of penology 2. His “On Crimes and Punishments” (1764) 1. punishment had a deterrent, as well as a retributive, function 2. punishment should be proportionate to the crime 3. the certainty of punishment, not its severity, would achieve the preventive effect 4. procedures should be public 5. in order to be effective, punishment must be prompt

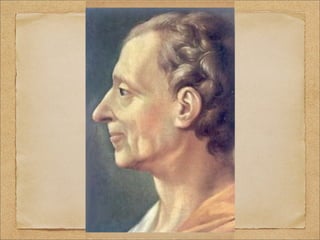

- 64. Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu 1689 – 1755

- 65. IV. Montesquieu’s Education A. classics 1. Stoicism B. law - social determinism 1. parlement of Bordeaux, 1716-26 a. quasi-executive b. quasi-judicial

- 66. IV.A.-classics 1. Stoicism Marcus Aurelius, the Stoic Emperor, 121-180 A.D.

- 67. IV.A.-classics 1. Stoicism Philosophy for a Stoic is not just a set of beliefs or ethical claims, it is a way of life involving constant practice and training or askesis. Stoic philosophical and spiritual practices included logic, Socratic dialog and self-dialog, contemplation of death, training attention to remain in the present moment (similar to some forms of Eastern meditation), daily reflection on everyday problems and possible solutions, hypomnemata*, and so on. Philosophy for a Stoic is an active process of constant practice and self-reminder. In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius defines several such practices. For example, in Book II, part 1: Say to yourself in the early morning: I shall meet today ungrateful, violent, treacherous, envious, uncharitable men. All of these things have come upon them through ignorance of real good and ill... I can neither be harmed by any of them, for no man will involve me in wrong, nor can I be angry with my kinsman or hate him; for we have come into the world to work together… Wikipedia * written notes to “remember” important thoughts

- 68. IV.B.-law-social determinism 1. Parlement of Bordeaux, 1716-1726 He was born [in 1689] at the Château de la Brède in the southwest of France. Wikipedia

- 70. IV.B.-law-social determinism 1. Parlement of Bordeaux, 1716-1726 He was born [in 1689] at the Château de la Brède• in the southwest of France. His father, Jacques de Secondat, was a soldier with a long noble ancestry. His mother, Marie Françoise de Pesnel who died when Charles de Secondat was seven, was a female inheritor of a large monetary inheritance who brought the title of barony of La Brède to the Secondat family. After having studied at the Catholic College of Juilly, Charles-Louis de Secondat married. His wife, Jeanne de Lartigue, a Protestant, brought him a substantial dowry when he was 26. The next year, he inherited a fortune upon the death of his uncle, as well as the title Baron de Montesquieu and Président à Mortier in the Parliament of Bordeaux•. Wikipedia La Brède

- 71. IV.B.-law-social determinism 1. Parlement of Bordeaux, 1716-1726 He was born [in 1689] at the Château de la Brède in the southwest of France. His father, Jacques de Secondat, was a soldier with a long noble ancestry. His mother, Marie Françoise de Pesnel who died when Charles de Secondat was seven, was a female inheritor of a large monetary inheritance who brought the title of barony of La Brède to the Secondat family. After having studied at the Catholic College of Juilly, Charles-Louis de Secondat married. His wife, Jeanne de Lartigue, a Protestant, brought him a substantial dowry when he was 26. The next year, he inherited a fortune upon the death of his uncle, as well as the title Baron de Montesquieu and Président à Mortier in the Parliament of Bordeaux. Wikipedia

- 72. IV.B.-law-social determinism 1. Parlement of Bordeaux, 1716-1726 a. quasi-executive b. quasi-judicial Bordeaux

- 73. IV.B.-law-social determinism 1. Parlement of Bordeaux, 1716-1726 a. quasi-executive b. quasi-judicial Parlement were a medieval body controlled by the French nobility which, by the 18th century, were local arms of the royal power. They supervised the king’s orders to the local regions of France and also served as courts in certain cases. jbp

