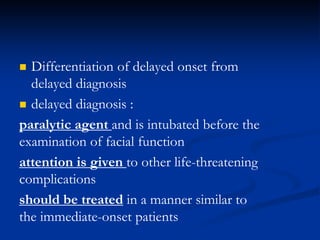

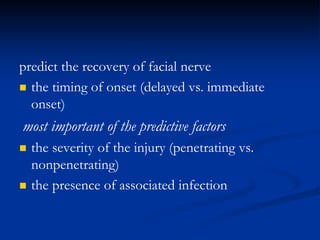

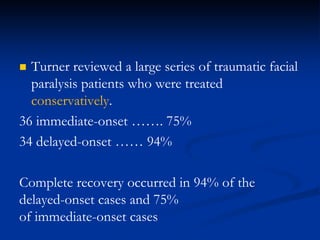

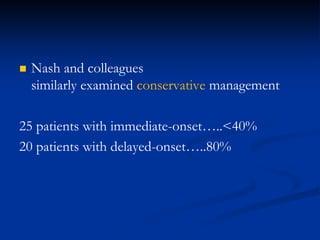

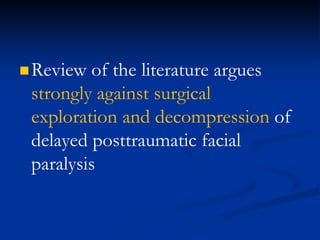

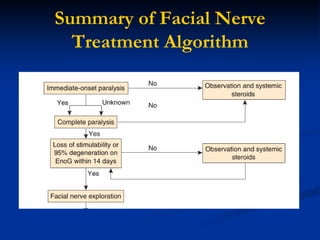

- Patients with delayed-onset facial paralysis from temporal bone fractures are generally treated conservatively with corticosteroids unless contraindicated.

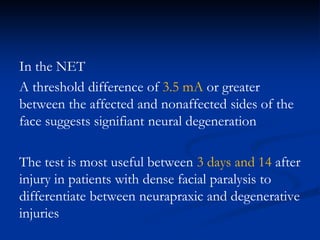

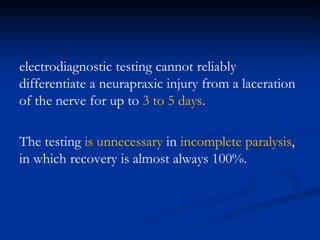

- Patients with immediate-onset complete paralysis undergo nerve stimulator testing between 3-7 days to determine if surgical exploration is needed.

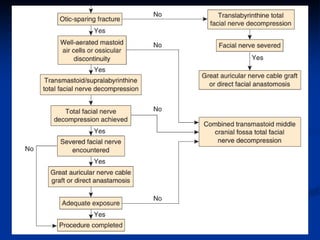

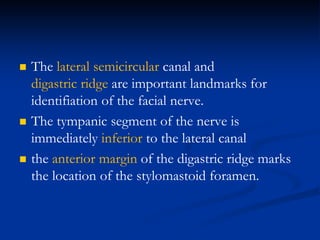

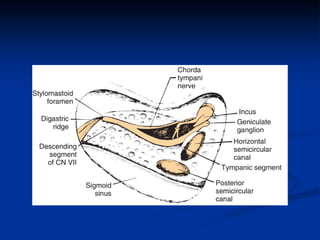

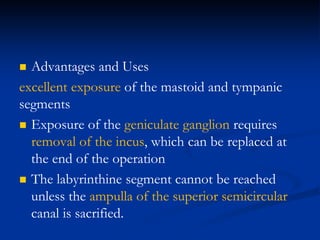

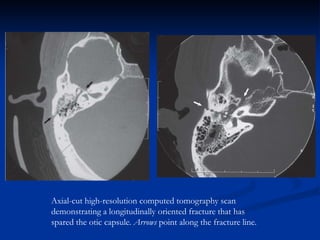

- Two surgical approaches are used for otic capsule-sparing fractures - transmastoid/supralabyrinthine or transmastoid/middle cranial fossa, depending on mastoid aeration and ability to fully decompress the nerve.

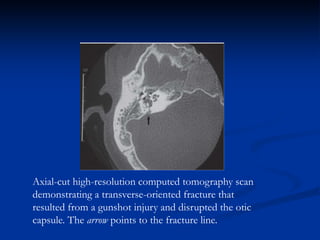

- Translabyrinthine approach is used for otic capsule-disrupting fractures to fully expose the facial nerve from geniculate ganglion to stylomastoid for