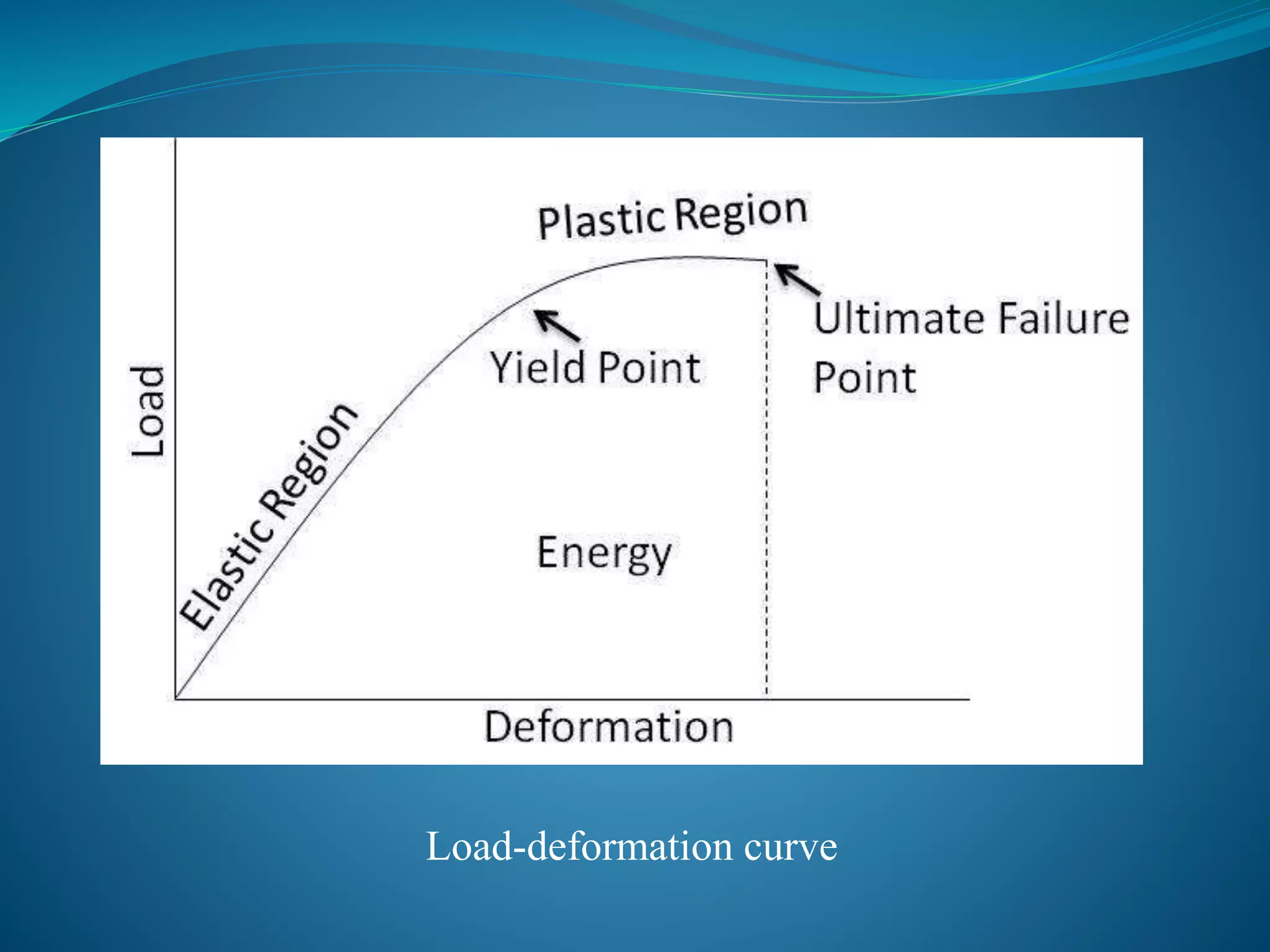

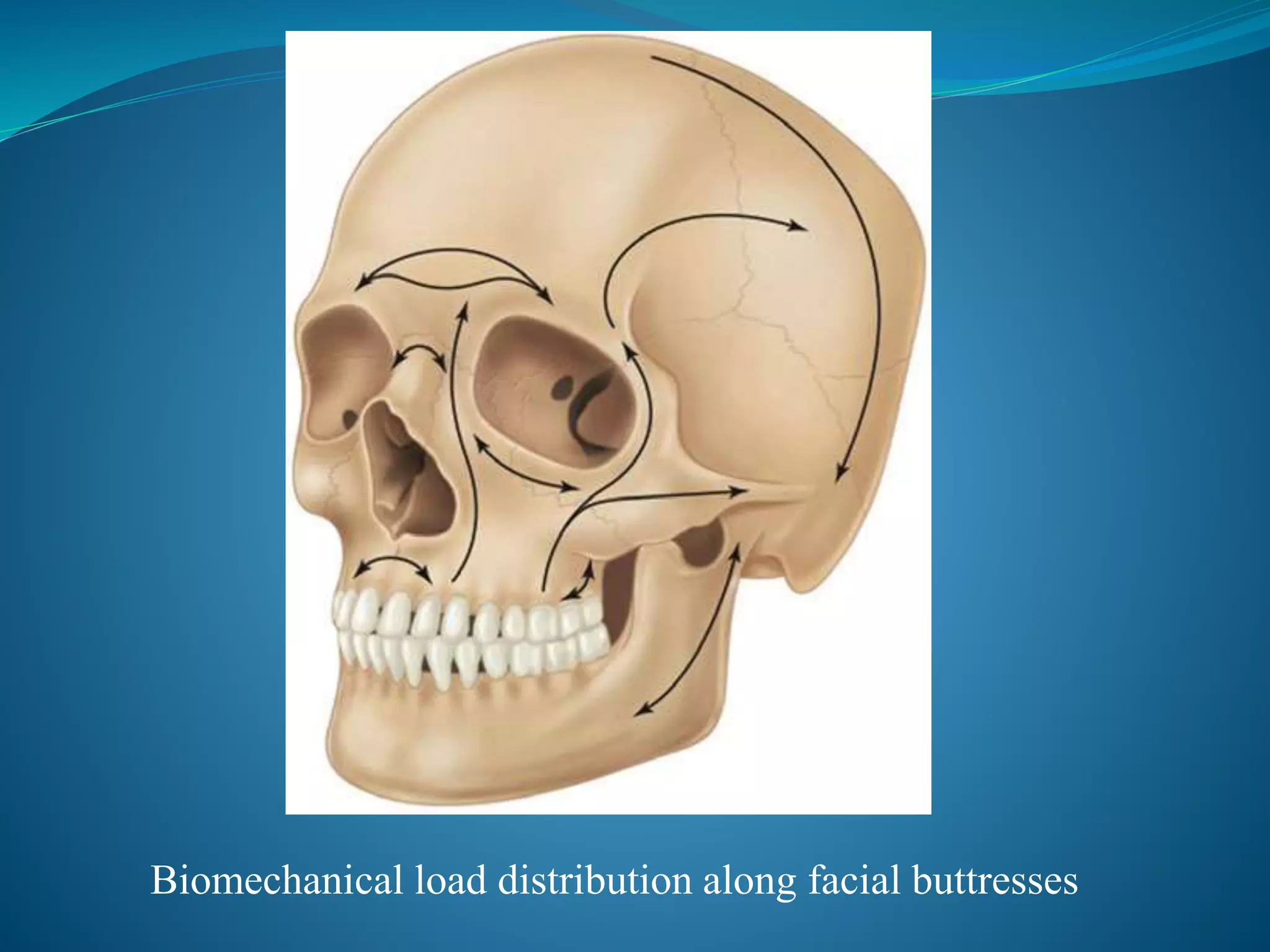

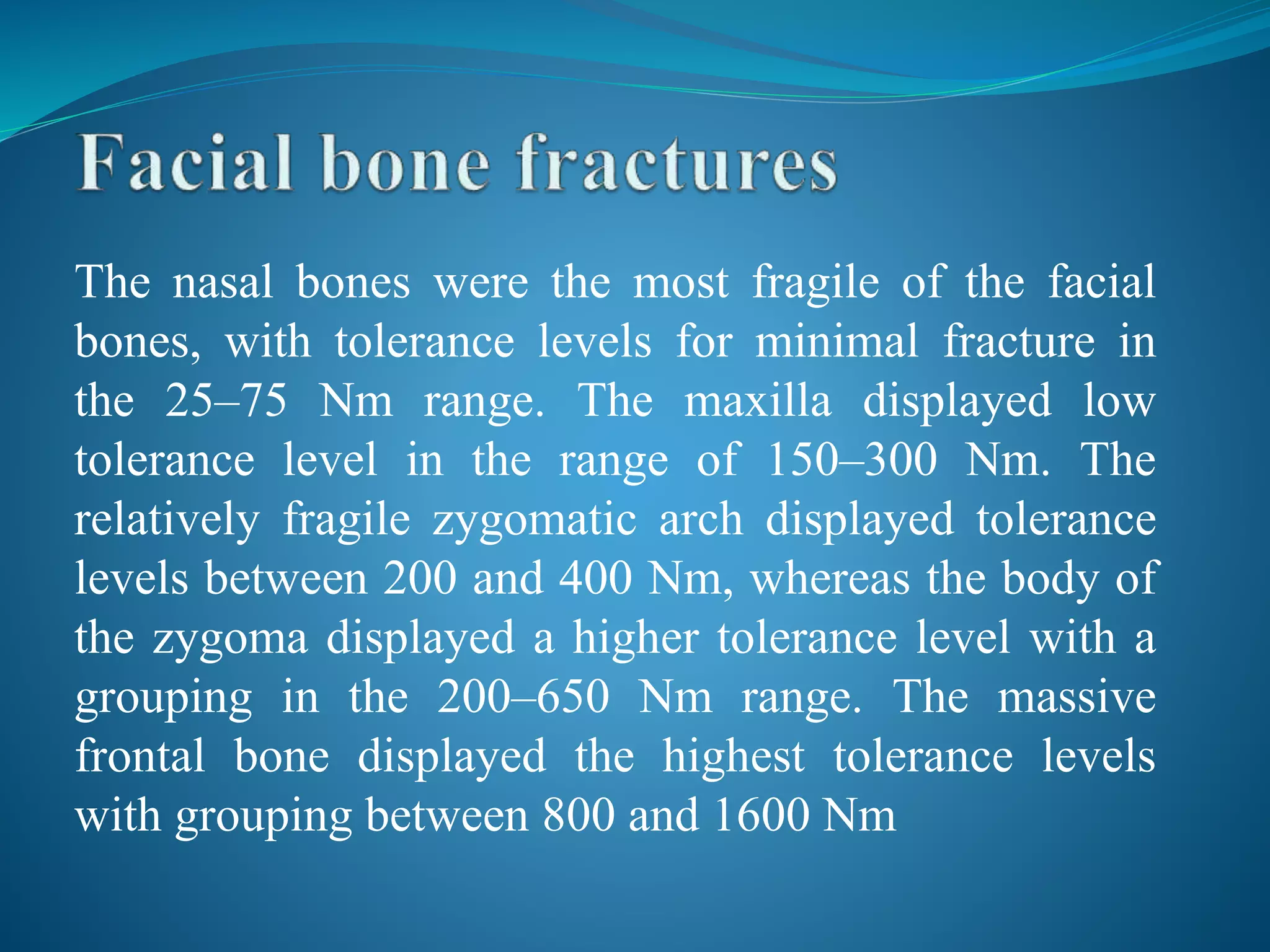

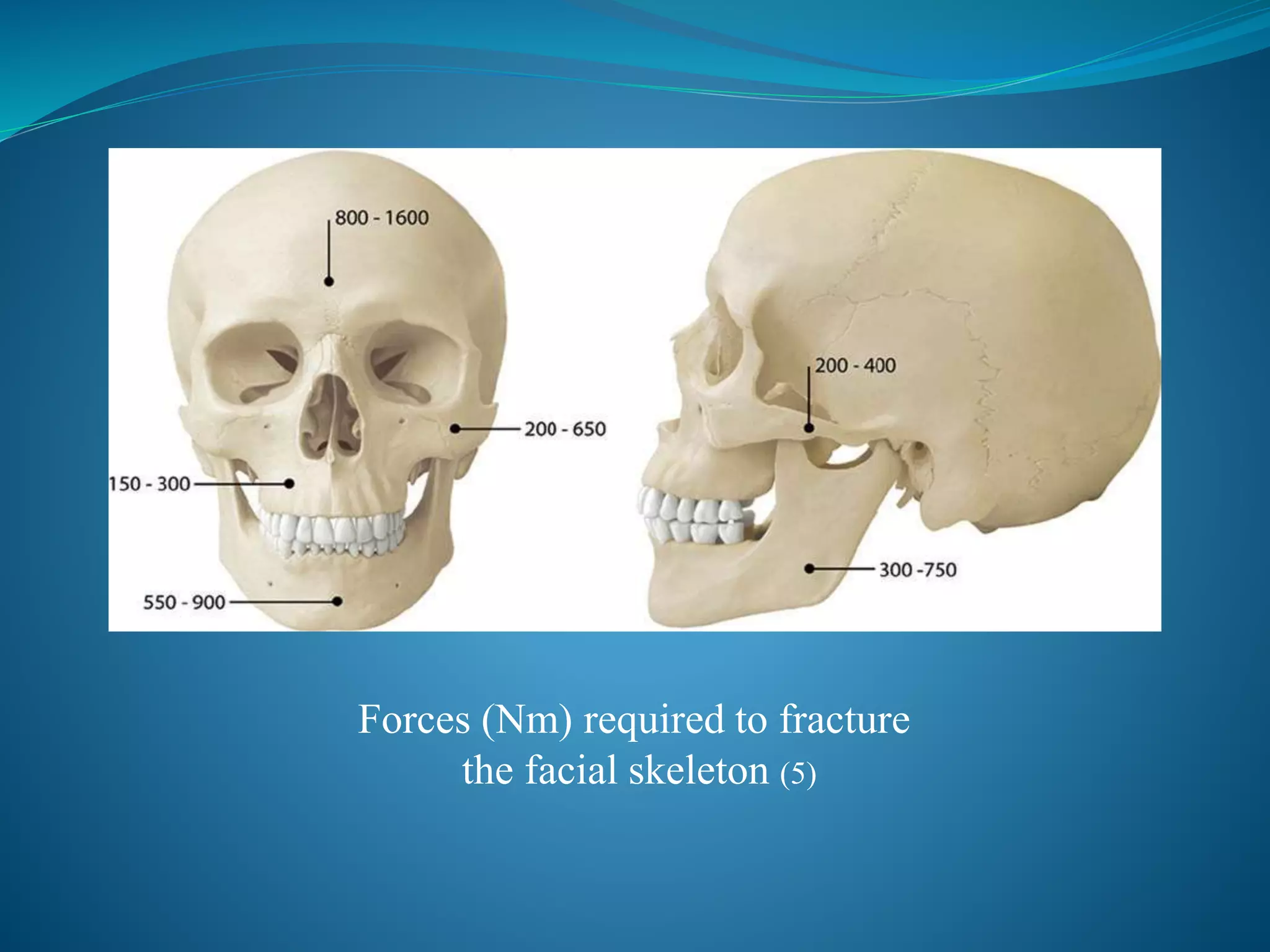

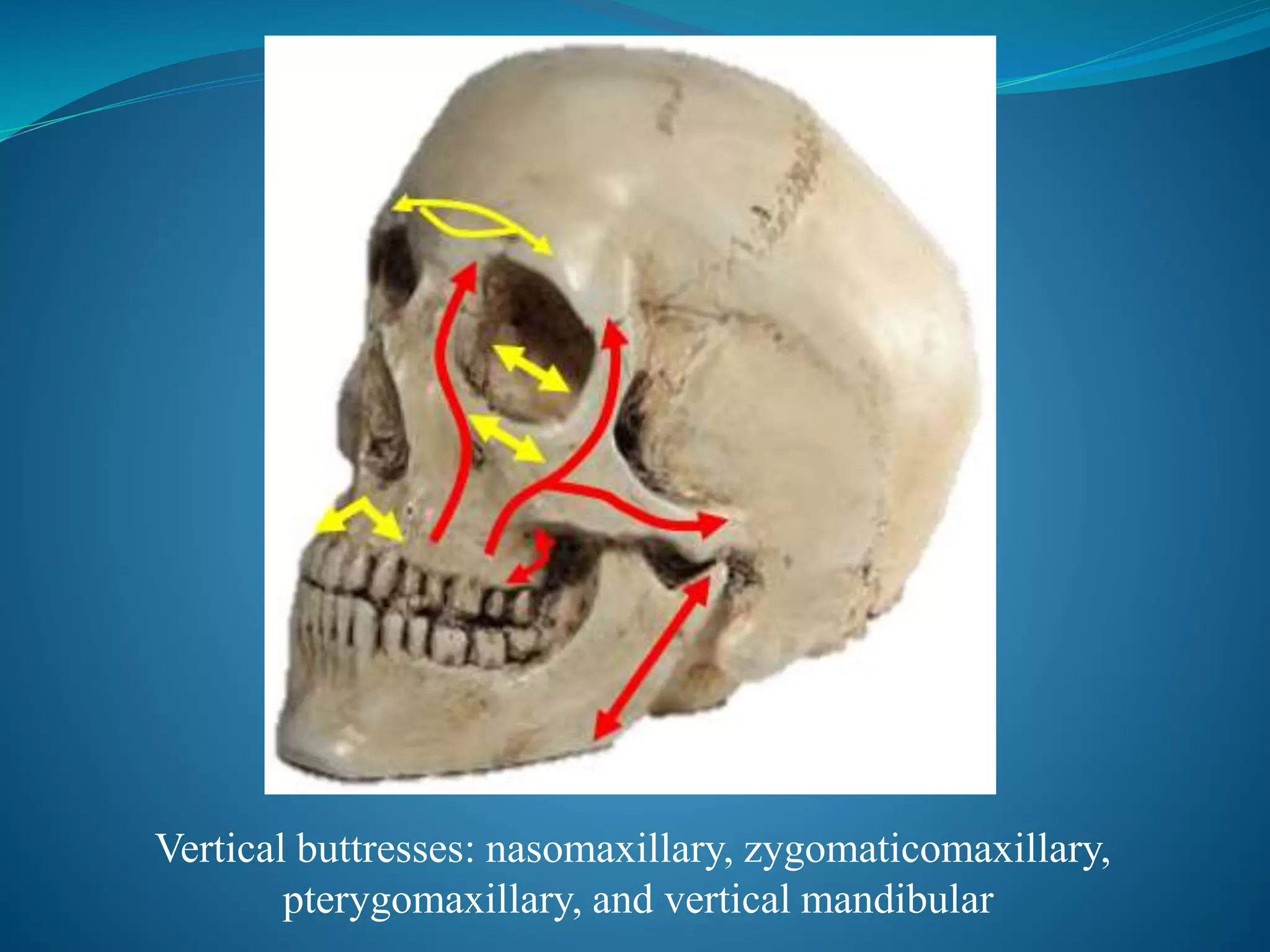

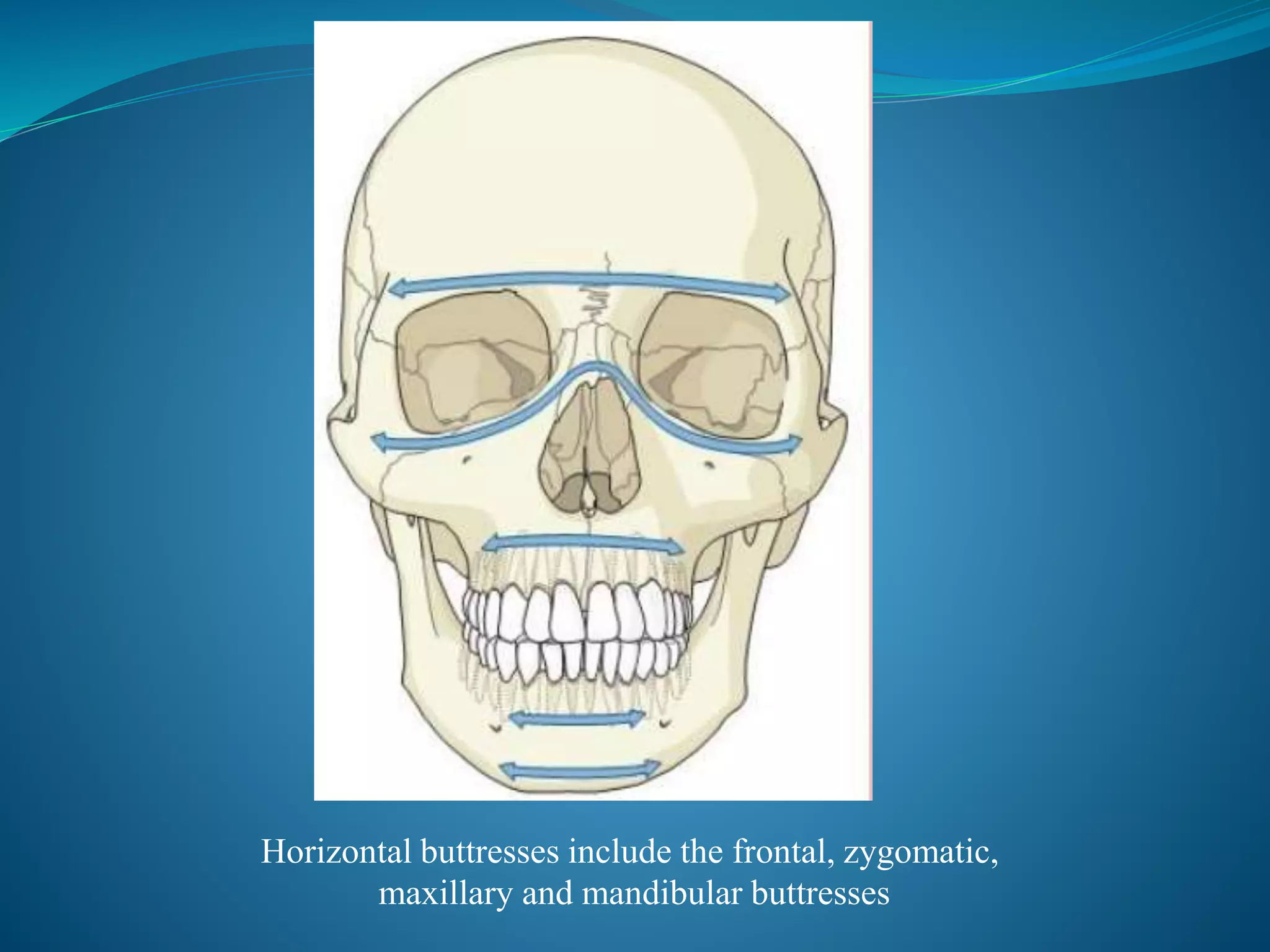

