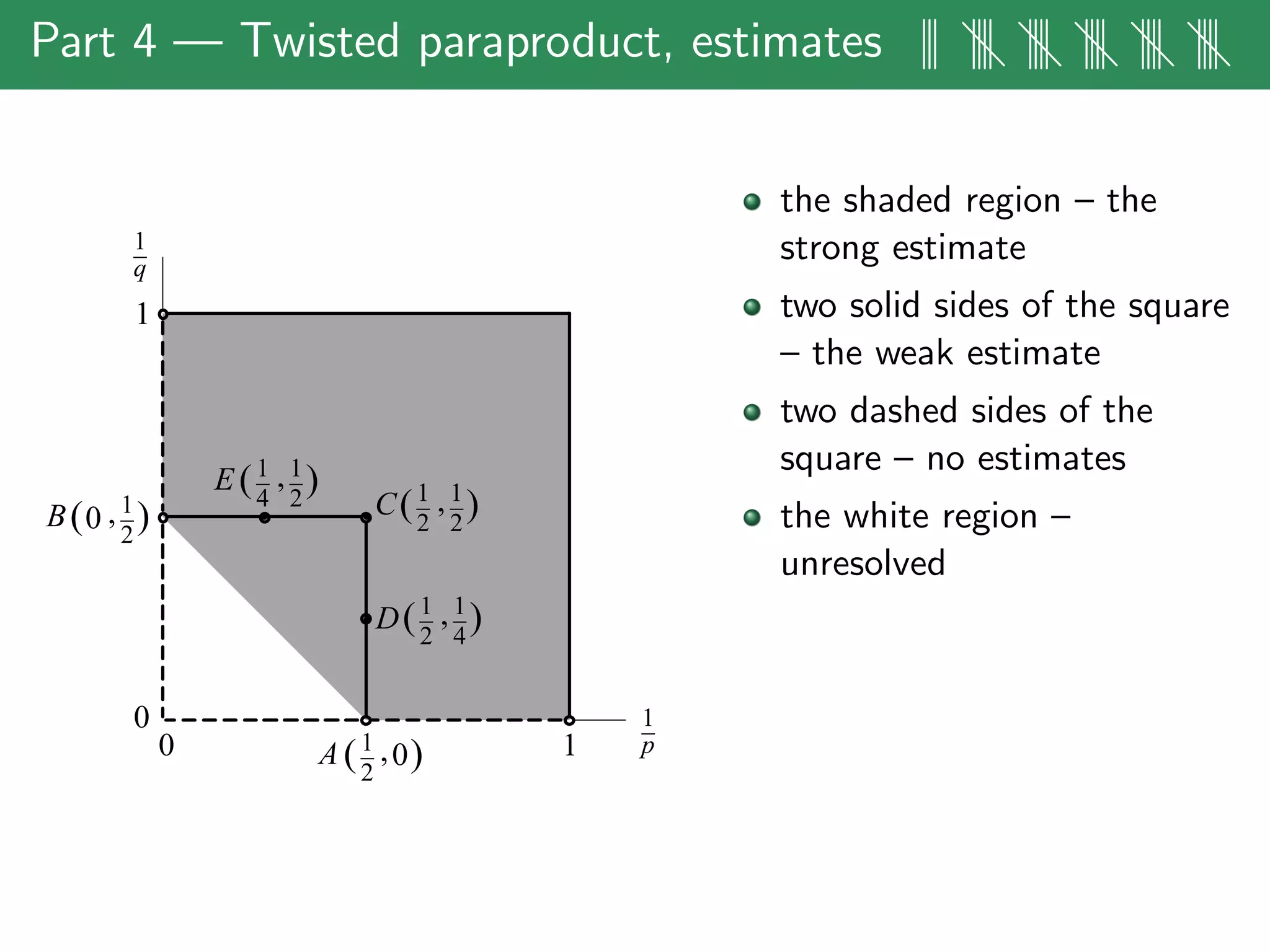

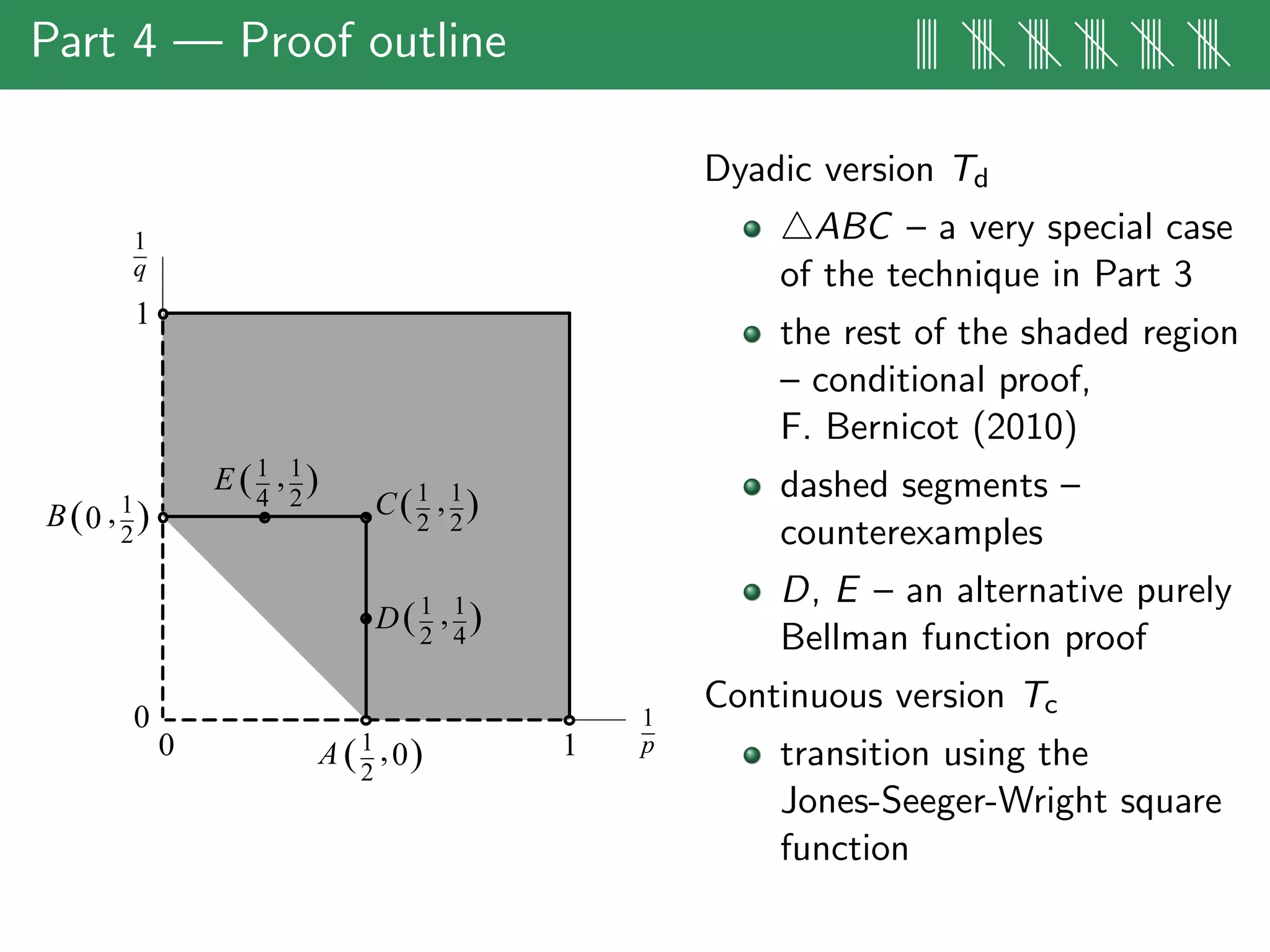

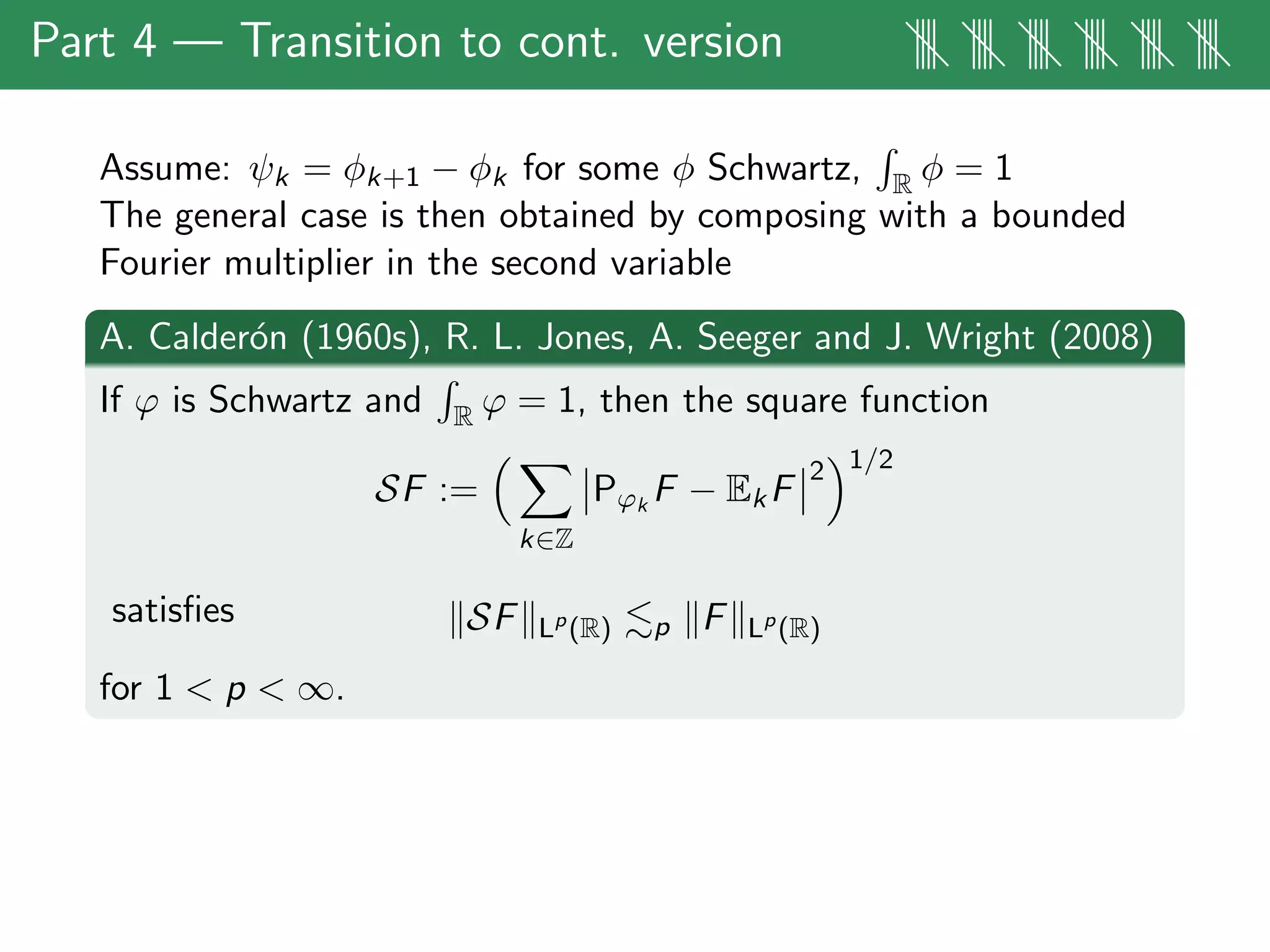

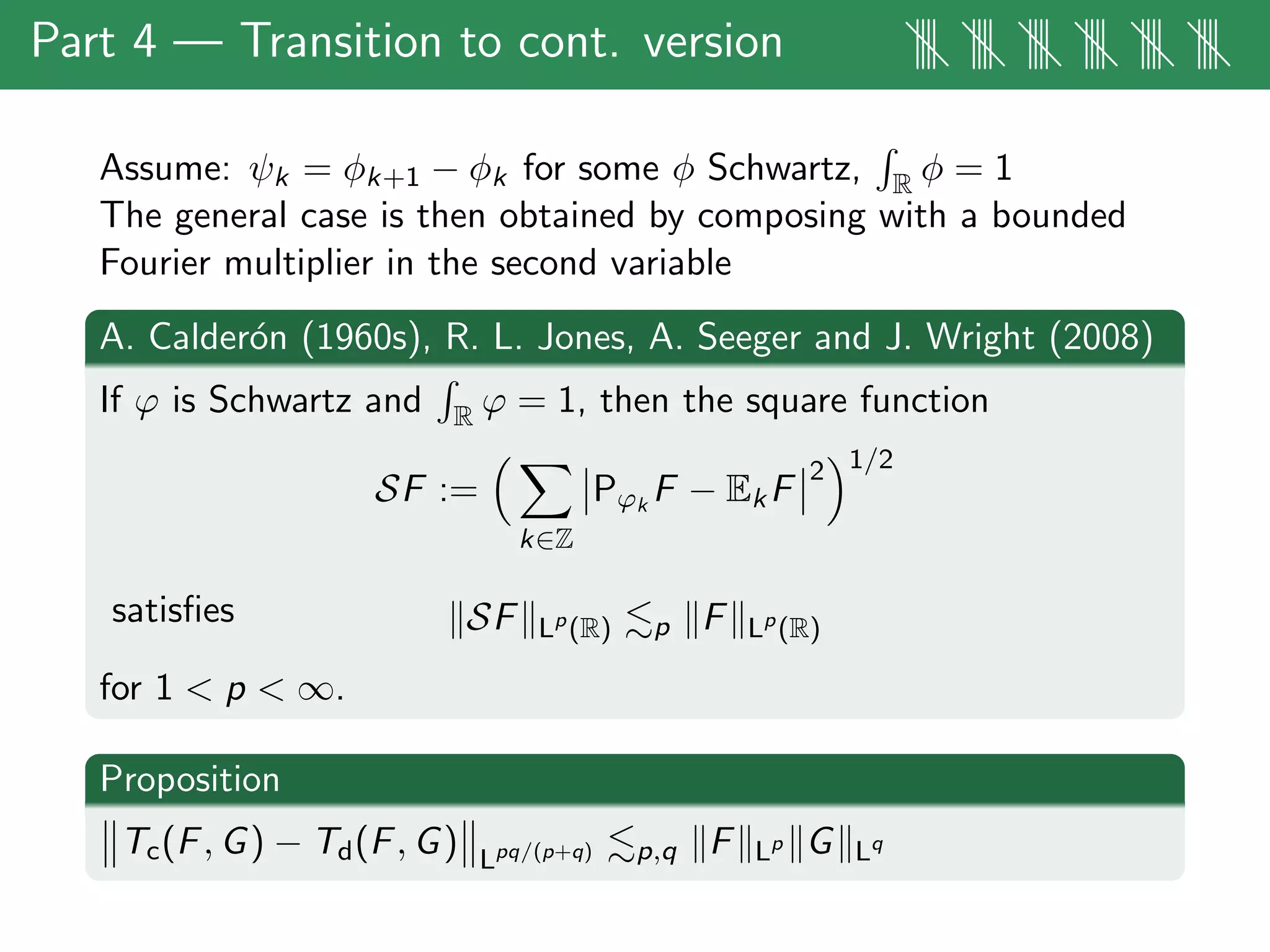

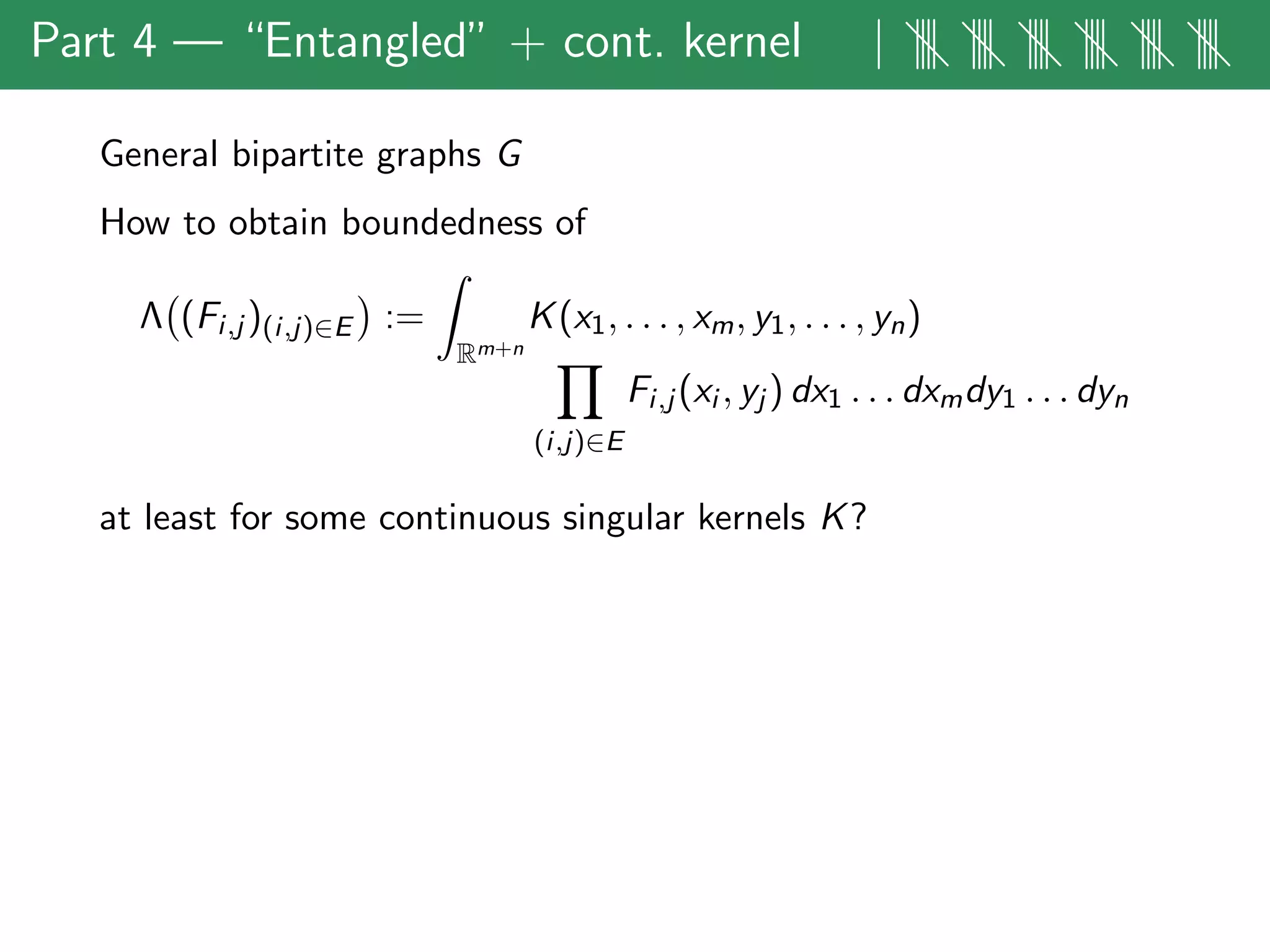

