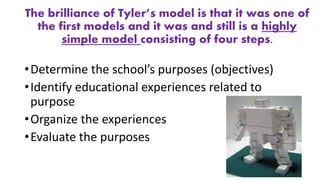

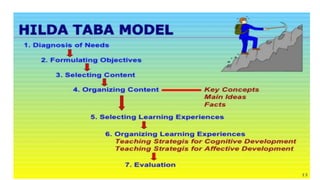

The document discusses various models of curriculum development, including Fullan's partnership model, Schwab's inquiry-based model, Tyler's objectives-focused model, Taba's order-based model, and Wheeler's cyclical model. It then describes a Jewish day school's use of a partnership model for its curriculum project, where each school appointed a coordinator to oversee development based on the school's mission and input from teachers. The project consultants provided training and feedback to help the coordinators and teacher teams develop the curriculum according to Tyler's 4-stage model.

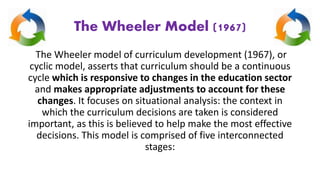

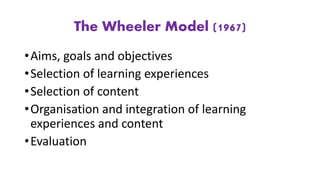

![The Wheeler Model (1967)

Once the cycle has been followed once, it begins again at step one and

continues onward to continuously improve the curriculum in the face

of any changes that may have been imposed or come about naturally. It

is different from other models in that ‘selection of learning

experiences’ comes before ‘selection of content’: it specifically gears

the content in the curriculum to learners, where most models follow

the opposite structure. Wheeler viewed evaluation as particularly

important, stating that ‘[e]valuation enables us to compare the actual

outcomes with the expected outcomes […] [without it] it is impossible

to know whether objectives have been realized, and if they have, to

what extent’ (Wheeler, 1976, cited in Carl, 2009).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jed426session2currdevelopmentprioritiesandchallenges-210906130349/85/JED-426-Session-2-Curriculum-Development-Priorities-and-Challenges-15-320.jpg)