This document discusses biomechanics and mechanics of tooth movement in orthodontics. It covers:

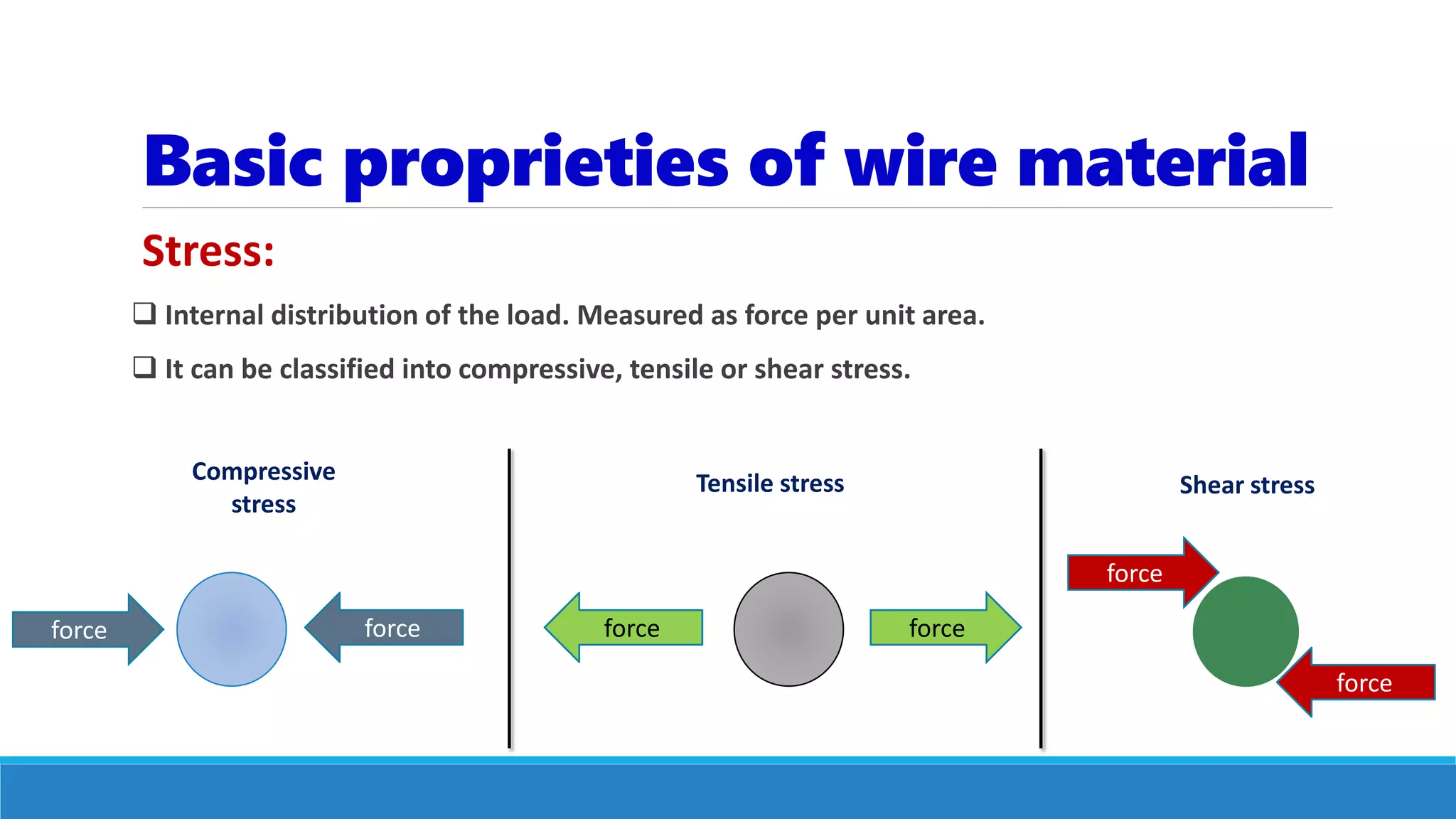

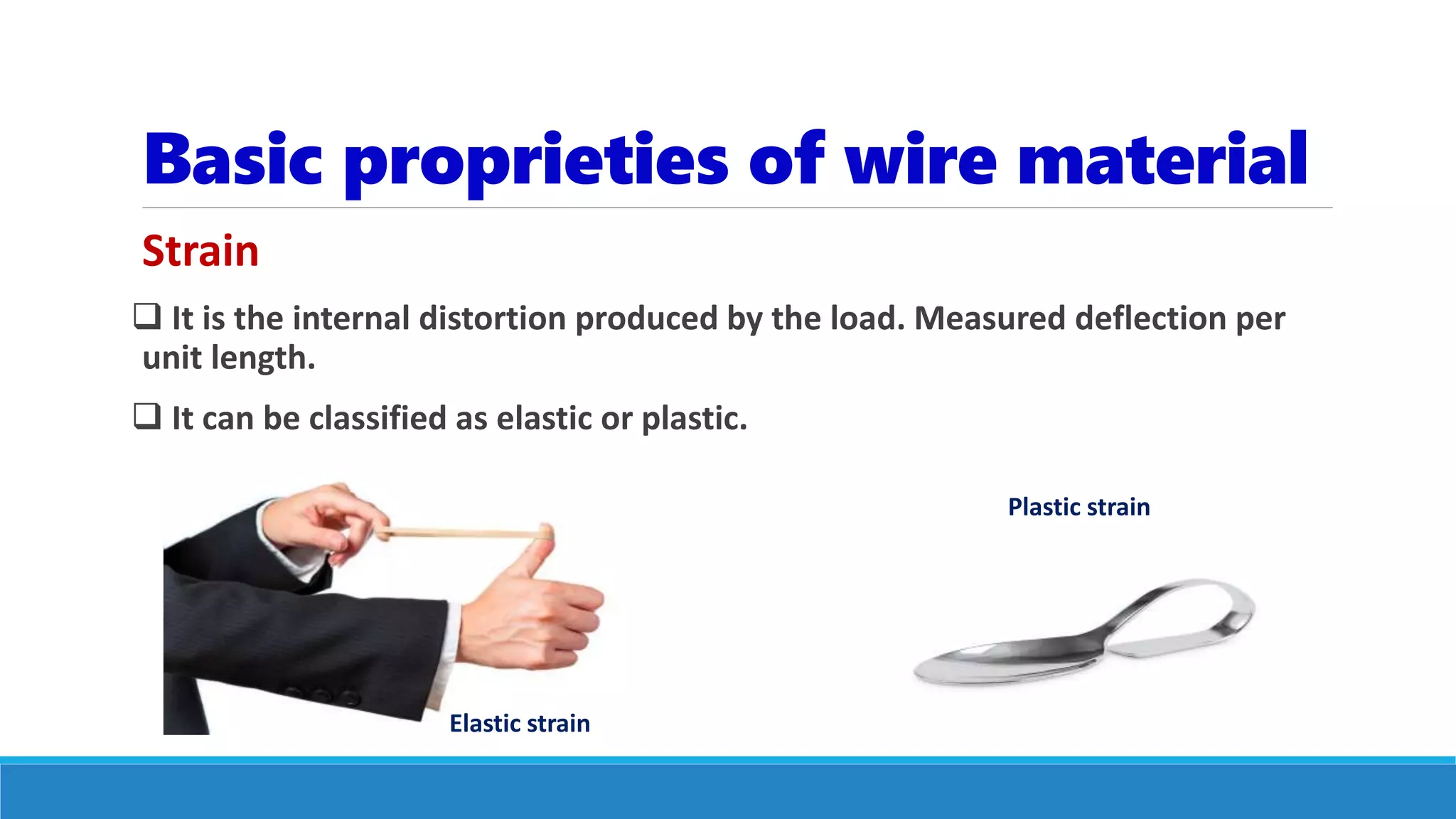