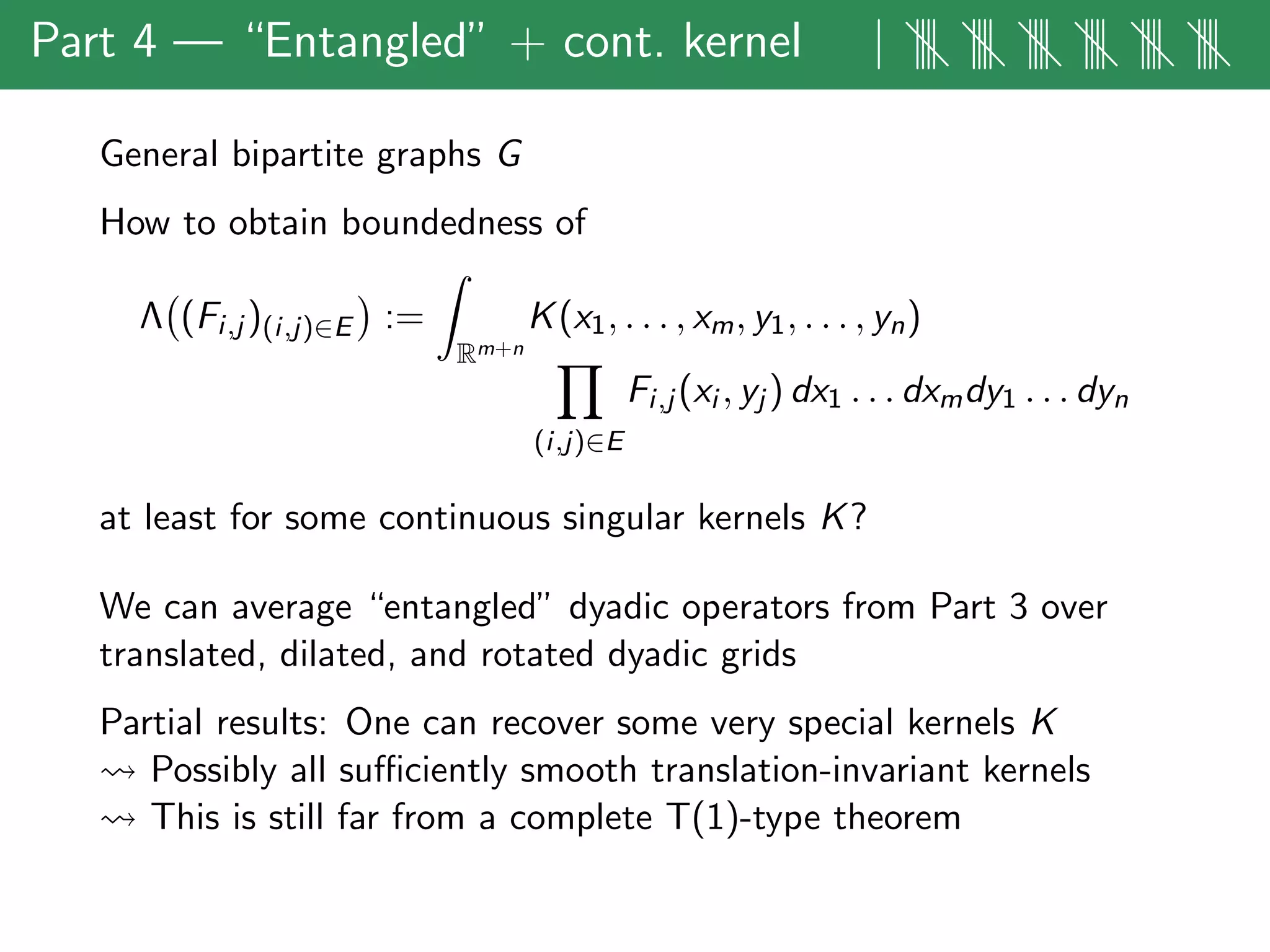

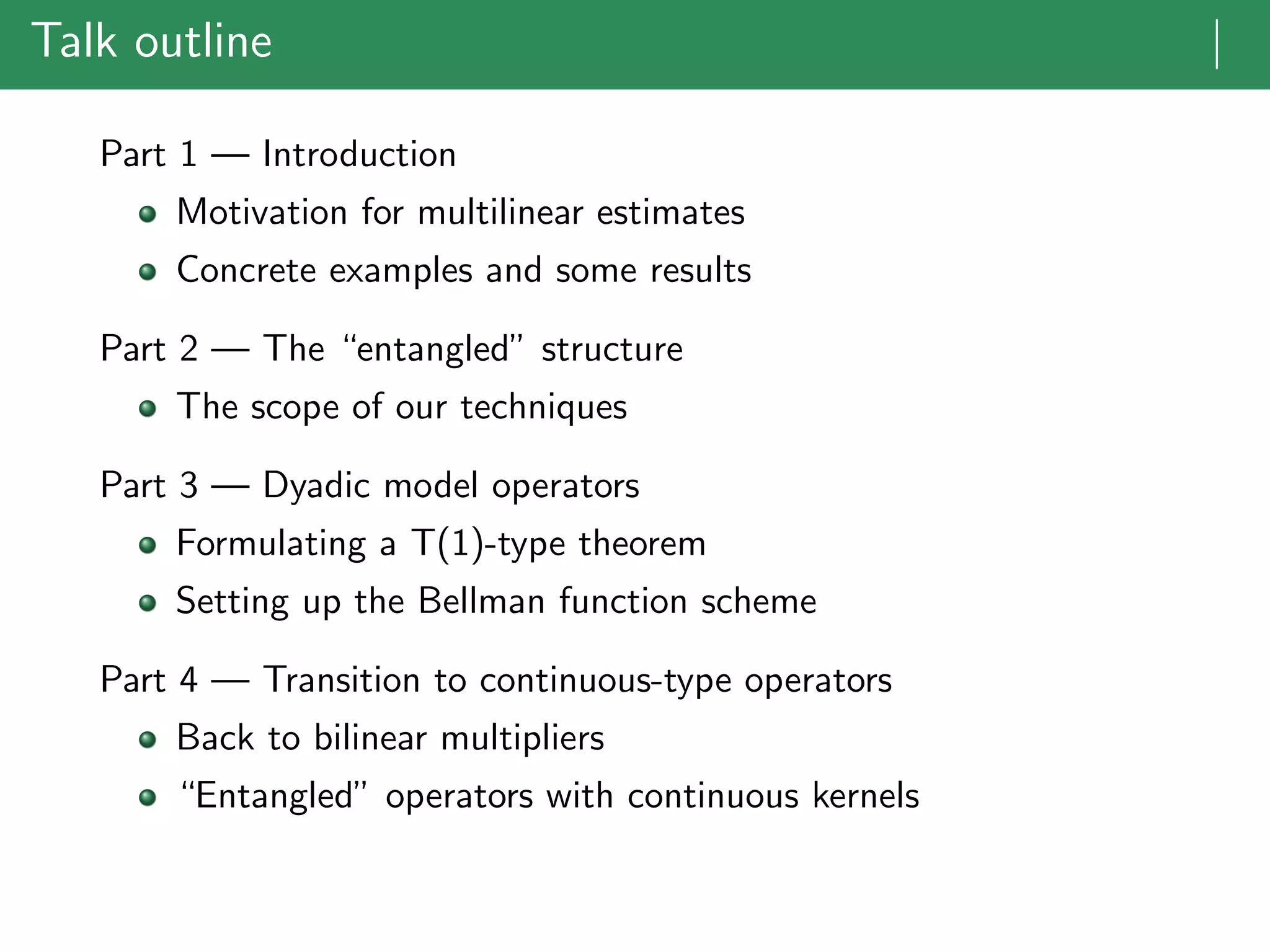

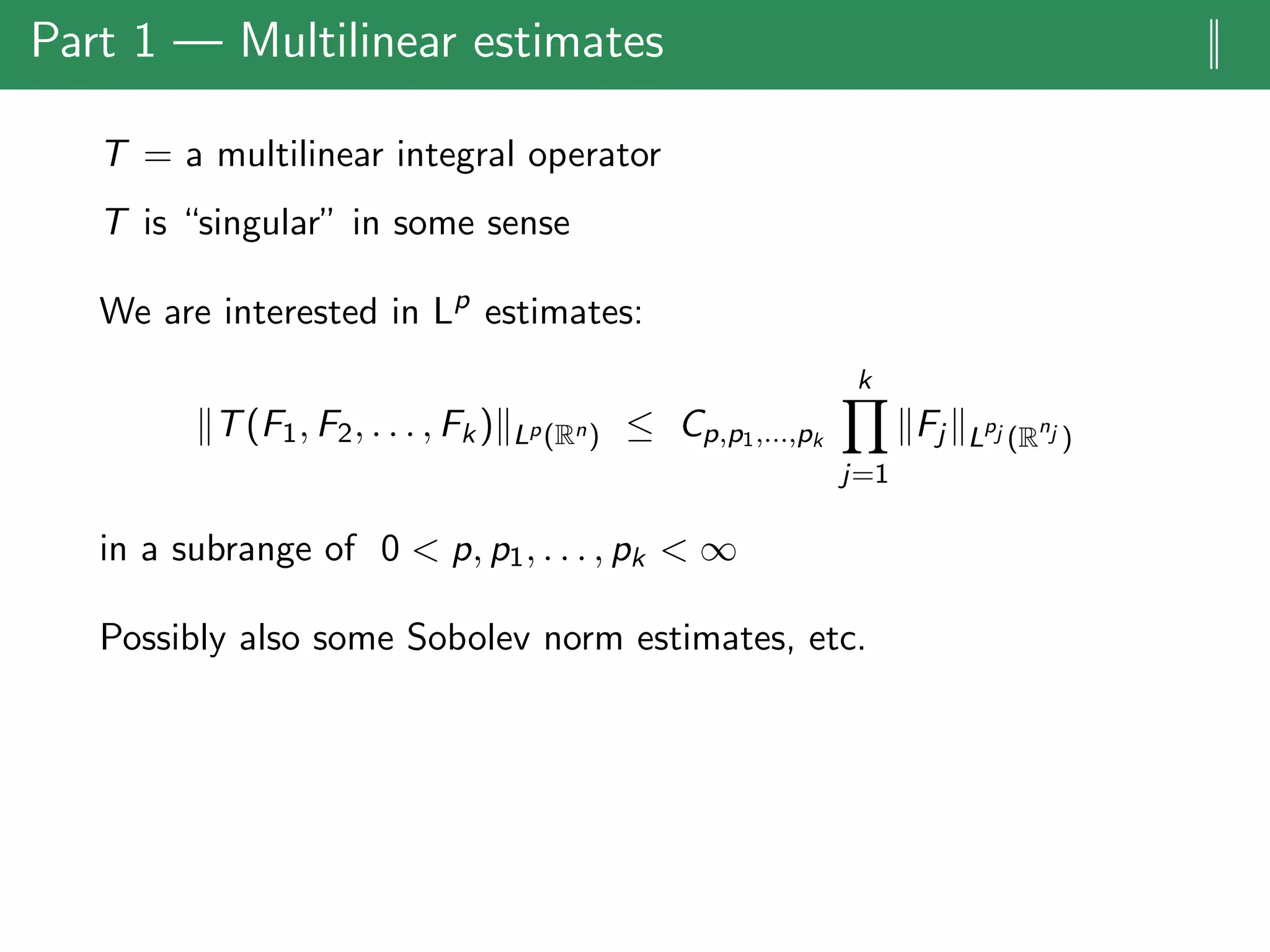

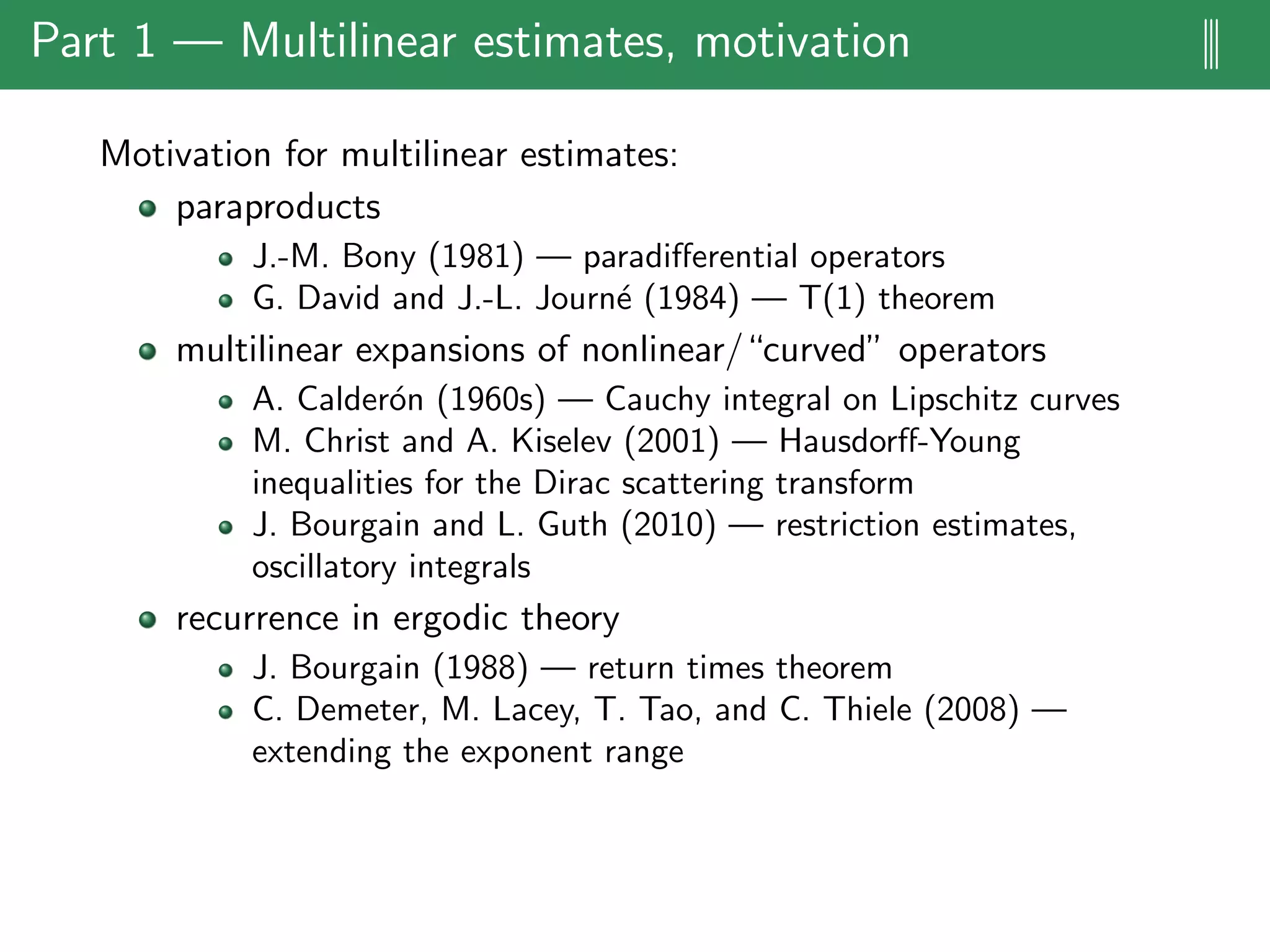