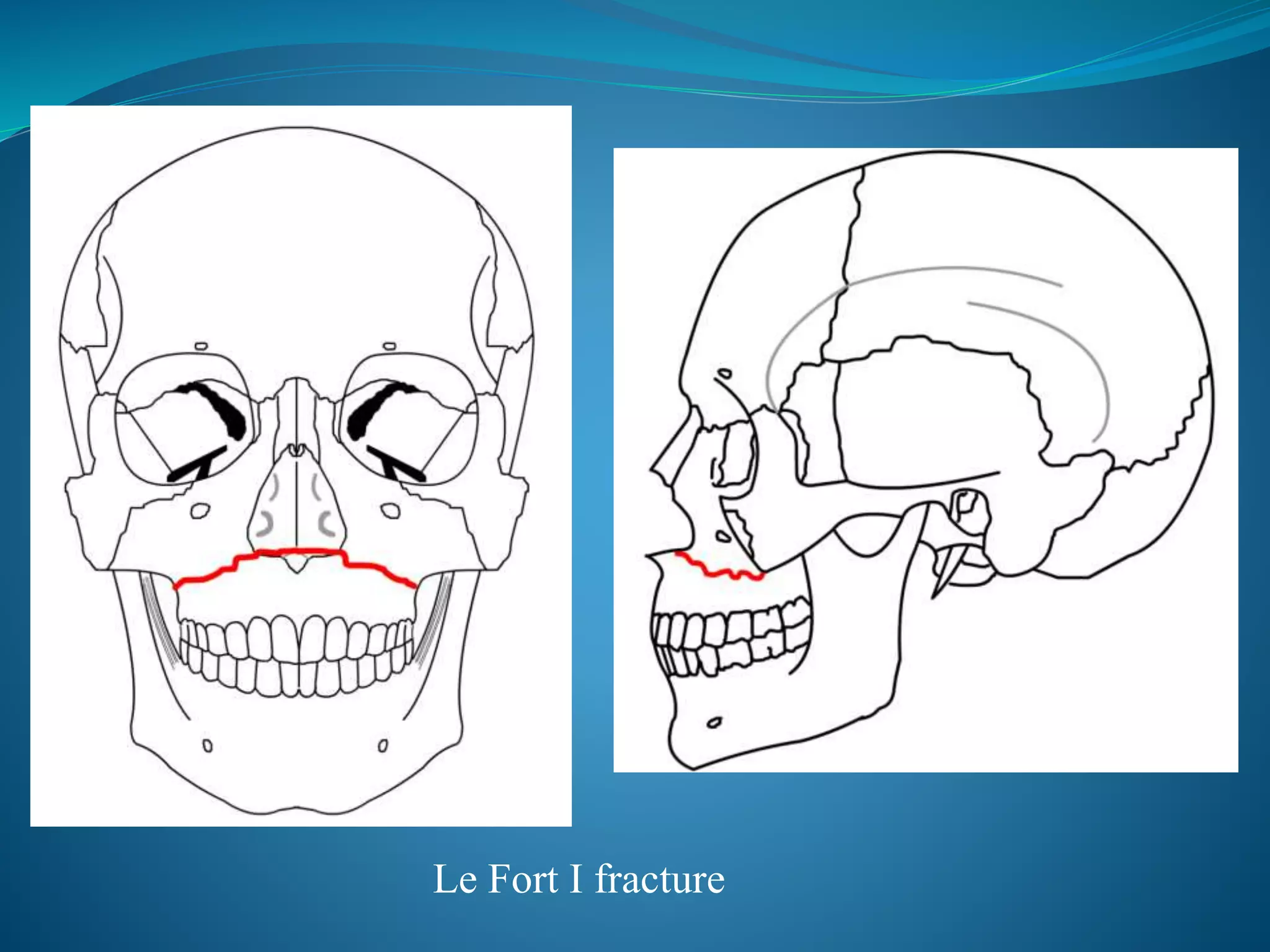

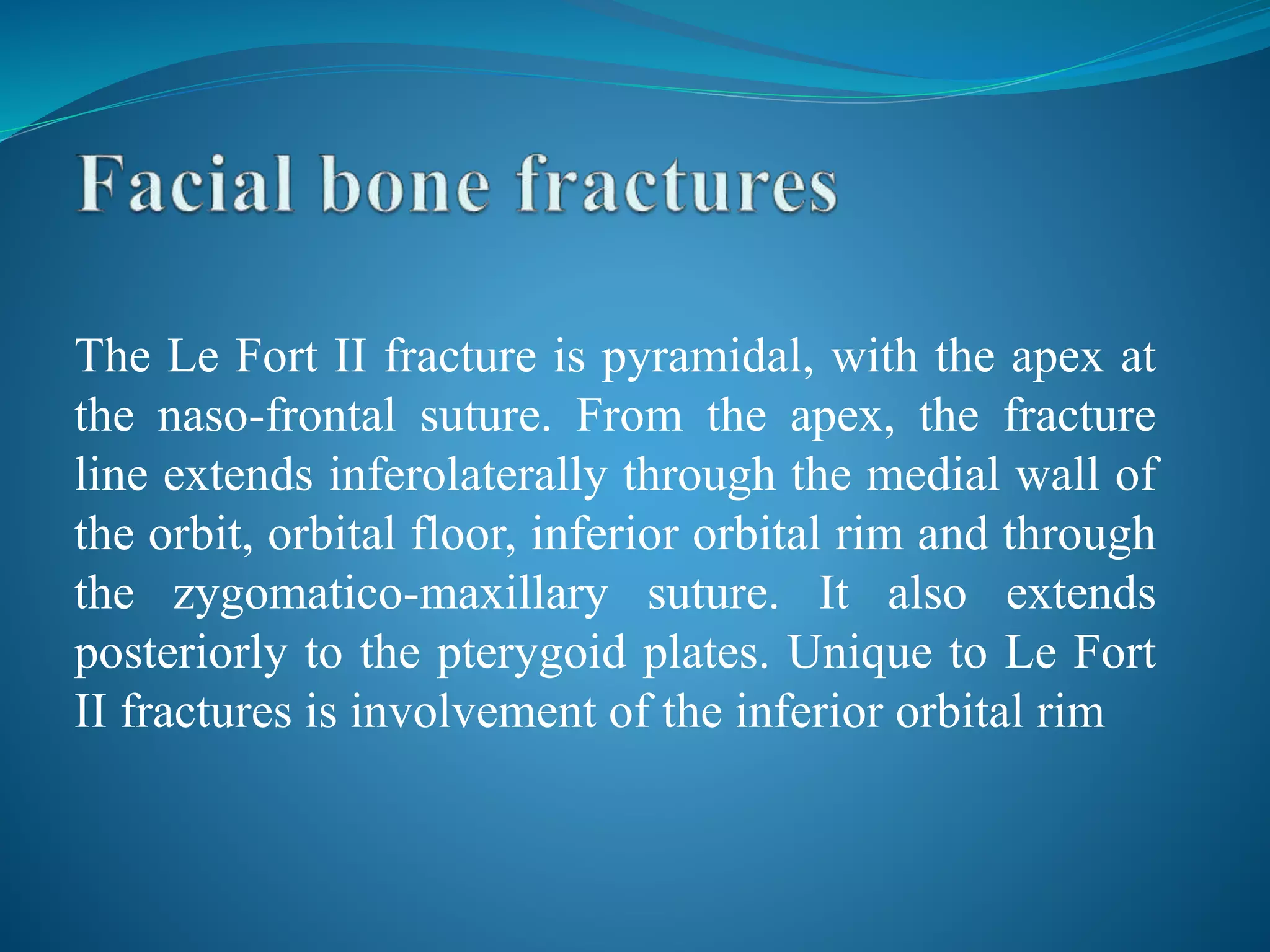

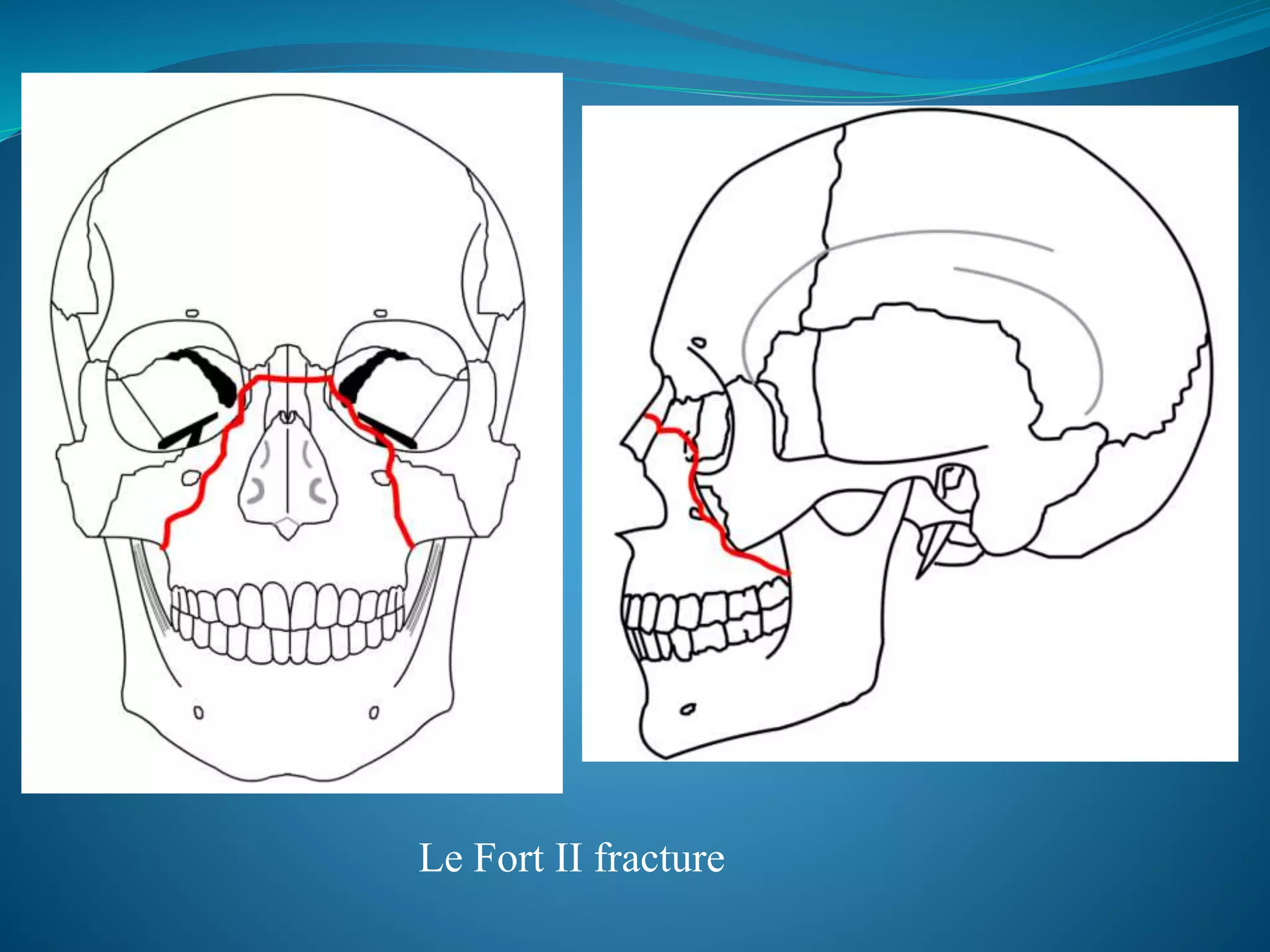

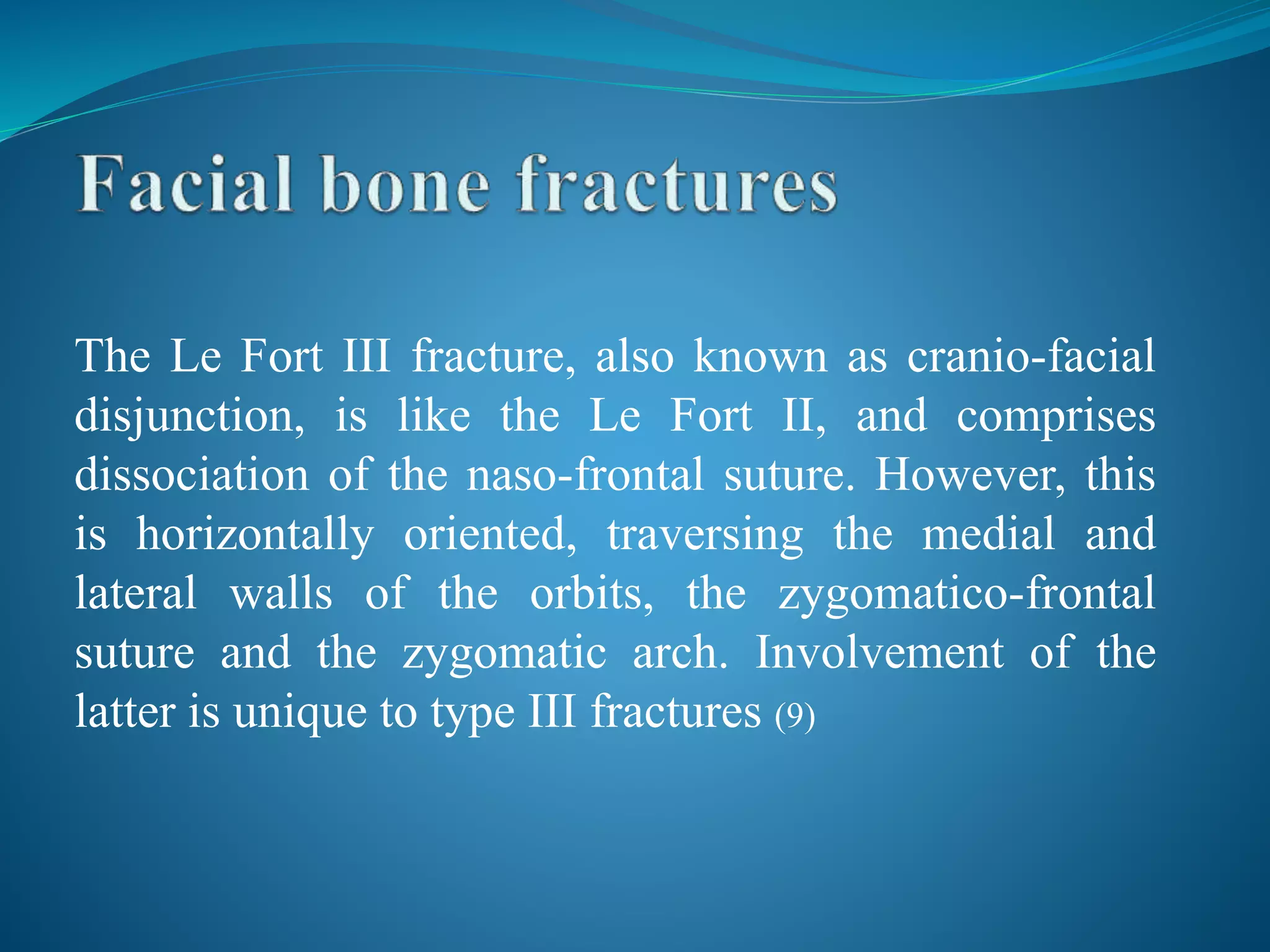

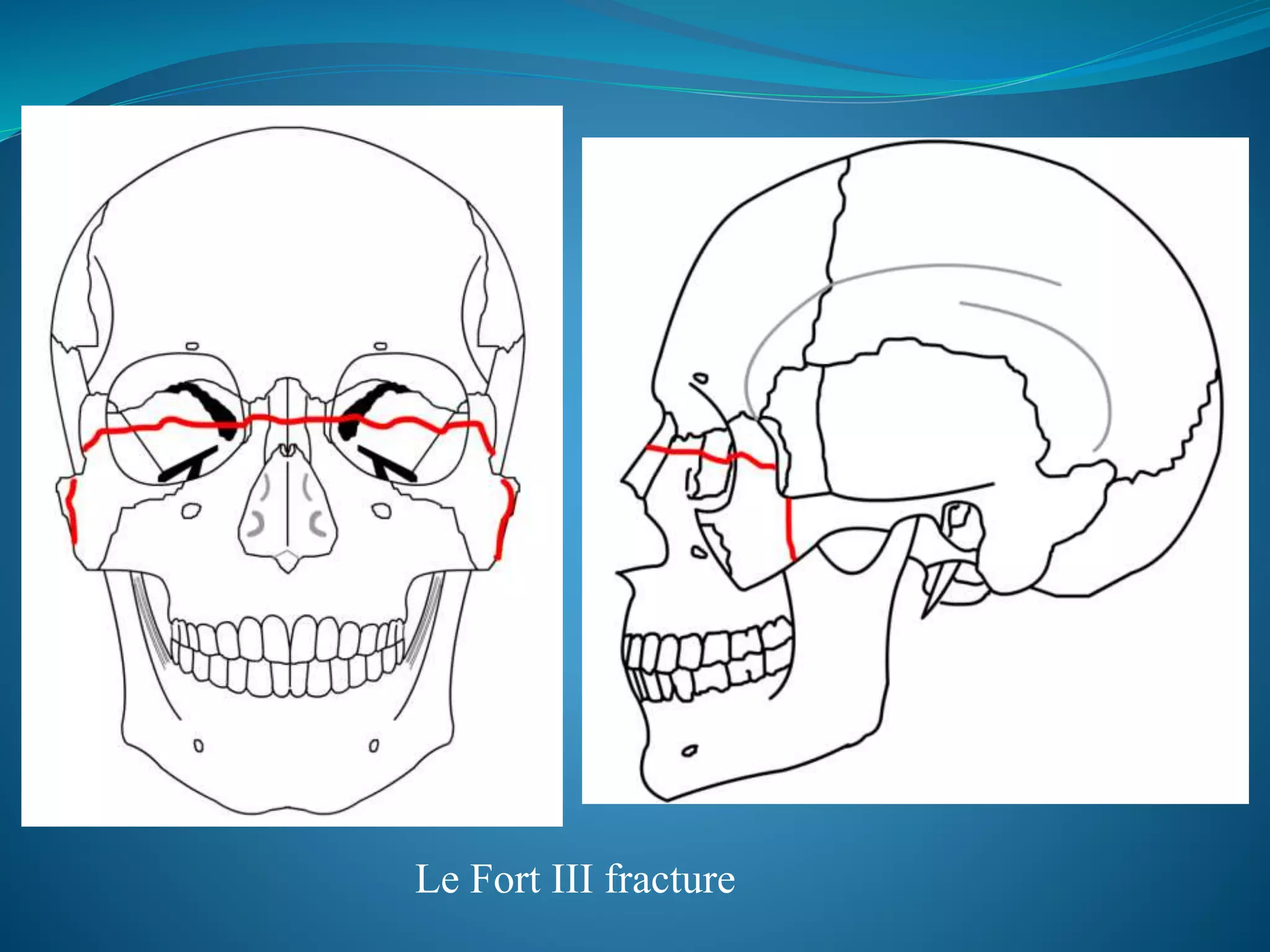

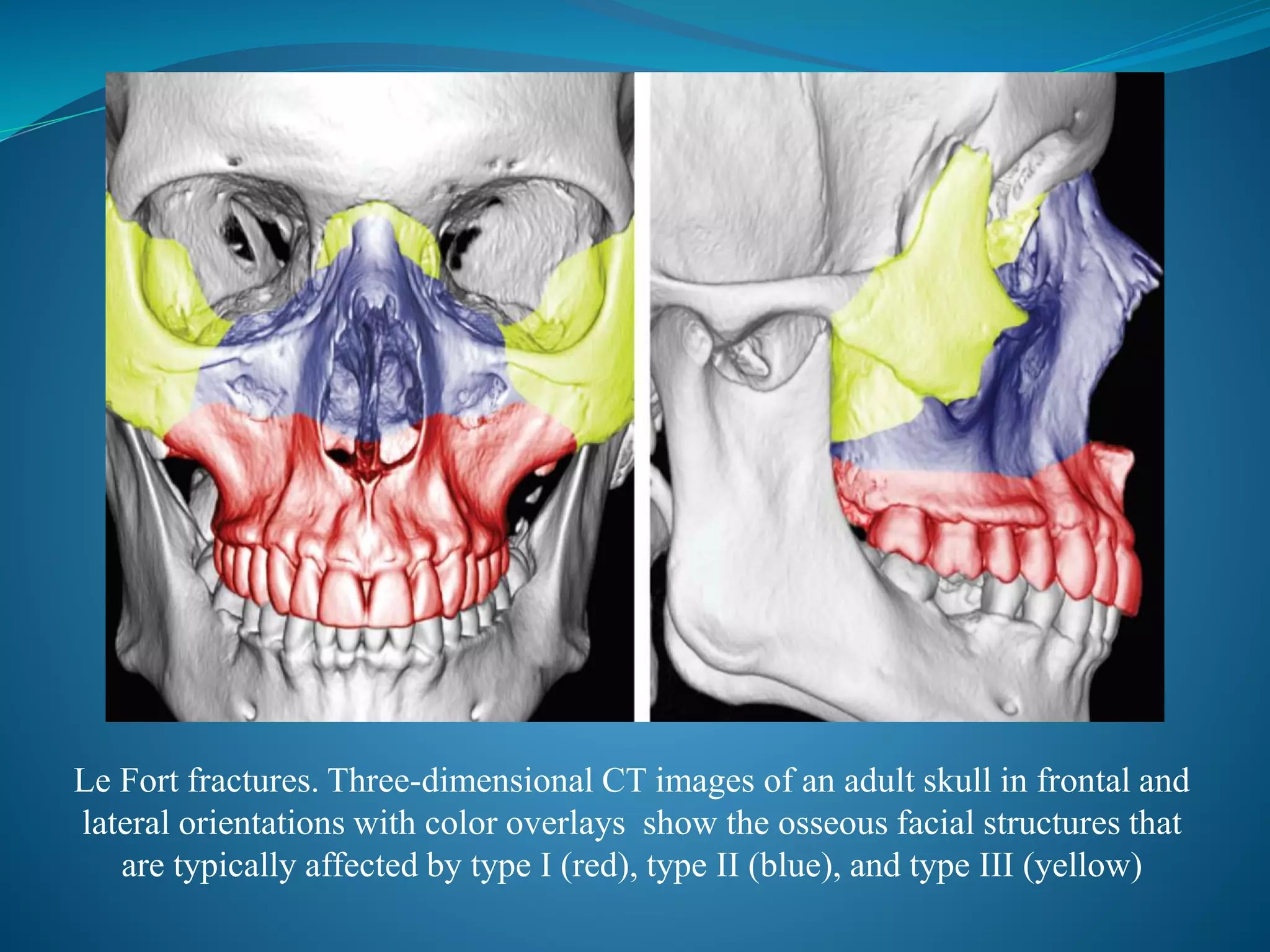

