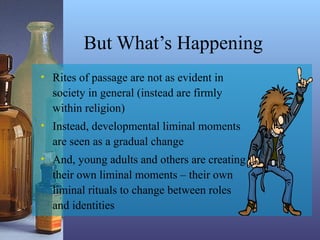

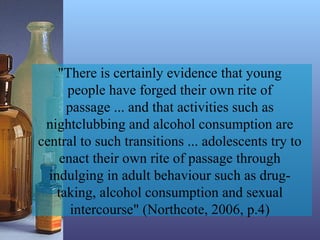

Binge drinking has become a rite of passage for teenagers in New Zealand according to an Alcohol Advisory Council speaker. Research shows that 785,000 adults regularly binge drink, and teenagers see adults tolerating and sometimes celebrating such behavior. Binge drinking has become normal and seen as a rite of passage that starts with parents buying alcohol for teenagers.