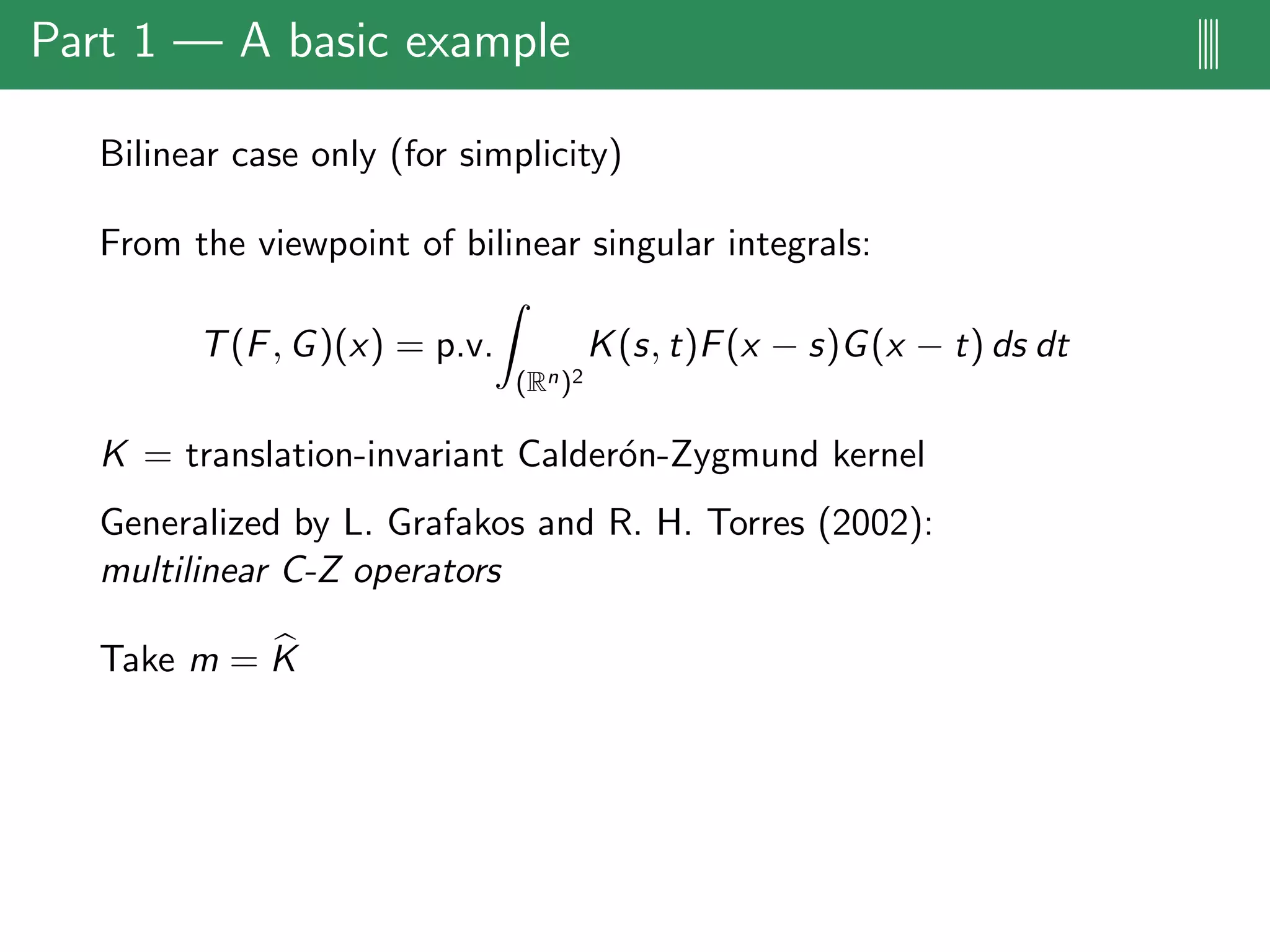

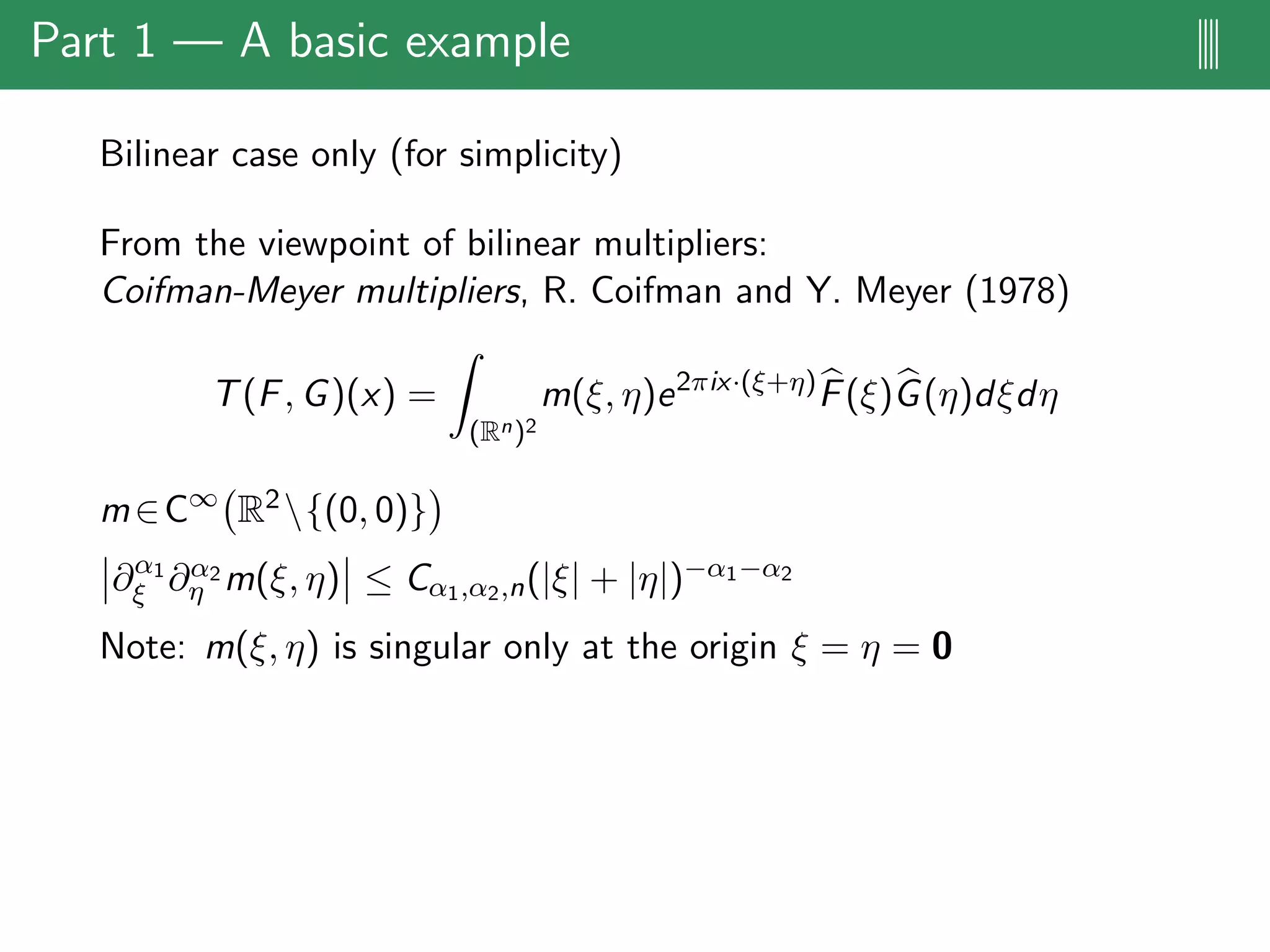

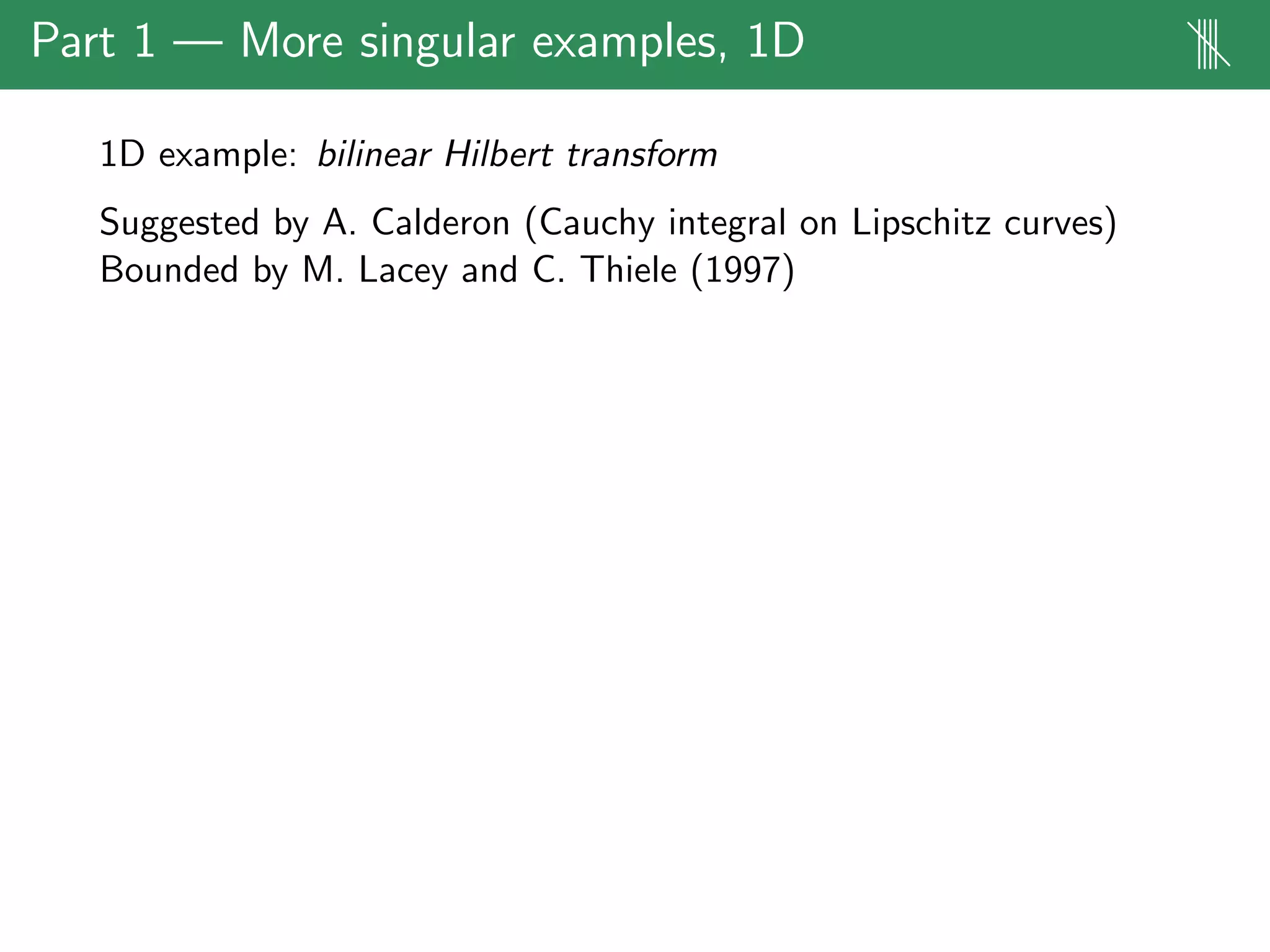

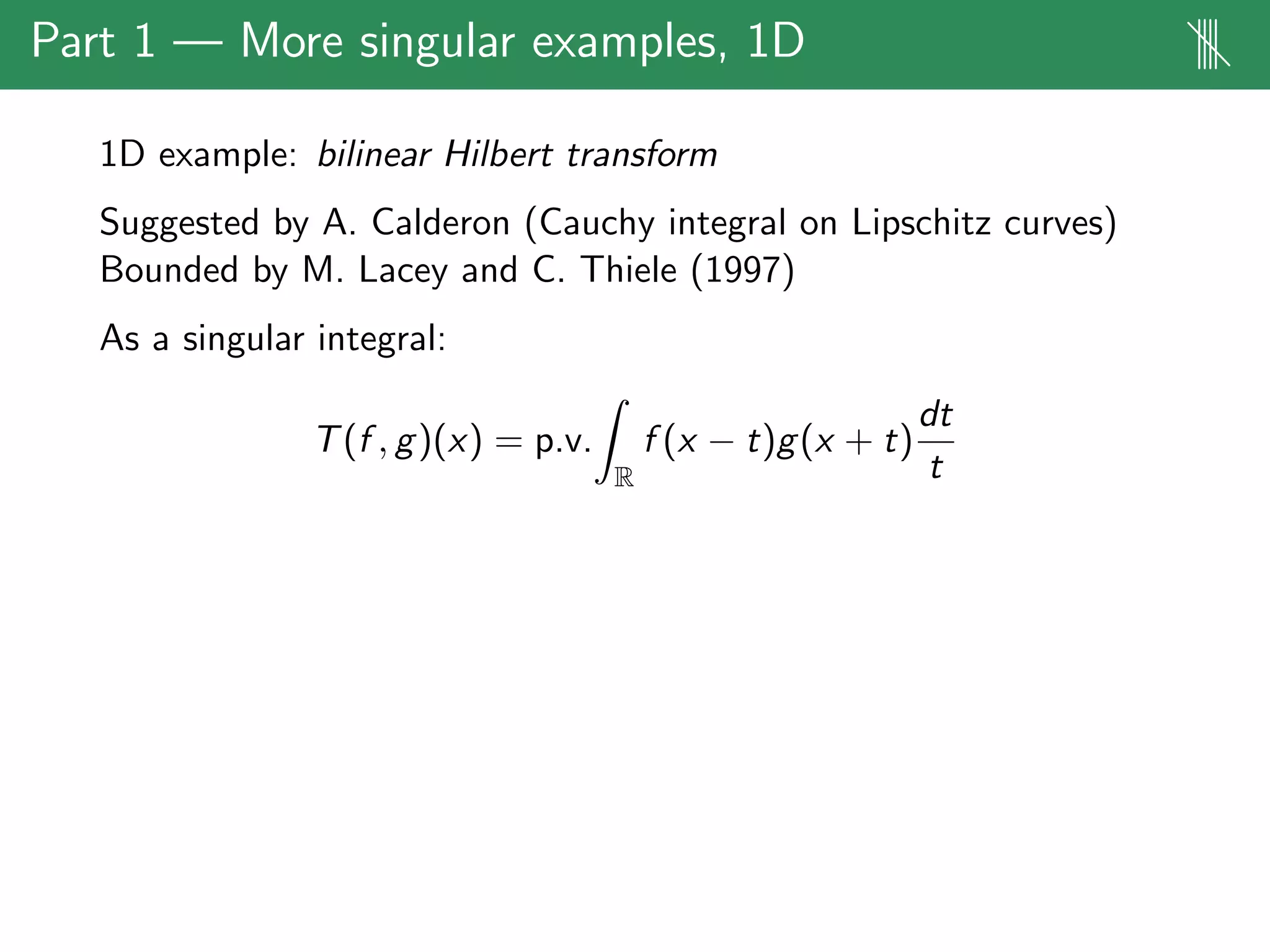

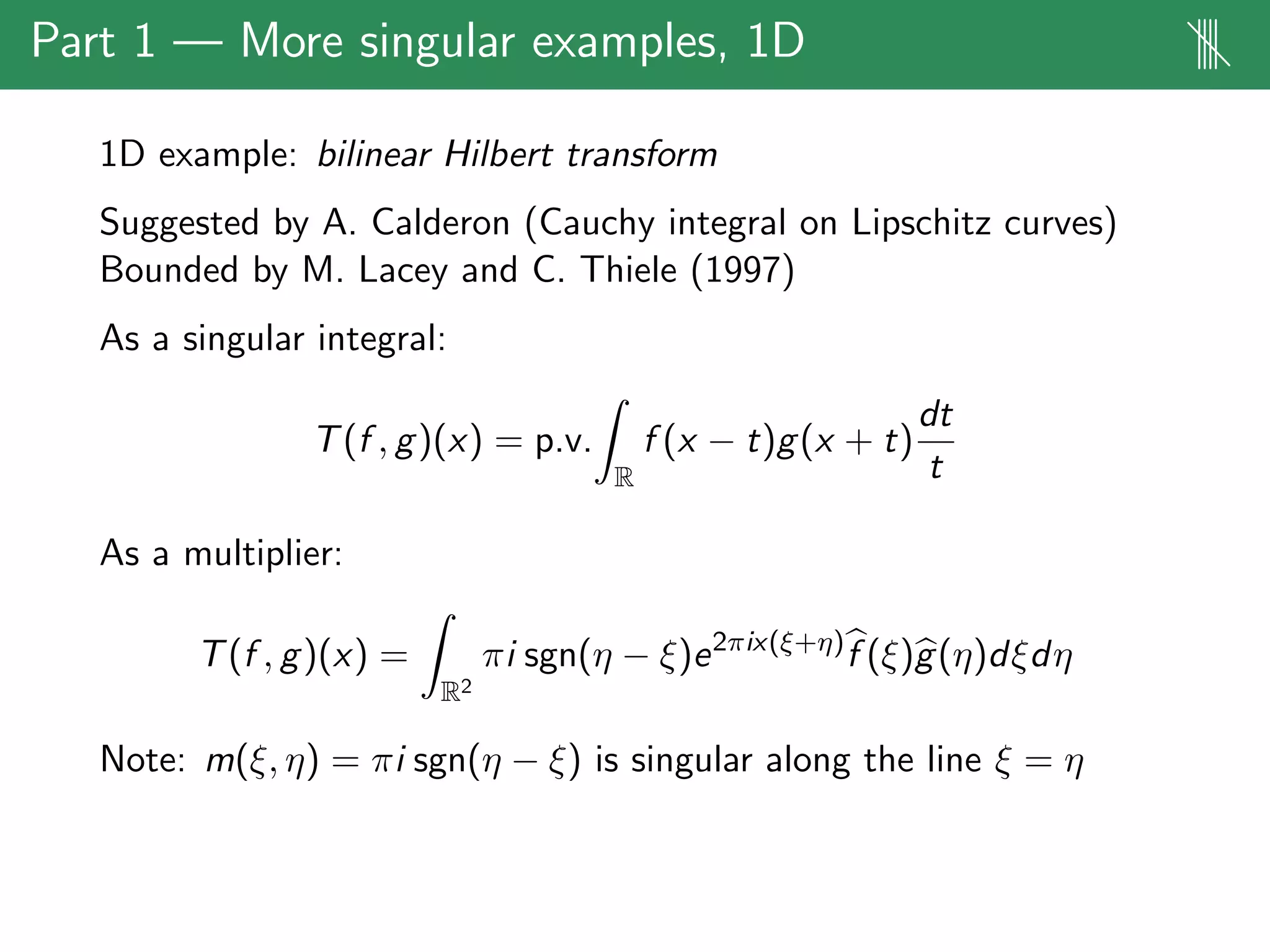

