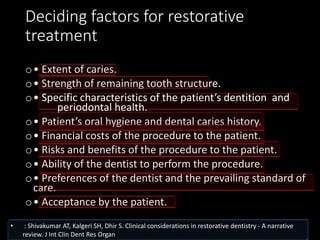

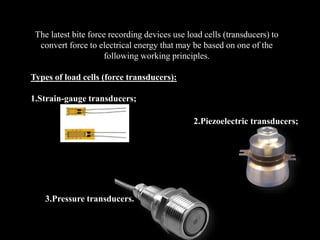

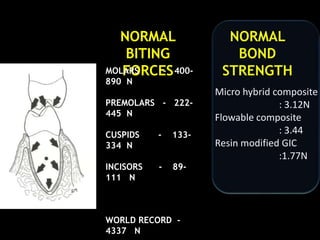

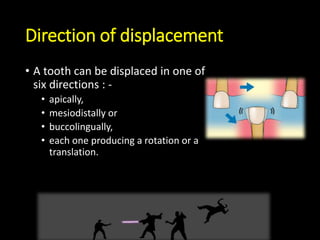

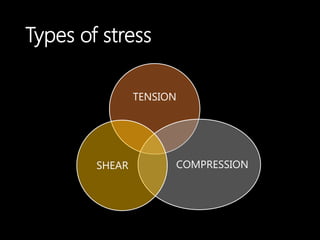

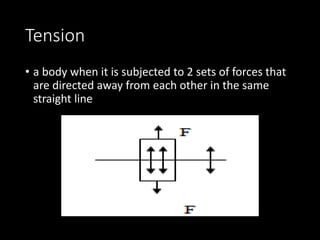

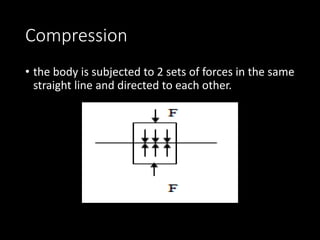

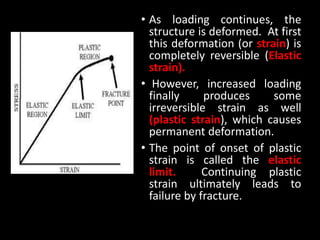

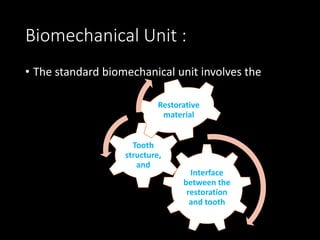

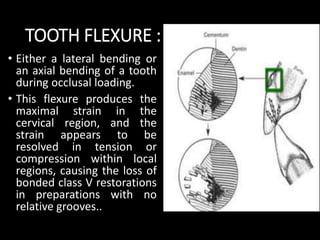

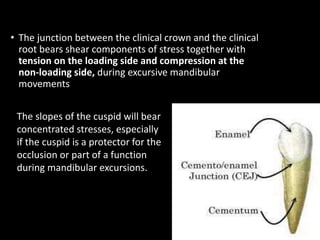

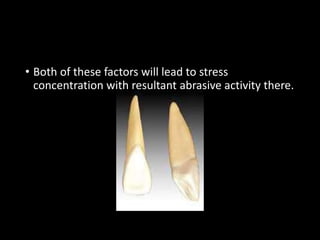

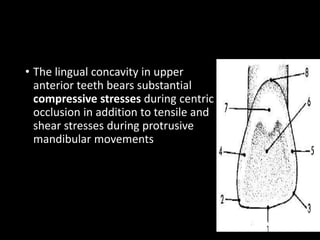

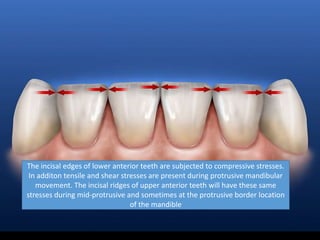

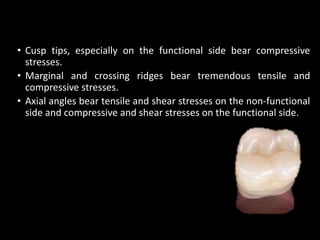

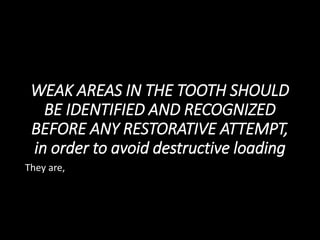

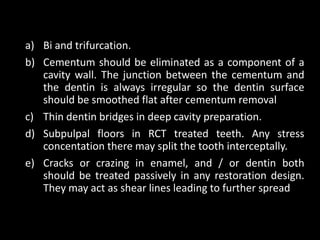

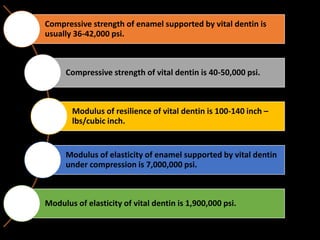

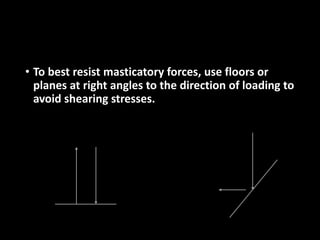

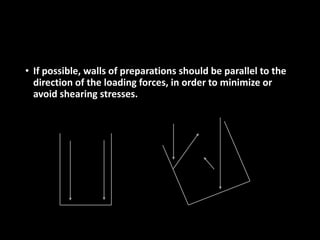

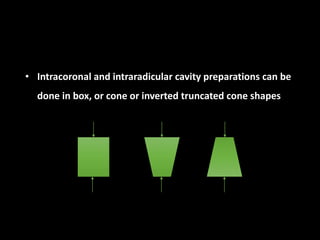

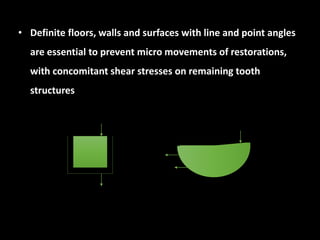