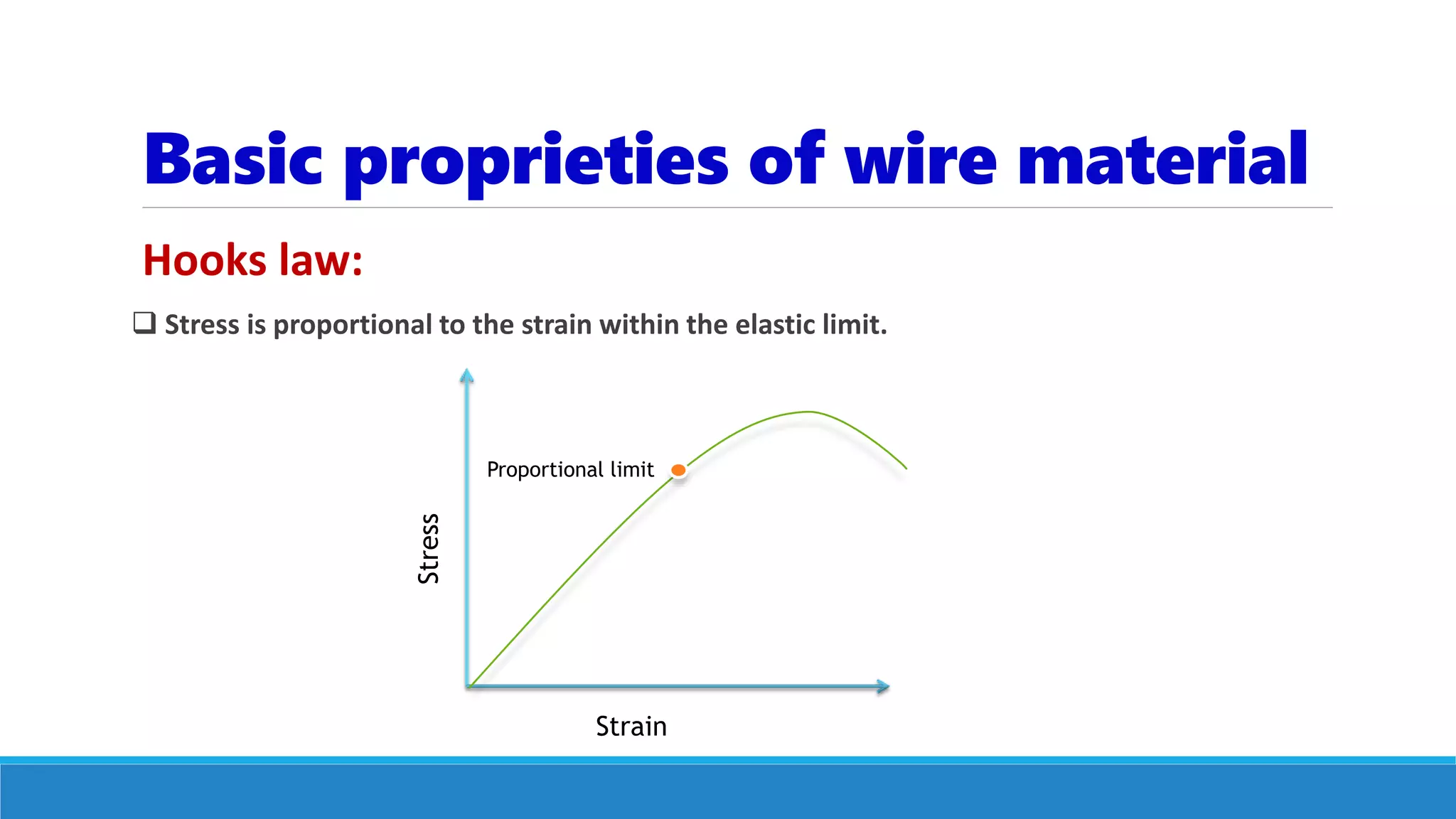

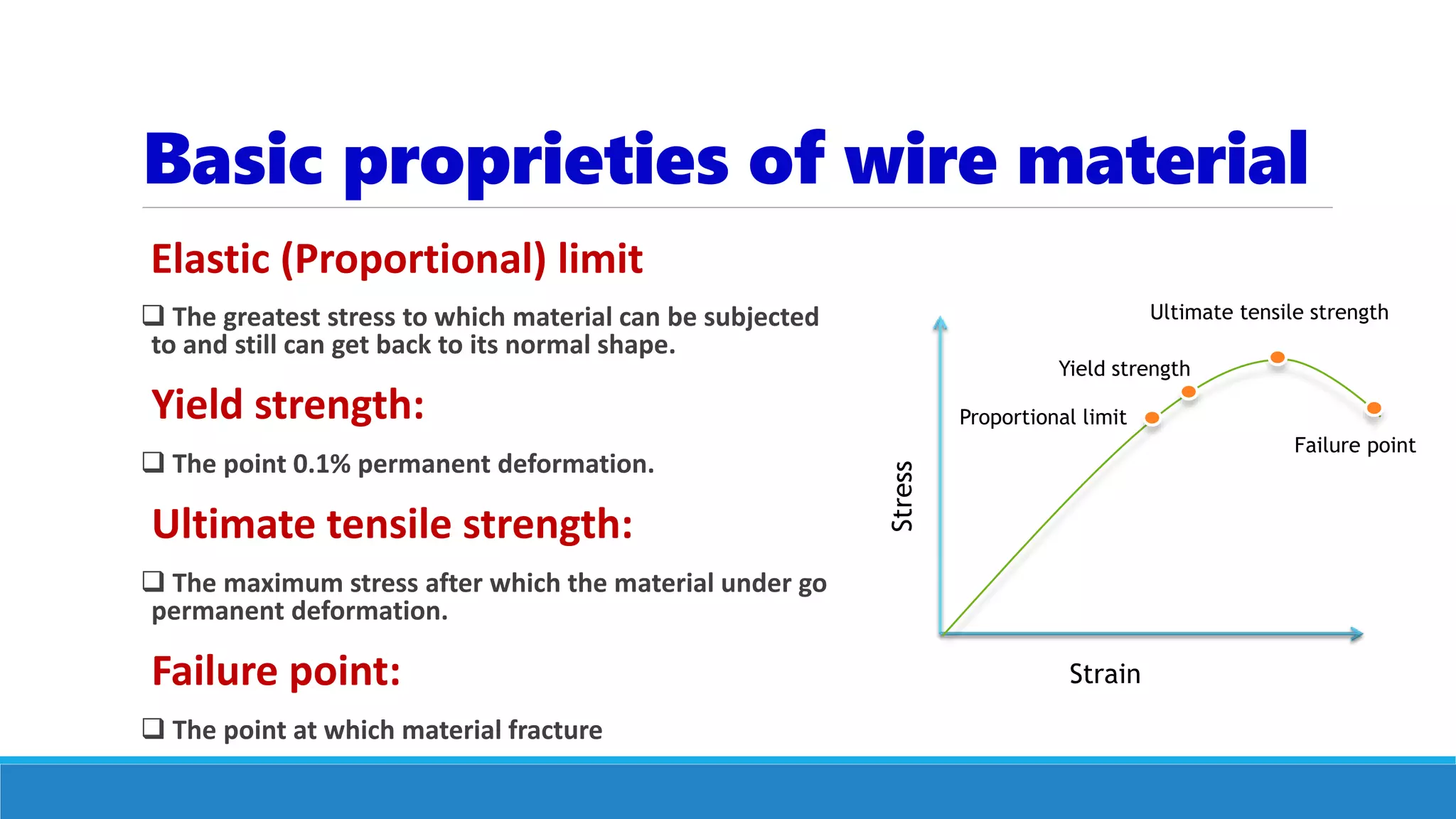

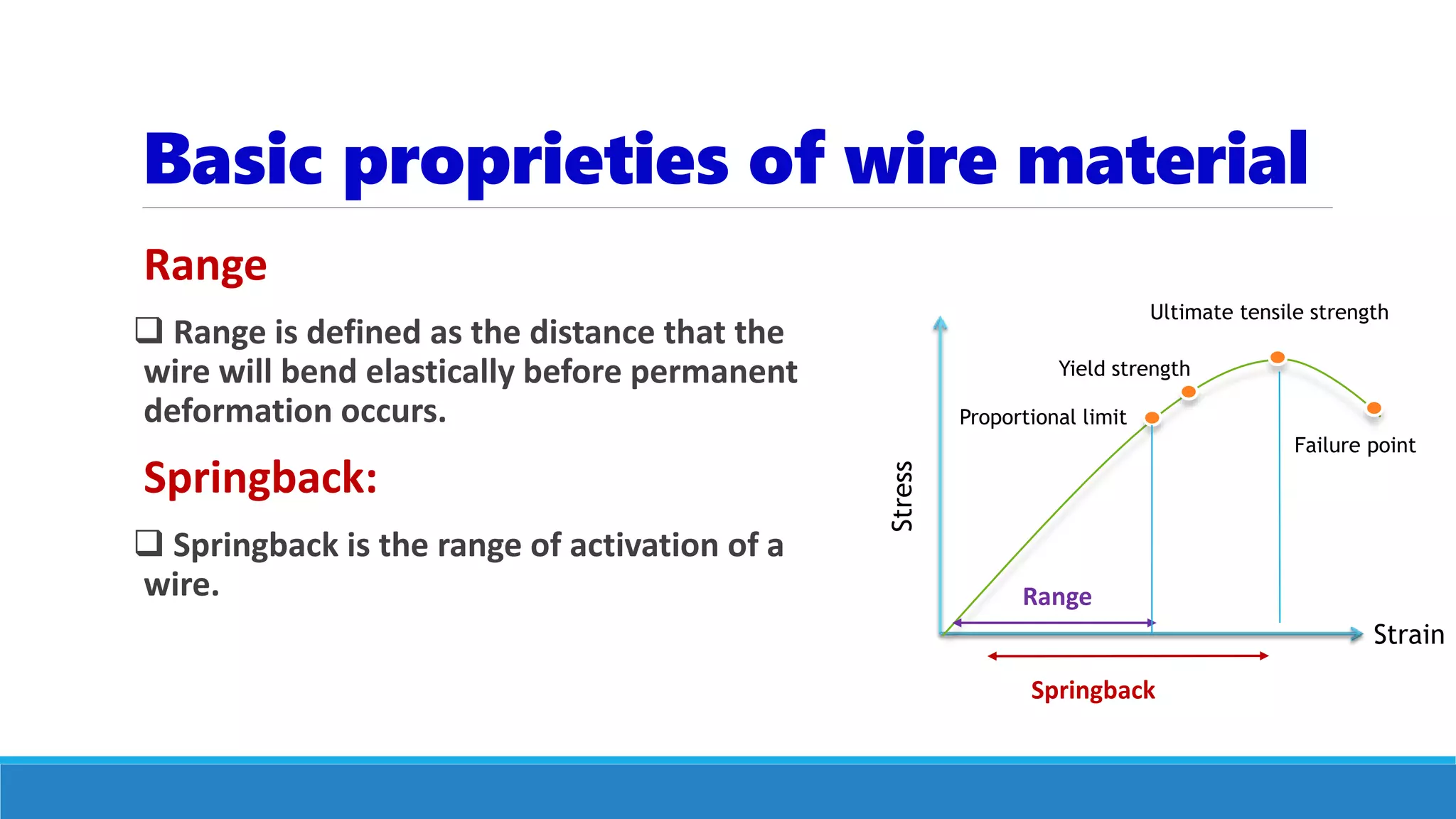

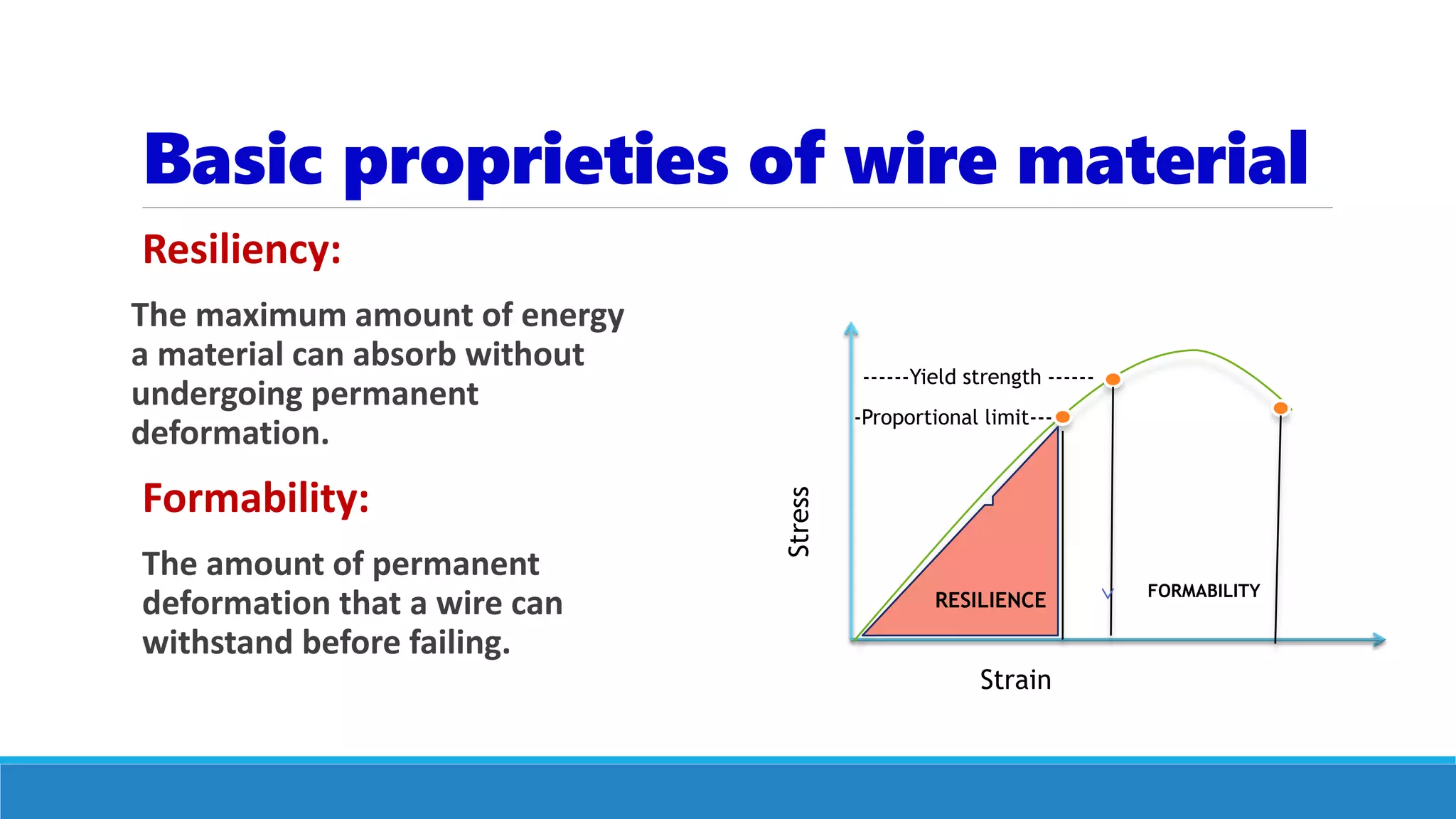

1. The basic definitions of mechanics, stress, strain, stiffness, strength and other mechanical properties relevant to orthodontic tooth movement.