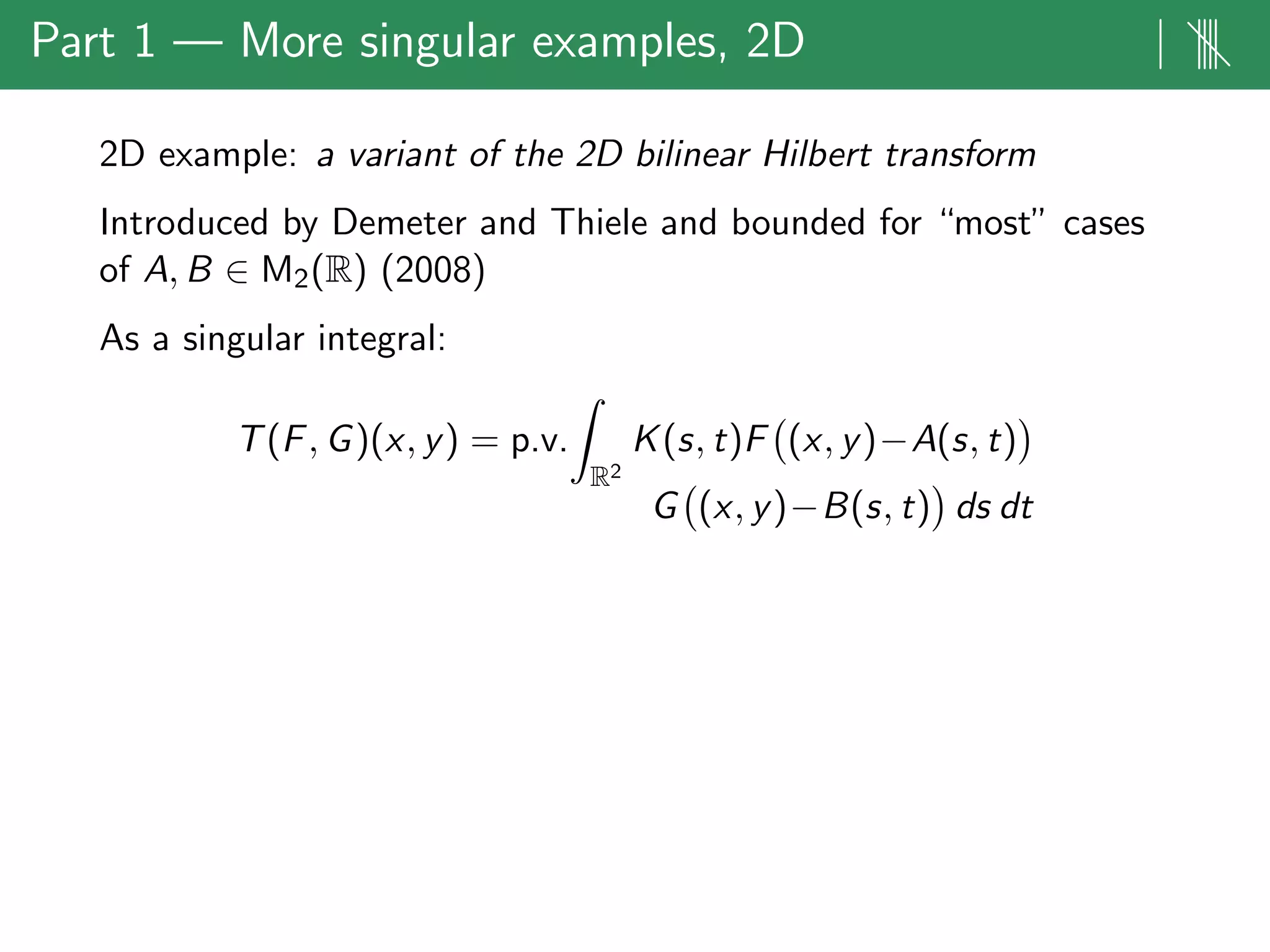

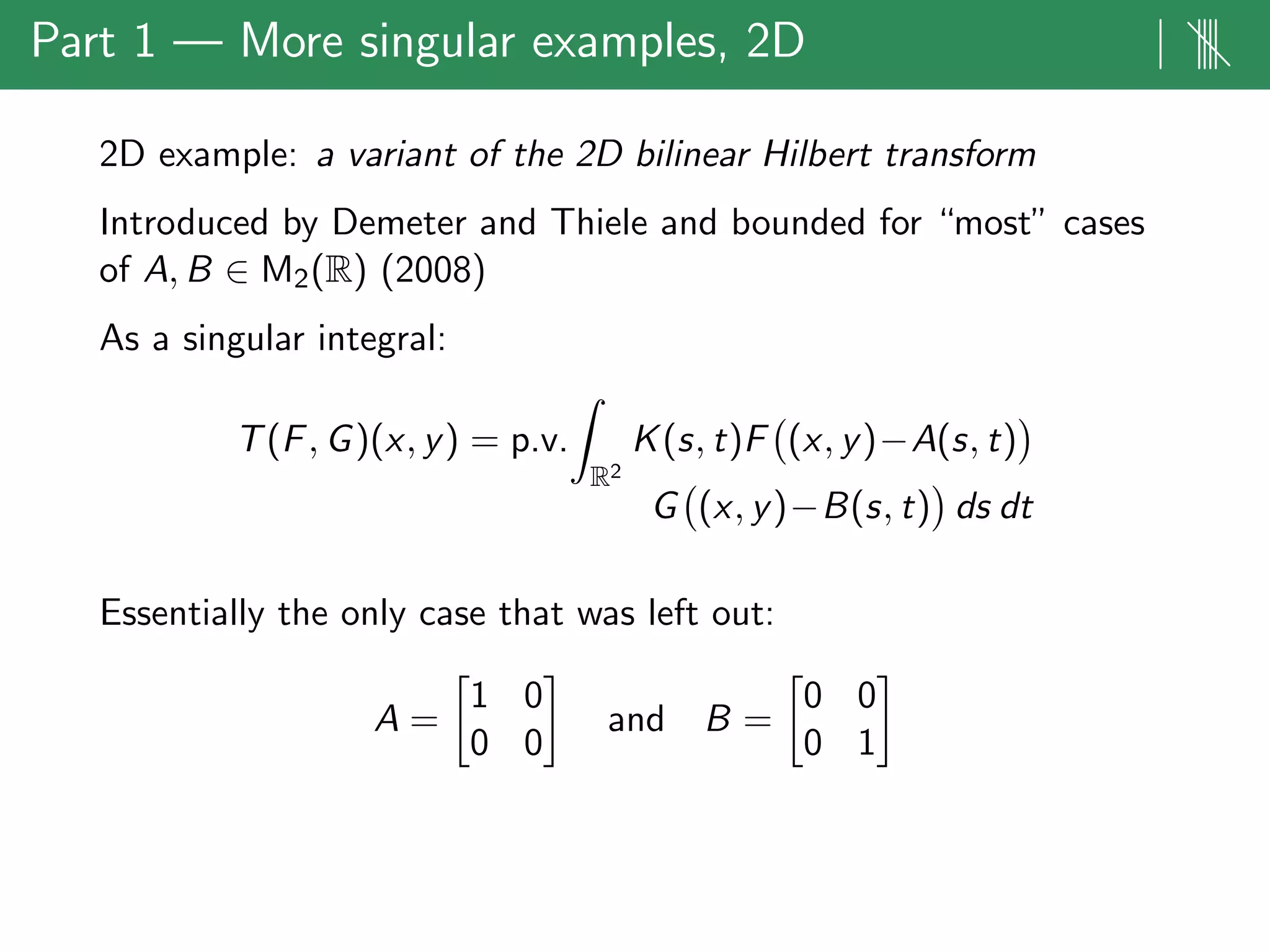

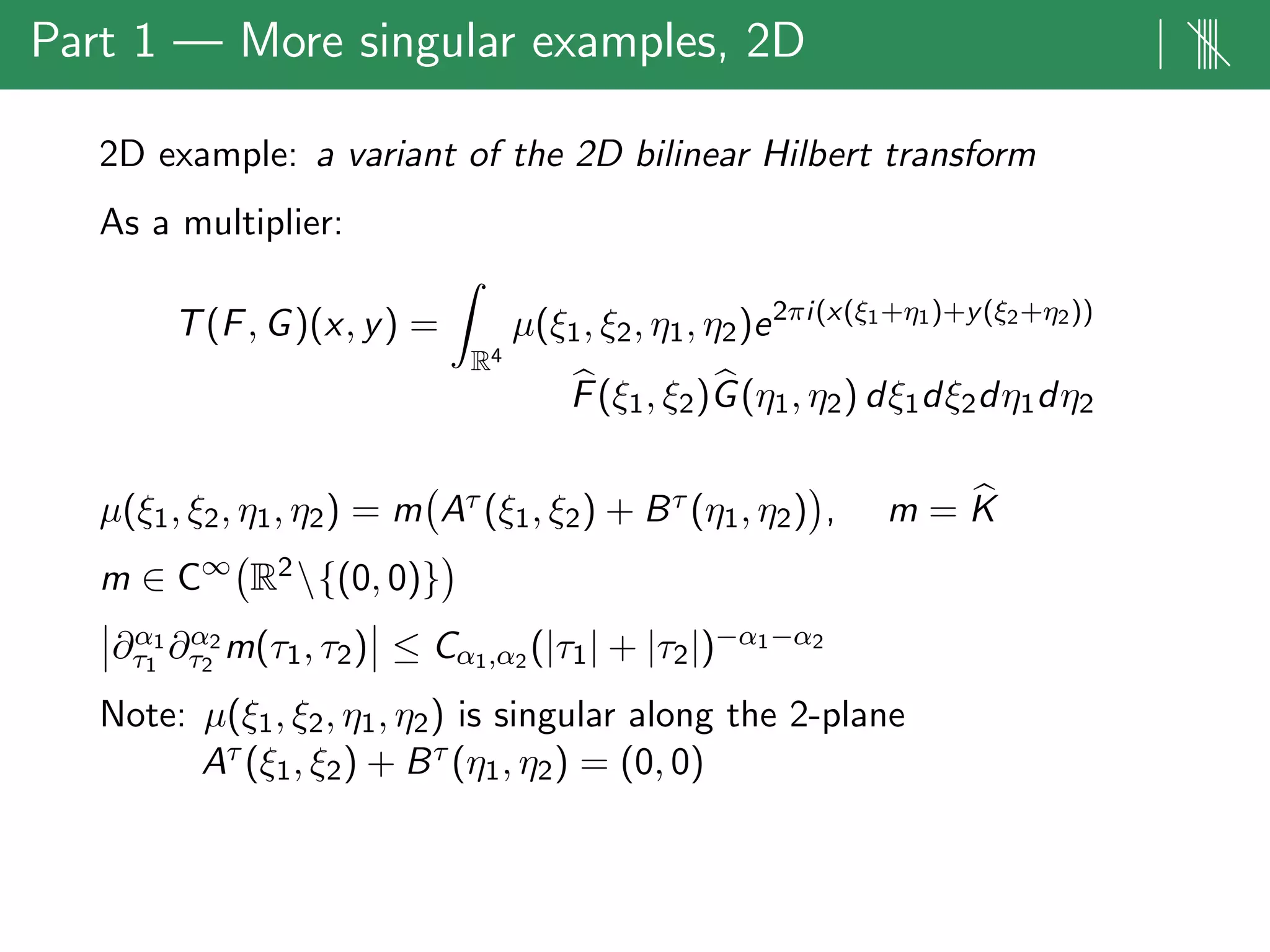

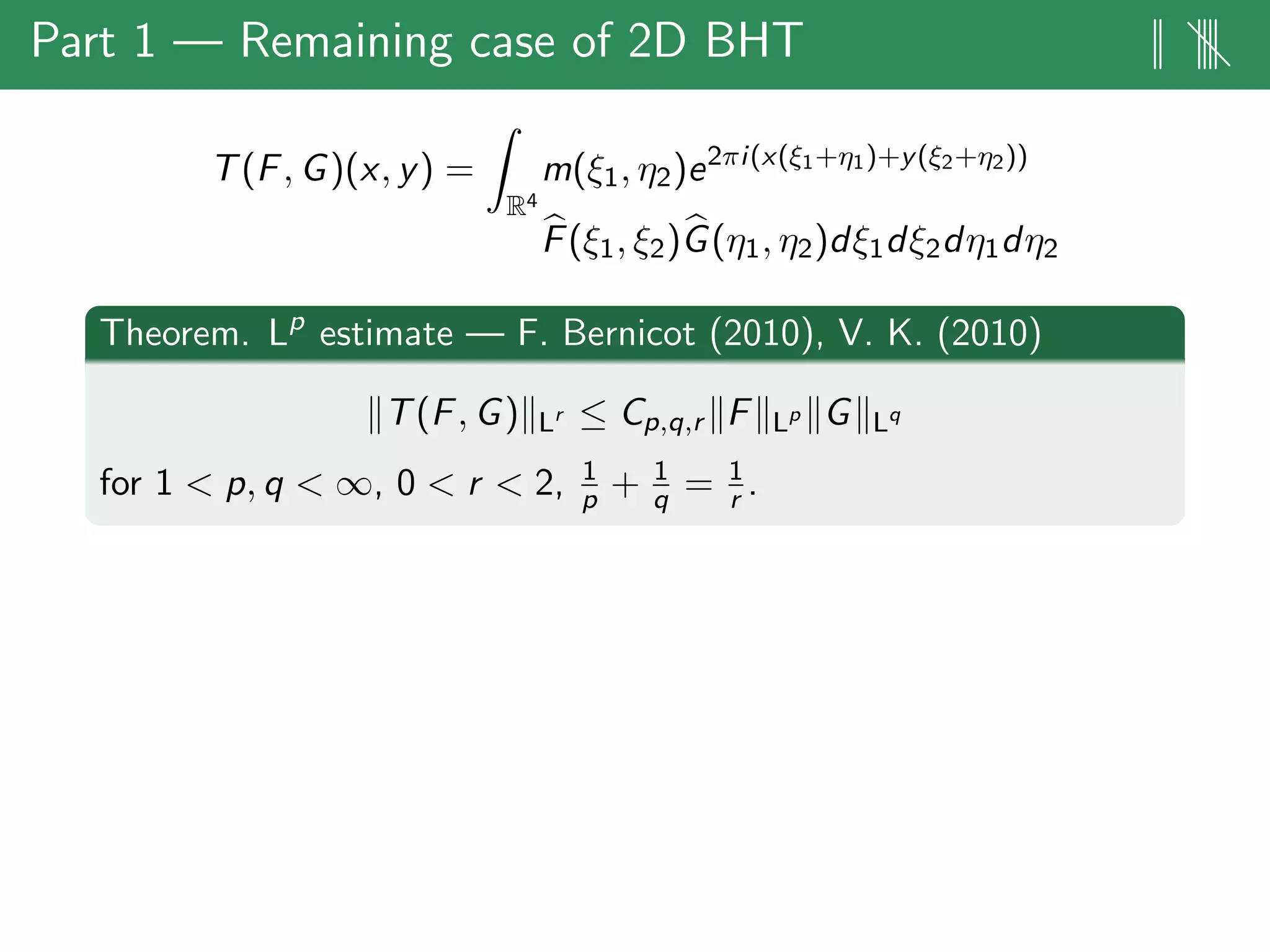