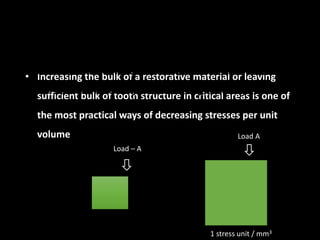

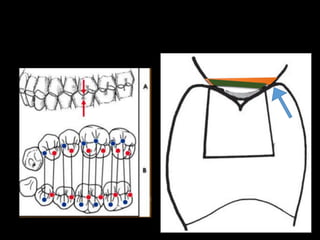

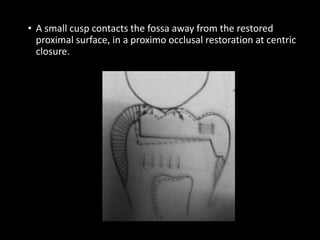

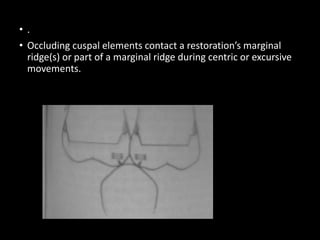

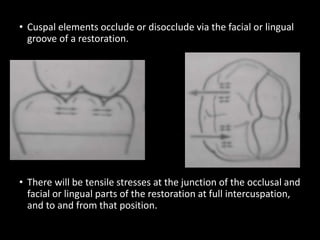

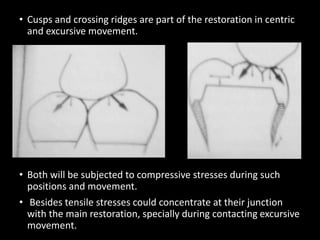

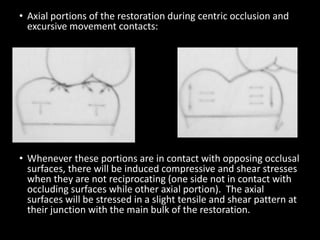

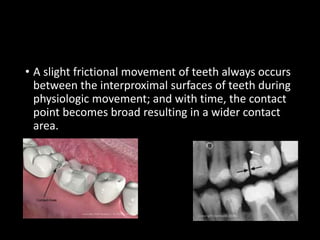

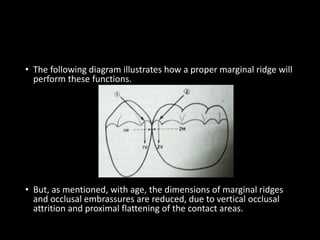

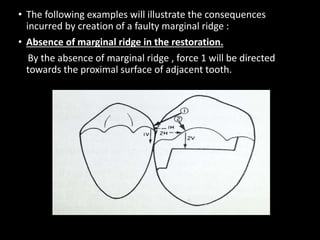

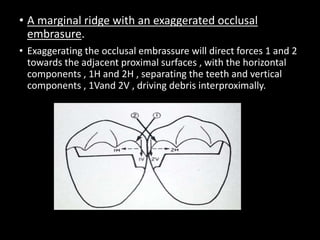

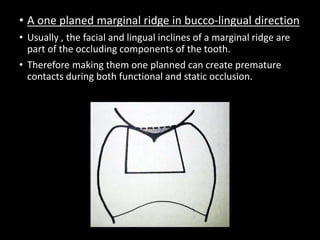

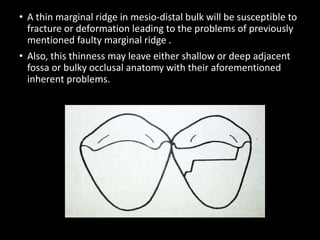

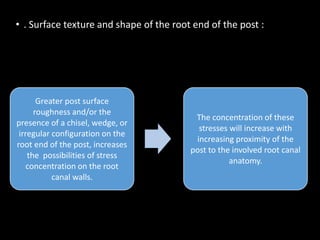

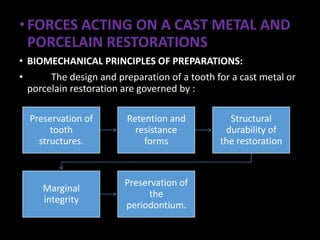

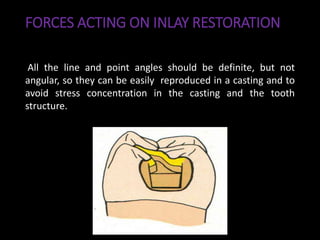

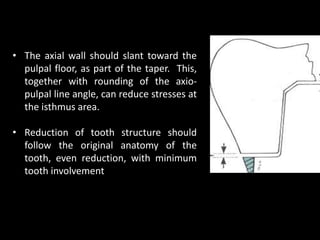

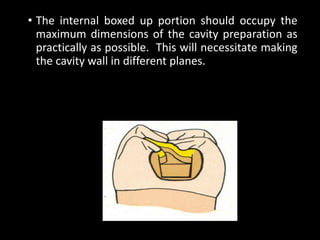

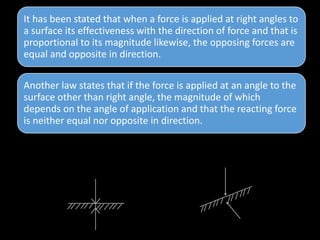

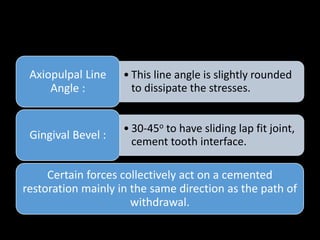

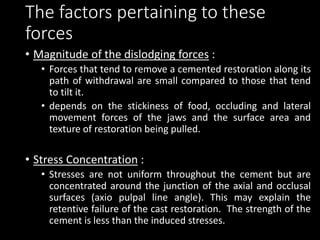

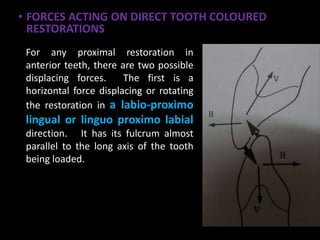

