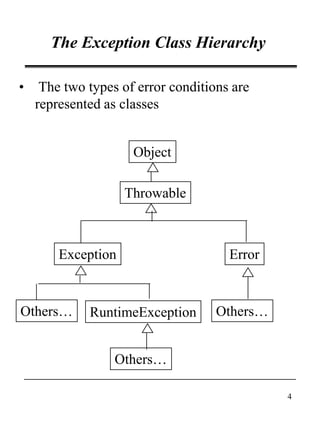

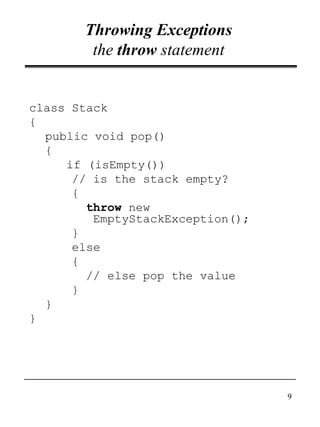

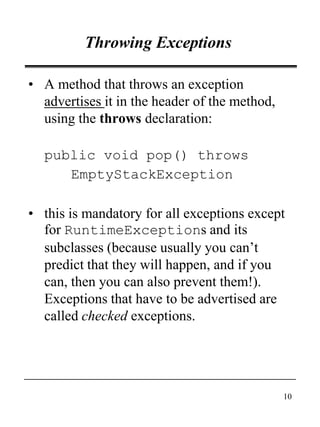

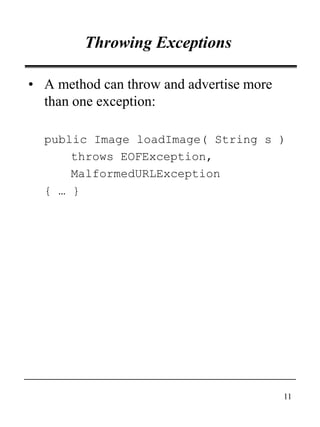

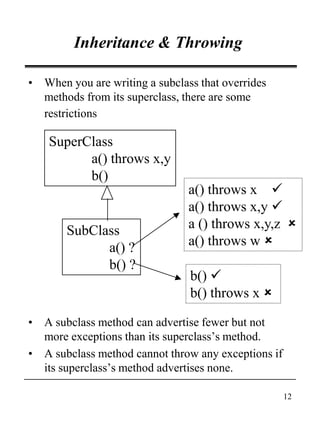

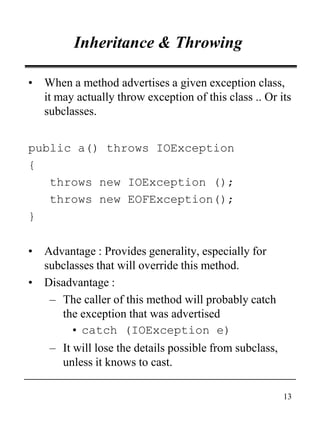

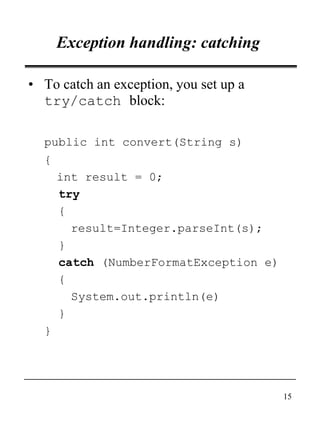

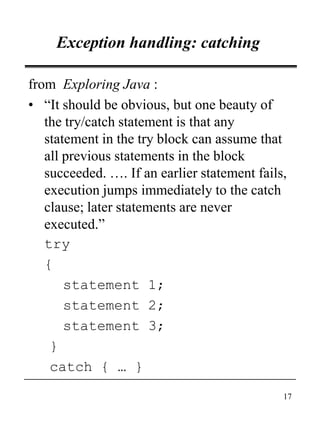

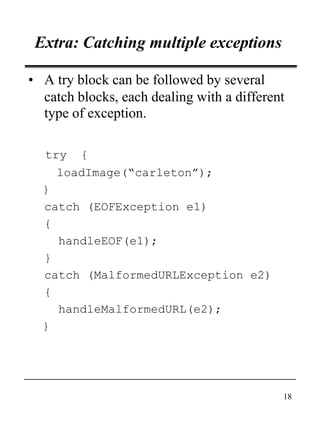

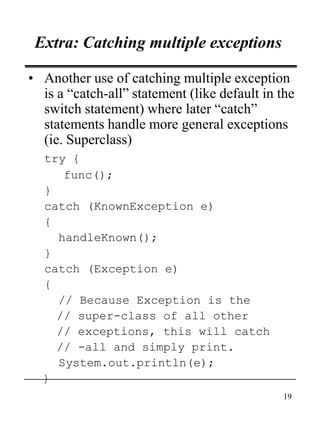

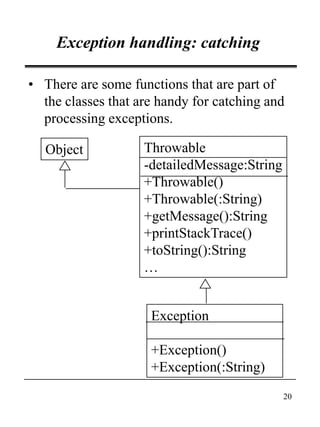

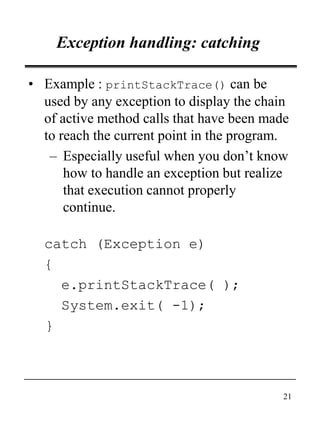

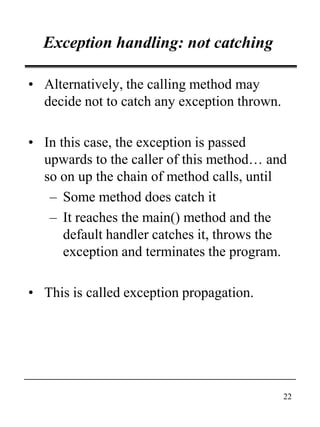

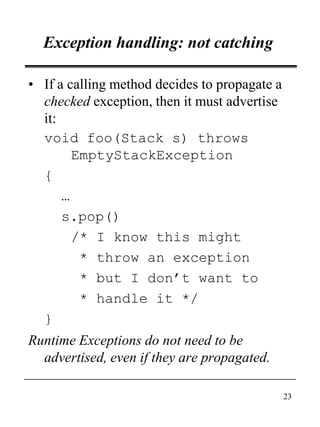

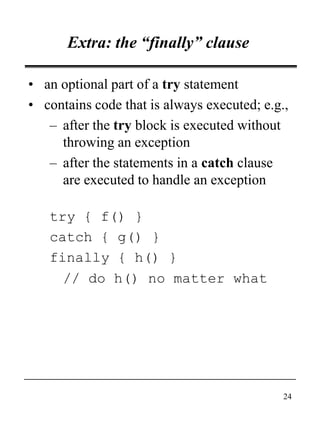

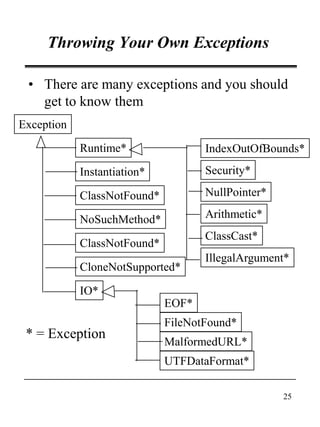

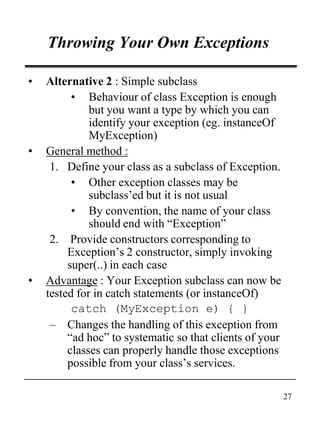

