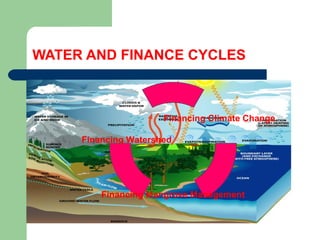

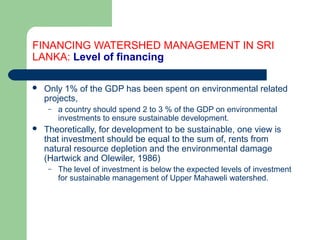

This document proposes a conceptual framework for a national policy on financing watershed management in Sri Lanka. It discusses several key points, including the need to consider both demand and supply of financing at each node of the water cycle. Currently, watershed management in Sri Lanka is underfunded and heavily reliant on intermittent foreign financing. The framework argues for securing national financing and allocating public funds earmarked for watershed management from the central government to provincial authorities. Generating provincial-level financing mechanisms and improving efficiency are also recommended.