National Qualifications X837/76/11 History provides marking instructions for the British, European and World History exam. It outlines general marking principles, including using positive marking and awarding the better mark if a candidate answers two parts instead of one. It also provides detailed marking instructions for different question types, such as essays. For essays, it identifies how many marks should be awarded for historical context, conclusions, use of knowledge, analysis and evaluation. The document aims to ensure marking is consistent across examiners by specifying how marks should be allocated for different elements of candidate responses.

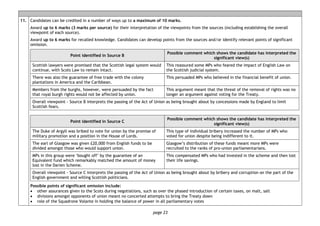

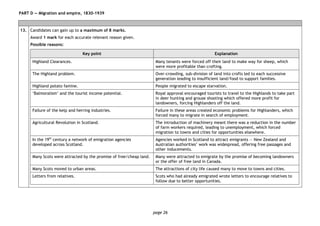

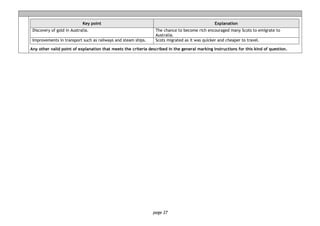

![page 94

Discontent among the peasantry:

• the massive economic growth had been paid for largely by grain exports, which often led to starvation in the countryside. Worsening

economic conditions had caused famines in 1897, 1898 and 1901

• the peasants had several grievances such as high redemption payments, high taxes, land hunger and poverty

• there was a wave of unrest in 1902 and 1903, which gradually increased by 1905.There were various protests such as timber cutting, seizure

of lords’ land — sometimes whole estates were seized and divided up, labour and rent strikes, as well as attacks on landlords’ grain stocks

• political opposition groups encouraged peasants to boycott paying taxes and redemption payments and refuse to be conscripted into the

army.

Political problems:

• although reluctant to rule when he came to the throne in 1894, Nicholas II was determined to maintain autocratic rule. He was, however,

remote from his people

• Nicholas was a family man, dominated by his wife and preoccupied with his son’s haemophilia. He appointed all his ministers and based his

decisions on the censored reports they sent to him

• the middle classes were aggrieved at having no participation in government, and angry at the incompetence of the government during the

war with Japan

• there was propaganda from middle-class groups. Zemstvas [local councils] called for change and the Radical Union of Unions was formed to

combine professional groups

• the gentry tried to convince the Tsar to make minor concessions

• national minorities harboured the desire for independence and began to assert themselves. Georgia, for example declared its independence.

Bloody Sunday:

• on 9/22 January 1905, Father Gapon, an Orthodox priest, attempted to lead a peaceful march of workers and their families to the Winter

Palace to deliver a petition asking the Tsar to improve the conditions of the workers. Marchers were fired on and killed by troops

• many people saw this as a brutal massacre by the Tsar and his troops. Bloody Sunday greatly damaged the traditional image of the Tsar as

the ‘Little Father’, the Guardian of the Russian people

• reaction to Bloody Sunday was strong. There was nationwide disorder; strikes in urban areas and terrorism against government officials and

landlords, much of which was organised by the Social Revolutionaries.

Any other relevant factors.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021hhistory-markinginstructions-230220153753-d5e302f3/85/Higher-History-exam-2021-marking-instructions-94-320.jpg)

![page 113

Military threat:

• Rearmament of Germany under the Nazis. Expansion of army and development of Luftwaffe all in contravention of the Treaty of Versailles

gave Hitler the means to threaten and act

• the extent to which it was the threat of military force which was used rather than military force itself — for example Czechoslovakia in 1938;

and the extent to which military force itself was effective and/or relied on an element of bluff — for example Rhineland

• German remilitarization of Rhineland — Hitler’s claimed provocation by the Franco-Soviet Mutual Assistance Treaty and moved troops into

the demilitarized Rhineland, which bordered France. His generals had warned Hitler that the army was not strong enough, but the Allies

were unprepared and failed to act, increasing Hitler’s confidence

• Czechoslovakia — Hitler turned his attention to Czechoslovakia in 1938. He claimed the German minority in Czechoslovakia was being

persecuted. Hitler threatened to take action to protect fellow Germans. German military maneuvers on the border by 750,000 German

troops were part of the pressure Hitler brought to bear on the Czechs. Germany was given the Sudetenland as a result of the Munich

agreement

• Unification of Italian colonies of Cyreniaca and Tripolitania into Italian North Africa in 1934.