- 74. Montesquieu’s Career

- 75. Montesquieu’s Career A 19th century picture of the French Academy

- 76. V. Montesquieu’s Career 1. “man of letters” 2. salon society 3. Persian Letters, 1721 4. L'Académie française 1726-no, 1728-yes 5. travels in England, 1729-31 a. Lord Chesterfield b. Royal Society c. Voltaire’s experience 6. Considerations on the Greatness and Decline of Rome, 1734

- 77. V.1- “man of letters” Men of letters The term "Man of Letters" ("belletrist", from the French belles-lettres), has been used in some Western cultures to denote contemporary intellectual men; the term rarely denotes "scholars", and is not synonymous with "academic". Originally the term implied a distinction between the literate and the illiterate, which carried great weight when literacy was rare. It also denoted the literati (Latin, plural of literatus), the "citizens of the Republic of Letters" in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France, where it evolved into the salon, usually run by women.” Wikipedia

- 79. V.2 -salon society Voltaire Anciet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier (1743-1824): Madame Geo!in's salon in 1755, painted in 1812

- 80. V.3 - Persian Letters, 1721 at age 32, he became a European celebrity with this bombshell, published anonymously in Geneva “Through the letters of two imaginary Persian visitors to Paris, he showed the reactions of unprejudiced observers to the irrationalities and imperfections of the western world “...the device enabled him to comment on taboos that would otherwise be too delicate to handle [its sexual content added to its popularity] “[he] satirized the Roman Catholic Church … “...the pope is described as a magician who makes believe ‘that three are one, that the bread one eats is not bread…’ “the clergy…’a society of persons who always take, and never give.’ “--Ebenstein, p. 415

- 81. V.4-L'Académie française In 1726 Montesquieu was proposed--at an unusually early age [37]--for membership in the French Academy, but king Louis XV objected. In 1728 he was able to win entry into the ranks of the “immortals” in French letters. During that same year he set out on his travels, which took him to Austria, Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland; from Holland, in the fall of 1729, he went to England, where he stayed until the spring of 1731. Ebenstein, p.p. 415-416

- 82. V.5 - Travels in England, 1729-1731 a. Montesquieu was the house guest of this famous luminary of the British Enlightenment. They had met in the Netherlands where Lord Chesterfield had been the British ambassador Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, PC, KG 1694 – 1773 a British statesman and man of letters

- 83. V.5.a.- Lord Chesterfield Among the quotations attributed to him are: • "The world is a country which nobody ever yet knew by description; one must travel through it one's self to be acquainted with it." • "An able man shows his spirit by gentle words and resolute actions." • "I recommend you to take care of the minutes, for the hours will take care of themselves." • "Firmness of purpose is one of the most necessary sinews of character, and one of the best instruments of success. Without it, genius wastes its efforts in a maze of inconsistencies." • "The scholar, without good breeding, is a pedant; the philosopher, a cynic; the soldier, a brute; and every man disagreeable." Wikipedia

- 84. V.5 - Travels in England, 1729-1731 a. Montesquieu was the house guest of this famous luminary of the British Enlightenment. They had met in the Netherlands where Lord Chesterfield had been the British ambassador b. as Montesquieu visited the country estates of his fellow aristocrats, he gained backers who voted to make him a member of the Royal Society Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, PC, KG 1694 – 1773 a British statesman and man of letters

- 85. V.5 - Travels in England, 1729-1731 a. Montesquieu was the house guest of this famous luminary of the English Enlightenment. They had met in the Netherlands where Lord Chesterfield had been the British ambassador b. as Montesquieu visited the country estates of his fellow aristocrats, he gained backers who made him a member of the Royal Society c. 1726-28-Voltaire had been charged by the noble Rohan family in a lettre de cachet. He asked to have his imprisonment in the François-Marie Arouet Bastille commuted to exile in England. Thus 1694 – 1778 began his attempts to reform the French known by his nom de plume judicial system. His experience of England, Voltaire albeit from a less exalted station, also convinced him that France had a great deal to learn from their ancient foe