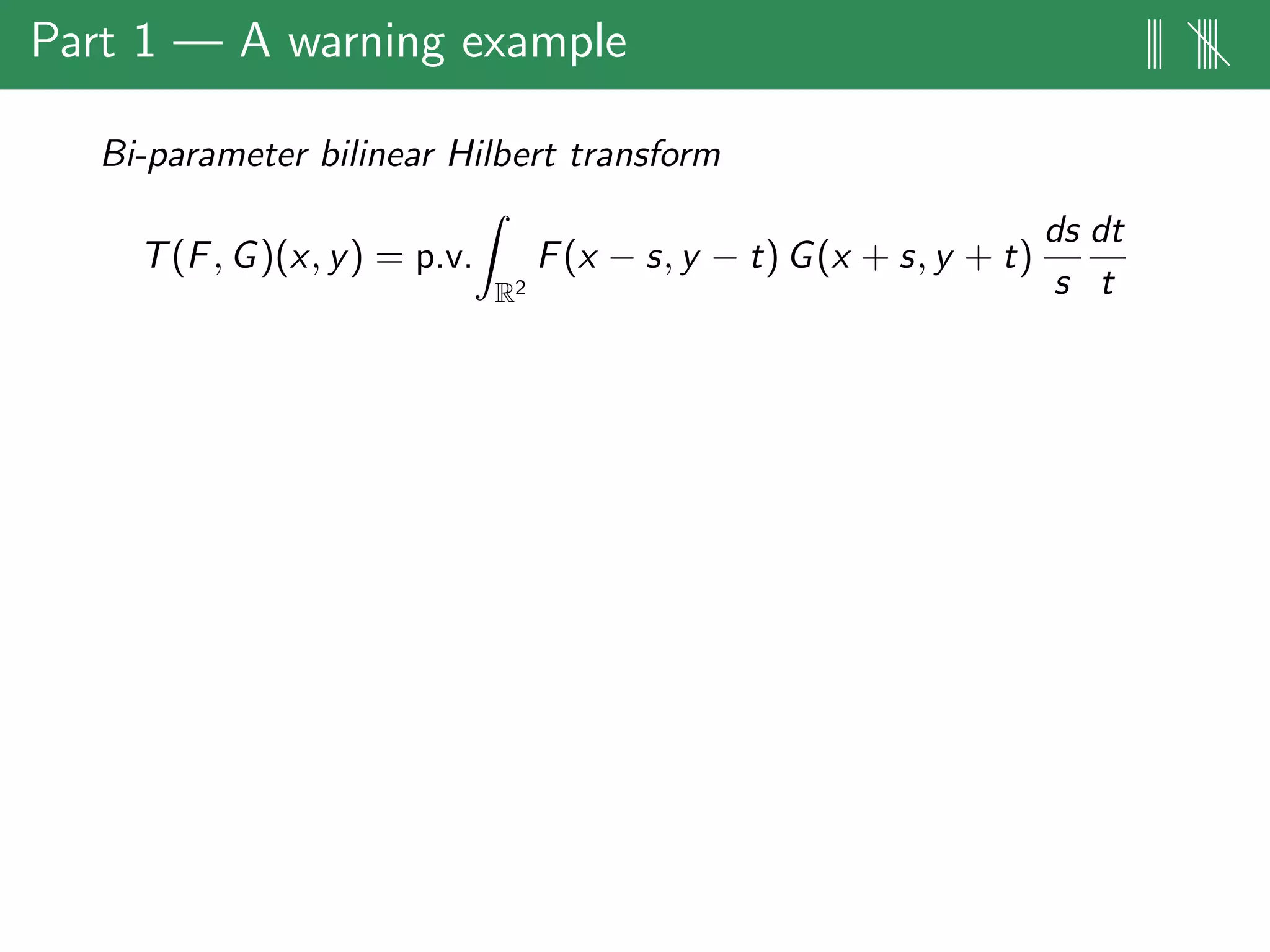

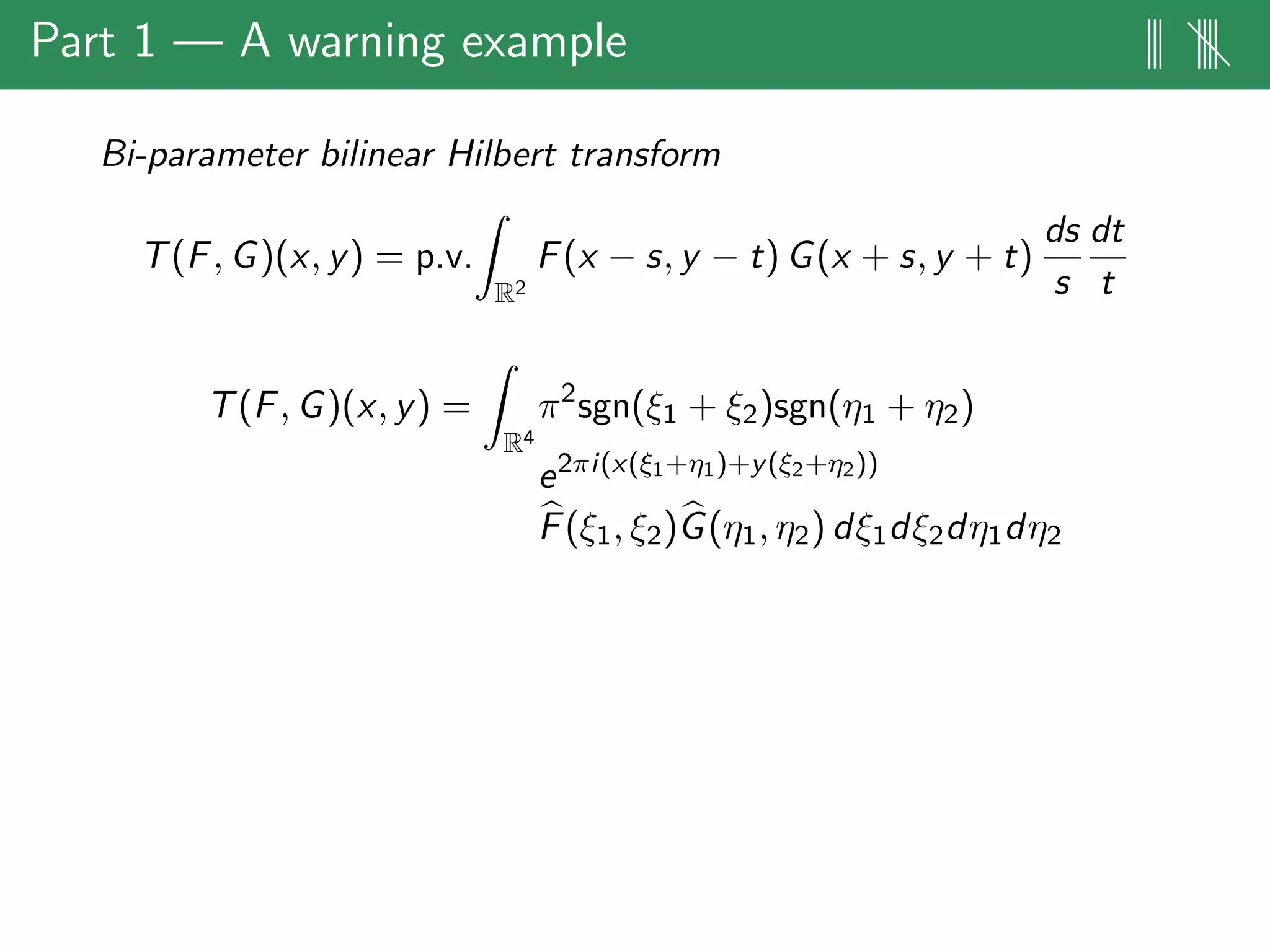

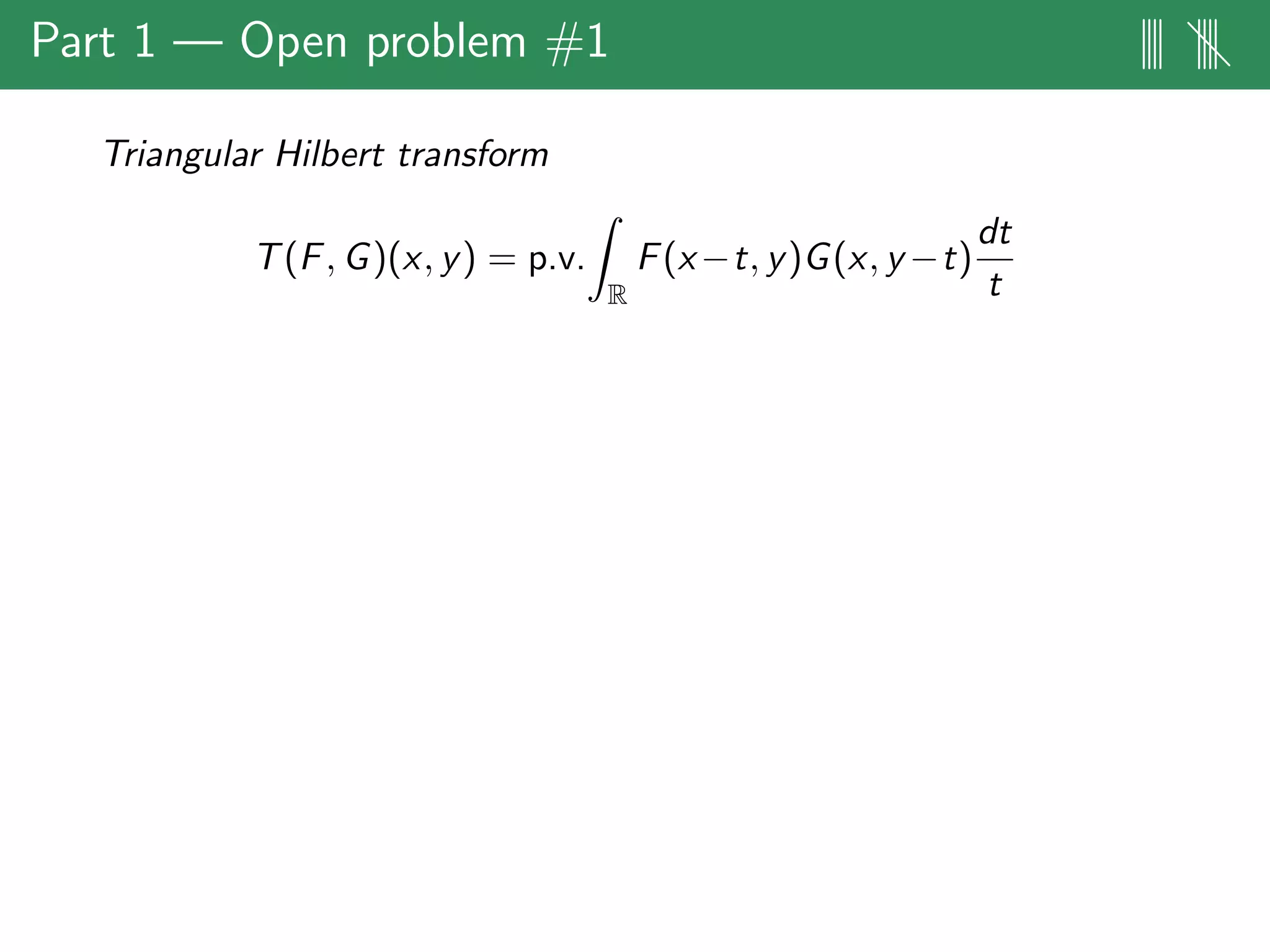

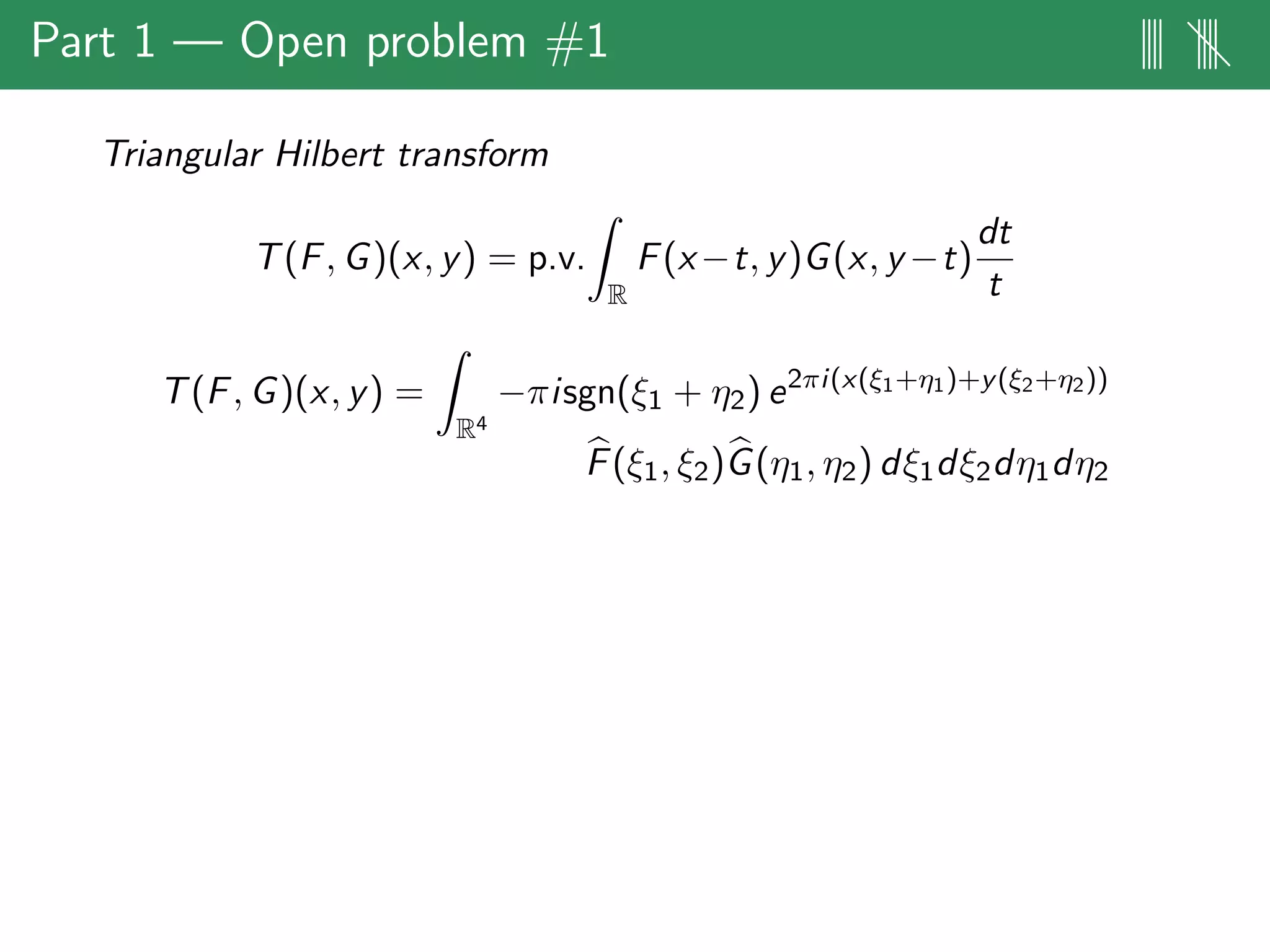

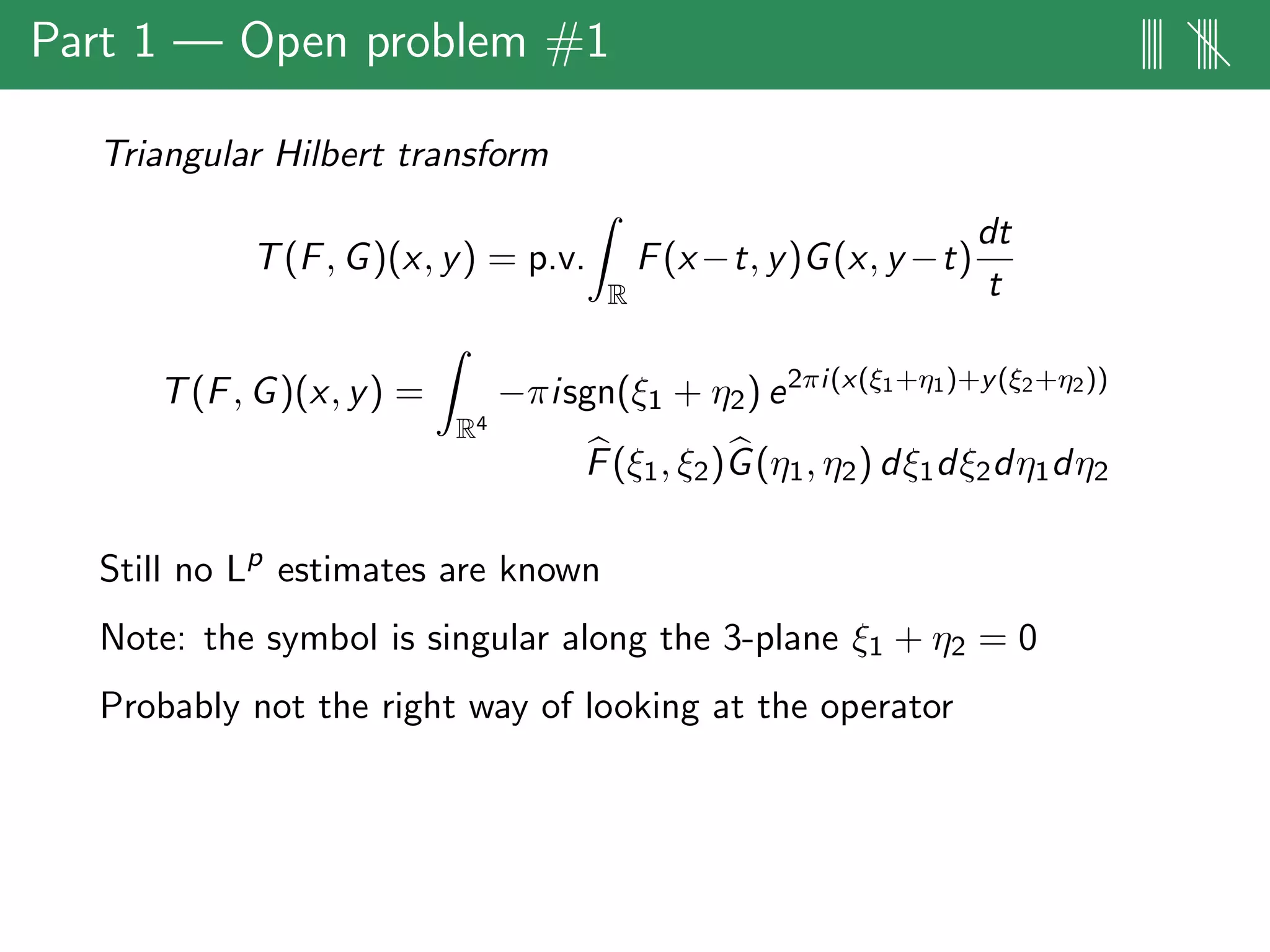