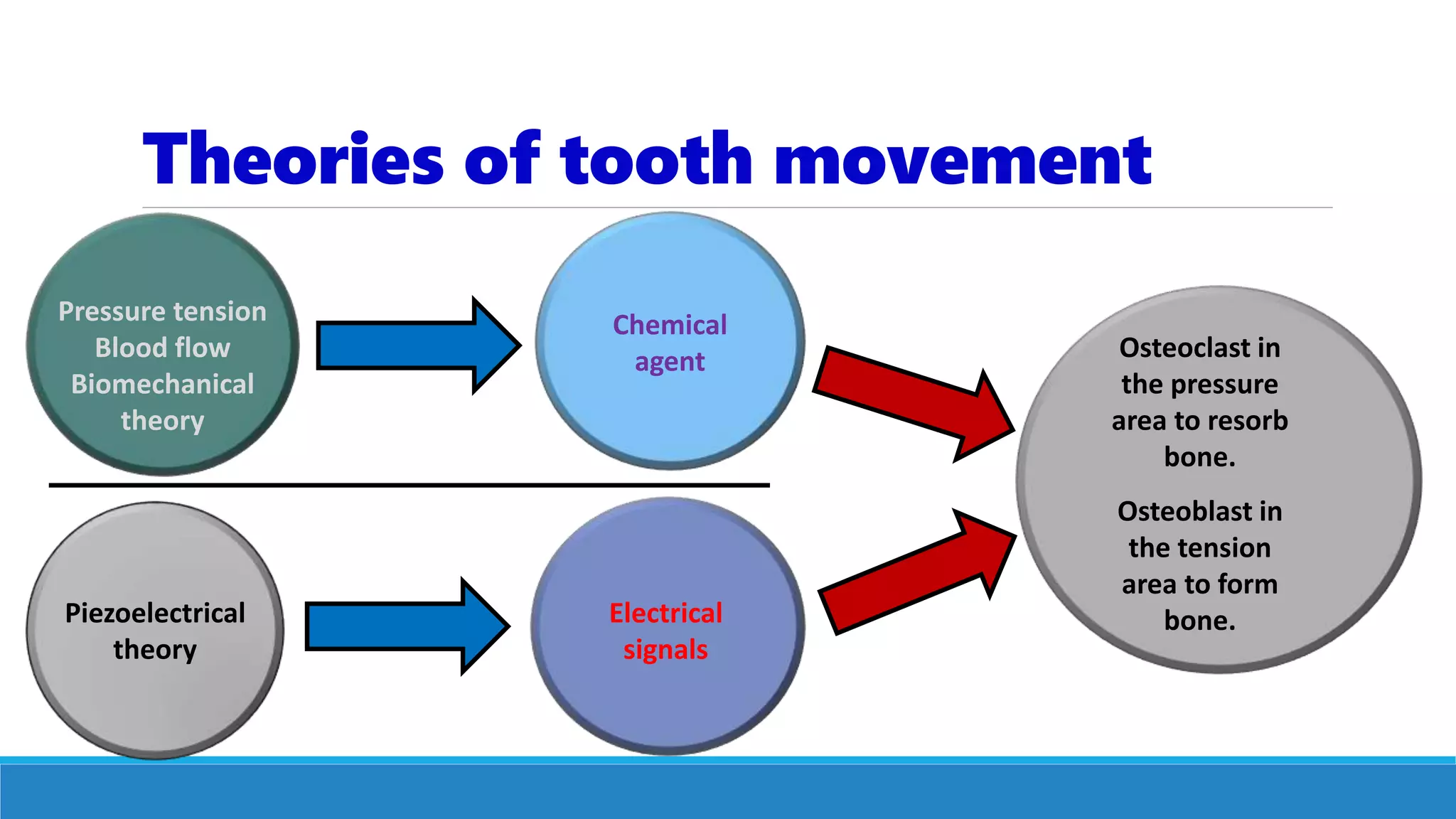

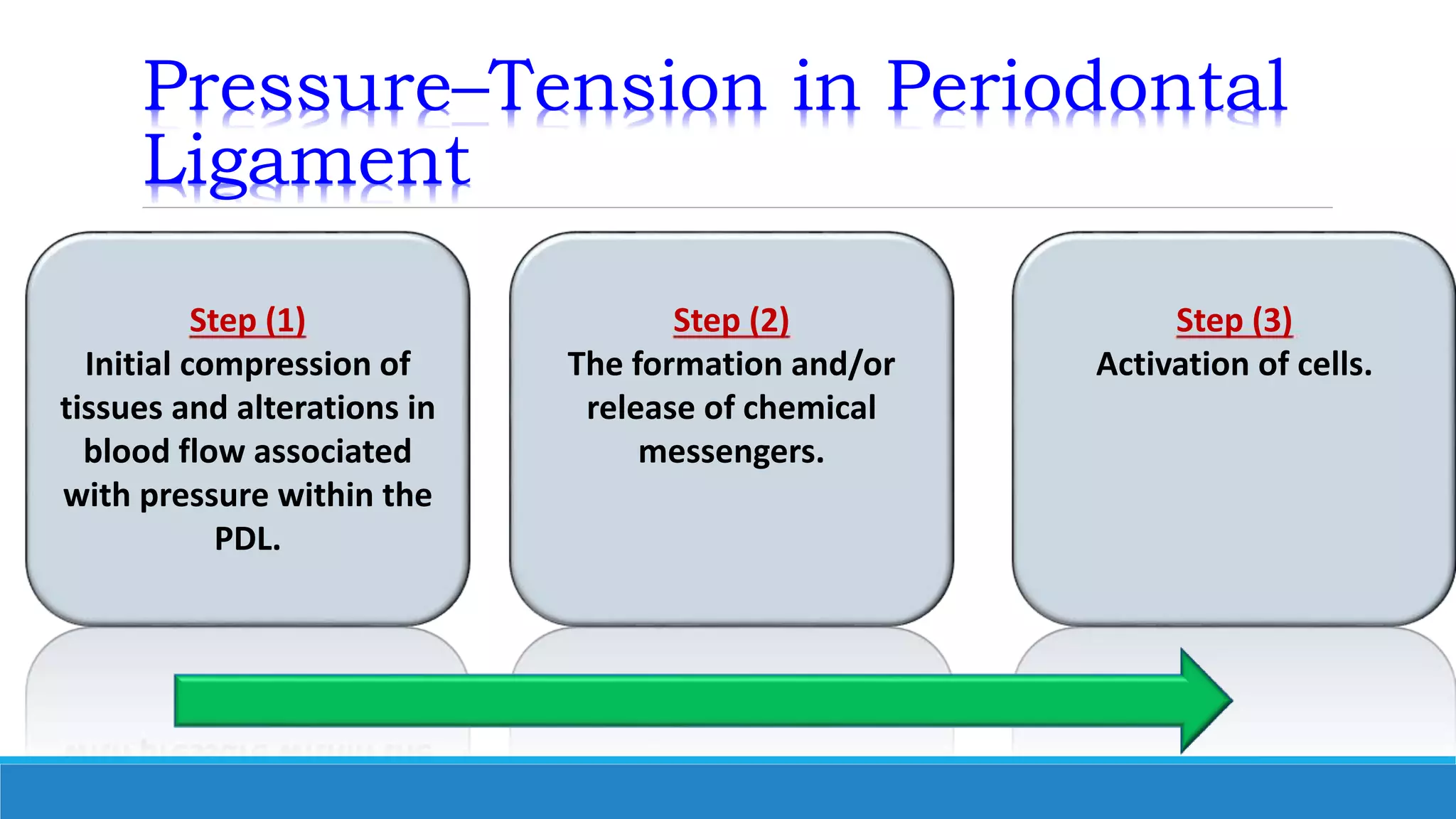

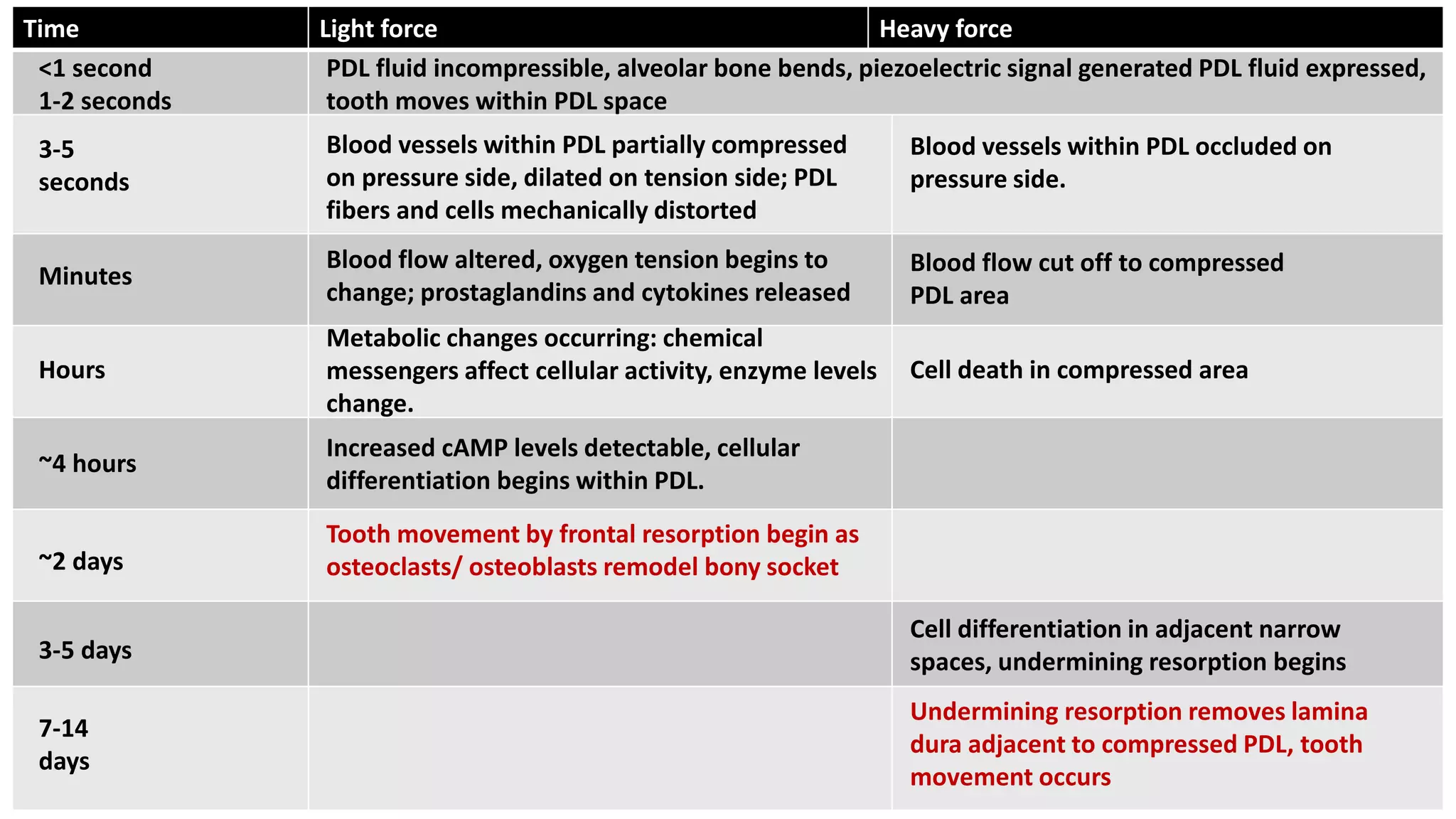

2. Theories of tooth movement including biomechanical, pressure-tension, fluid