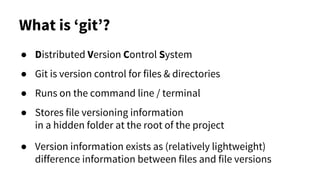

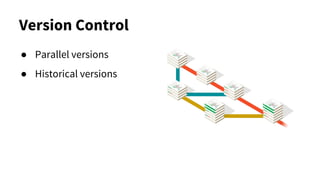

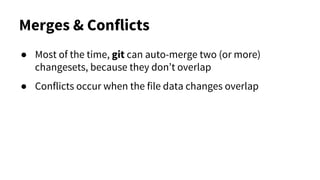

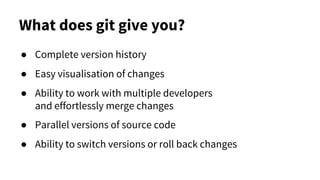

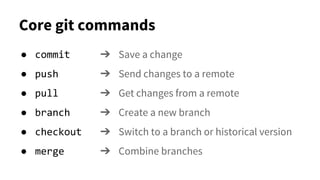

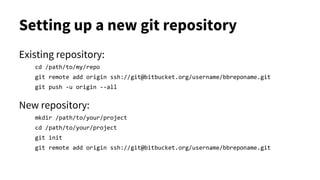

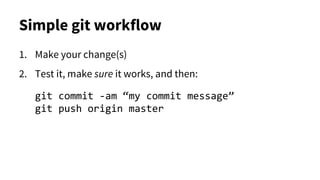

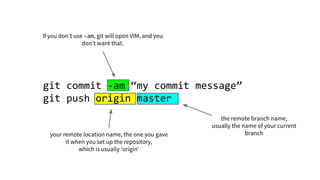

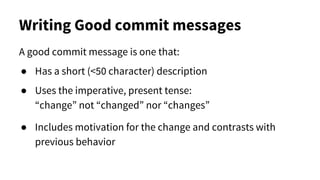

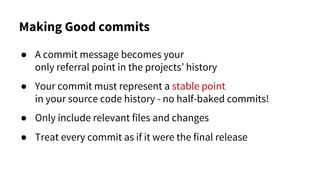

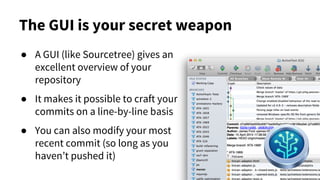

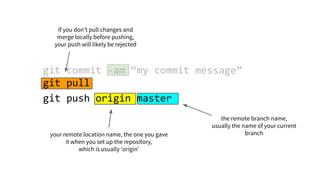

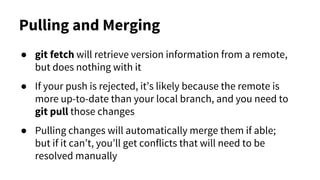

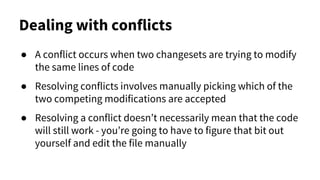

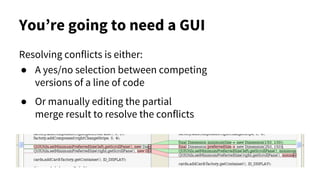

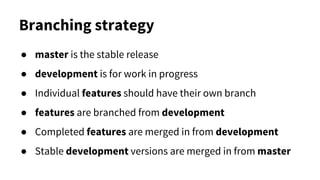

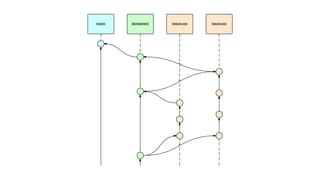

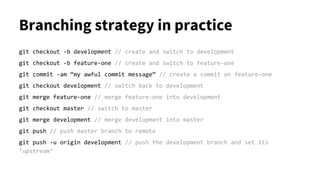

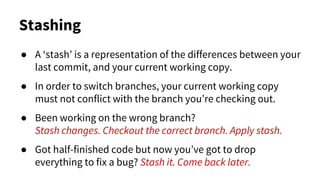

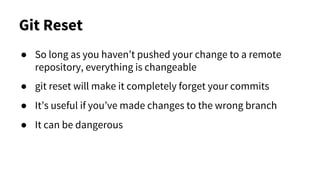

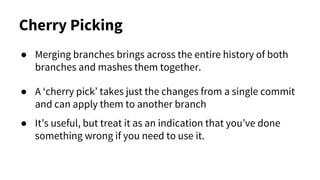

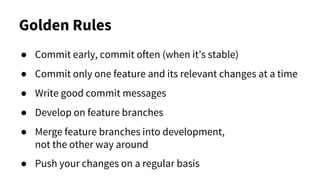

The document provides a comprehensive overview of Git, a distributed version control system used for managing files and directories. It covers core concepts such as version control, branching strategies, essential commands, conflict resolution, and best practices for committing changes and writing commit messages. Additionally, it discusses tools like GUI applications and advanced Git features, emphasizing the importance of effective collaboration among developers.