This research paper examines pragmatic competence among highly proficient Japanese speakers of English, particularly in the context of invitations, to explore the impacts of pragmatic transfer from their first language. It aims to analyze characteristics of their invitations compared to native speakers and assess sociopragmatic and pragmalinguistic errors. The study further investigates the implications for English as a Second Language (ESL) education and the nuances of performing speech acts within different cultural contexts.

![27

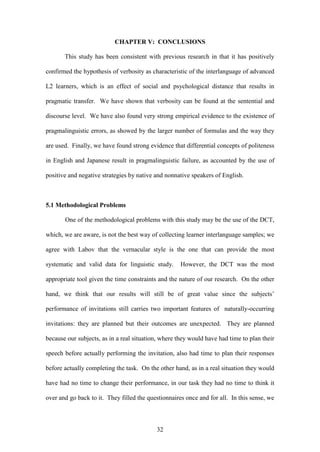

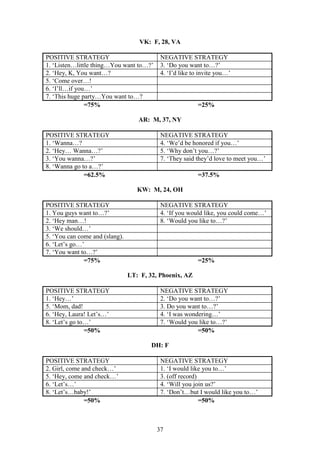

As can be seen, NS tended to use positive politeness in their invitations. The

categories found included showing interest and noticing (greetings and similar

expressions: ‘hi’, ‘hey’), use of ‘in-group’ language (mention of first name, ‘man’,

‘guys’, ‘let’s…’, ‘we…’[inclusive], ‘yo’, ‘baby’, ‘ma’, and slang), and showing and

seeking agreement (‘what do you say we…?’, ‘wanna?’ you want to…?’). They used it

up to 61.25%, counting only their occurrence in each item in the DCT as one. On the

other hand, they only used negative strategies 38.75%, especially in items 4 (inviting

one’s boss or professor, they used it 100% of the times) and 7 (inviting one’s friend to

meet one’s parents), which required this kind of strategy, being consistent with Brown

and Levinson’s model. Seven people used positive strategies 62.5% and more, 2 people

used positive and negative strategies in the same proportion (50%), and only one person

used more negative strategies (62.5%) than positive strategies (37.5%). When looking

his the data, we found out that this person happens to be married to a Japanese woman.

The specific formulas used and the percentages for each individual participant can be

seen in Tables 2a and 2b in Appendix 3.

The NNS, on the other hand, used positive strategies only 23.75%, and tended to

use negative strategies on 76.25% of the times. None of them used positive strategies

more than 37.5%, being very consistent in that respect. The percentages are shown

below in Figure 6b.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/invitations-prg-trnsfr-231016044211-1beb3cea/85/Invitations-Pragmatic-Transfer-27-320.jpg)