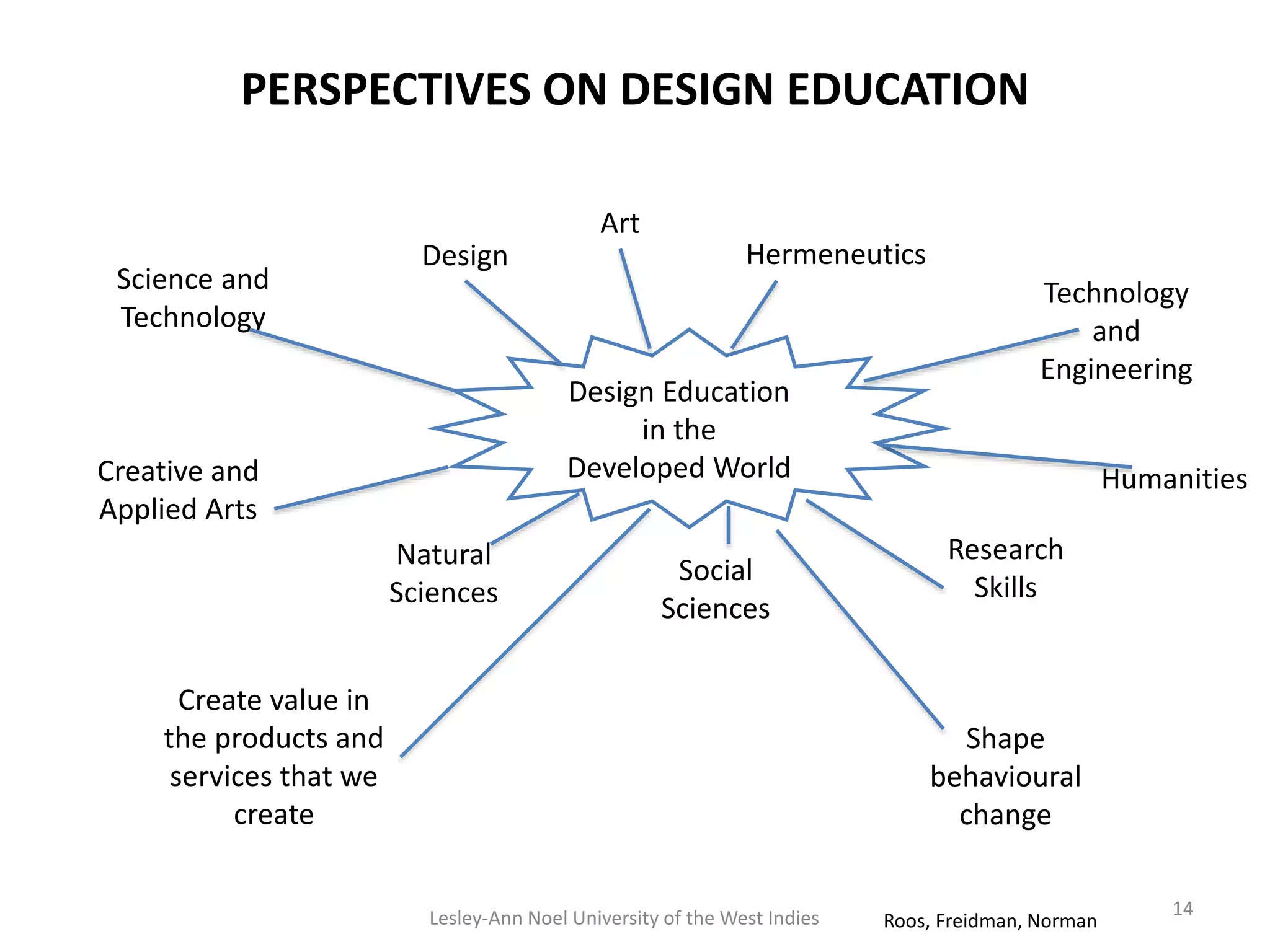

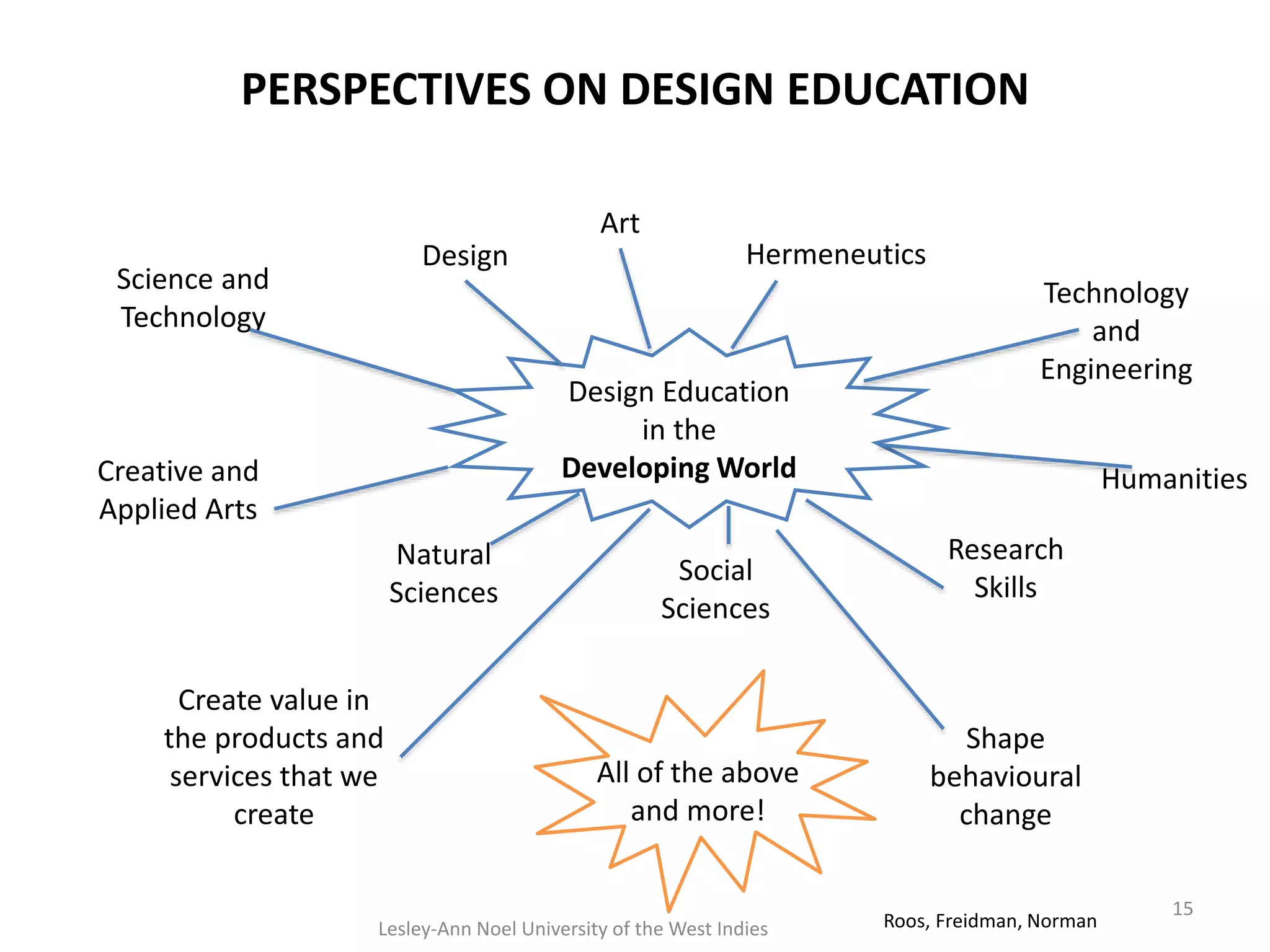

Design education can play an important role in developing economies by helping industries become more competitive and by solving social and environmental problems. Designers in developing countries need skills in areas like sustainability, culture, entrepreneurship, and advocacy to address challenges specific to those contexts. While the need for design may seem less obvious in vulnerable economies, designers there can help diversify industries, promote investment, and support countries' development agendas through locally-generated solutions.