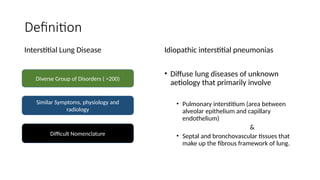

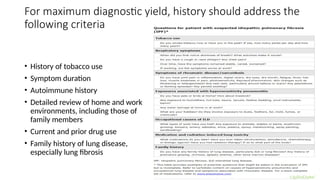

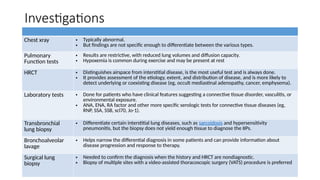

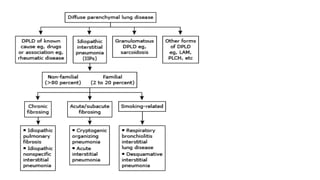

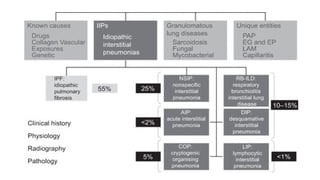

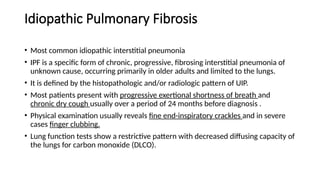

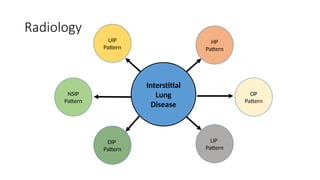

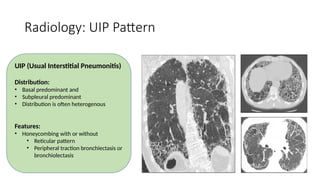

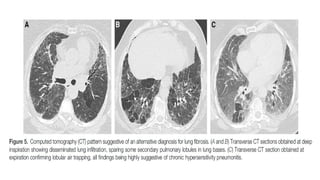

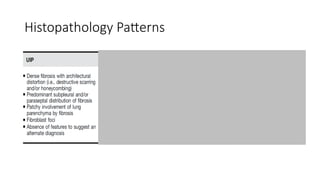

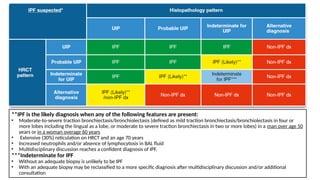

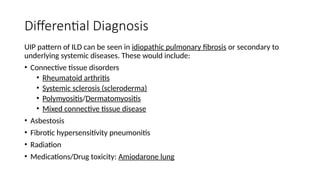

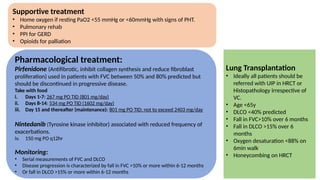

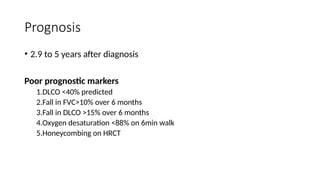

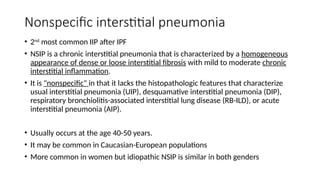

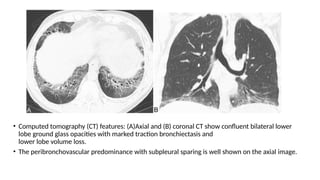

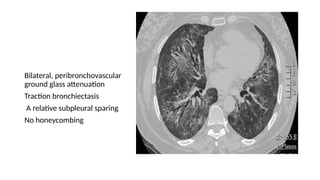

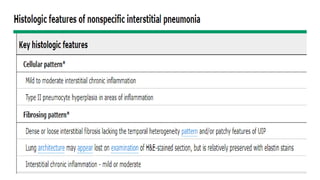

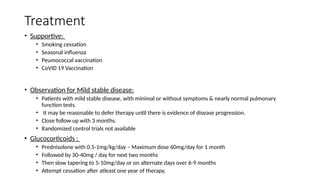

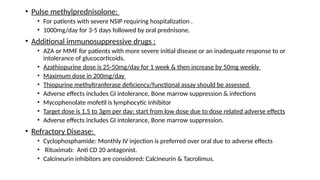

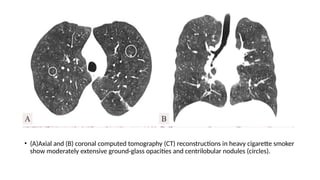

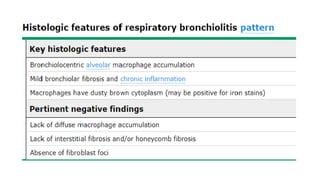

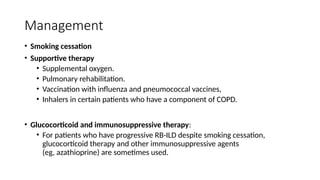

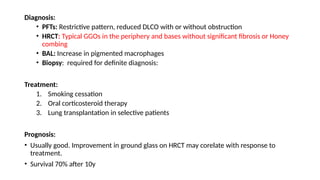

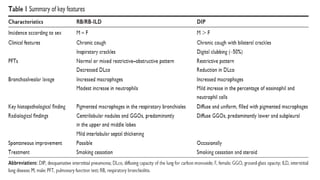

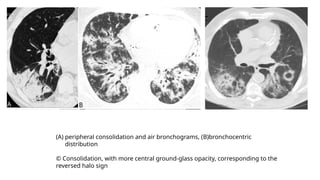

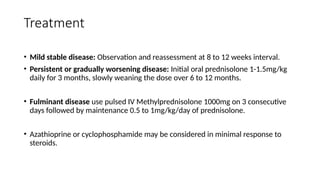

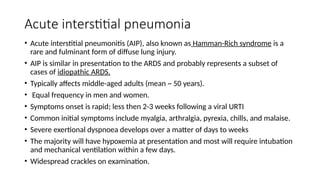

