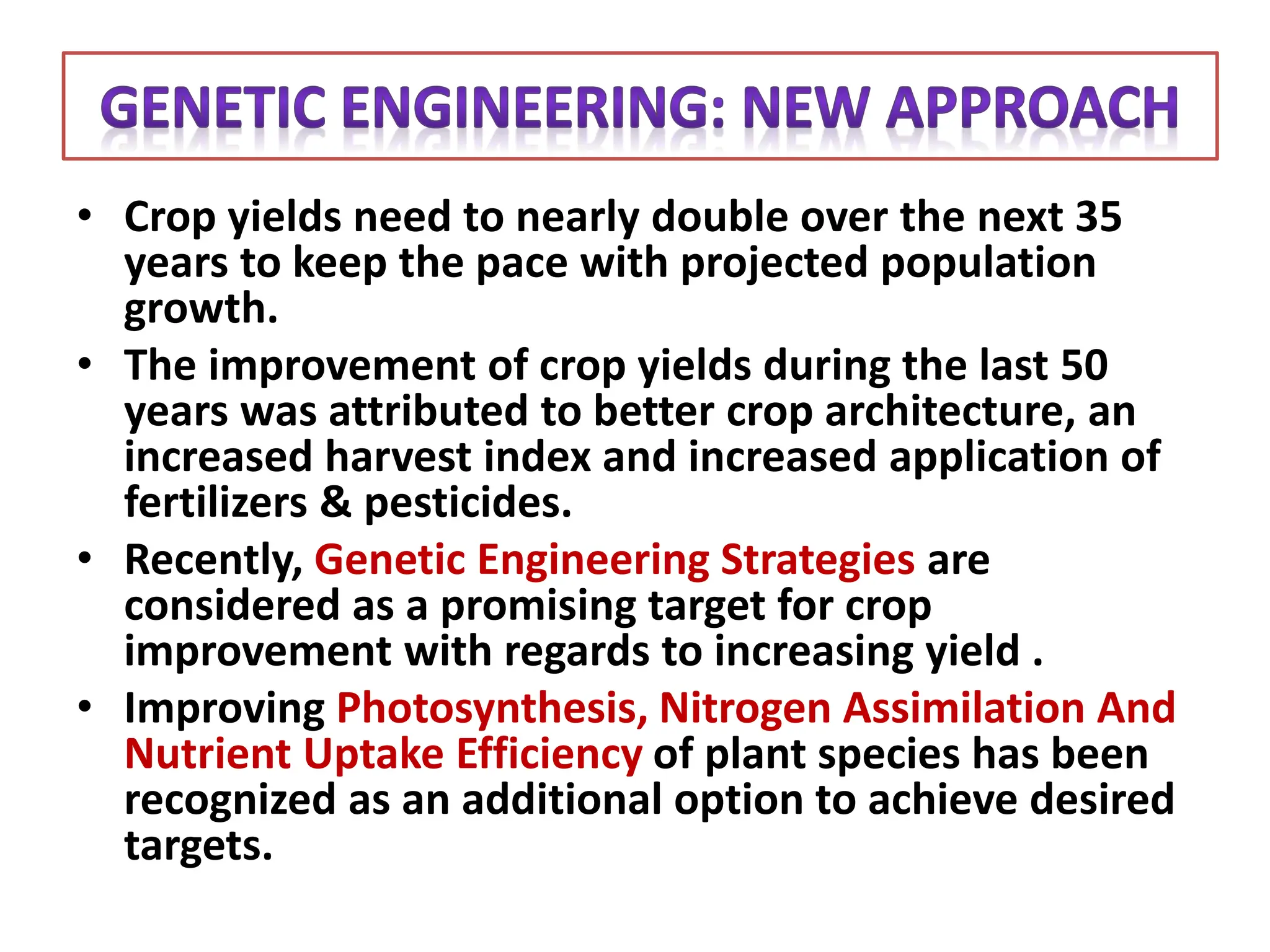

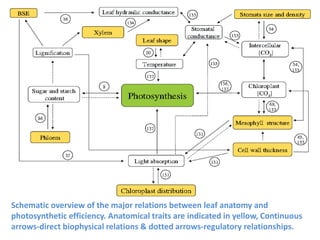

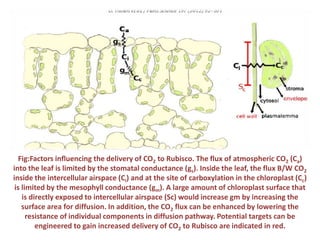

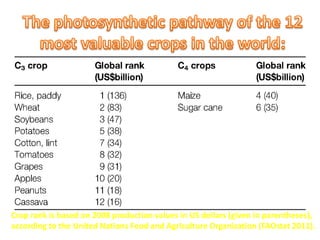

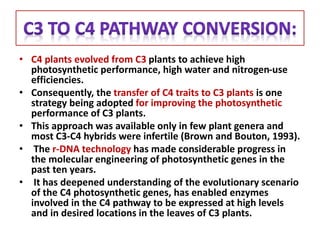

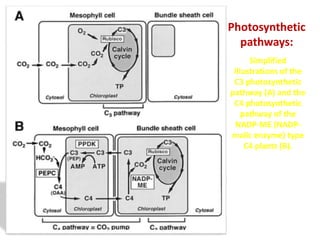

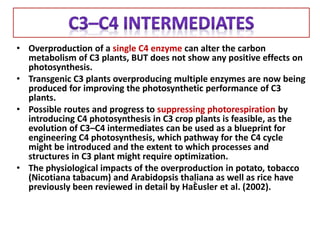

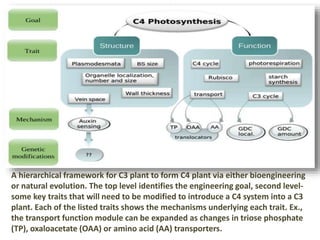

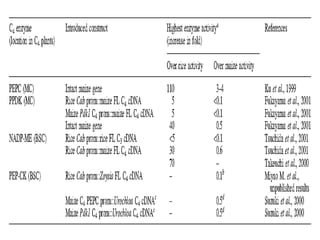

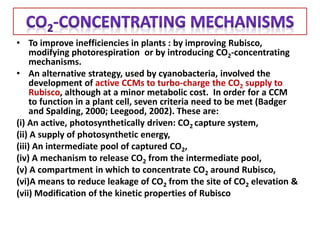

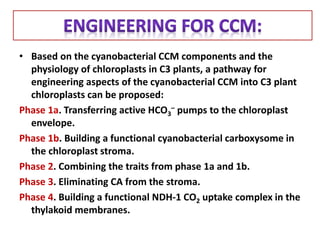

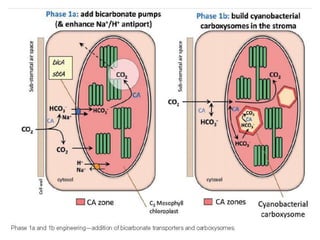

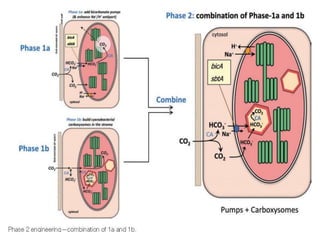

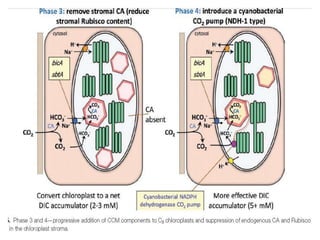

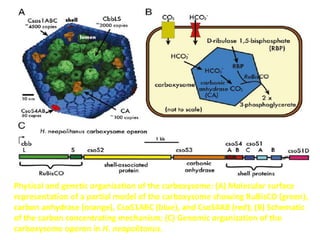

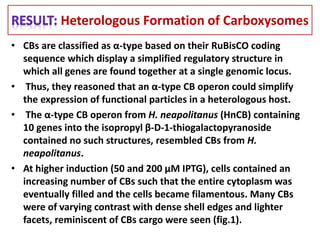

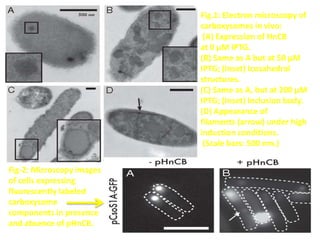

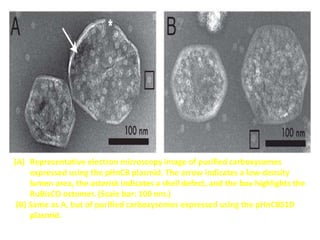

To meet projected population growth, crop yields must nearly double in the next 35 years, and strategies such as genetic engineering and improvements in photosynthesis and nutrient uptake efficiency are being pursued. Engineering traits from C4 plants into C3 plants represents a key strategy to enhance photosynthetic performance. Advances in molecular biology have facilitated the production and study of carboxysomes, which are crucial for carbon fixation and could serve as a model for developing synthetic organelles in plants.