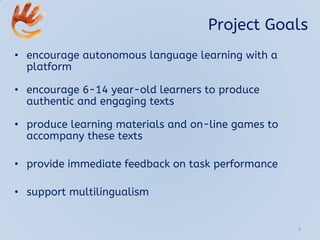

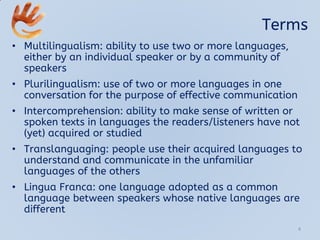

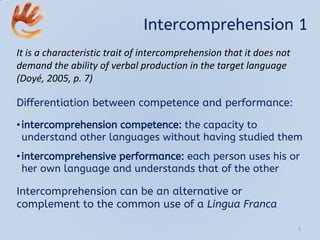

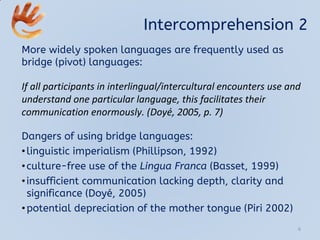

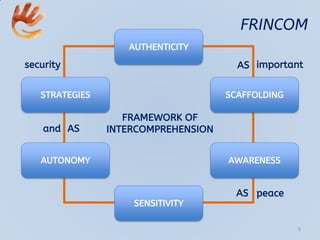

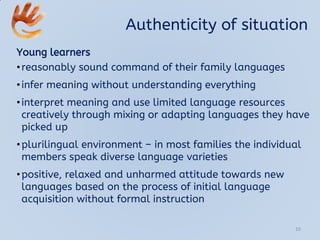

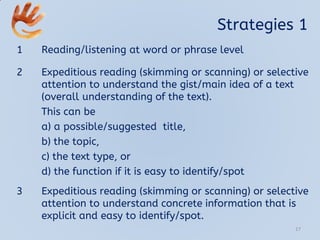

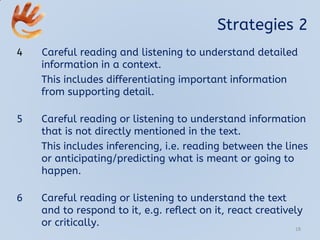

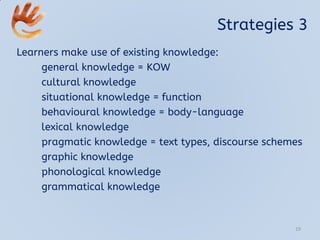

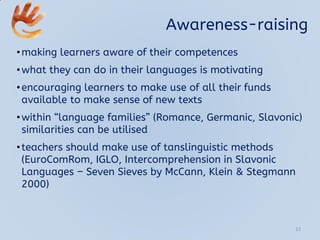

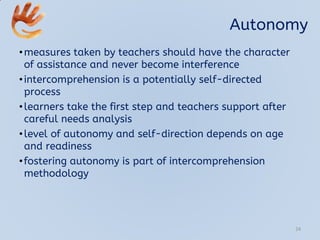

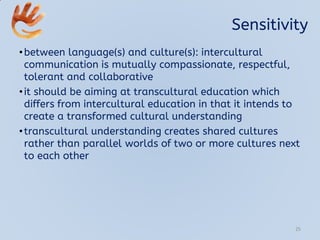

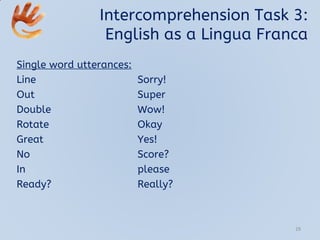

This document outlines a framework for promoting language acquisition among children in multilingual contexts, emphasizing intercomprehension, plurilingualism, and translanguaging as key concepts. It details project goals focused on fostering authentic language learning experiences, supporting autonomous learning, and providing strategies for effective communication across languages. The document also discusses the importance of authenticity in tasks and environments to enhance language understanding among learners.