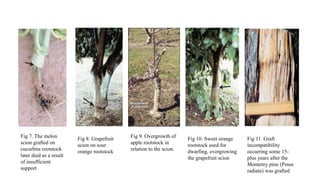

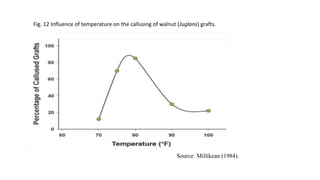

The document discusses various factors that affect the success of grafting and budding in horticultural crops, including plant species compatibility, seasonal considerations, rootstock growth activity, craftsmanship, pests, and environmental conditions. It elaborates on the significance of maintaining polarity during grafting and highlights different propagation techniques that enhance success rates. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of factors such as temperature, humidity, moisture management, and the age of the scion and rootstock in achieving successful graft unions.