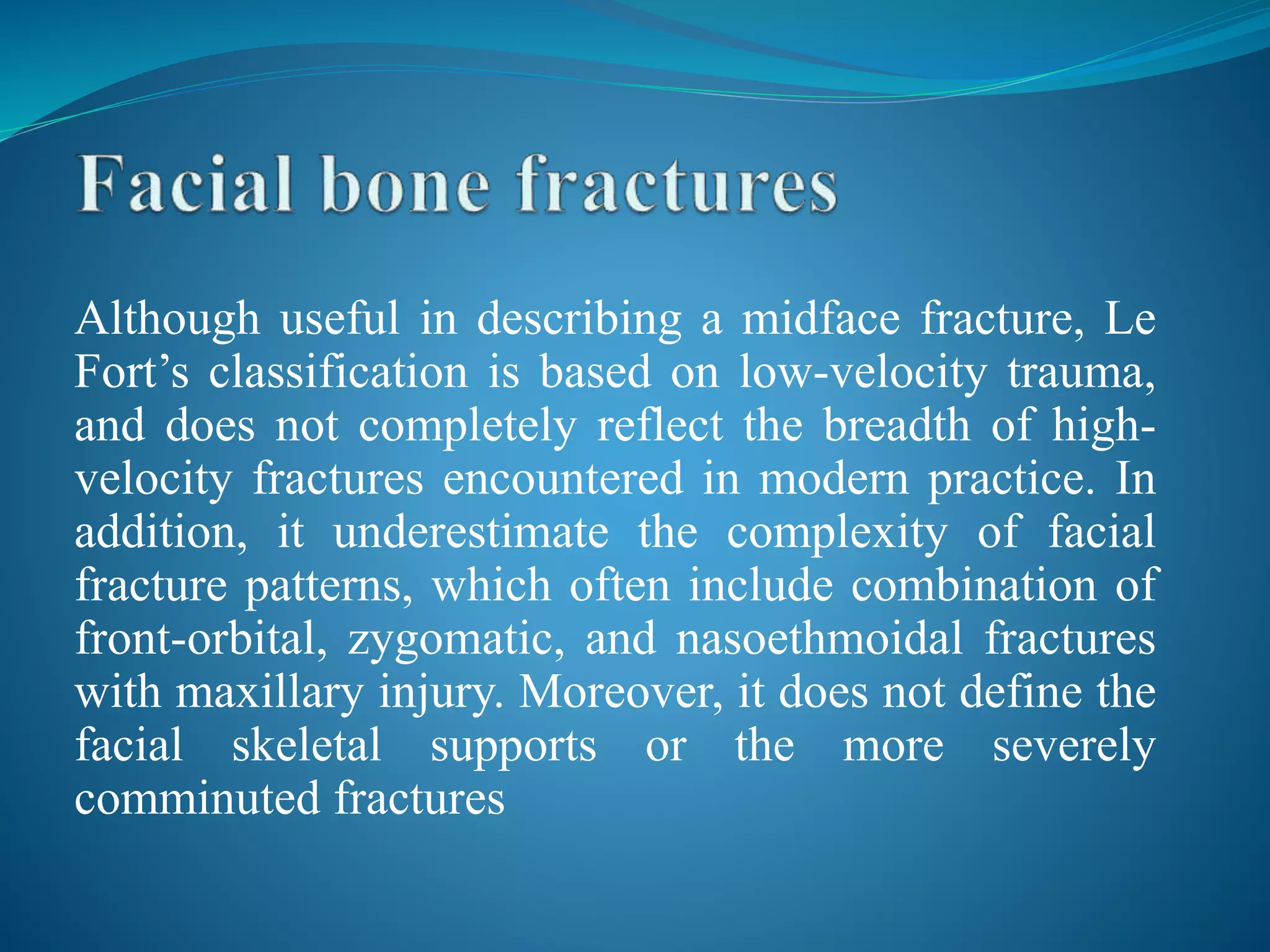

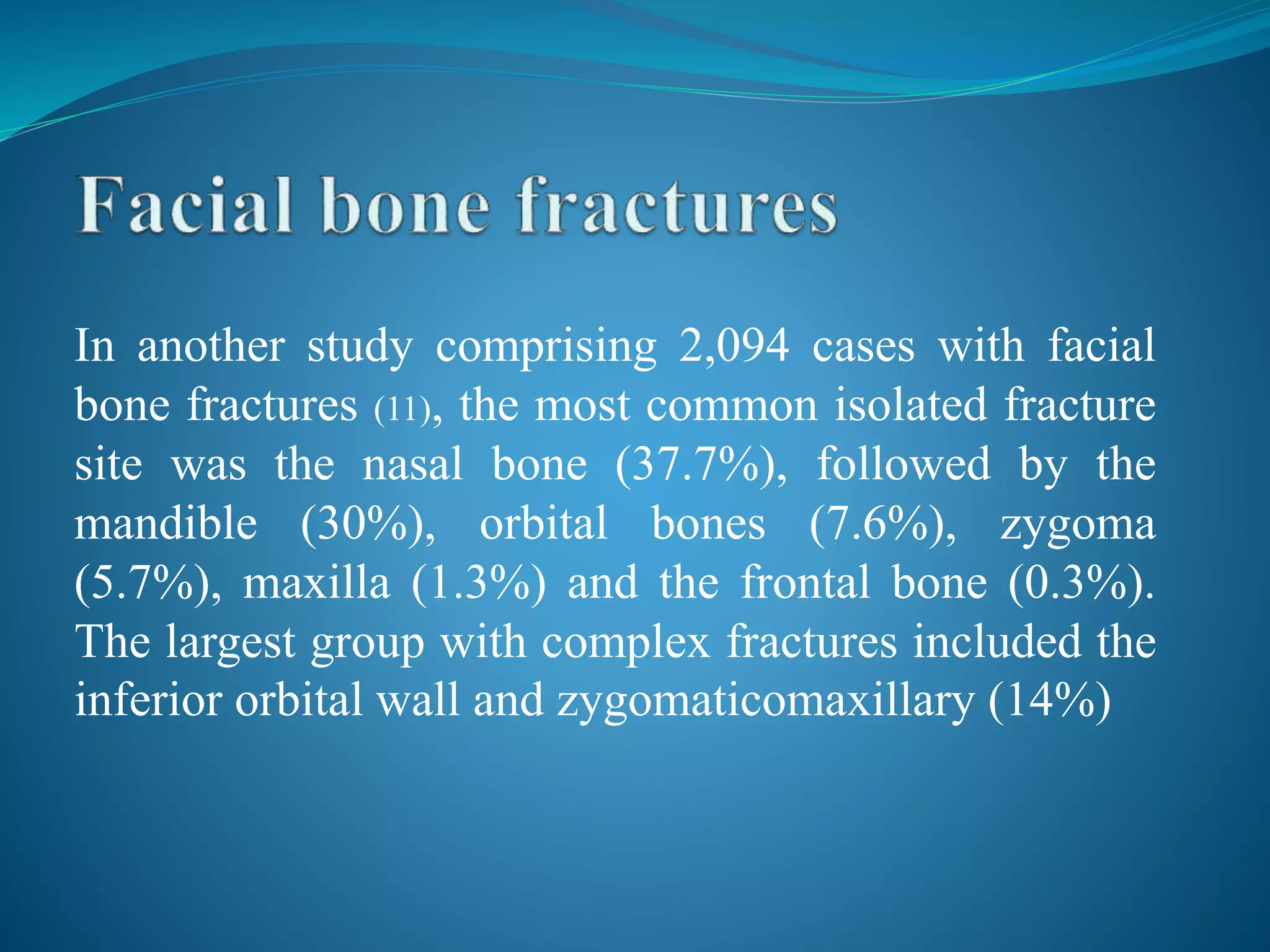

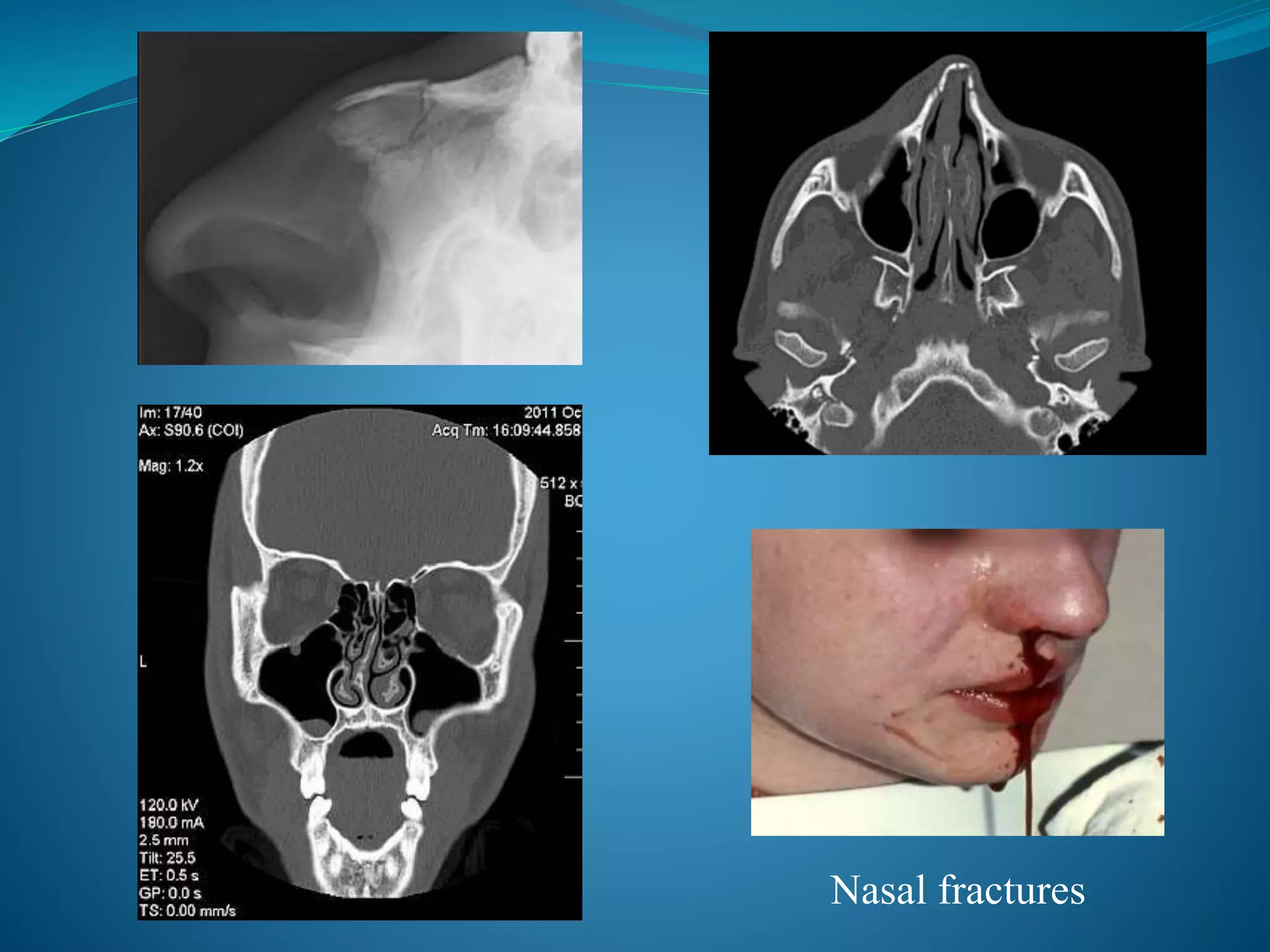

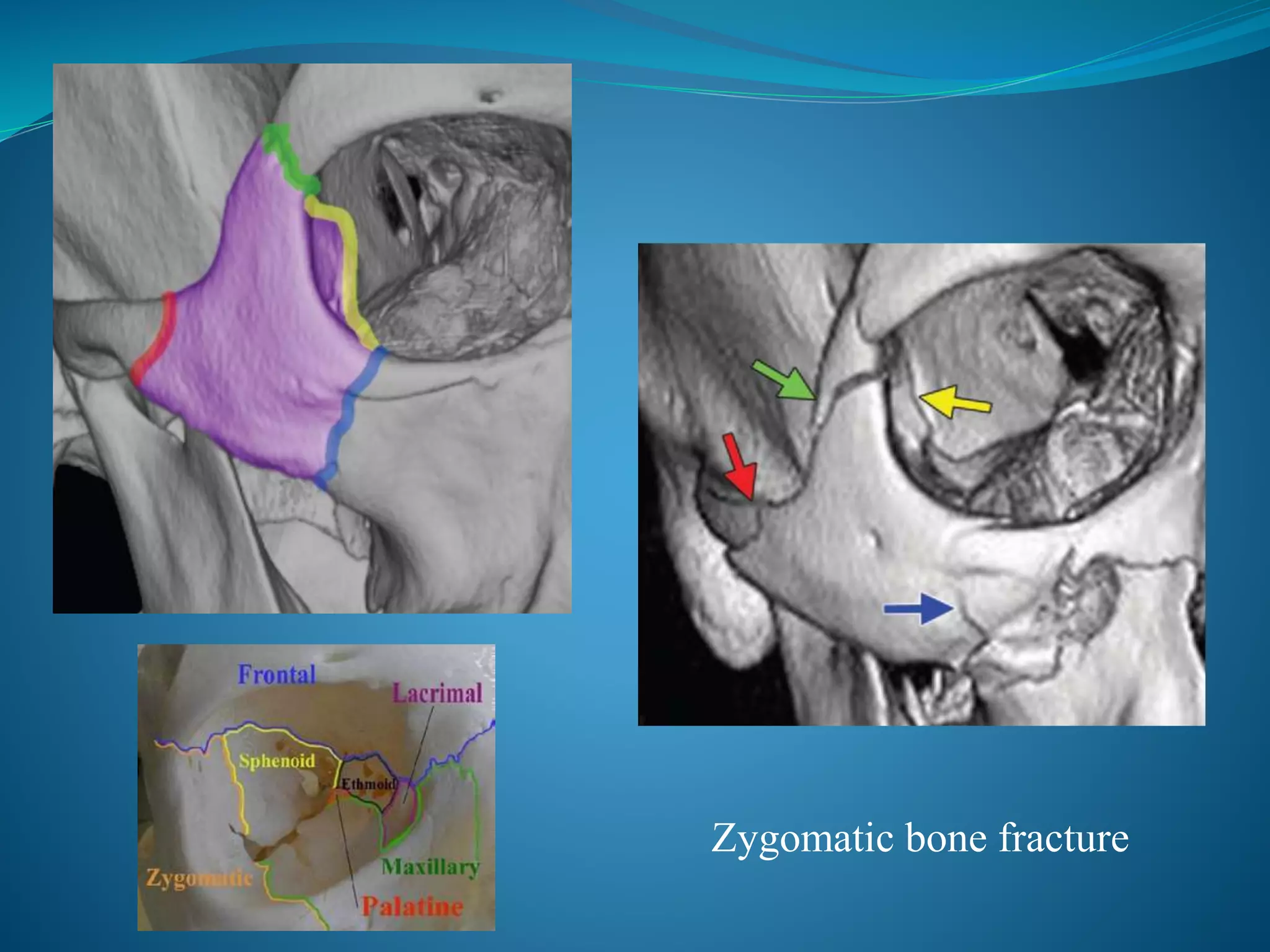

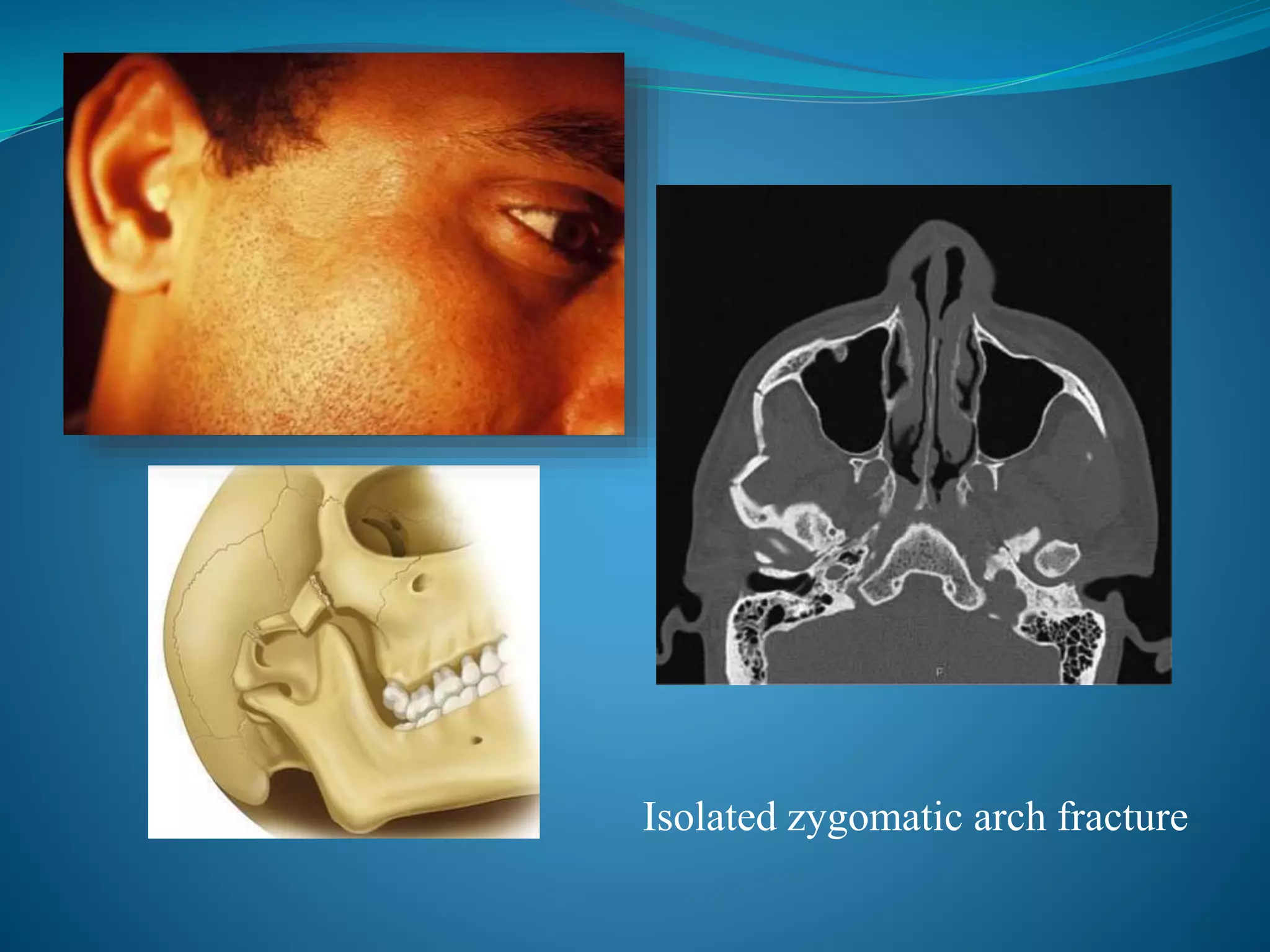

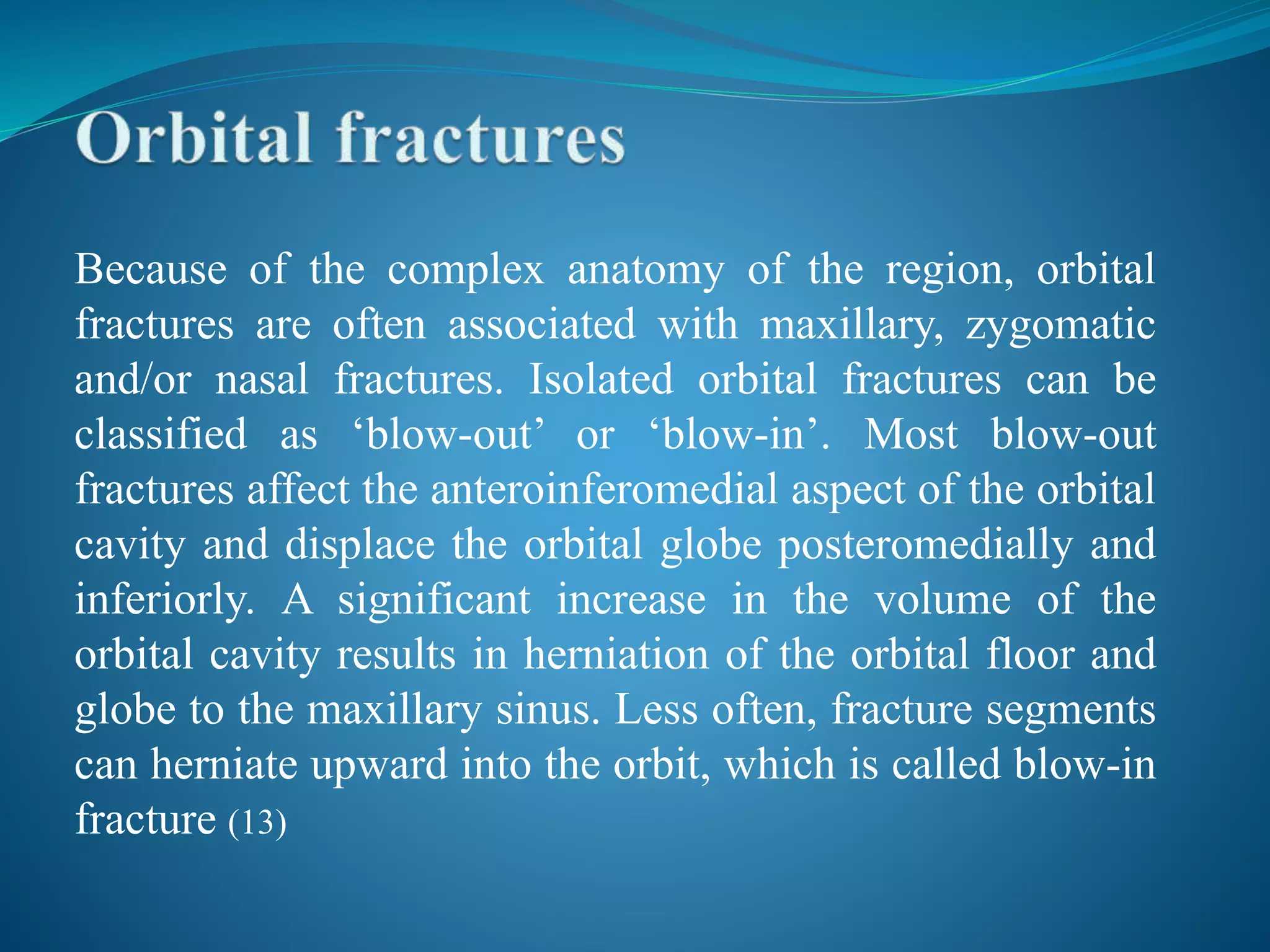