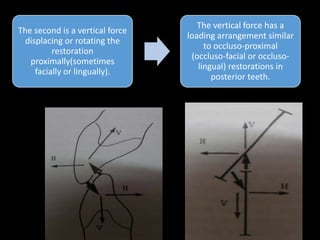

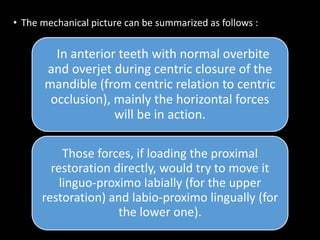

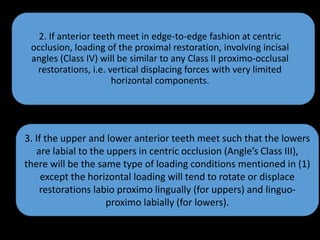

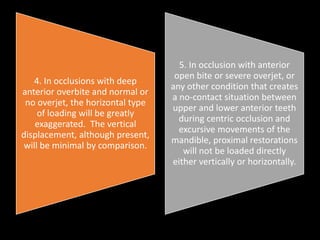

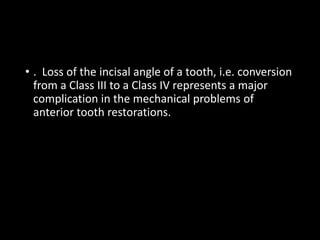

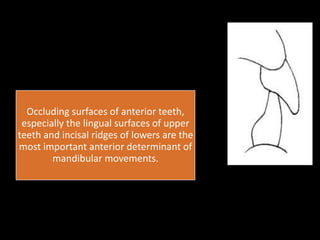

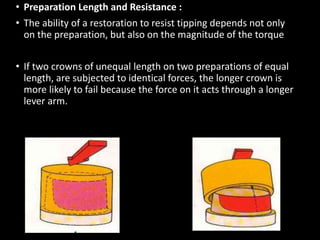

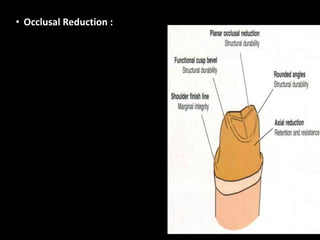

This document discusses various biomechanical considerations that are important for restorative dentistry. It covers topics like the forces acting on teeth, stress patterns on different types of teeth, weak areas of teeth, and mechanical properties of dental materials. It emphasizes the importance of understanding stress transfer and how restorations can impact this. It also addresses obtaining resistance form for tooth structures and occlusal considerations when restoring teeth. The overall goal is to design restorations that can withstand biting forces and minimize stress on remaining tooth structures.