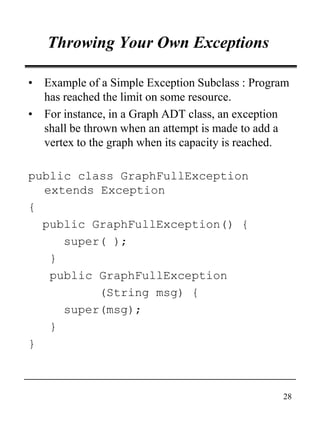

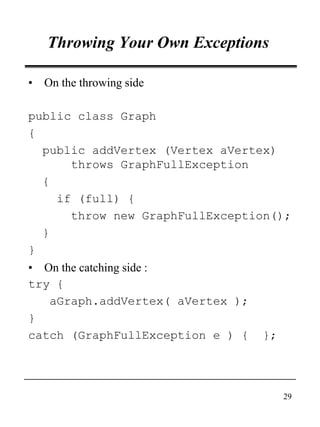

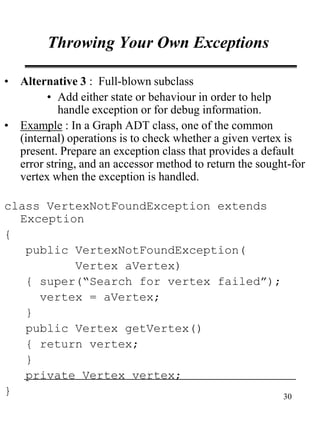

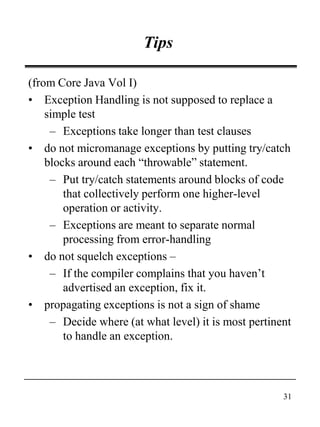

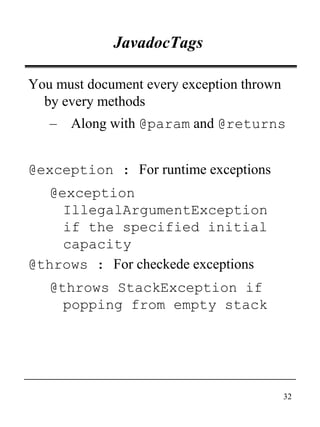

This document discusses Java's exception handling mechanisms. It describes the exception class hierarchy, with Exception and Error as top-level classes. Exceptions represent errors in an application, while Errors represent internal Java errors. Exceptions can be thrown using throw statements and caught using try-catch blocks. Custom exceptions can be created by subclassing Exception. Exceptions provide object-oriented features like state and behavior. Finally, tips are provided around proper exception handling practices in Java.