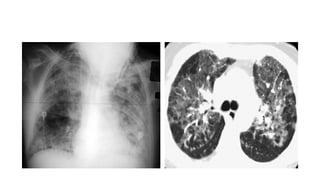

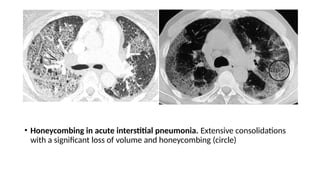

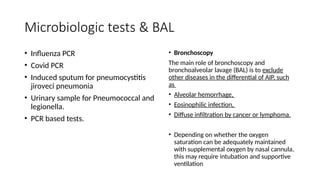

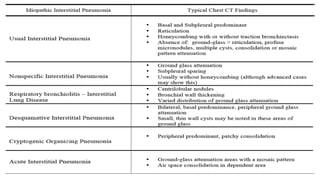

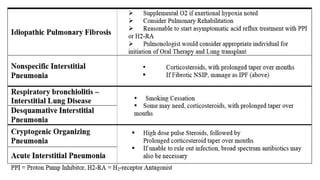

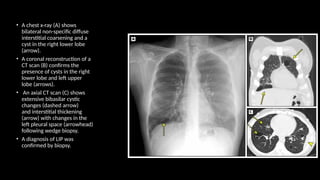

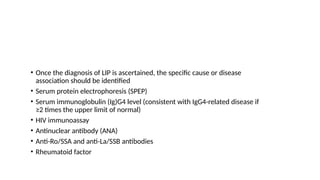

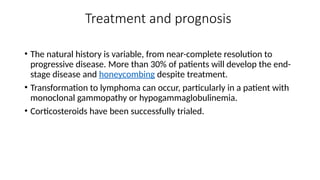

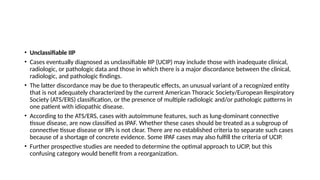

The document outlines idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) and specifically focuses on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) as a chronic, progressive lung disease of unknown cause, characterized by a restrictive pattern in pulmonary function tests and specific histopathological patterns on imaging. It discusses the diagnostic process, including the use of high-resolution CT scans and biopsies, and highlights the importance of considering a detailed patient history for accurate diagnosis. Treatment options include supportive care, pharmacological interventions with antifibrotic agents, and lung transplantation for advanced cases, with a prognosis generally more favorable for nonspecific interstitial pneumonia compared to IPF.