Pacts and alliances:

• the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact between Nazi Germany and Poland signed on 26 January 1934 — normalised relations between Poland

and Germany, and promised peace for 10 years. Germany gained respectability and calmed international fears

• 18 June, 1935 Britain and Germany signed the Anglo-German Naval Agreement which allowed Germany parity in the air and to build up its

naval forces to a level that was 35% of Britain’s. Germany was also allowed to build submarines to a level equal of Britain’s. Britain did not

consult her allies before coming to this agreement

• Rome-Berlin axis — treaty of friendship signed between Italy and Germany on 25 October 1936

• Pact of Steel an agreement between Italy and Germany signed on 22 May 1939 for immediate aid and military support in the event of war

• Anti-Comintern Pact between Nazi Germany and Japan on 25 November 1936. The pact directed against the Communist International

(Comintern) but was specifically directed against the Soviet Union. In 1937 Italy joined the Pact

• Munich Agreement — negotiations led to Hitler gaining Sudetenland and weakening Czechoslovakia

• Nazi Soviet Non-Aggression Pact August 1939. Hitler and Stalin bought time for themselves. For Hitler it seemed war in Europe over Poland

unlikely. Poland was doomed. Britain had lost the possibility of alliance with Russia.

Role of Hitler and Mussolini:

• Hitler’s foreign policy had an ideological role as seen in Mein Kampf. The desire to avenge the Treaty of Versailles, ‘reunite’ Germanic

people and gain Lebensraum for a growing German population all motivated foreign policy in the 1930s

• Mussolini wanted to re-establish the greatness of the Roman Empire and saw military action as the sign of a great power. Also the desire that

the Mediterranean be ‘Our Sea’ [Mare Nostrum] helped dictate Italian actions over Corfu, Fiume and Libya.

Any other relevant factors.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021hhistory-markinginstructions-230220153753-d5e302f3/85/Higher-History-exam-2021-marking-instructions-113-320.jpg)

![page 118

52. Context

The Nazi occupation of the Sudetenland could be justified in the eyes of appeasers as Hitler was absorbing fellow Germans into Greater

Germany. However, subsequent actions by the Nazis could not be supported in this way and any illusion of justified grievances evaporated as

Hitler made demands on powers such as Poland, which eventually led to war.

Nazi-Soviet Pact:

• Pact — diplomatic, economic, military co-operation; division of Poland

• unexpected — Hitler and Stalin’s motives

• put an end to Anglo-French talks with Russia on guarantees to Poland

• Hitler was freed from the threat of Soviet intervention and war on two fronts

• Hitler’s belief that Britain and France would not go to war over Poland without Russian assistance

• Hitler now felt free to attack Poland

• given Hitler’s consistent, long-term foreign policy aims on the destruction of the Versailles settlement and lebensraum in the east, the Nazi-

Soviet Pact could be seen more as a factor influencing the timing of the outbreak of war rather than as one of its underlying causes

• Hitler’s long-term aims for destruction of the Soviet state and conquest of Russian resources — lebensraum

• Hitler’s need for new territory and resources to sustain Germany’s militarised economy

• Hitler’s belief that British and French were ‘worms’ who would not turn from previous policy of appeasement and avoidance of war at all

costs

• Hitler’s belief that the longer war was delayed the more the balance of military and economic advantage would shift against Germany.

Other factors:

Changing British attitudes towards appeasement:

• events in Bohemia and Moravia consolidated growing concerns in Britain

• Czechoslovakia did not concern most people until the middle of September 1938, when they began to object to a small democratic state

being bullied. However, most press and population went along with it, although level of popular opposition often underestimated

• German annexation of Memel [largely German population, but in Lithuania] further showed Hitler’s bad faith

• actions convinced British government of growing German threat in south-eastern Europe

• Guarantees to Poland and promised action in the event of threats to Polish independence

• Military Service Act (April 1939) called up all men 20―22 for military training.

