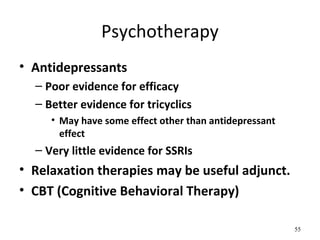

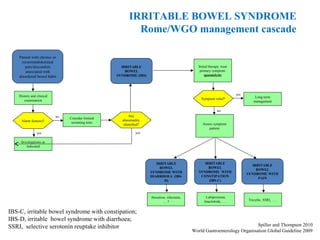

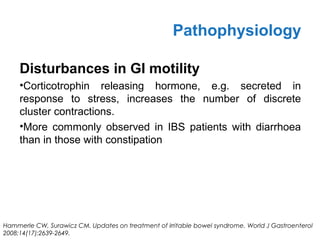

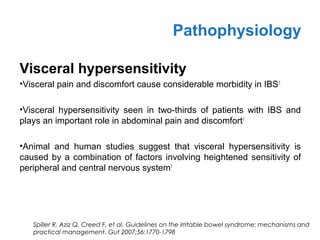

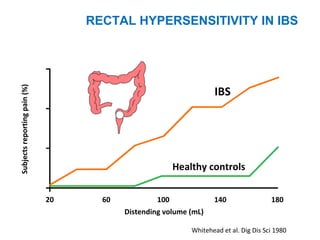

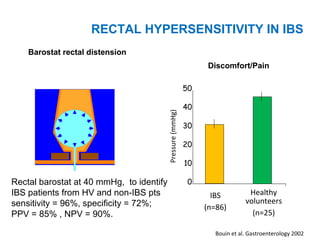

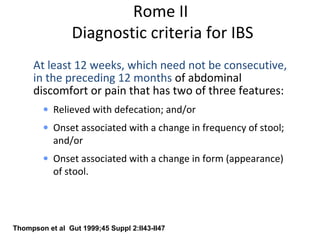

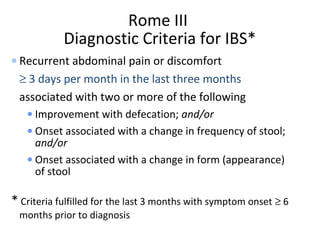

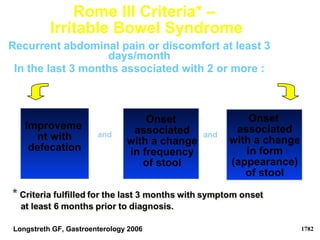

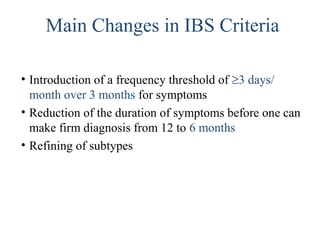

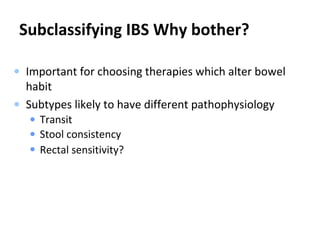

The document provides an overview of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), highlighting its definition, etiology, clinical features, and diagnostic criteria. It discusses the multifactorial nature of IBS, emphasizing the role of psychosocial factors, disturbances in gastrointestinal motility, and visceral hypersensitivity in its pathophysiology. The document also outlines treatment approaches based on symptom subtypes and the importance of patient education and reassurance.

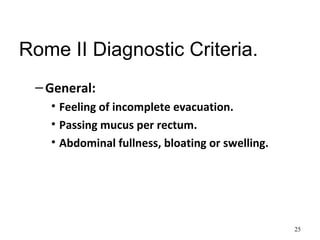

![Rome II Diagnostic Criteria.

• Supportive symptoms.

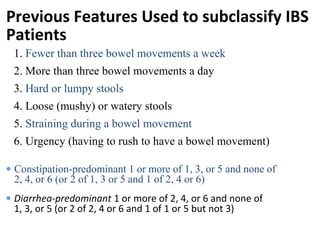

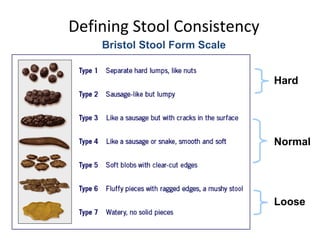

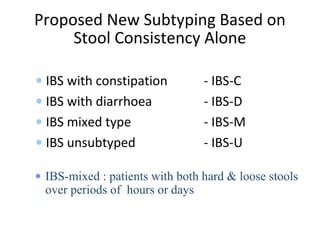

– Constipation predominant: one or more of:

• Bowel movement less than 3 times a week.

• Hard or lumpy stools.

• Straining during a bowel movement.

– Diarrhoea predominant: one or more of:

• More than 3 bowel movements per day.

• Loose [mushy] or watery stools.

• Urgency.

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/irritablebowelsyndromemzaffarabad-160327113206/85/Irritable-bowel-syndrome-24-320.jpg)

![Associated Symptoms

• In people with IBS in hospital OPD.

– 25% have depression.

– 25% have anxiety.

• Patients with IBS symptoms who do not

consult doctors [population surveys] have

identical psychological health to general

population.

• In one study 70% of women IBS sufferers

have dyspareunia.

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/irritablebowelsyndromemzaffarabad-160327113206/85/Irritable-bowel-syndrome-45-320.jpg)