dynamics and piezoelectric theories.

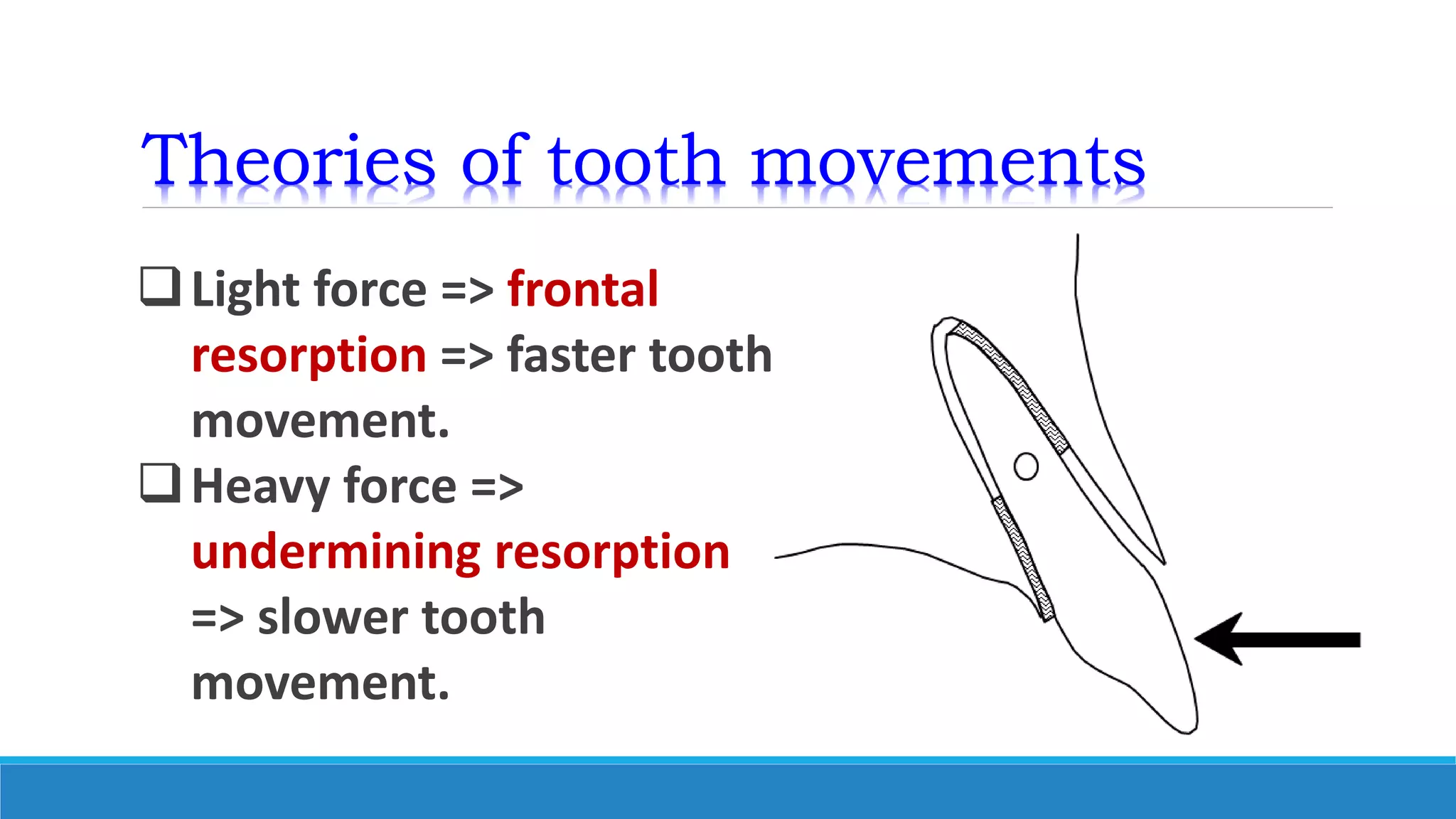

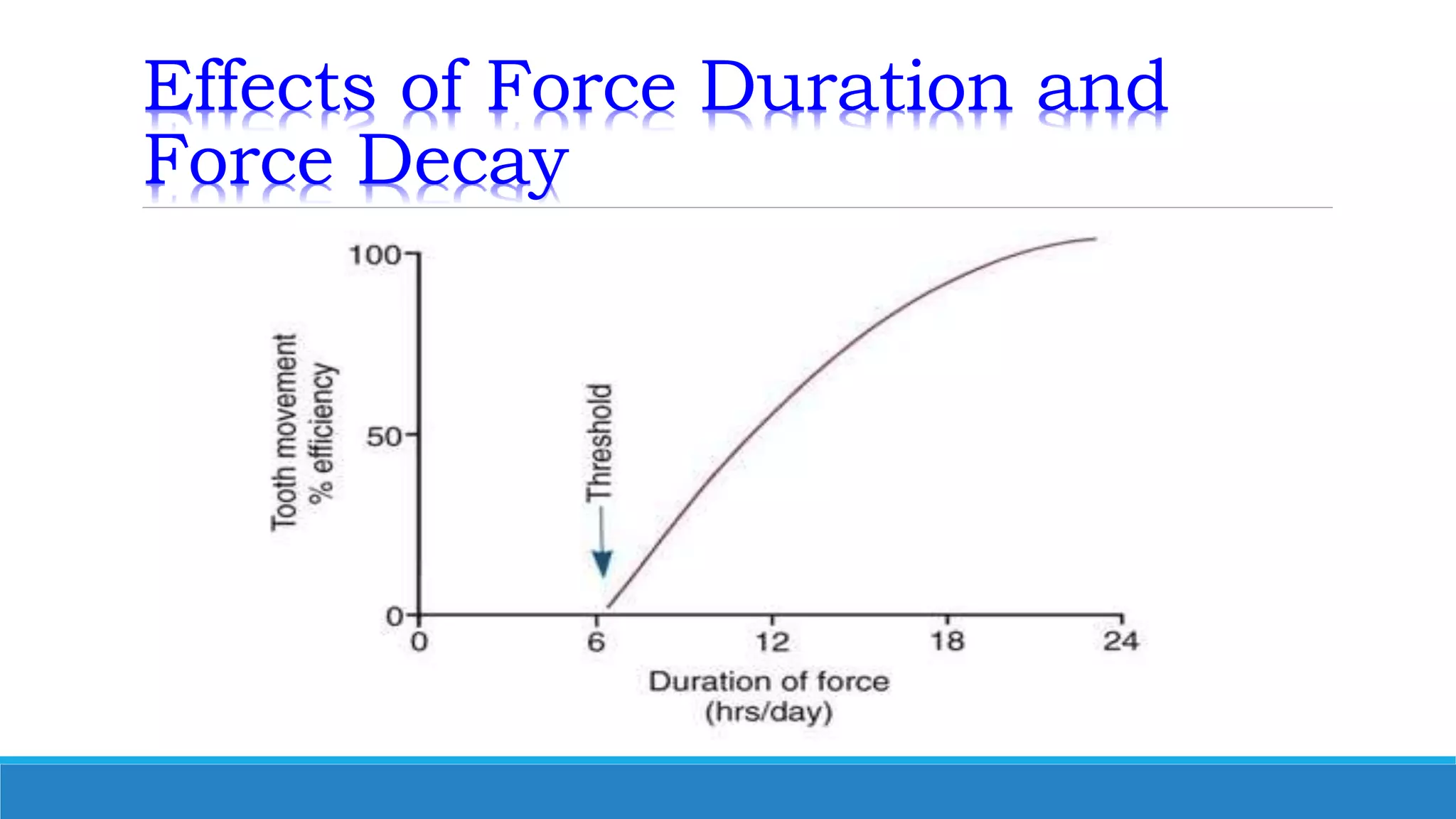

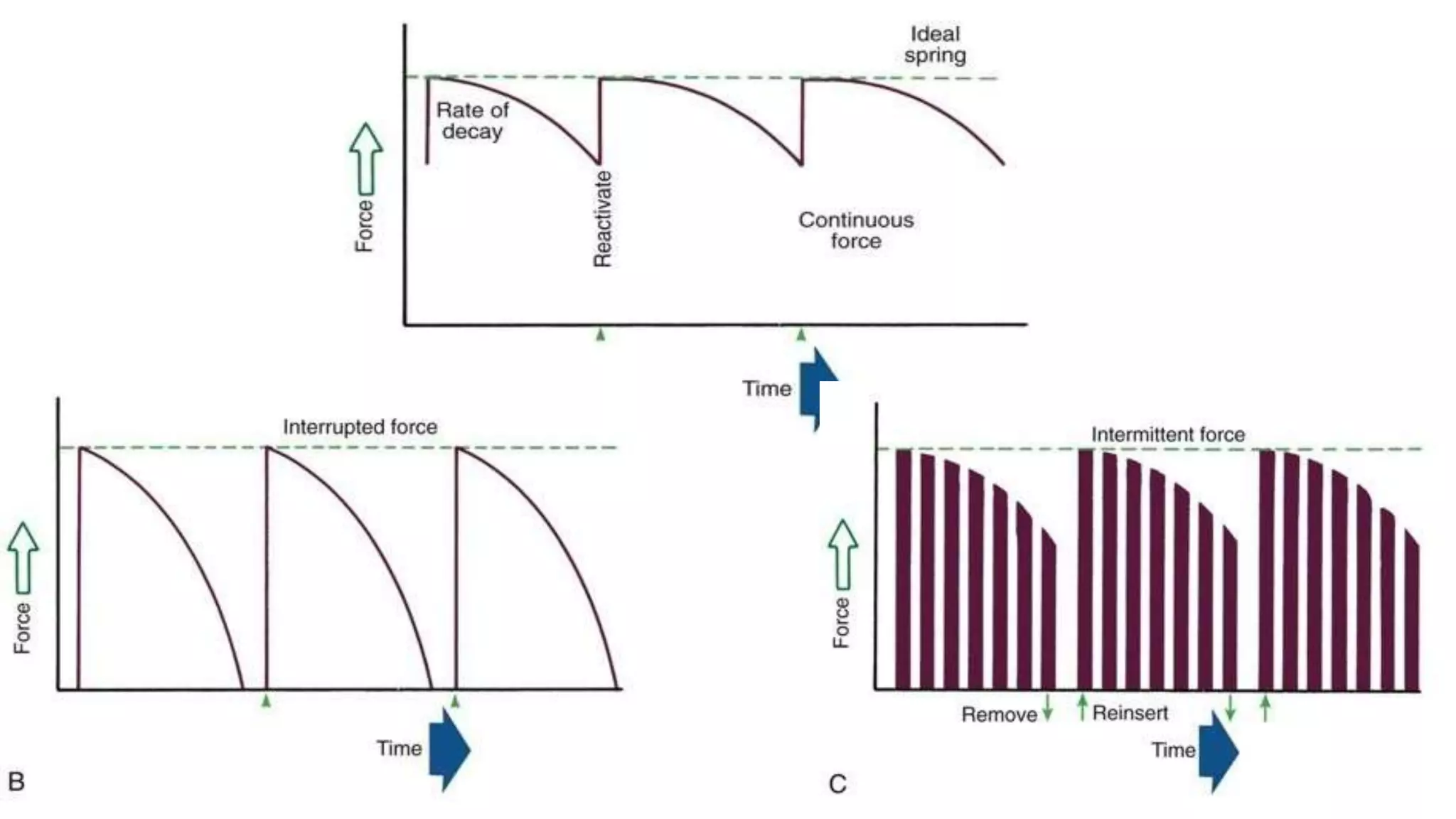

3. Factors that influence tooth movement including force magnitude, duration, and decay over time. Light continuous forces produce faster movement through bone remodeling compared to heavy forces which cause bone necrosis.