- 86. V.6- Considerations on the Greatness and Decline of Rome, 1734 Montesquieu returned to France in 1731, full of ideas and projects for future books. In 1734 he published his Considerations on the Greatness and Decline of Rome. Roman history was a convenient starting point for his favorite theories, soon to be developed more fully. Speaking of the capacity of a state to correct its own mistakes and abuses, Montesquieu mentions Rome, Carthage, Athens, and the Italian city-republics; lamenting their shortcomings in self-analysis and self-correction, he says: “ The government of England is wiser, because there is a body [Parliament] which examines it continuously and continuously examines itself; its errors never last long, and are often useful because of the spirit of attention they give to the people. In a word, a free government, that is, one that is always agitated, cannot be maintained if it is not capable of correction through its own laws.” Ebenstein, p. 416

- 87. In both Persian Letters and Considerations…, Montesquieu was able to evade the pervasive government censorship of his time. Voltaire and many other of the philosophes would be jailed for their publications. But Montesquieu took swipes at the oppressive régime of French absolutism in “coded” ways which his audience understood but which could be denied if challenged by the censors. The “Persians” often lamented the absolutism of Persia. The criticism of the Roman emperors was easily seen as an indictment of similar French royal abuses. jbp

- 88. De l’esprit des lois 1748

- 89. De l’esprit des lois A first edition offered recently 1748 at $11,000

- 90. MONTESQUIEU De l’esprit des lois, 1748 Thomas Nugent, trans., 1752. Cincinnati: Robert. Clarke & Co., 1873. BOOK I OF LAWS IN GENERAL CHAP. II - Of the Laws of Nature Antecedent to the [man-made] laws are those of nature, so called, because they derive their force entirely from our frame and existence. In order to have a perfect knowledge of these laws, we must consider man before the establishment of society: the laws received in such a state would be those of nature. ….Such a man would feel nothing in himself at first but impotency and weakness; his fears and apprehensions would be excessive; as appears from instances 9were there any necessity of proving it) of savages found in forests, trembling at the motion of a leaf, and flying at every shadow. In this state every man, instead of being sensible of his equality, would fancy himself inferior. There would therefore be no danger of their attacking one another; peace would be the first law of nature. (cont.)

- 91. In this state every man, instead of being sensible of his equality, would fancy himself inferior. There would therefore be no danger of their attacking one another; peace would be the first law of nature. (cont.) The natural impulse or desire which Hobbes attributes to mankind of subduing one another, is far from being well-founded. The idea of empire and dominion is so complex, and depends on so many other notions, that it could never be the first which occurred to human understanding. Hobbes inquires, “For what reason men go armed, and have locks and keys to fasten their doors, if they be not naturally in a state of war?” But is it not obvious, that he attributes to mankind before the establishment of society, what can happen but in consequence of this establishment, which furnishes them with motives for hostile attacks and self defense. Next to a sense of his weakness man would soon find that of his wants. Hence another law of nature would prompt him to seek for nourishment. Fear, I have observed, would induce men to shun one another; but the marks of this fear being reciprocal, would soon engage them to associate. Besides, this association would quickly follow from the very pleasure one animal feels at the approach of another of the same species Again, the attraction arising from the difference of sexes would enhance this pleasure; and the natural inclination they have for each other, would form a third law. ….and a fourth law of nature results from the desire of living in society.

- 92. VI. De l’esprit des lois, 1748 1.monarchy, republic, and despotism 2. separation of powers 3. role of the aristocracy 4. geopolitics and social sciences

- 94. Montesquieu’s is similar, yet simpler: despotism republic

- 95. What happened to government by the few? Montesquieu sees the aristocracy, his own class, as having a significant part to play in both the “good” kinds of governments: monarchy and republics. This role will be described below.

- 96. VI. 1. monarchy, republic, and despotism BOOK II OF LAWS IN DIRECTLY DERIVED FROM THE NATURE OF GOVERNMENT CHAP. I - Of the Nature of the three different Governments THERE are three species of government: republican, monarchial, and despotic. In order to discover their nature, it is sufficient to recollect the common notion, which supposes three definitions, or rather three facts: that a republican government is that in which the body, or only a part of the people, is possessed of the supreme power: monarchy, that in which a single person governs by fixed and established laws: a despotic government, that in which a single person directs every thing by his own will and caprice. This is what I call the nature of each government; we must now enquire into those laws which directly conform to this nature, and consequently are the fundamental institutions.

