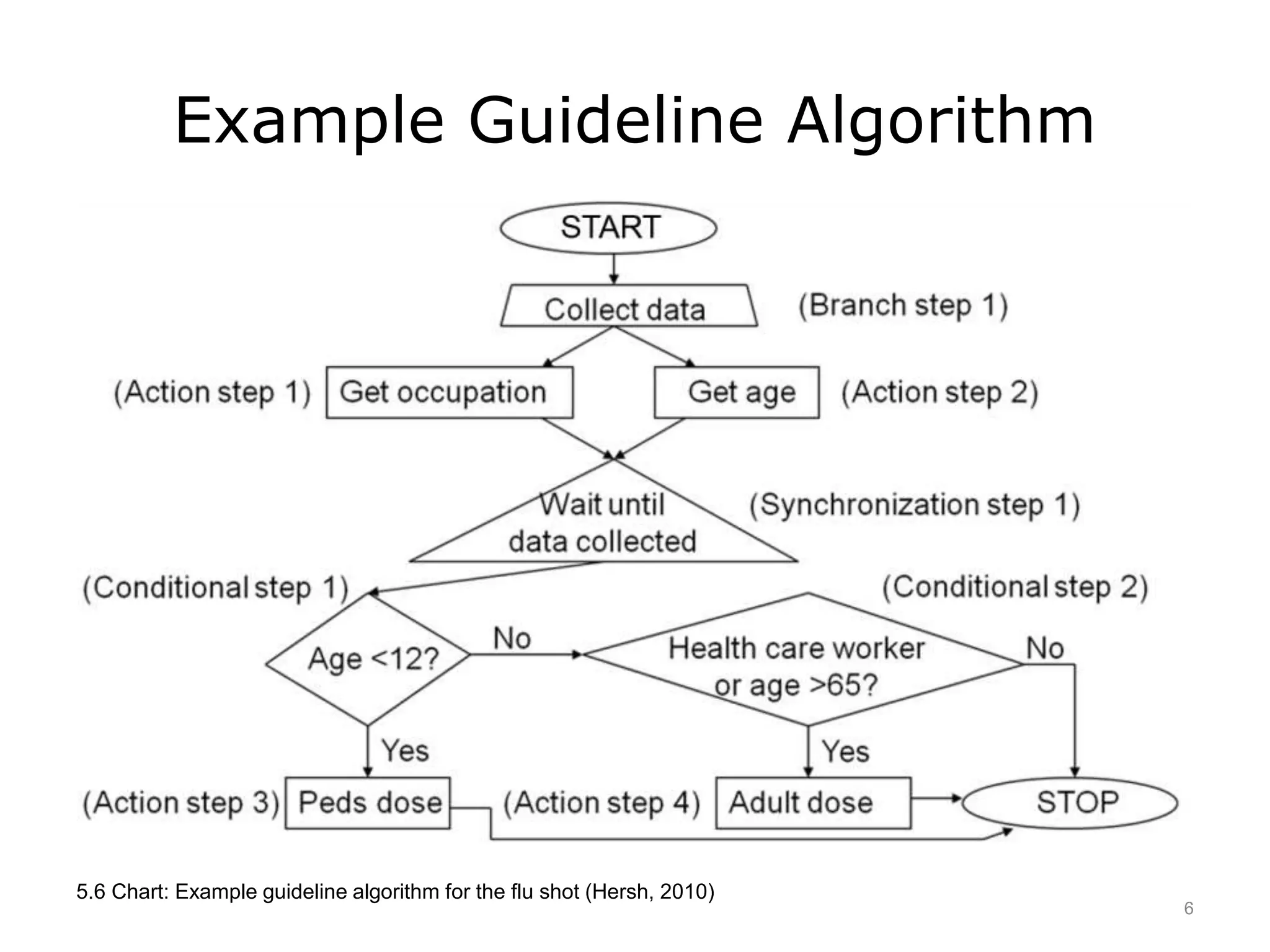

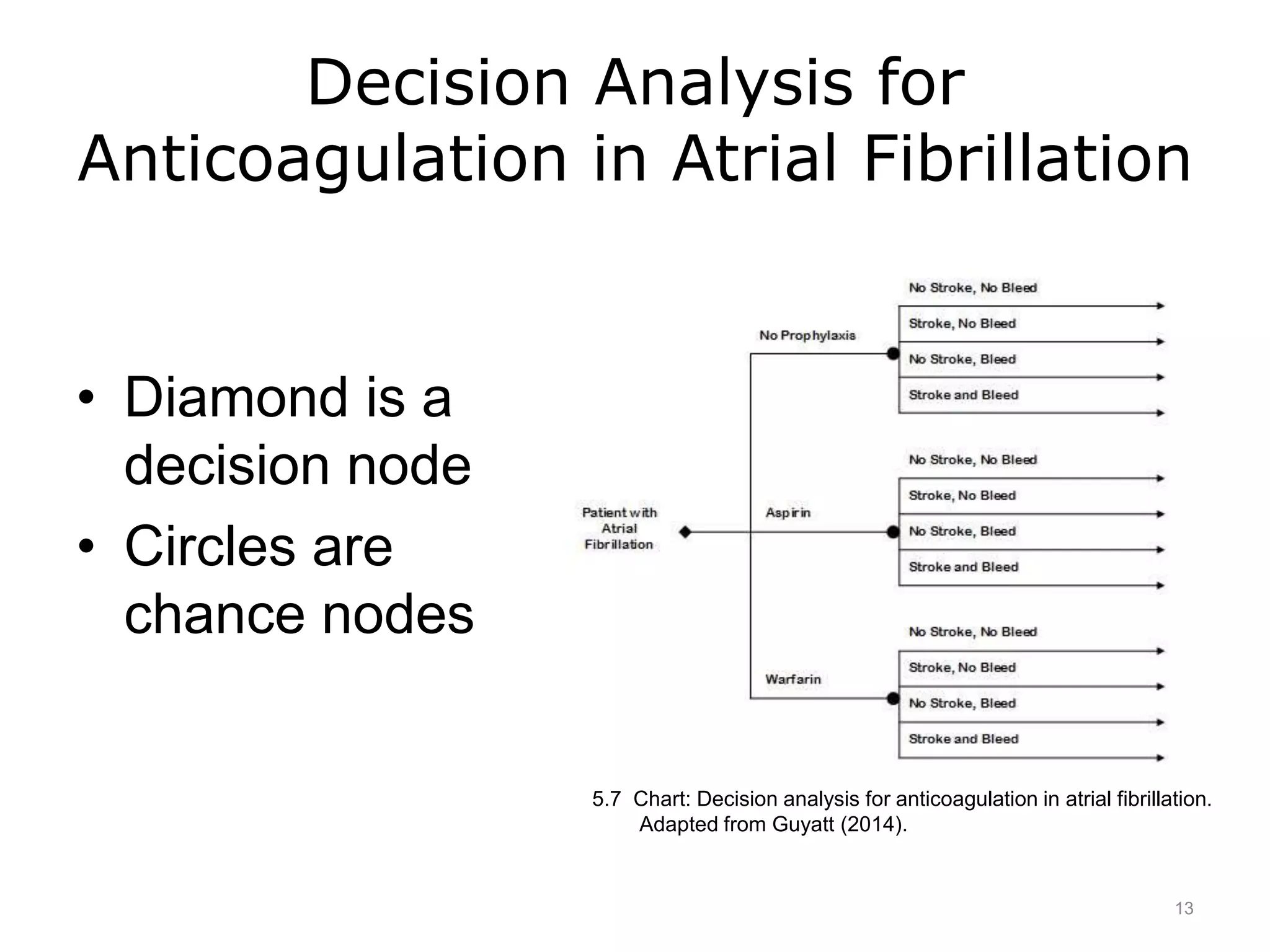

This document discusses how evidence-based practice is used in clinical settings through clinical practice guidelines and decision analysis. It defines clinical practice guidelines as a series of steps for providing clinical care and decision analysis as a formal structure for integrating evidence about treatment options. Clinical practice guidelines aim to standardize and improve care but have limitations such as not applying to complex patients. Decision analysis allows for elucidating optimal individual decisions but requires significant time and resources. Overall, evidence-based practice provides tools and approaches to inform clinical decision-making.