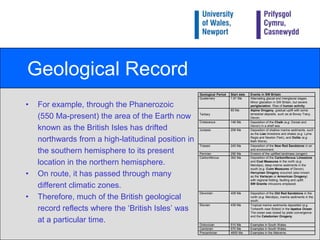

The document introduces approaches to reconstructing past environments from geological records, which provide evidence of environmental variation and change over time. Key points include:

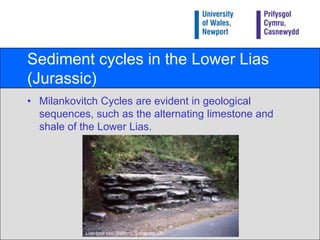

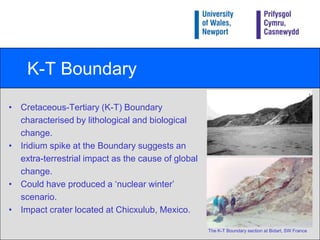

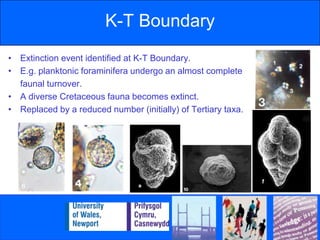

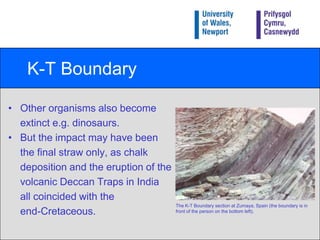

1) The geological record reveals periods of both local and global environmental change through features like sediment cycles and extinction events.

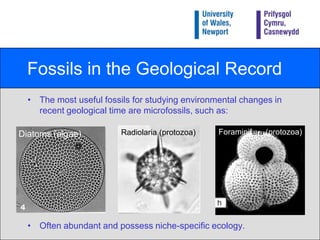

2) Fossils are very useful proxies for indicating environmental conditions, and microfossil analysis can provide information about factors like temperature and ocean chemistry.

3) Reconstructing past environments is challenging and uncertain, but tools like isotope analysis of microfossils have improved understanding of global environmental shifts.