- 97. VI. 1. monarchy, republic, and despotism (cont.) CHAP. II - Of the Republican Government, and the Laws relative to Democracy When the body of the people is possessed of the supreme power, this is called democracy. When the supreme power is lodged in the hands of a part of the people, it is then an aristocracy. In a democracy the people are in some respects the sovereign, in others the subject. There can be no exercise of sovereignty but by their suffrages, which are their own will; now the sovereign’s will is the sovereign himself…. The people, in whom the supreme power resides, ought to have the management of every thing within their reach: what exceeds their abilities, must be conducted by their ministers…. The people are extremely well qualified for choosing those whom they are to entrust with part of their authority….But are they capable of conducting an intricate affair, of seizing and improving the opportunity and critical moment of action? No; this surpasses their abilities.

- 98. VI. 1. monarchy, republic, and despotism (cont.) BOOK III OF THE PRINCIPLES OF THE THREE KINDS OF GOVERNMENT CHAP. I - Difference between the Nature and Principle of Government. After having examined the laws relative to the nature of each government, we must investigate those which relate to its principle. There is this difference between the nature and principle of government: that the former is that by which it is constituted, the latter that by which it is made to act. One is its particular structure, the other the human passions which set it in motion. Now, laws ought to be no less relative to the principle than to the nature of each government. We must, therefore, inquire into the principle, which shall be the subject of this third book.

- 99. VI. 1. monarchy, republic, and despotism (cont.) CHAP. II -Of the Principle of different Governments. I have already observed, that it is the nature of a republican government, that either the collective body of the people, or particular families, should be possessed of the supreme power; of a monarchy, that the prince…of a despotic government….This enables me to discover their three principles; which are naturally derived from thence. I shall begin with republican government; and in particular with that of democracy. CHAP. III -Of the Principle of Democracy. There is no great share of probity necessary to support a monarchial or despotic government. The force of laws in one, and the prince’s arm in the other, are sufficient to direct and maintain the whole. But in a popular state, one spring more is necessary, namely virtue….

- 100. VI. 1. monarchy, republic, and despotism (cont.) CHAP. IX -Of the Principle of despotic Government. As virtue is necessary in a republic, and in a monarchy honour, so fear is necessary in a despotic government: with regard to virtue, there is no occasion for it, and honour would be extremely dangerous. Here the immense power of the prince is devolved entirely upon those whom he is pleased to entrust with the administration. Persons capable of setting a value upon themselves, would likely create disturbances. Fear must therefore depress their spirits, and extinguish the least sense of ambition. A moderate government may, whenever it pleases, and without the least danger, relax its springs. It supports itself by the laws, and by its own internal strength. But when a despotic prince ceases one single moment to lift up his arm...all is over: for, as fear, the spring of this government, no longer subsists, the people are left without a protector.

- 101. VI. 2. separation of powers BOOK XI OF LAWS WHICH ESTABLISH POLITICAL LIBERTY, WITH REGARD TO THE CONSTITUTION CHAP. III - In what Liberty consists It is true, that in democracies the people seem to act as they please; but political liberty does not consist in an unlimited freedom. In governments, that is, in societies directed by laws, liberty can consist only in the power of doing what we ought to will, and in not being constrained to do what we ought not to will. We must have continually present to our minds the difference between independence and liberty. Liberty is the right od doing whatever the laws permit; and if a citizen could do what they forbid, he would no longer possess liberty, because all his fellow-citizens would have the same power. CHAP. IV - The same Subject continued Democratic and aristocratic states are not in their own nature free. Political liberty is to be found only in moderate governments; and even in these, it is not always found. It is there only when there is no abuse of power; but constant experience shews us...(cont).