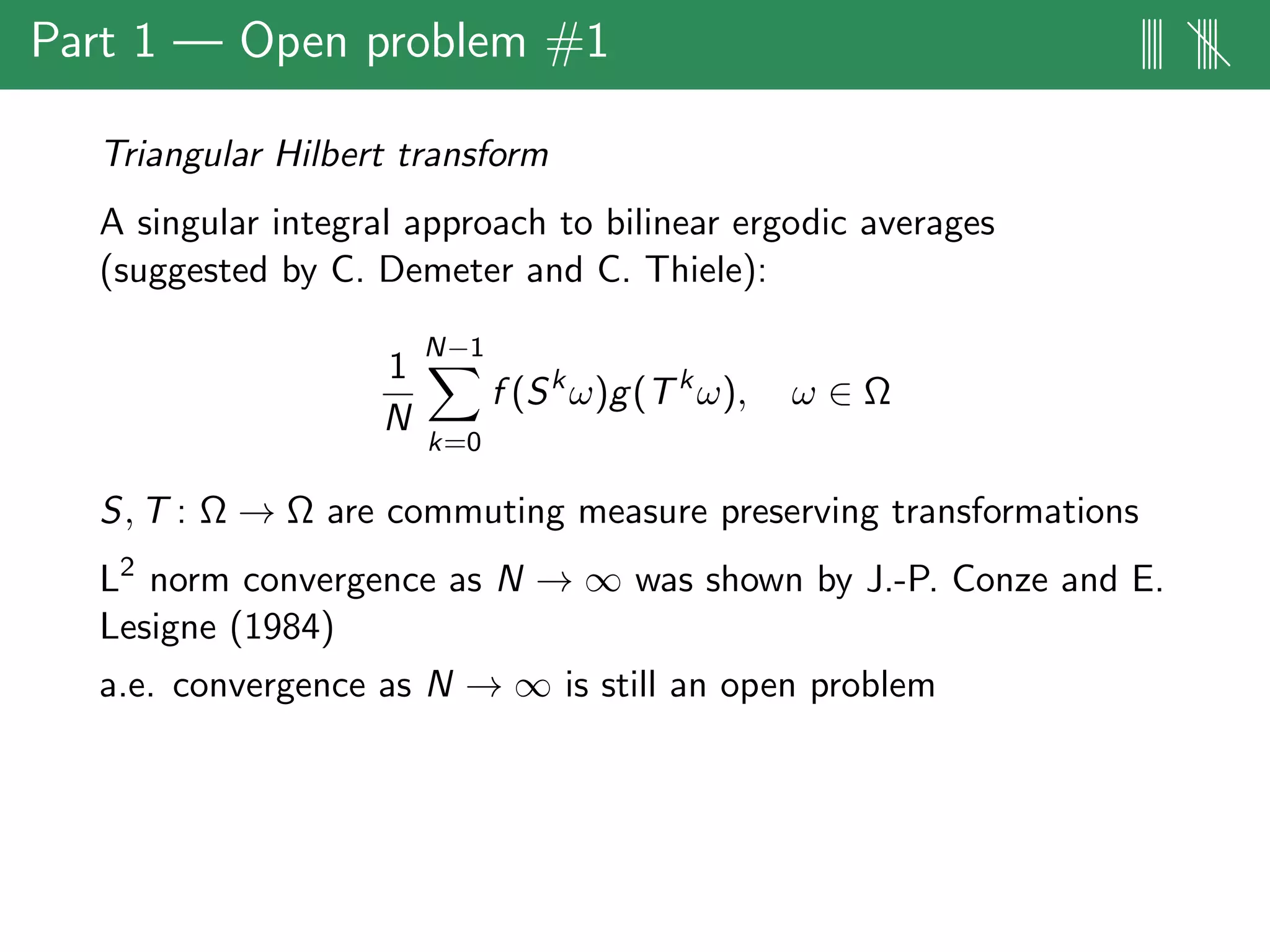

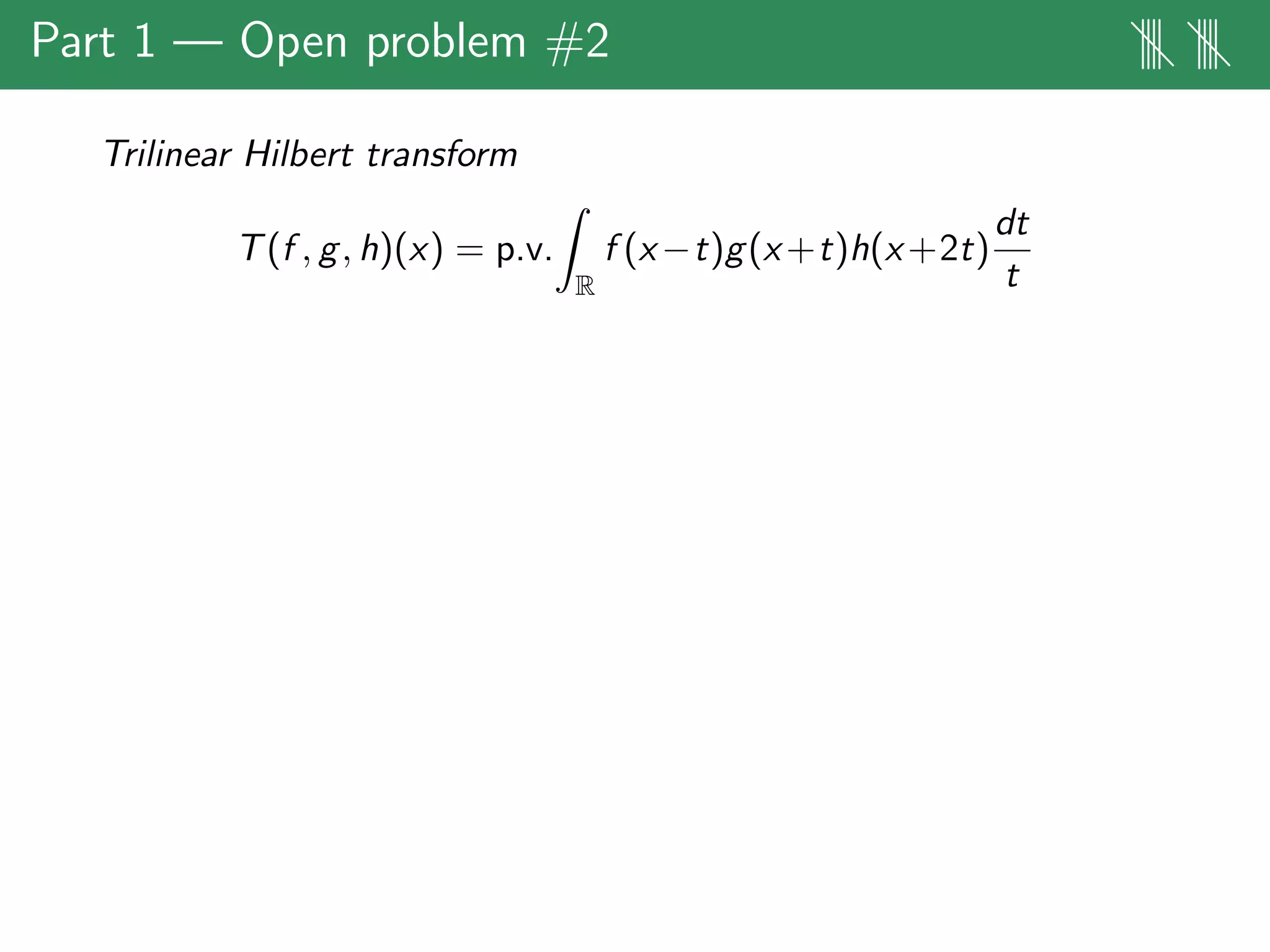

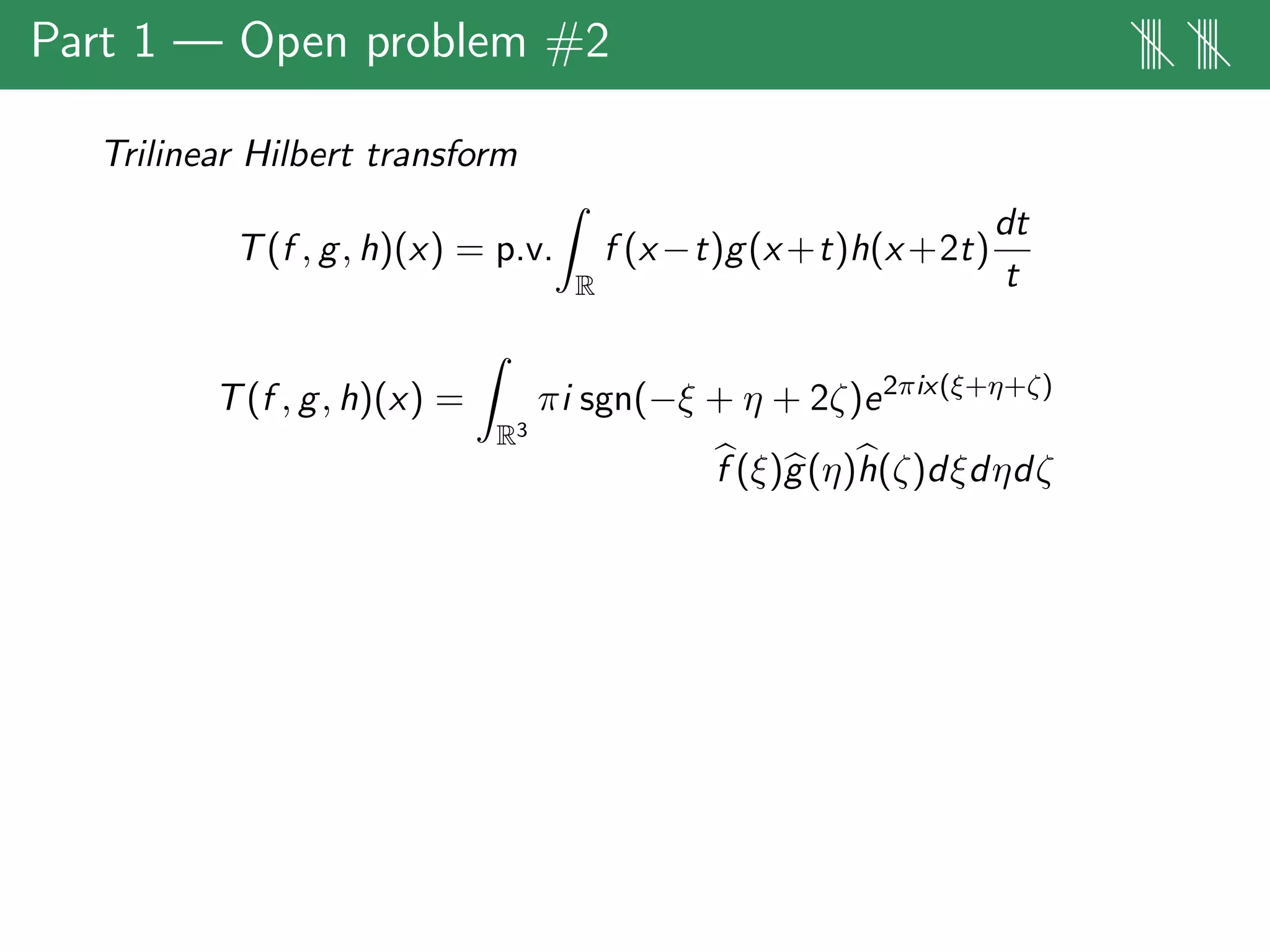

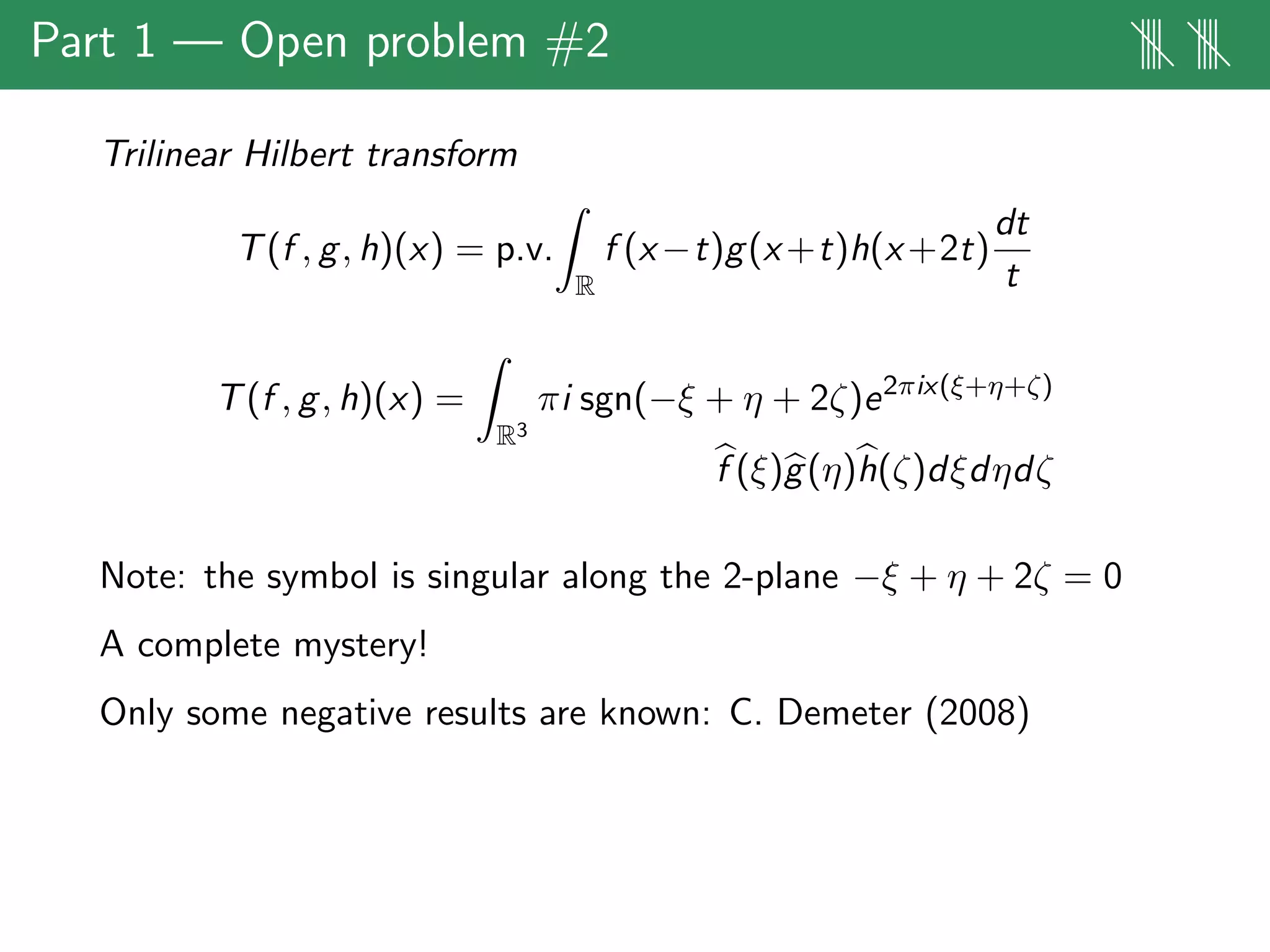

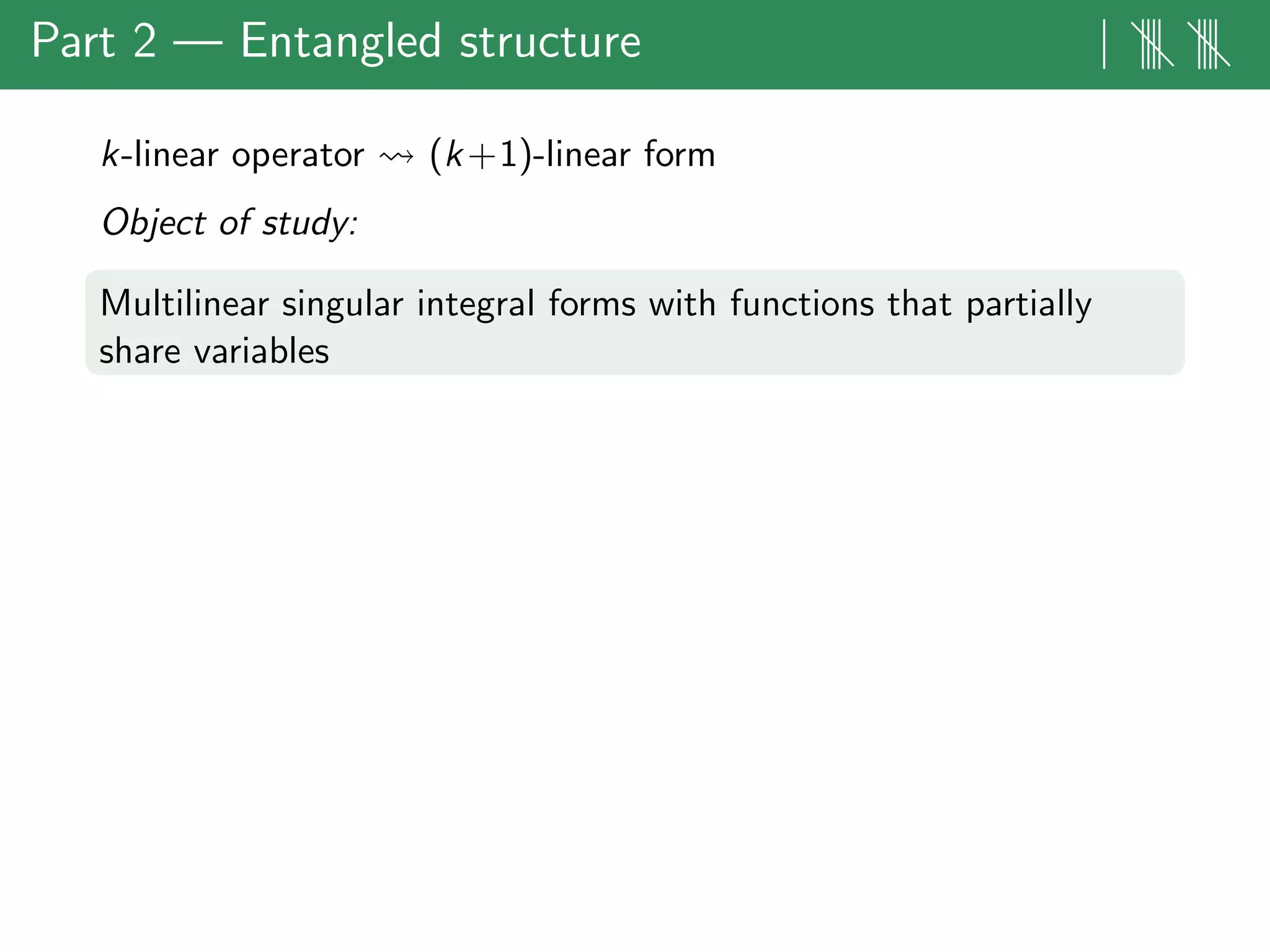