Occupation of Bohemia and the collapse of Czechoslovakia:

• British and French realisation, after Hitler’s breaking of Munich Agreement and invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, that Hitler’s word

was worthless and that his aims went beyond the incorporation of ex-German territories and ethnic Germans within the Reich

• promises of support to Poland and Romania

• British public acceptance that all attempts to maintain peace had been exhausted

• Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain felt betrayed by the Nazi seizure of Czechoslovakia, realised his policy of appeasement towards Hitler

had failed, and began to take a much harder line against the Nazis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021hhistory-markinginstructions-230220153753-d5e302f3/85/Higher-History-exam-2021-marking-instructions-118-320.jpg)

![page 127

Role of Reagan:

• unlike many in the US administration Reagan actively sought to challenge Soviet weakness and strengthen the West in order to defeat

Communism. In 1983 he denounced the Soviet Union as an ‘Evil Empire’

• under Reagan the US began a massive military upgrade to improve their armed forces. This included developing intermediate nuclear

weapons such as the Pershing and Cruise missiles as well as the proposed Strategic Defence Initiative missile programme which challenged

the belief in MAD

• Reagan was very charming when he met Gorbachev and visited Soviet Union. He saw the opportunity for compromise in dealing with the new

Soviet leader and acted to push arms control as a result.

Any other relevant factors.

[END OF MARKING INSTRUCTIONS]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021hhistory-markinginstructions-230220153753-d5e302f3/85/Higher-History-exam-2021-marking-instructions-127-320.jpg)

![page 11

PART B — The age of the Reformation, 1542−1603

5. Candidates can gain up to a maximum of 8 marks.

Award 1 mark for each accurate relevant reason given.

Possible reasons:

Key point Explanation

Pluralism. Some churchmen held several church posts at the same

time taking the income from each and paying other, often

unqualified, men to do the jobs day-to-day.

This practise drew criticism from reformers who argued churchmen

were serving their own interests and not those of the people.

The wealth of the Catholic Church [as contrasted with the poverty of

most of the people]. The Catholic Church was even richer than the

monarchy.

Reformers argued that the Church spent too much time

accumulating wealth which was not then used to supply the needs

of the people through the provision of well-trained priests, well

maintained church buildings, education and help for the poor.

Indulgences drew particular criticism from reformers. This drew criticism from reformers because they argued that

indulgences exploited people and people’s credulity.

The lifestyles of many churchmen. By the 1540s many priests and

monks and bishops had relationships and often children.

Reformers argued that far too many churchmen were hypocritical

as they were meant to be celibate.

The failure of Catholic reform 1542―1560. Reforming councils were too little, too late and did nothing to stem

the flow of criticism.

The growth of printing. Printing presses produced Protestant literature in the form of

books, cheap pamphlets and Bibles in English.

The ‘Rough Wooing’ (1544―1547). English invasions led to the destruction of the infrastructure of the

Church.

The death of Cardinal Beaton. It removed from the Scottish scene the leading figure in the

Catholic Church and one who had opposed Protestantism and

internal reform.

The persecution and martyrdom of Protestants. The effect of this was to galvanise support for Protestants because

the martyrs were seen as heroic figures.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021hhistory-markinginstructions-230220153753-d5e302f3/85/Higher-History-exam-2021-marking-instructions-138-320.jpg)

![page 13

6. Candidates can gain marks in a number of ways up to a maximum of 8 marks.

Award a maximum of 4 marks for evaluative comments relating to author, type of source, purpose and timing.

Award a maximum of 2 marks for evaluative comments relating to the content of the source.

Award a maximum of 3 marks for evaluative comments relating to points of significant omission.

Examples of aspects of the source and possible comments:

Aspect of the source Possible comment

Author: issued in the name of Mary, Queen of Scots. Useful because since it is from the queen, it sets out what her

position as a Catholic monarch is going to be with regard to the

Reformation of 1560.

