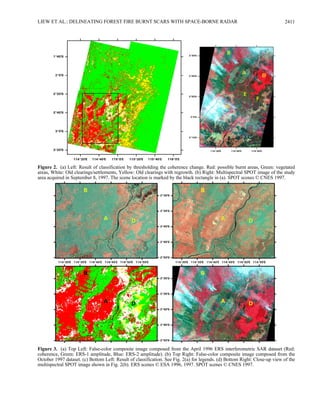

This document summarizes a study that used radar imagery from the European Remote Sensing satellites ERS-1 and ERS-2 to map burnt forest areas in South Kalimantan, Indonesia following extensive fires in 1997. The researchers analyzed coherence images from 1996 and 1997 to identify areas that showed increased coherence after the fires, indicating vegetation clearing. They identified 552,000 hectares of burnt scars out of the 3.6 million hectare study area. Comparison to a multispectral SPOT image from September 1997 validated the radar analysis in delineating burnt areas. The study demonstrated the capability of radar interferometry to map fire-affected areas through changes in vegetation, providing an alternative to optical imagery during times of smoke and

![GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 26, NO. 16, PAGES 2409-2412, AUGUST 15, 1999

Copyright 1999 by American Geophysical Union. Paper number 1999GL900189. 0094-8276/99/1999GL900189$05.00

Delineating Land/Forest Fire Burnt Scars with ERS

Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar

S. C. Liew, L. K. Kwoh, K. Padmanabhan, O. K. Lim and H. Lim

Centre for Remote Imaging, Sensing and Processing, National University of Singapore, Republic of Singapore

Abstract. Cloud-penetrating C-band synthetic aperture radar

imagery acquired during two ERS-1/2 tandem missions (April

1996 and October 1997) was used in mapping burnt areas in

South Kalimantan, Indonesia, during the 1997 Southeast Asia

forest fire episode. Vegetated areas were classified by their

low interferometric coherence in both the 1996 and 1997

imagery while the burnt areas were delineated by their

increased coherence in 1997. A total of 552 kha of land was

found to be burnt scars out of the 3.6 Mha area surveyed. The

results were validated using a multispectral SPOT image of

the area acquired in September 1997.

Introduction

In 1997, during the dry season from July to November,

fires raged out of control in the tropical forest of Sumatra and

Kalimantan, Indonesia. In addition to transboundary pollution

in the form of smoke haze, the effects of forest fires on the

environment include the loss of biodiversity, loss of forests as

carbon sinks and emission of greenhouse gases with potential

contribution to global warming [Levine, 1991, 1996; Zepp,

1994].

In order to assess the impacts of the fires to the

environment, it is important to acquire information such as the

location of fires, spatial extent of burnt areas, types of land

cover on fire and geographical distribution of fires. Satellite

remote sensing is able to provide some of the essential

information [Malingreau, 1990]. Remote sensing studies of

fires are usually carried out using optical/Infrared sensors

[Kaufman et al., 1990] such as the NOAA-AVHRR

[Robinson, 1991; Matson, 1987], LANDSAT-TM [Pereira

and Setzer, 1993] and SPOT-HRV [Liew et al., 1998]. The

AVHRR sensors on board the NOAA Polar Orbiting Satellites

are able to detect the presence of fire hot spots using channel

3 (3.8 µm) and provide images showing the spatial

distribution and temporal evolution of fire hot spots

[Robinson, 1991; Matson, 1987]. The channels 1 and 2 of the

same sensors also provide information about the aerosols

characteristics and distribution of the smoke haze [Ferrare et

al., 1990]. However, due to the coarse resolution (1.1 km) of

the AVHRR sensors, the exact locations of fires and the types

of land cover on fire cannot be determined. Measurement

from hot spot images generally overestimates the area burnt

but underestimates the total fire count [Malingreau, 1990;

Kaufman et al., 1990]. Burnt areas can be mapped with high-

resolution optical sensors such as the LANDSAT-TM (30 m)

and SPOT-HRV (20 m), using the spectral characteristics of

the fire scars. Individual smoke plumes can be observed in the

images and hence the precise locations of the active fire areas

can be determined using the high-resolution images. The

types of land cover on fire can also be determined from the

spectral and contextual features of the fire areas. One major

limitation of optical/infrared remote sensing imagery lies in

the inability of optical/infrared radiation in penetrating clouds

and thick haze.

In this paper, we report on the use of the cloud-penetrating

C-band SAR on-board the ERS-1 and ERS-2 satellites in

mapping burnt areas during the 1997 Southeast Asia forest

fire episode. SAR backscatter intensity and interferometric

coherence have been used in forest mapping and monitoring

[LeToan et al., 1996; Wegmuller and Werner, 1995; Stussi et

al., 1997]. In particular, tropical forests are known to have a

constant backscattering coefficient (σo

) between -7 and -6 dB

in C-band. The interferometric coherence of the vegetated

area is typically low compared with the clearcuts or sparsely

vegetated area. If multitemporal SAR data of an area of

interest are acquired, clearings of forests/vegetation can be

detected by an observed change in σo

and/or an increase in

coherence of the area. Unlike optical/infrared sensors, SAR is

unable to detect hot spots or smoke plumes directly associated

with fires. It is thus not able to tell whether the clearings are

due to fires or other means. However, if fires have been

known to occur in an area of interest, the extent of fire

affected areas can be mapped using SAR backscattered

intensity and interferometric coherence signatures.

Methods

The location map of the study area covering four ERS

frames is shown in Fig. 1 and the dataset used in the study is

shown in Table 1. The study area is located in South

Kalimantan, near the town of Banjarmasin. This area is

known to be severely affected by fires from observations

using NOAA-AVHRR and SPOT imagery. The ERS data

were acquired during two tandem missions in April 1996 and

October 1997 and processed to the level of Single-Look

Complex (SLC). Altogether 8 pairs of tandem-SLC data were

used. Each pair of the SLC images were first co-registered

and the coherence (γ1,2) and intensity (I1, I2) images were

generated by,

γ1 2

1 2

1 1 2 2

, =

∗

∗ ∗

s s

s s s s

(1)

I s s kk k k= =

∗

( , )1 2 (2)

where s1, s2 are the complex pixel values of the two

coregistered SLC images and the brackets denote statistical](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ec767e19-b2b6-49c8-a250-99097330dd60-160208140021/75/GRL99-1-2048.jpg)