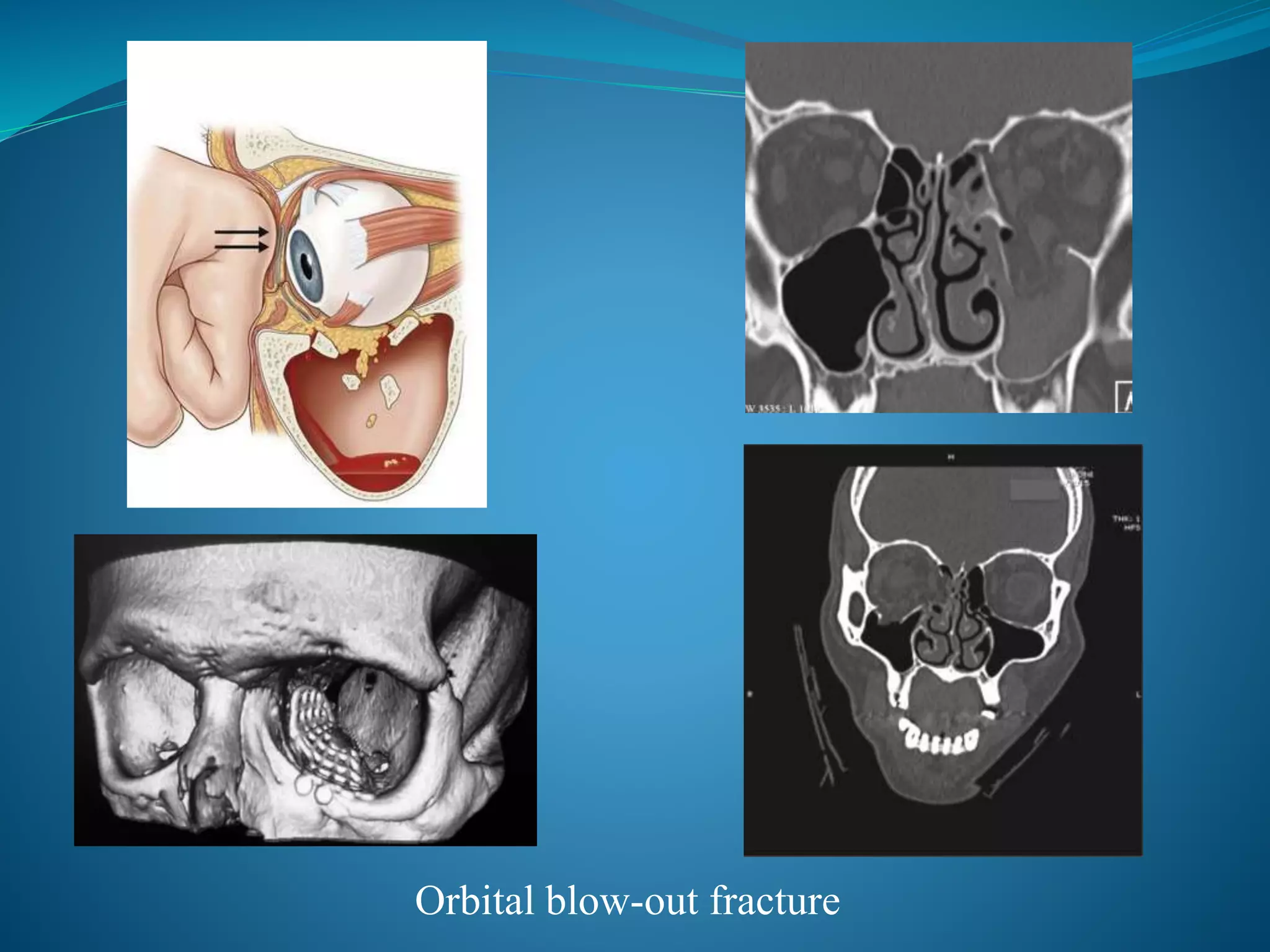

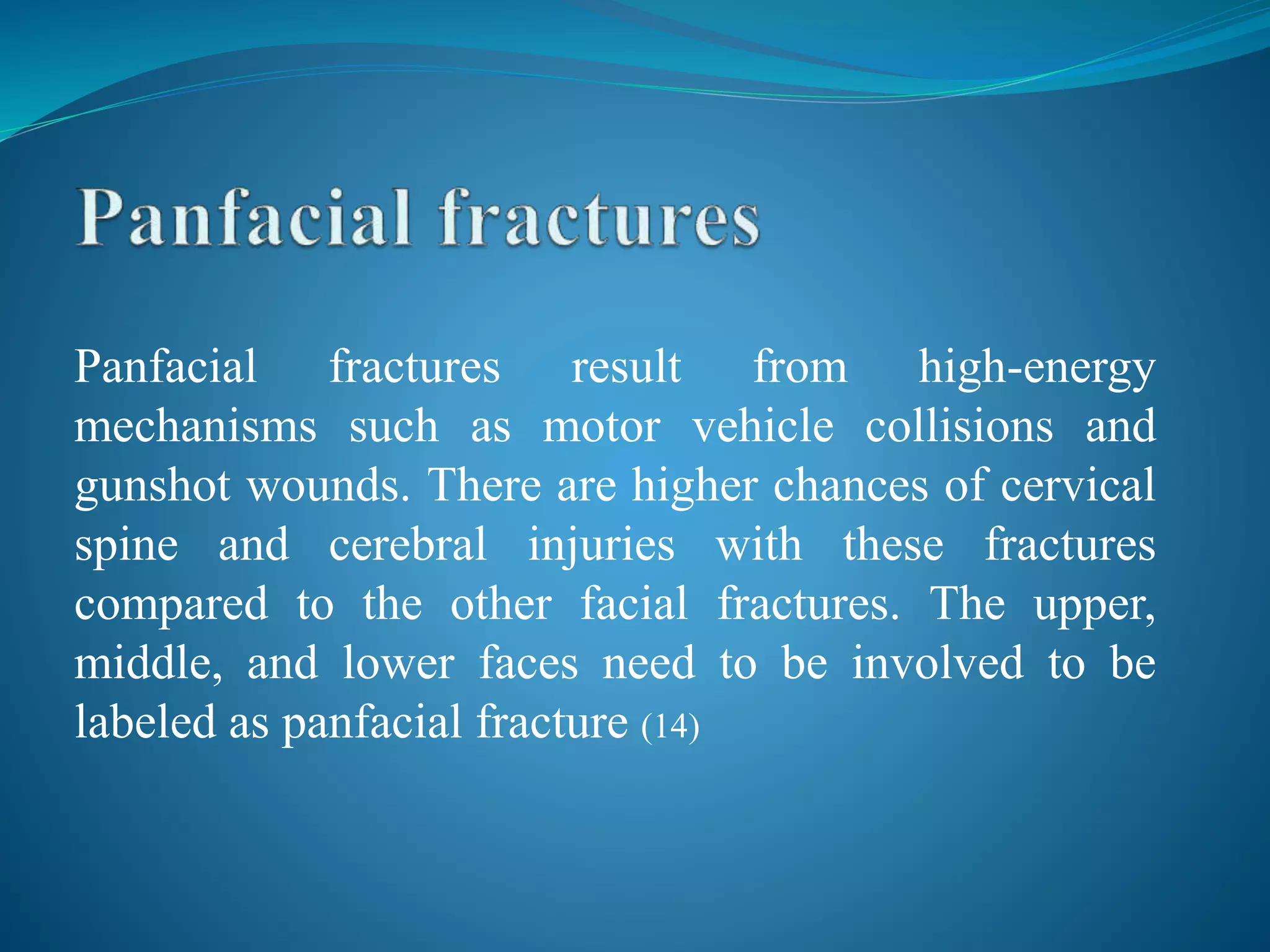

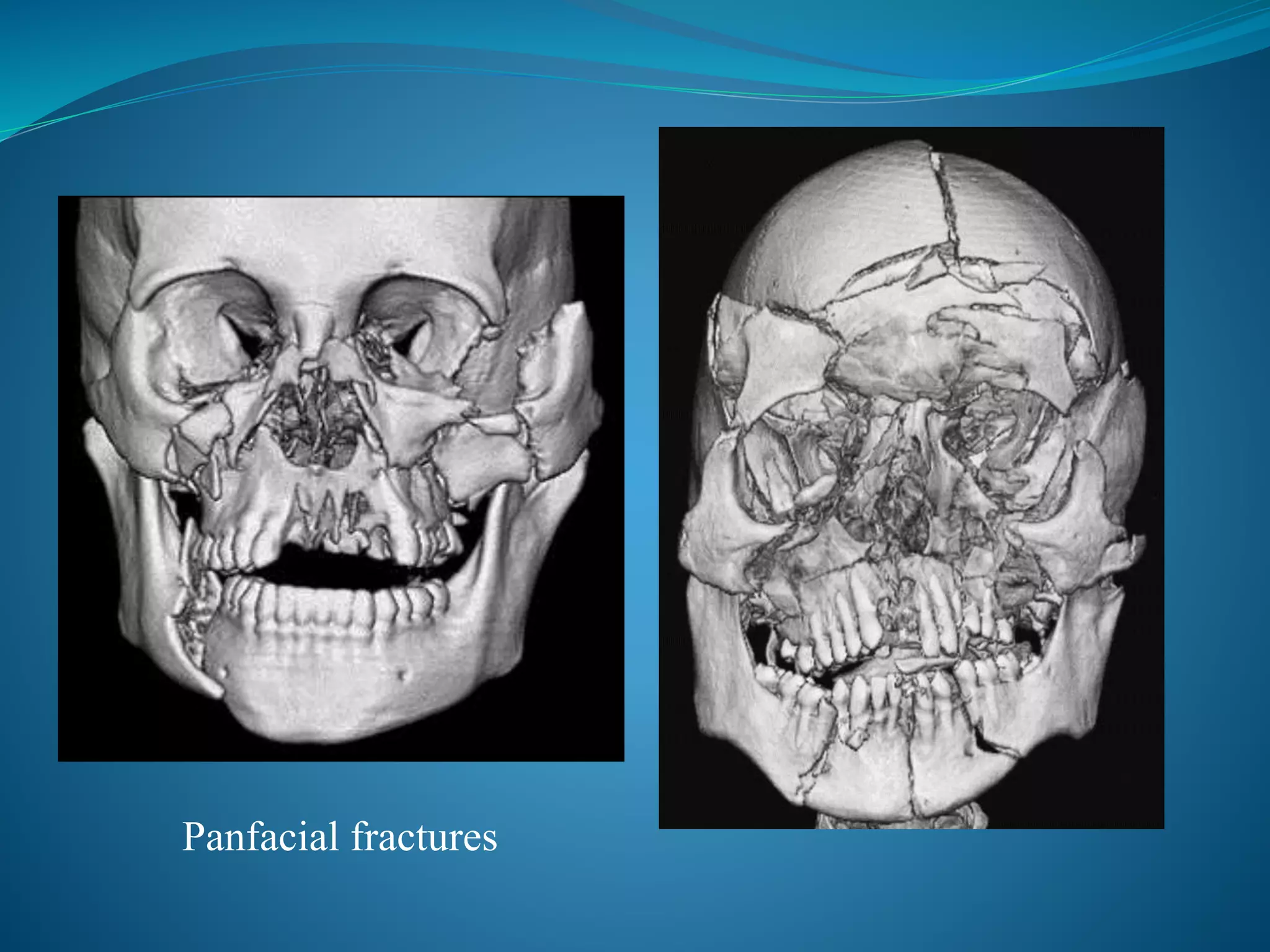

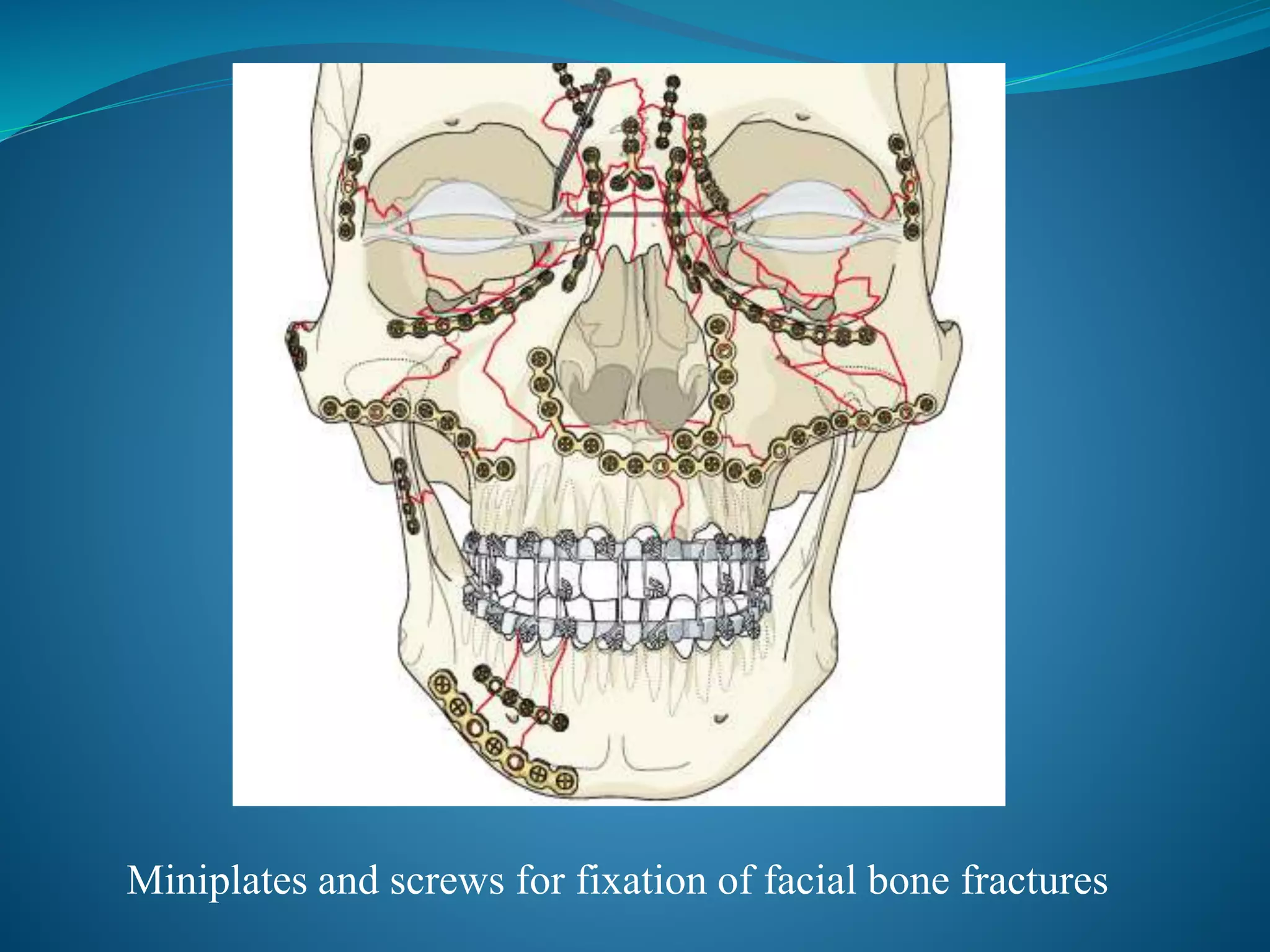

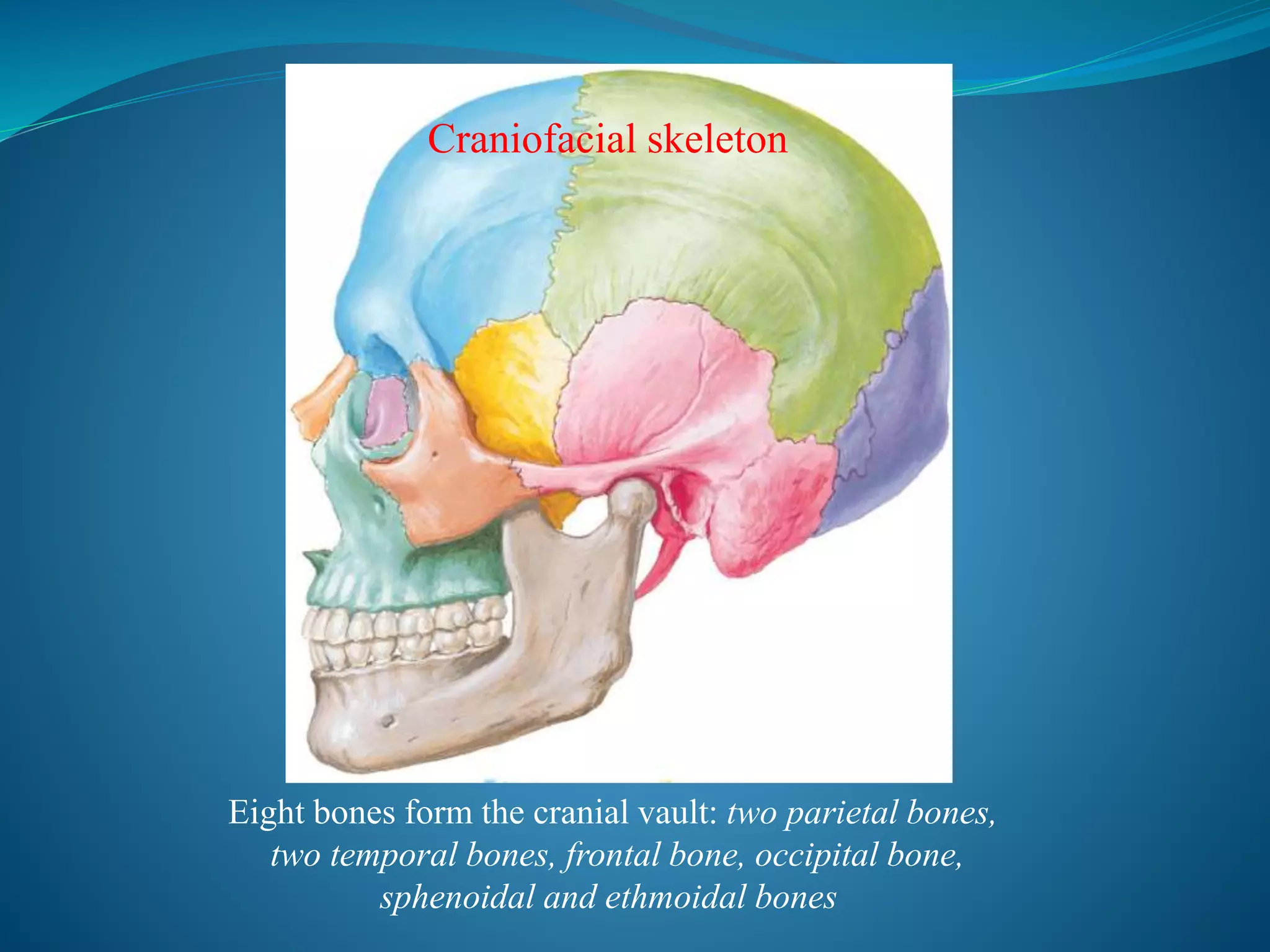

The document discusses the anatomy and biomechanics of facial bone fractures. It begins by describing the structures that make up the skull - the cranial vault, base, and facial skeleton. It then discusses the classification of common midface fractures according to the Le Fort system. The rest of the document details the epidemiology, characteristics, and treatment of various types of facial fractures including nasal, orbital, zygomatic, panfacial and mandibular fractures. Modern treatment primarily involves early open reduction and internal fixation using miniplates and screws.

![Fifteen irregular bones form the facial skeleton:

three singular bones lying in the midline;

mandible, ethmoid, and vomer and six paired

bones occurring bilaterally; maxilla,

inferior nasal concha [turbinate], zygomatic,

palatine, nasal, and lacrimal bones

Facial skeleton](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/facialbonefracturesanoverview-181009143904/75/Facial-bone-fractures-an-overview-6-2048.jpg)