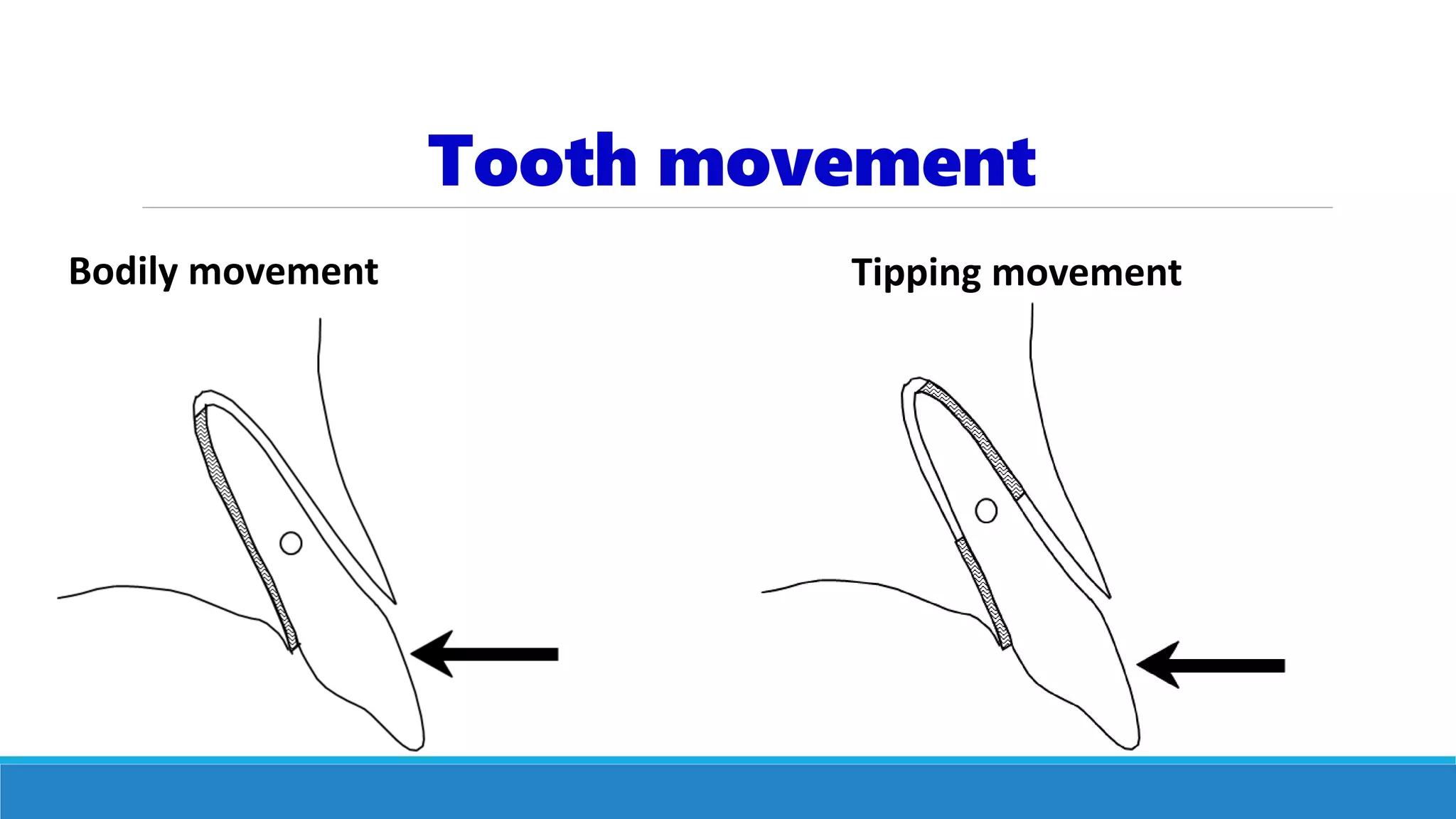

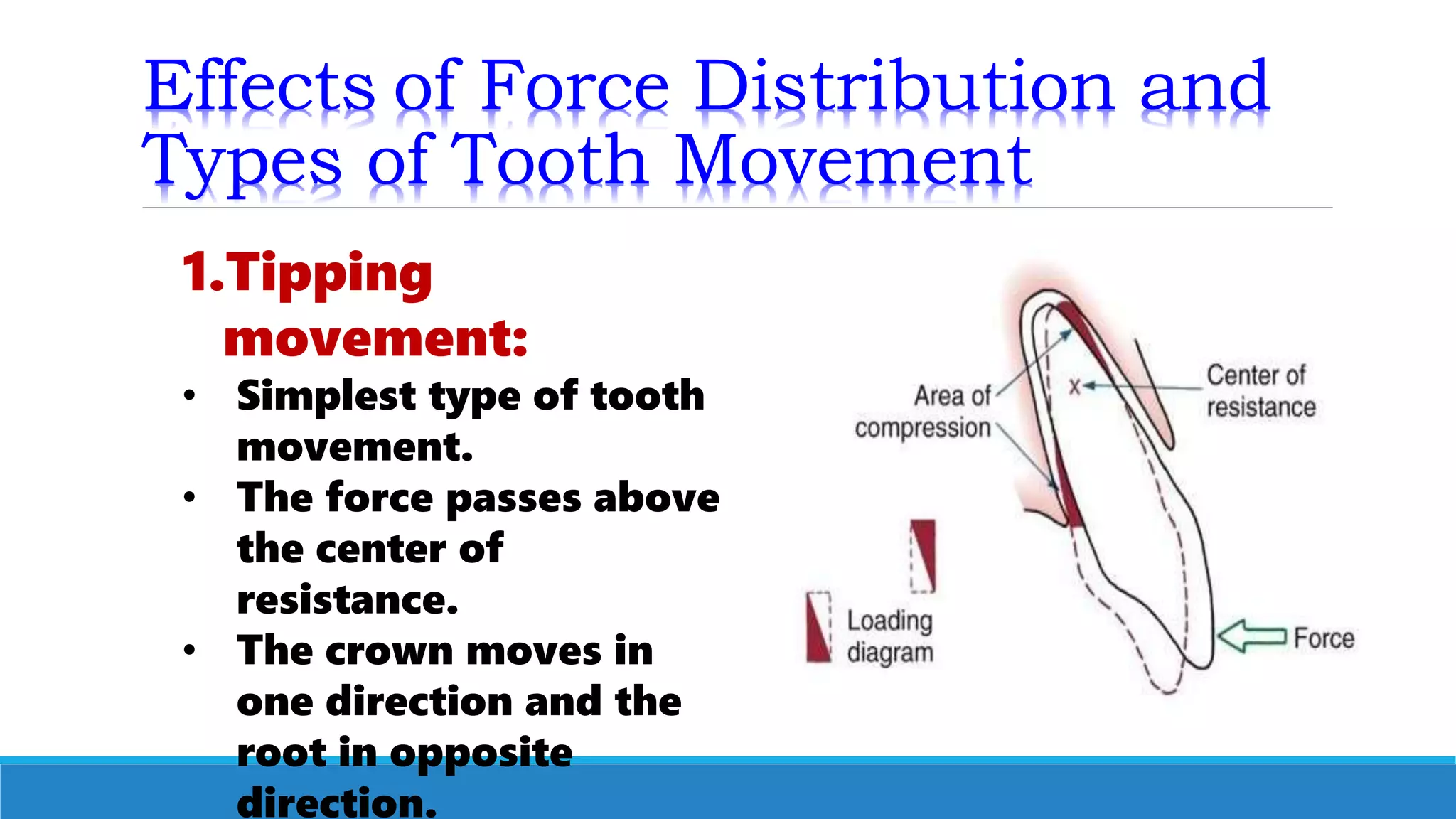

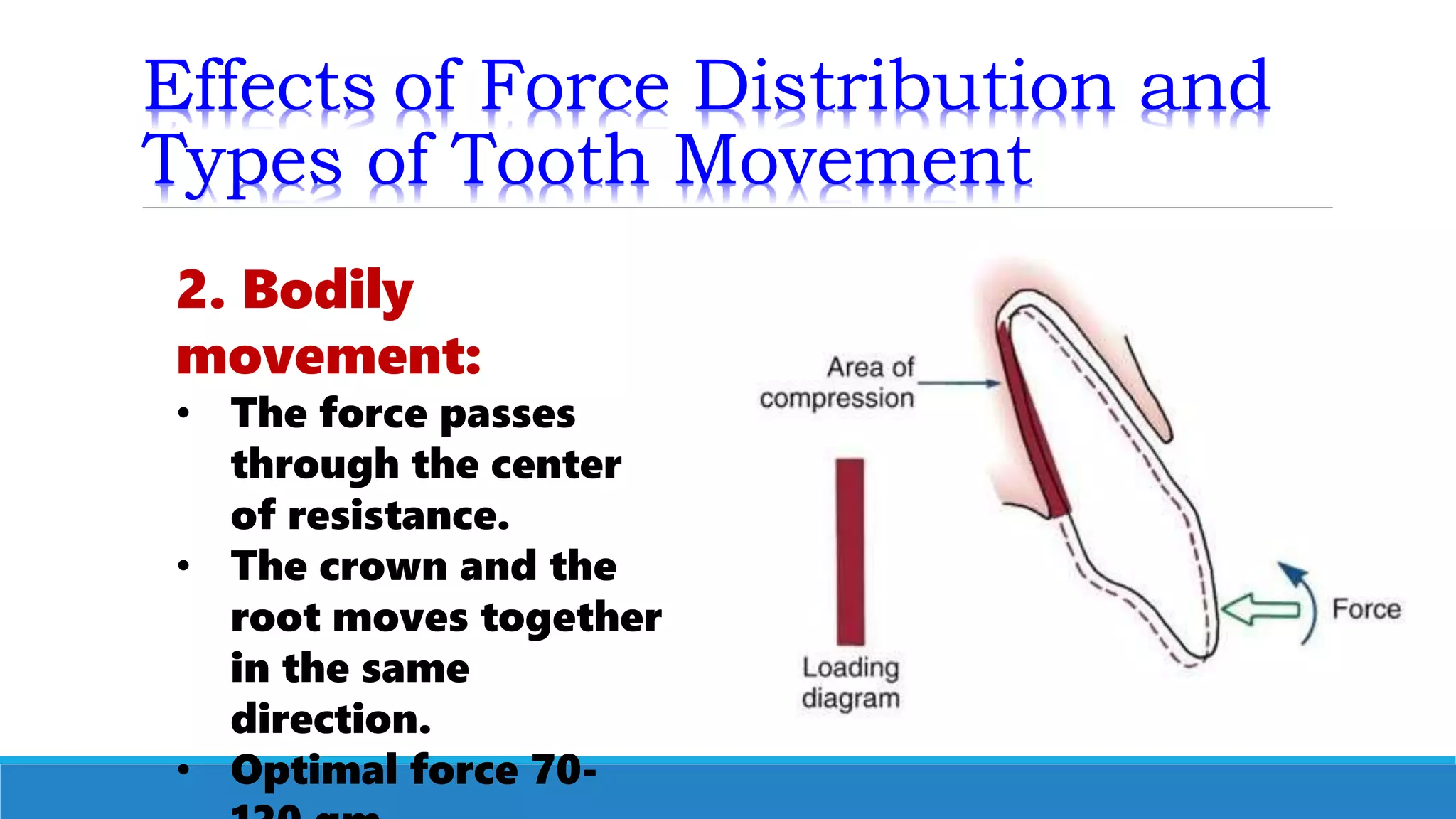

