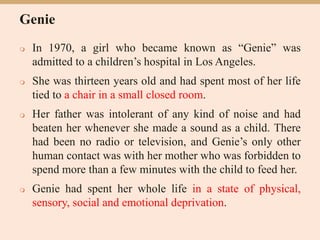

Children acquire language with remarkable ease and success despite the complexity of language and their limited cognitive abilities. This is known as the "logical problem" of language learning. There are several reasons why innate linguistic knowledge must underlie acquisition: 1) Children's knowledge exceeds the input they receive. 2) Linguistic constraints and principles cannot be learned through general intelligence. 3) Universal developmental patterns cannot be explained by language-specific input alone. The logical problem suggests language acquisition relies on innate, language-specific mechanisms.

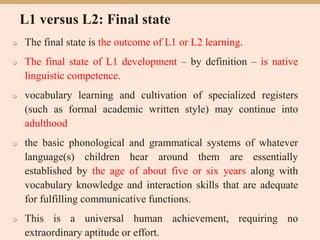

![Stages of L1 acquisition

Pre-language stage

The earliest use of speech-like sounds has been described as

cooing.

During the first few months of life, the child gradually

becomes capable of producing sequences of vowel-like sounds,

particularly high vowels similar to [i] and [u].

By four months of age, the developing ability to bring the

back of the tongue into regular contact with the back of the

palate allows the infant to create sounds similar to the velar

consonants [k] and [ɡ], hence the common description as

“cooing” or “gooing” for this type of production.

纯啼哭声、咕咕声、咿咿呀呀、笑(招手)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week3-4foundationsofsecondlanguageacquisition-230411160107-ac808385/85/Foundations-of-Second-Language-Acquisition-pptx-25-320.jpg)

![Stages of L1 acquisition

The one-word stage

Between twelve and eighteen months, children begin to

produce a variety of recognizable single-unit utterances.

“milk,” “cookie,” “cat,” “cup” and “spoon”

Other forms such as [ʌsæ] may occur in circumstances that

suggest the child is producing a version of What’s that

饿、抱、不舒服

We sometimes use the term holophrastic (meaning a single

form functioning as a phrase or sentence) to describe an

utterance that could be analyzed as a word, a phrase, or a

sentence.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week3-4foundationsofsecondlanguageacquisition-230411160107-ac808385/85/Foundations-of-Second-Language-Acquisition-pptx-26-320.jpg)