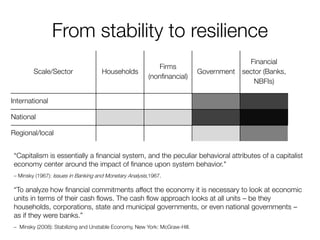

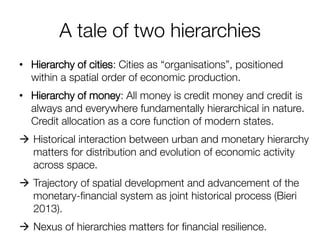

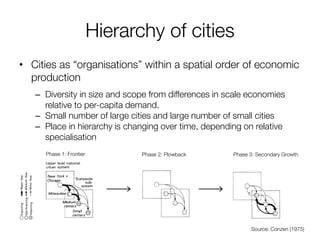

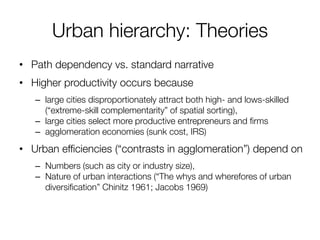

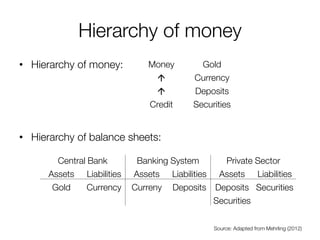

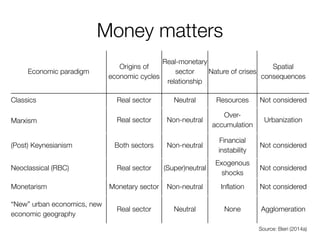

The document explores the concept of financial resilience, examining its relationship to both the financial and real sectors, and the policy tools necessary for achieving it. It discusses various definitions and theories of financial stability, the hierarchy of money, and the historical context of financial crises, particularly in relation to urban dynamics like those in Detroit. The interplay between financial systems and urban development is emphasized, showcasing the need for a macroprudential approach to regulate the interconnectedness of financial and real economies.

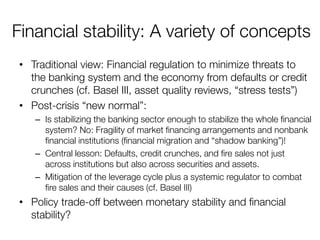

![Financial stability: A variety of concepts

•Different definitional scope:

–Systems definition: Financial stability = “well-functioning financial system” (role for monetary policy?)

–Narrow definition: (Excess) volatility of specific observable financial variable (asset price volatility, interest rate smoothness)

•Historical perspective:

–Volatility-based instability (ERM 1980s/1990s, 1987 crash, 1994 EME bond markets, 1998 Russian default, 2001 Argentinean default, 2007/08 US subprime crisis).

–Stress-based instability (Default of individual institution. Credit-Anstalt 1931, Guardian National Bank 1933, Bankhaus Herstatt 1974, BCCI 1991, Barings 1995, LTCM 1998, recent institutional failures [Northern Rock, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, AIG]).

–Crisis-based instability triggered by both real and financial sector imbalances.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/financialresiliencebierirffc14-141028140357-conversion-gate02/85/Conceptualizing-Financial-Resilience-8-320.jpg)