- 102. VI. 2. separation of powers (cont.) CHAP. IV - The same Subject continued Democratic and aristocratic states are not in their own nature free. Political liberty is to be found only in moderate governments; and even in these, it is not always found. It is there only when there is no abuse of power; but constant experience shews us...(cont.) that every man invested in power is apt to abuse it, and to carry his authority as far as it will go. Is it not strange, though true, to say, that virtue itself has need of limits? To prevent this abuse, it is necessary from the very nature of things, power should be a check to power. A government may be so constituted, as no man shall be compelled to do things to which the law does not oblige him,nor forced to abstain from things which the law permits. CHAP. V - Of the End or View of Different Governments Though all governments have the same general end, which is that of preservation, yet each has another particular object. Increase of dominion was the object of Rome; war, that of Sparta; religion, that of the Jewish laws; commerce, that of Marseilles; public tranquility, that of the laws of China; navigation, that of the laws of Rhodes; natural liberty, that of the policy of the Savages; in general, the pleasures of the prince, that of despotic states; that of monarchies, the prince’s and the kingdom’s glory…. (cont.)

- 103. VI. 2. separation of powers (cont.) CHAP. V - Of the End or View of Different Governments (cont.) despotic states; that of monarchies, the prince’s and the kingdom’s glory…. (cont.) One nation there is also in the world [Britain-jbp], that has for the direct end of its constitution, political liberty. We shall presently examine the principles on which this liberty is founded; if they are sound, liberty will appear in its highest perfection. To discover political liberty in a constitution, no great labour is requisite. If we are capable of seeing it where it exists, it is soon found, and we need not go far in search of it. CHAP. VI - Of the Constitution of England In every government there are three sorts of power: the legislative; the executive, in respect to things dependent on the law of nations [foreign policy-jbp]; and the executive, in regard to matters that depend on civil law. By virtue of the first, the prince or magistrate enacts temporary or perpetual laws….By the second, he makes peace or war….By the third, he punishes criminals, or determines the disputes that arise between individuals. The latter we shall call the judiciary power, and the other simply the executive power of the state….

- 104. VI. 2. separation of powers (cont.) CHAP. VI - Of the Constitution of England (cont.) When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; because apprehensions may arise, lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws, to execute them in a tyrannical manner. Again, there is no liberty if the judiciary power be not separated from the legislative and executive. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control; for the judge would then be legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with violence and oppression. There would be an end of every thing, were the same man, or the same body, whether of the nobles or of the people, to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, that of executing the public resolutions, and of trying the causes of individuals….

- 105. VI. 3. role of the aristocracy was that of the “makeweight.”

- 106. If the people became too powerful... ARISTOCRACY KING PEOPLE they would ally with the king to bring “balance”

- 107. If the people became too powerful... KING & ARISTOCRACY PEOPLE they would ally with the king to bring “balance”

- 108. If the king became too powerful... PEOPLE & ARISTOCRACY KING they would ally with the people to bring “balance”

- 109. VI. 3. role of the aristocracy (cont.) CHAP. VI - Of the Constitution of England (cont.) ...there are always persons distinguished by their birth, riches, or honours: but were they to be confounded with the common people, and to have only the weight of a single vote like the rest, the common liberty would be their slavery, and they would have no interest in supporting it, as most of the popular resolutions would be against them. The share they have, therefore, in the legislature ought to be proportioned to their other advantages in the state; which only happens when they form a body [House of Lords-jbp] that has a right to check the licentiousness of the people, as the people have a right to oppose any encroachment of theirs The legislative power is therefore to the body of the nobles, and to that which represents the people [House of Commons-jbp], each having their assemblies and deliberations apart, each their separate views and interests.

- 110. VI. 3. role of the aristocracy (cont.) Because Montesquieu was living in a censorious monarchy, he didn’t make the second case (the aristocracy siding with the people) explicit. But people in those days were used to “reading between the lines.” And so, the second case was there for all to see it. jbp

- 111. VI. 4. geopolitics and social sciences BOOK XIV OF LAWS AS RELATIVE TO THE NATURE OF THE CLIMATE CHAP. I - General Idea. If it be true that the temper of the mind, and the passions of the heart are extremely different in different climates, the laws ought to be relative both to the variety of those passions, and to the variety of those tempers. CHAP. II - Of the Difference of Men in different Climates A cold air constringes the extremities of the external fibers of the body; this increases their elasticity, and favours the return of the blood from the extreme parts of the heart. It contracts those very fibers; consequently it increases also their force. On the contrary a warm air relaxes and lengthens the extremes of the fibers; of course it diminishes their force and elasticity. (cont.)