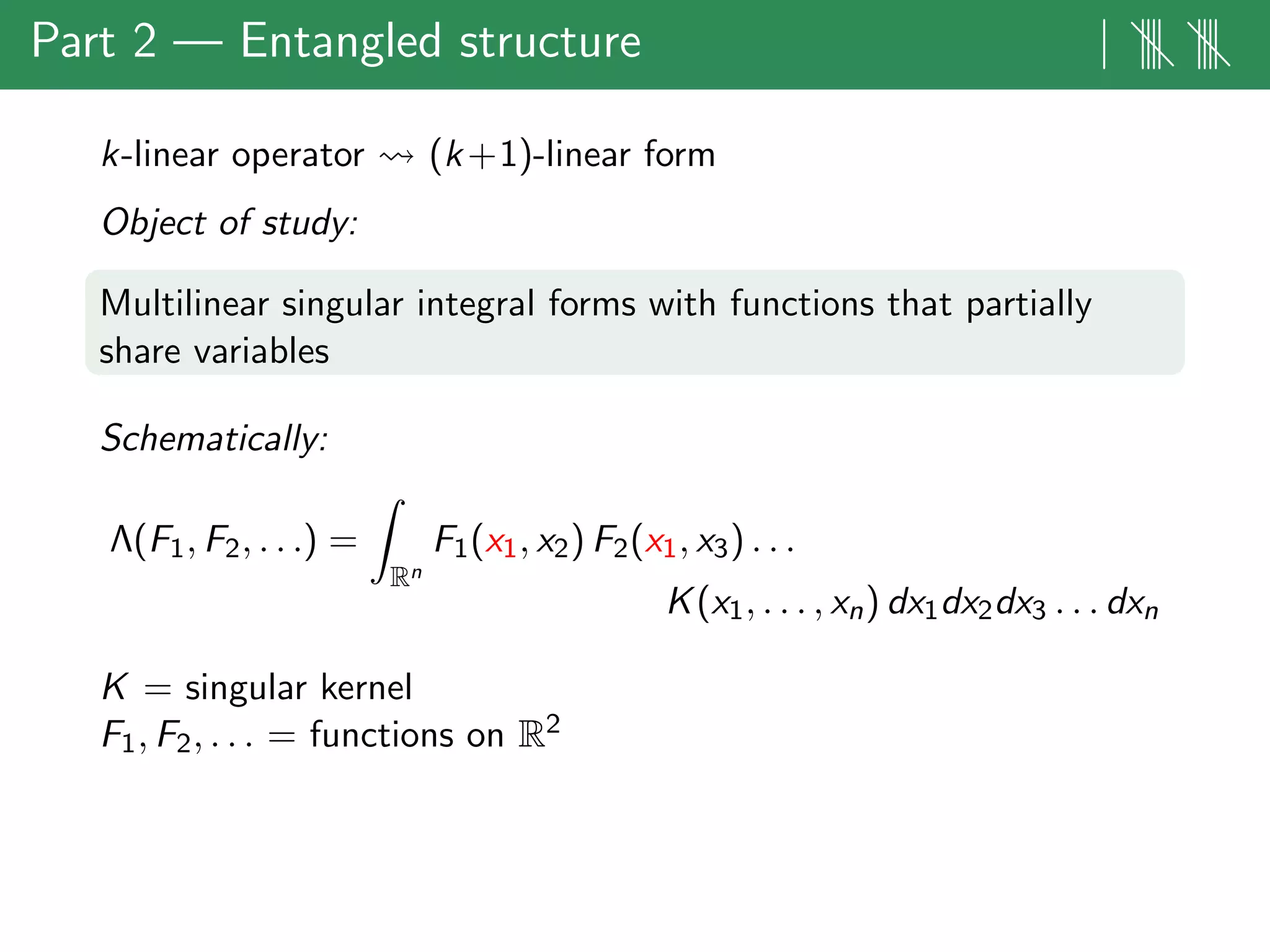

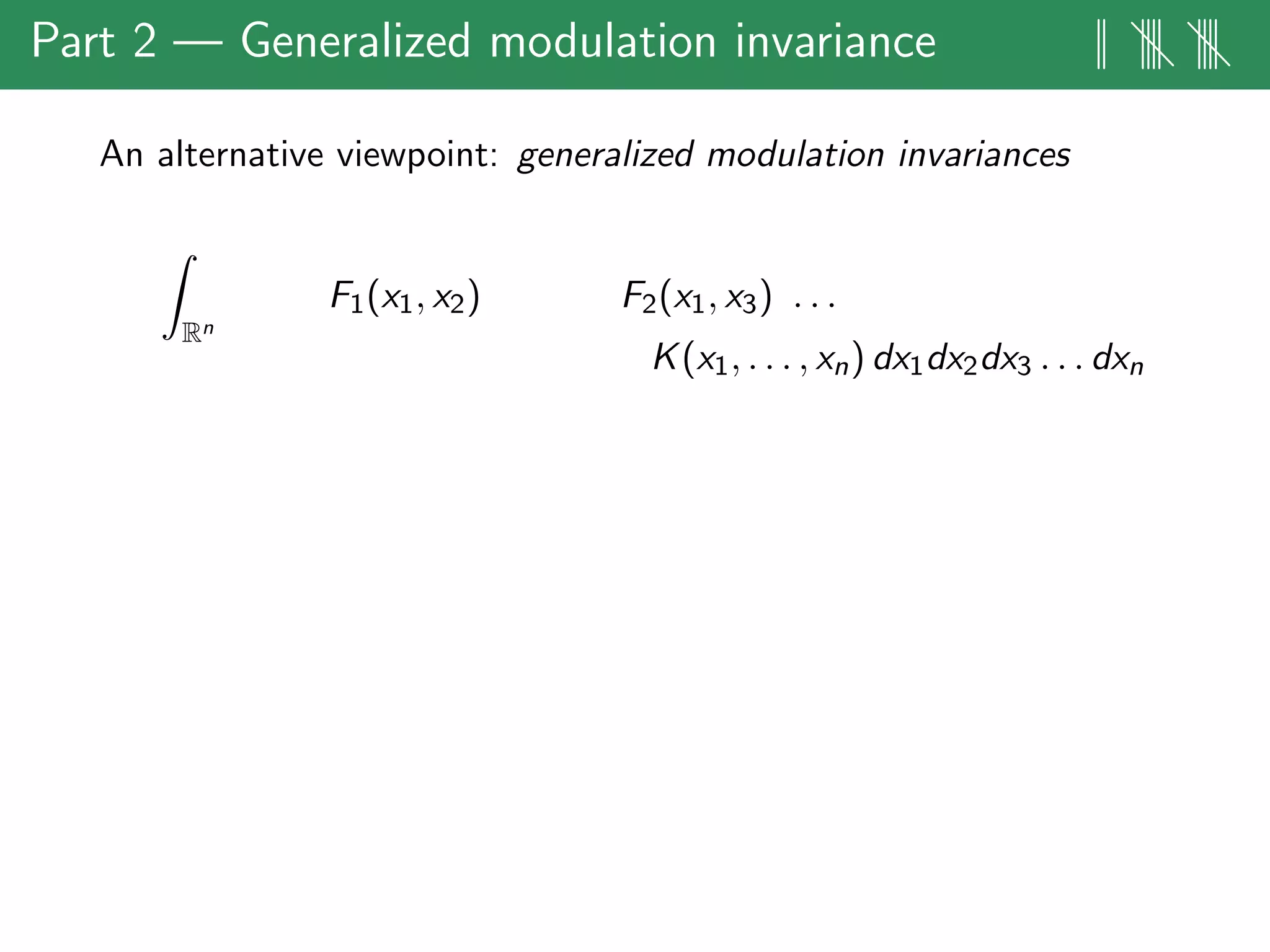

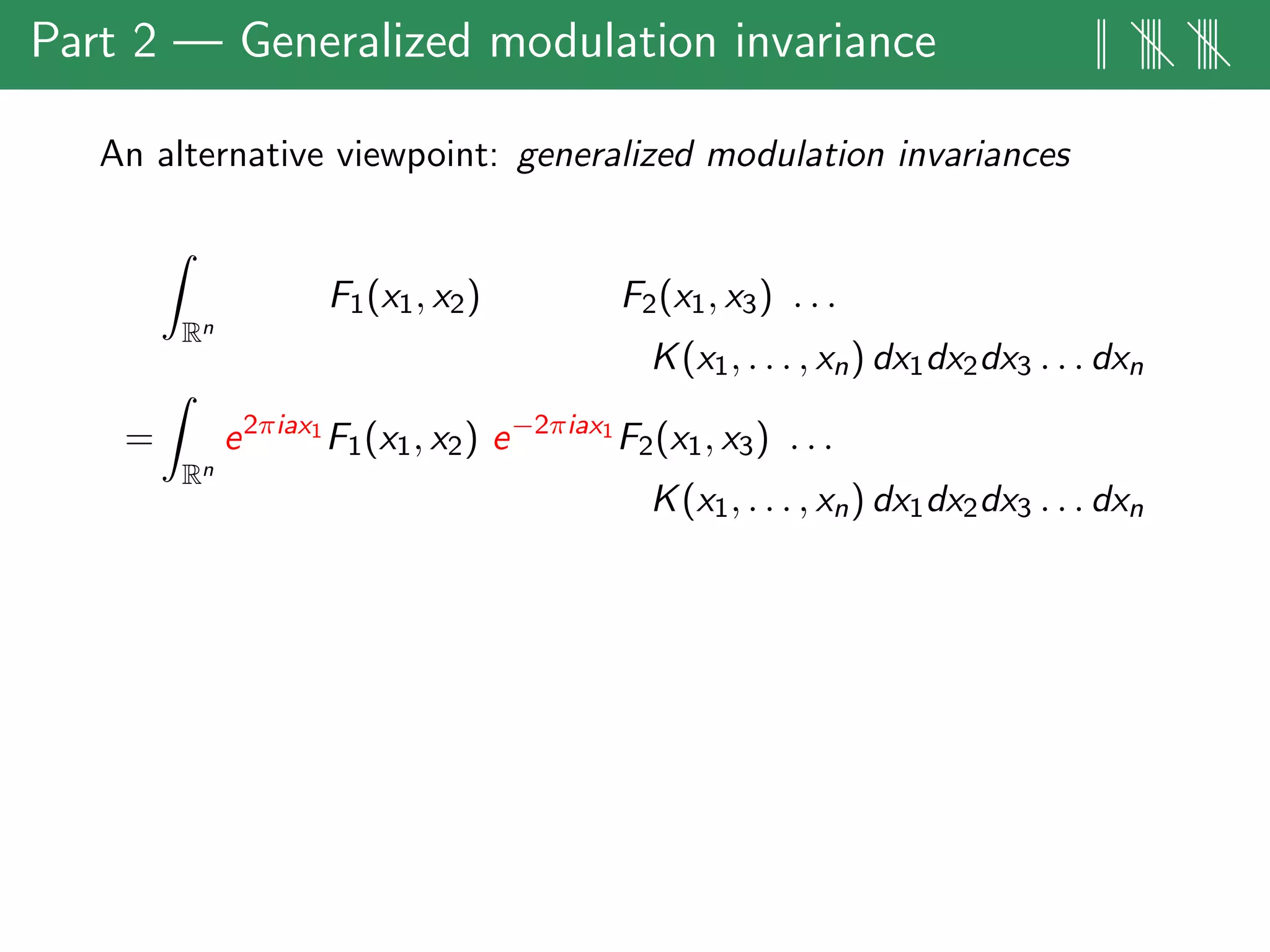

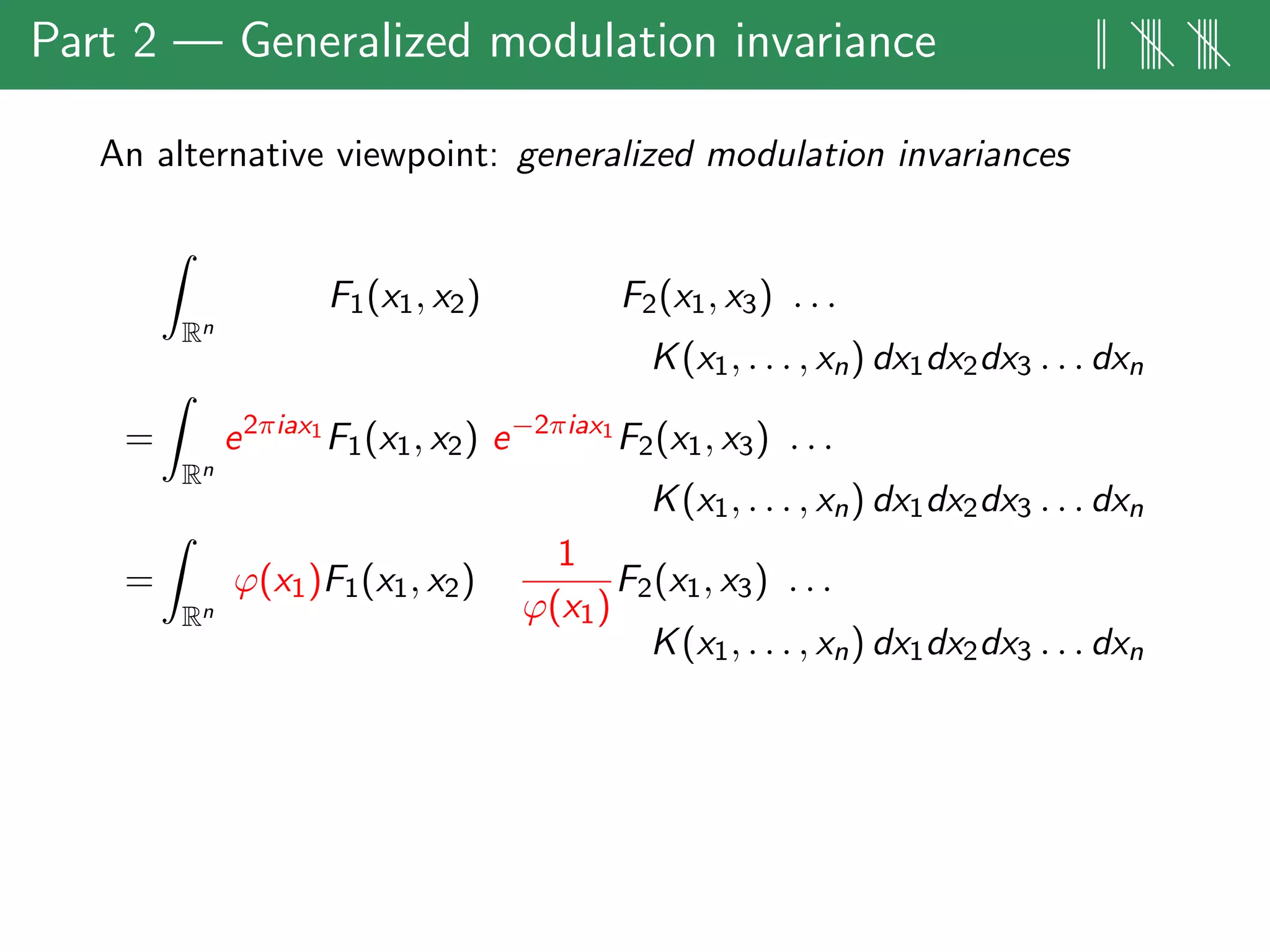

