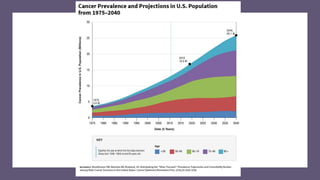

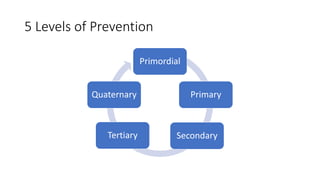

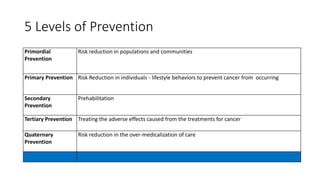

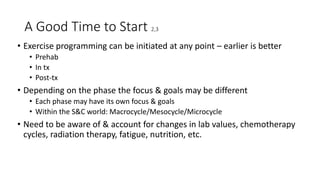

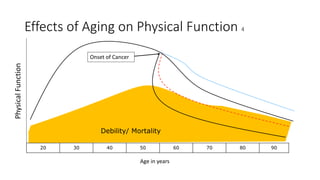

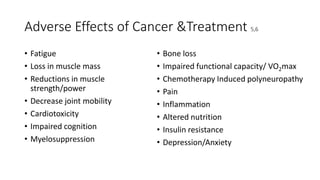

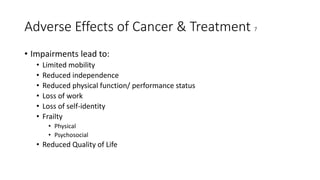

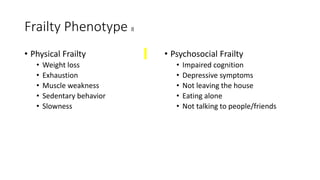

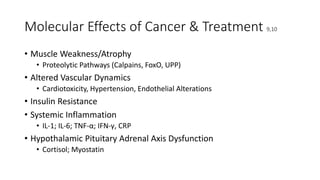

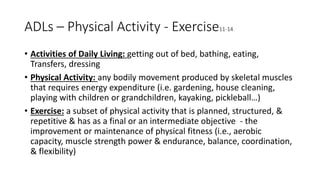

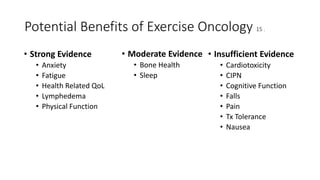

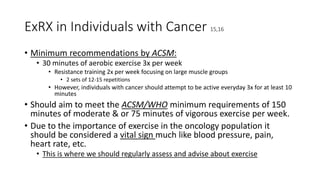

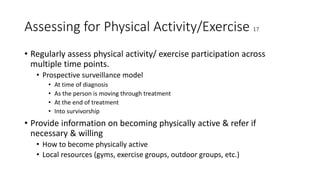

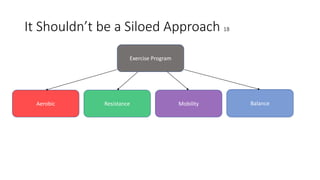

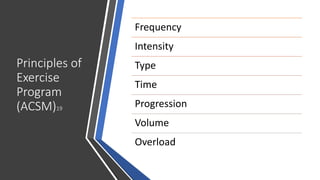

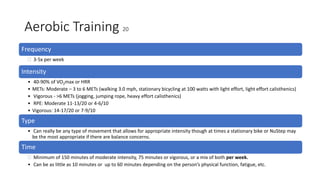

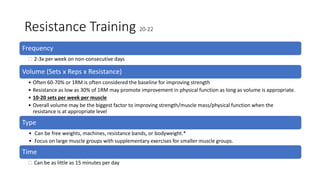

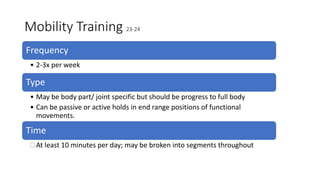

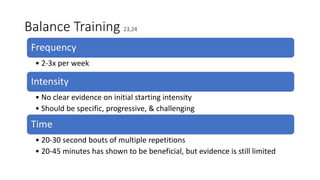

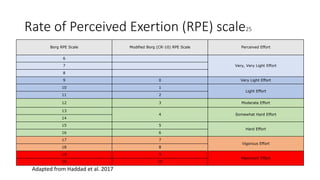

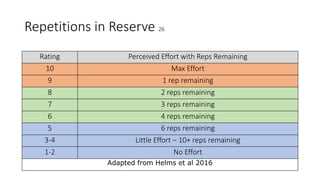

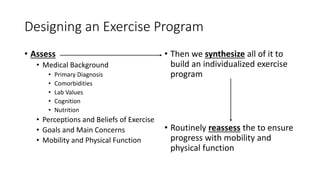

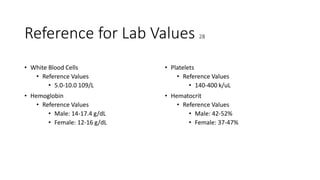

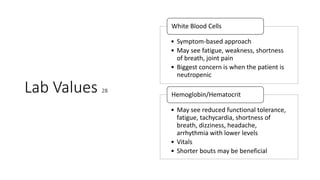

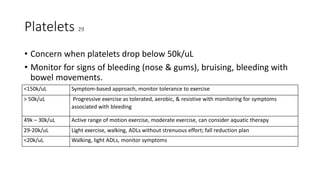

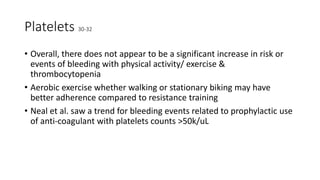

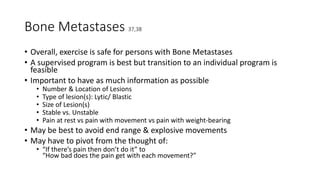

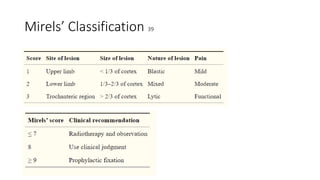

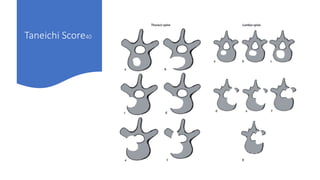