- 112. VI. 4. geopolitics and social sciences CHAP. II - Of the Difference of Men in different Climates (cont.) the contrary a warm air relaxes and lengthens the extremes of the fibers; of course it diminishes their force and elasticity. (cont.) People are therefore more vigorous in cold climates. Here the action of the heart and the reaction of the extremities of the fibers are better performed, the temperature of the humours is greater, the blood moves freer towards the heart, and reciprocally the heart has more power. This superiority of strength must produce various effects; for instance, a greater boldness, that is, more courage; a greater sense of superiority, that is, less desire of revenge; a greater opinion of security, that is, more frankness, less suspicion, policy, and cunning. In short, this must be productive of very different tempers. Put a man into a close warm place, and for the reasons given, he will feel a great faintness. If under this circumstance you propose a bold enterprise to him, I believe you will find him very little disposed towards it; his present weakness will throw him into a despondency; he will be afraid of every thing, being in a state of total incapacity. (cont.)

- 113. VI. 4. geopolitics and social sciences CHAP. II - Of the Difference of Men in different Climates (cont.) despondency; he will be afraid of every thing, being in a state of total incapacity. (cont.) The inhabitants of warm countries are, like old men, timorous; the people in cold countries are, like young men, brave. If we reflect on the late wars, which are more recent in our memory, and in which we can better distinguish some particular effects that escape us at a greater distance of time; we shall find that the northern people transplanted into southern regions, did not perform such exploits as their countrymen, who, fighting in their own climate, possessed their full vigour and courage…. In cold countries, they have very little sensibility for pleasure; in temperate countries they have more; in warm countries, their sensibility is exquisite. As climates are distinguished by degrees of latitude, we might distinguish them also in some measure, by those of sensibility. I have been at the opera in England and in Italy, where I have seen the same pieces and the same performers; and yet the same music produces such different effects on the two nations: one is so cold and phlegmatic, and the other so lively and enraptured, that it seems almost inconceivable.

- 114. Criticism

- 115. “...The peculiar mixture of history and reason, of awareness of the past and concern for the future, of objective observation and desire for reform, has made Montesquieu one of the most influential political writers of the modern age, constantly reinterpreted, constantly rediscovered.” Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, p. 419

- 116. Nevertheless, he was limited by the reliability of his sources. Like many of his Enlightenment contemporaries, Montesquieu regarded information about the Indians of the Americas as evidence about man “in the state of nature.” The problem was that the observations were often based on hearsay and were prejudiced by the European colonials who often had little sympathy for their indignant and dangerous “neighbors.” Take this absurd anecdote: BOOK V, CHAP. XIII - An Idea of despotic Power When the savages of Louisiana are desirous of fruit, they cut the tree to the root, and gather the fruit. This is an emblem of despotic power. jbp

- 117. “...The Spirit of the Laws is surely the foundation work of modern political sociology.” …[the ideas] migrated across the Atlantic to the colleges of America, where Scots moral philosophers were much in demand, among them the Reverend John Witherspoon, the president of the College of New Jersey [today, Princeton University-jbp] and the teacher of James Madison.” Alan Ryan, On Politics, p. 518

- 118. “In the final analysis it is not easy to classify Montesquieu’s political philosophy. In his explicit beliefs there is a curious mixture of hatred of clericalism and despotism, profound concern for individual liberty, and a strong sense of aristocratic privilege, property, and class. Similarly, the implicit hypotheses of his political theory are complex: his faith in reason, humanity, and progress mark him out as a typical representative of the Age of Enlightenment. At the same time, Montesquieu was institution- minded to the point of venerating the past, and he therefore became suspect with many of the philosophes.” Ebenstein, Great Political Thinkers, p. 419

- 119. Rousseau, a near-contemporary French-speaking Genevan, like Montesquieu, was drawn northward to Paris, the “city of lights,” the center of 18th century enlightenment. But his social origins and his sense of the need for a radical break with the past marked him as profoundly different from the baron de la Brede et de Montesquieu. But that’s another story... jbp