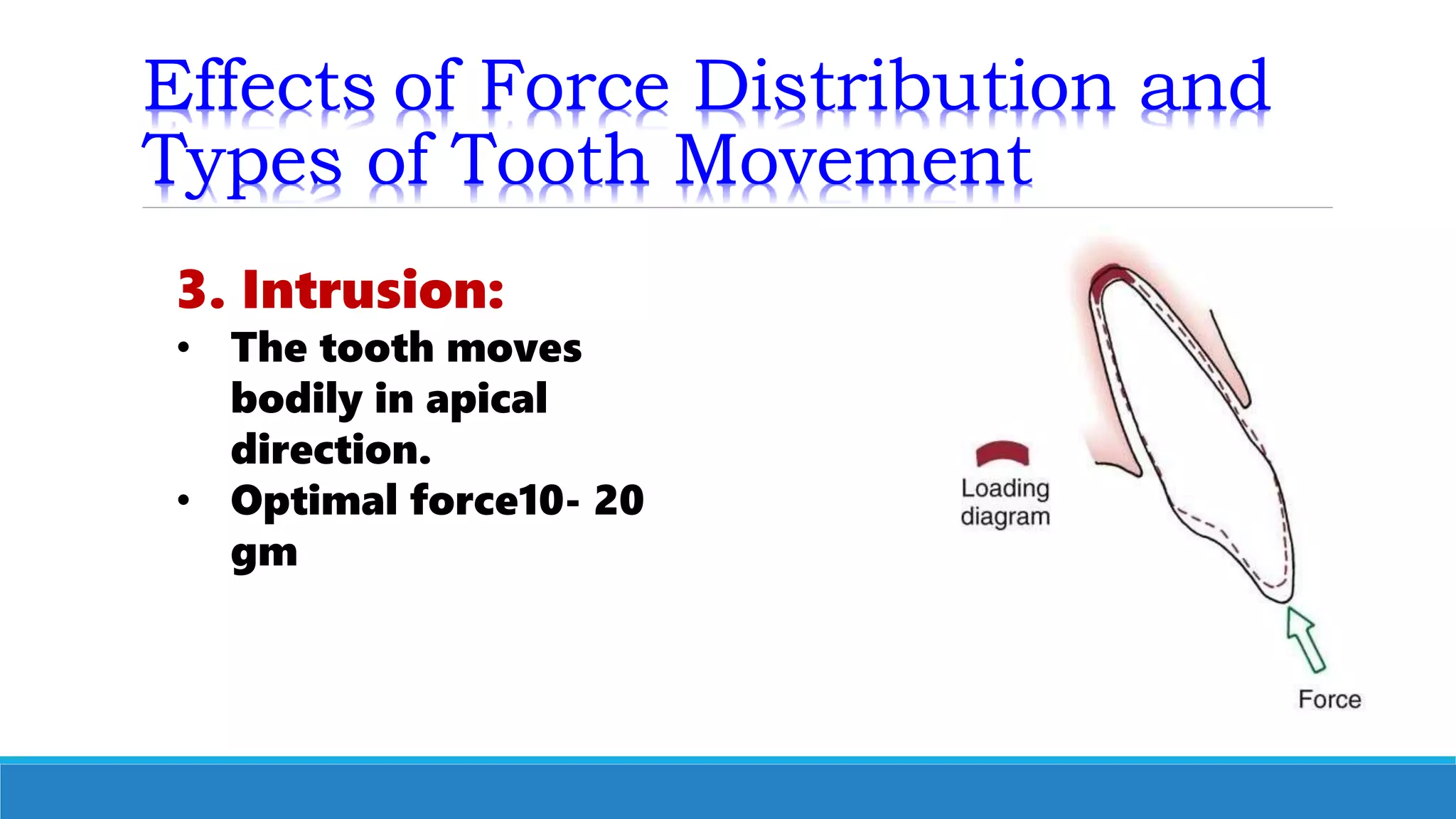

4. Types of tooth movement including tipping, bodily movement, intrusion, extrusion, rotation and root uprighting.