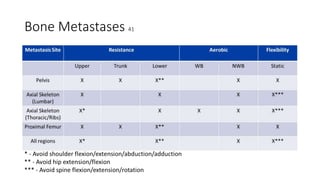

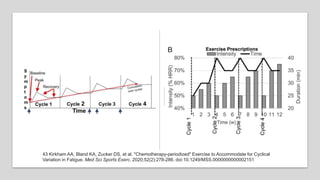

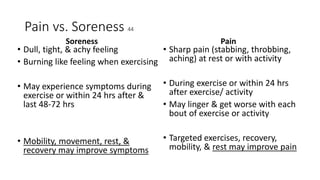

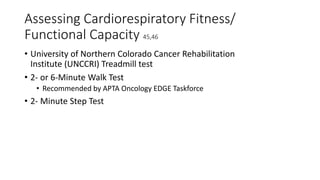

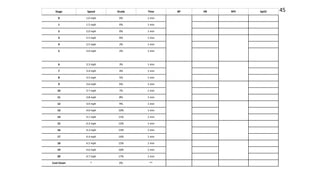

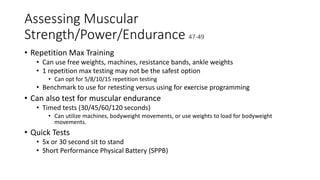

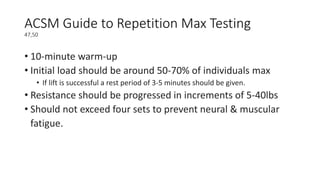

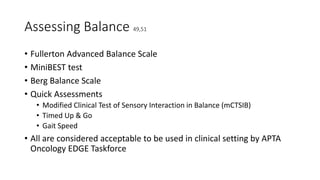

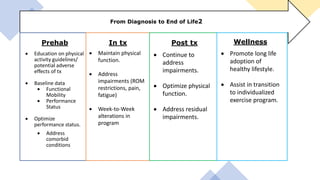

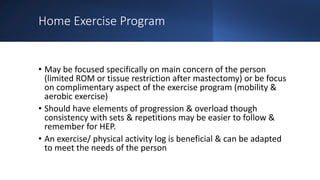

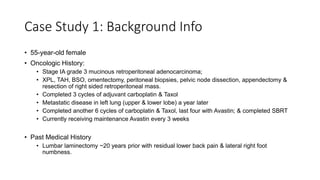

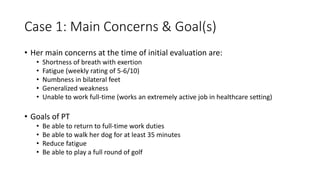

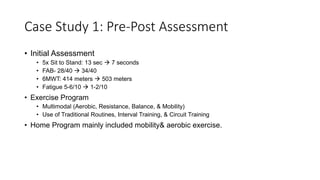

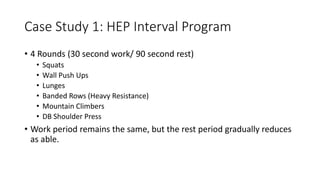

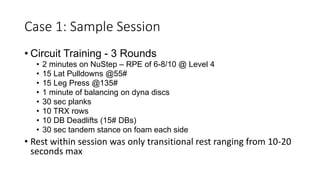

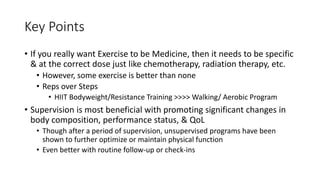

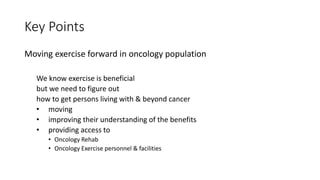

The document outlines exercise oncology principles, highlighting the importance of physical activity and exercise for individuals with cancer at various stages of treatment. It discusses the five levels of cancer prevention, benefits of exercise, and offers guidelines for individualized exercise programs while addressing potential challenges faced by cancer patients. Emphasis is placed on assessing physical function and adapting exercise recommendations based on lab values and treatment status.