Type of source: Royal Proclamation. Useful because it is a declaration of what her policy is with regard

to the religion of the realm.

Purpose: to give reassurance that there will be no attempt to reverse

the Reformation Parliament of 1560.

Useful because it highlights the fact Mary’s religious policy was

unclear and confusing.

Timing: 25 August 1561. Useful because the proclamation was issued six days after her

return to Scotland indicating the pressure she was under from

Protestants to accept the Reformation.

Content Possible comment

Neither Lords nor anyone else, either privately or publicly, should, for

the moment, attempt to bring in any new or sudden changes to the

religious settlement [of 1560] publicly and universally standing at Her

Majesty’s arrival in Scotland.

Useful because it highlights Mary’s decision to accept the religious

settlement established by the 1560 parliament.

Her Majesty further wishes it to be known that anyone who seeks to

upset the existing religious settlement shall be viewed as a rebellious

subject and a troublemaker and shall be punished accordingly.

Useful because it highlights Mary’s attempts to discourage Catholics

from seeking to overturn the Protestant settlement arrived at in

1560.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021hhistory-markinginstructions-230220153753-d5e302f3/85/Higher-History-exam-2021-marking-instructions-140-320.jpg)

![page 35

PART E — The impact of the Great War, 1914−1928

17. Candidates can gain up to a maximum of 8 marks.

Award 1 mark for each accurate relevant reason given.

Possible reasons:

Key point Explanation

Scots’ volunteered in large numbers. Scots made a significant contribution to the numbers on the Western

Front.

Scots’ enthusiasm for joining saw the emergence of units based

around workplace/Scottish institutions.

This led to the formation of locally raised battalions, especially in

Glasgow and Edinburgh, serving together on the Western Front.

Scots were often used as ‘shock troops’ when assaulting German

trenches.

Scots soldiers were effective troops, building on the martial tradition

that they had built up over the previous century in expanding and

defending the British Empire.

35,000 Scots troops took part in the Battle of Loos in 1915. Scots role at the Battle of Loos in 1915 was significant in terms of

numbers.

Scots role at the Battle of Loos was important militarily. Scots were involved in successes, such as the 15th

[Scottish]

division’s involvement in the taking of Loos itself.

Scots won 5 Victoria Crosses during the battle with actions such as

that of Piper Daniel Laidlaw becoming legendary.

Scots were important in reinforcing the message of heroism and

determination of Scots troops.

One third of casualties at Loos were Scots. Scots suffered disproportionate casualties at Loos showing their

importance.

Fifty-one Scottish battalions took part at the Battle of the Somme in

1916.

Scots played in important part in the battle in terms of numbers.

Forty-four Scottish battalions took part in the battle on the first day

at the Battle of Arras in 1917.

Scots played an important role at Arras. If we include the seven

Canadian-Scottish units then it was the largest concentration of

Scottish soldiers ever to have fought together.

Scots born General Haig was Commander-in-Chief from late 1915. Haig ordered the Somme offensive but was criticised for the scale of

losses.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021hhistory-markinginstructions-230220153753-d5e302f3/85/Higher-History-exam-2021-marking-instructions-162-320.jpg)

![page 42

• Radicalism grew and is associated with Red Clydeside and the role of the Shop Stewards Movement, strikes during the war, and the

Independent Labour Party

• George Square riots in 1919 and perception of a Bolshevik threat led to government intervention

• success of Independent Labour in getting people elected, for example John Wheatley, who was prominent during the war campaigning

against conscription and rent increases, was elected on to Glasgow City Council then became a MP in the 1922 General Election. Others

elected included David Kirkwood and James Maxton

• role of the socialist John McLean during and after the war

• role of women politically due to events during the war and franchise reform: Mary Barbour, Agnes Dollan, etc

• formation of National Party of Scotland by John MacCormick and Roland Muirhead with support from intellectuals like Hugh MacDiarmid. It

had little electoral impact in this period.

Any other valid point of explanation that meets the criteria described in the general marking instructions for this kind of question.

[END OF MARKING INSTRUCTIONS]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2021hhistory-markinginstructions-230220153753-d5e302f3/85/Higher-History-exam-2021-marking-instructions-169-320.jpg)