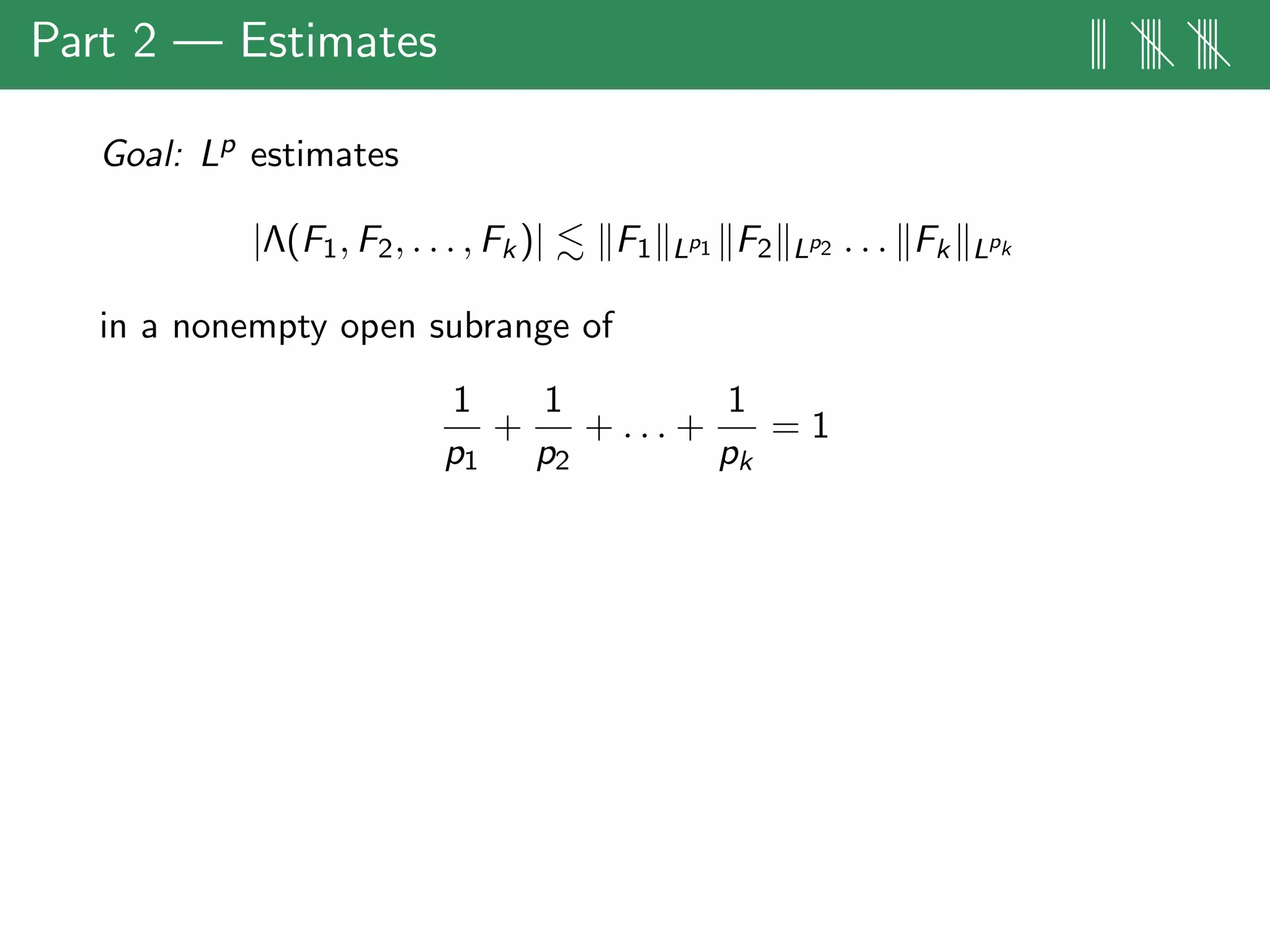

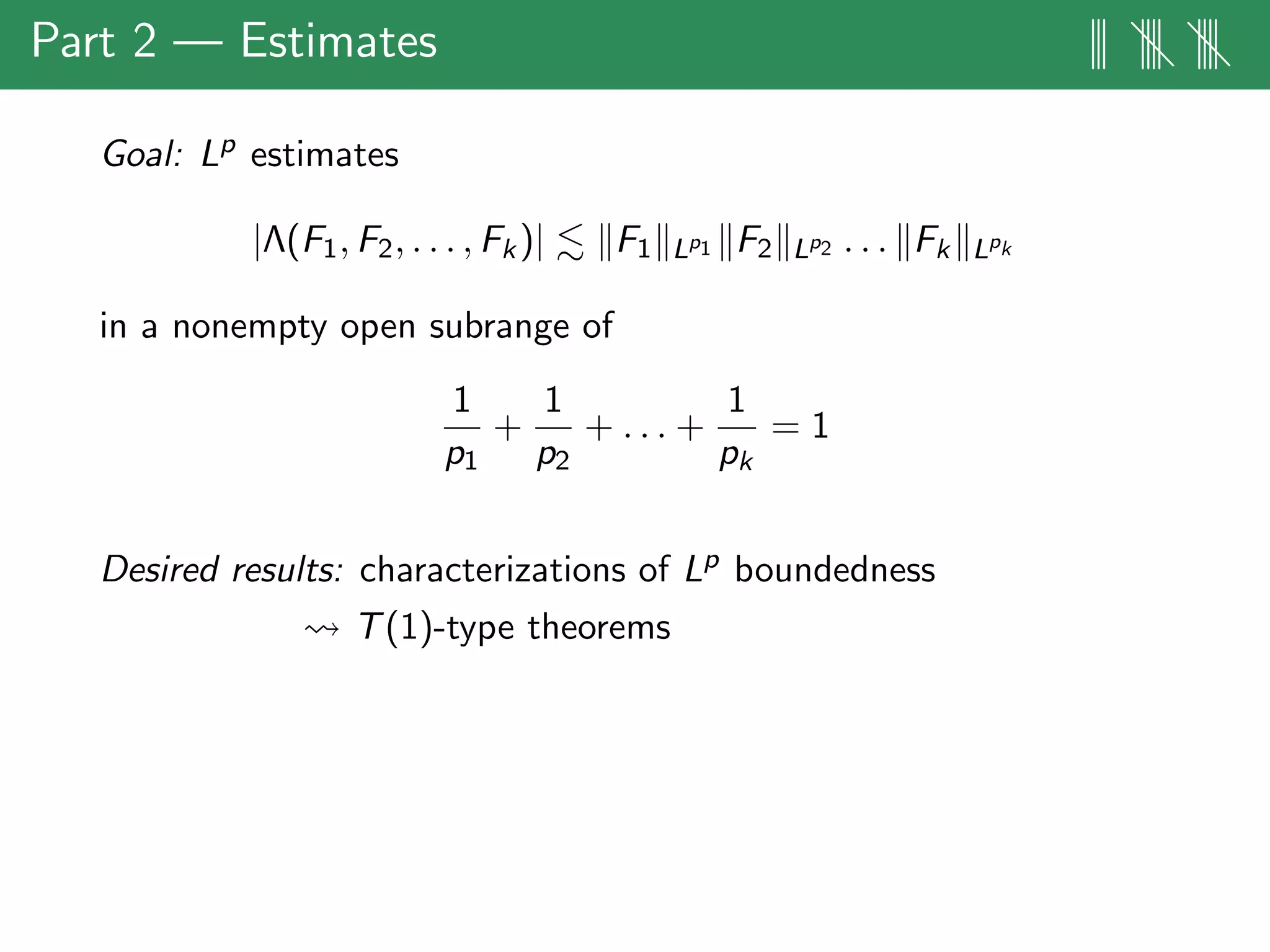

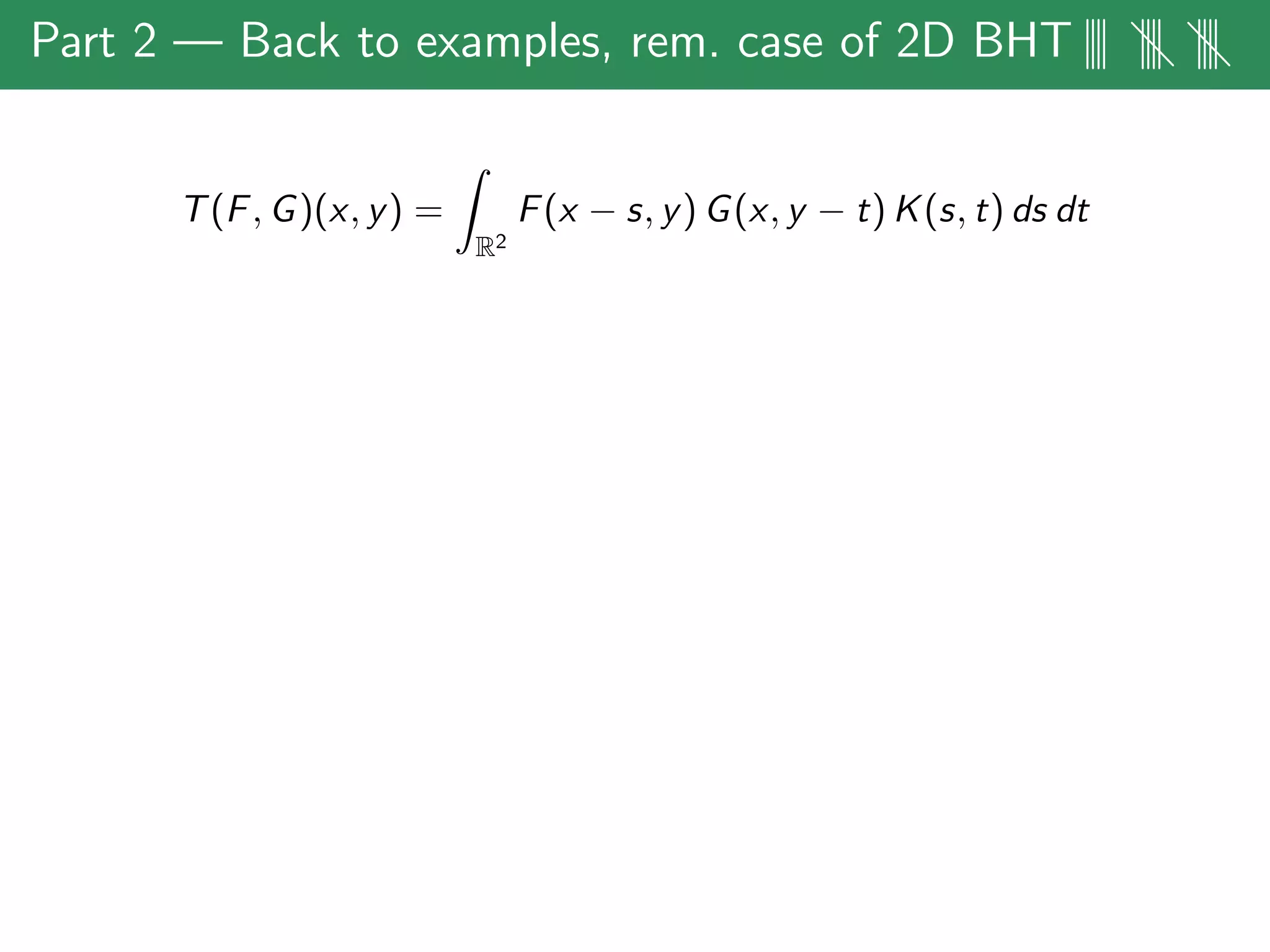

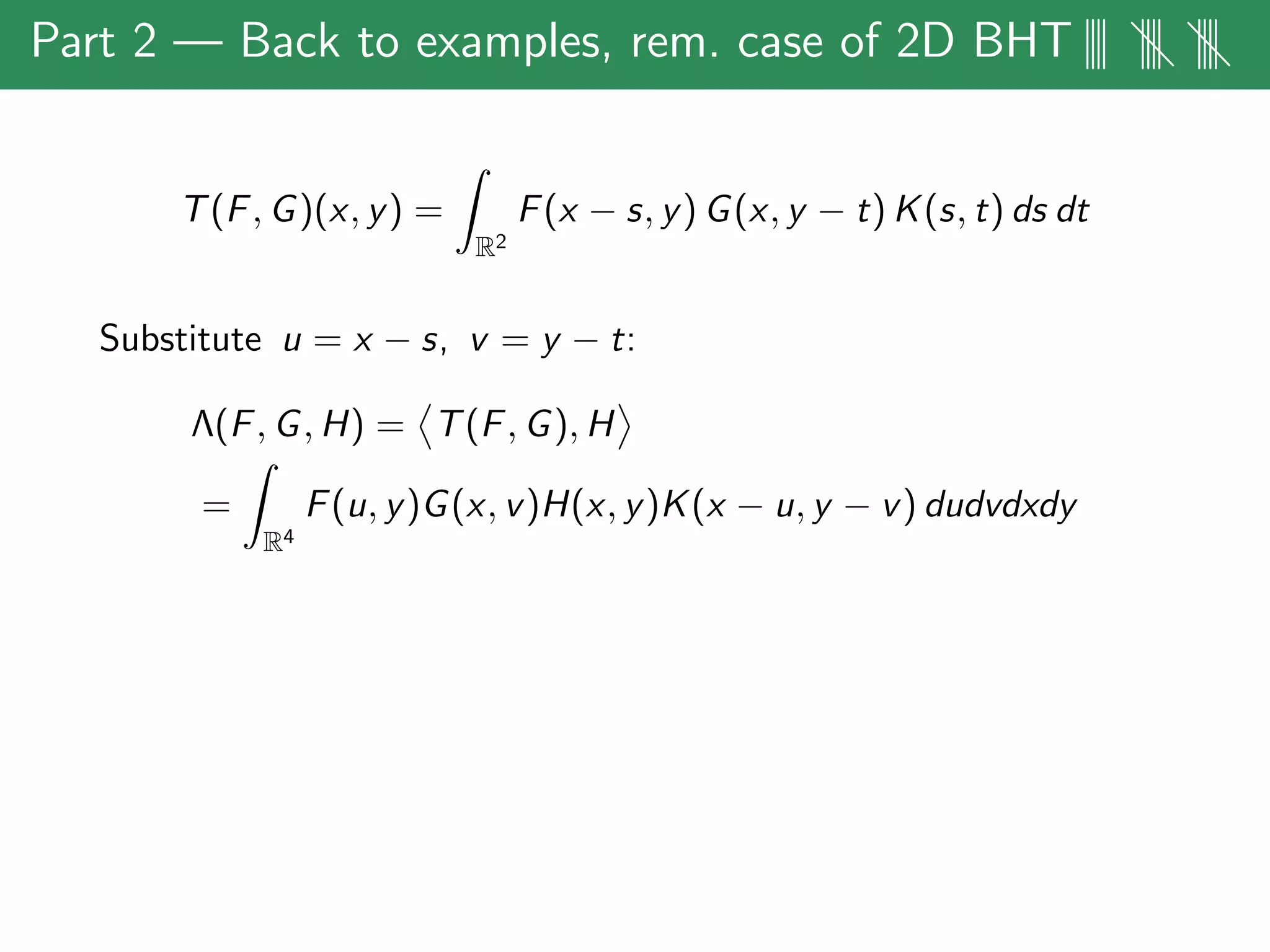

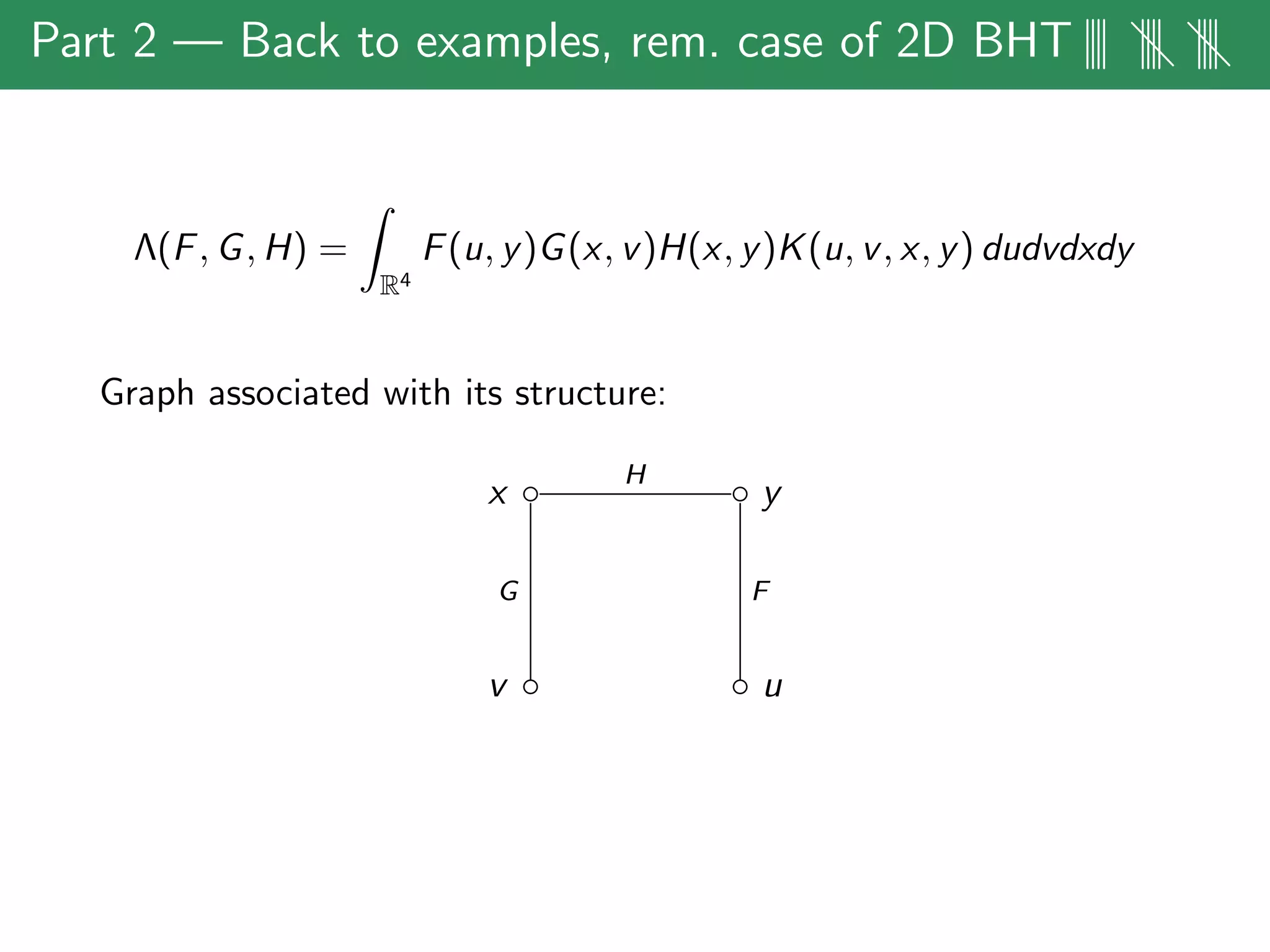

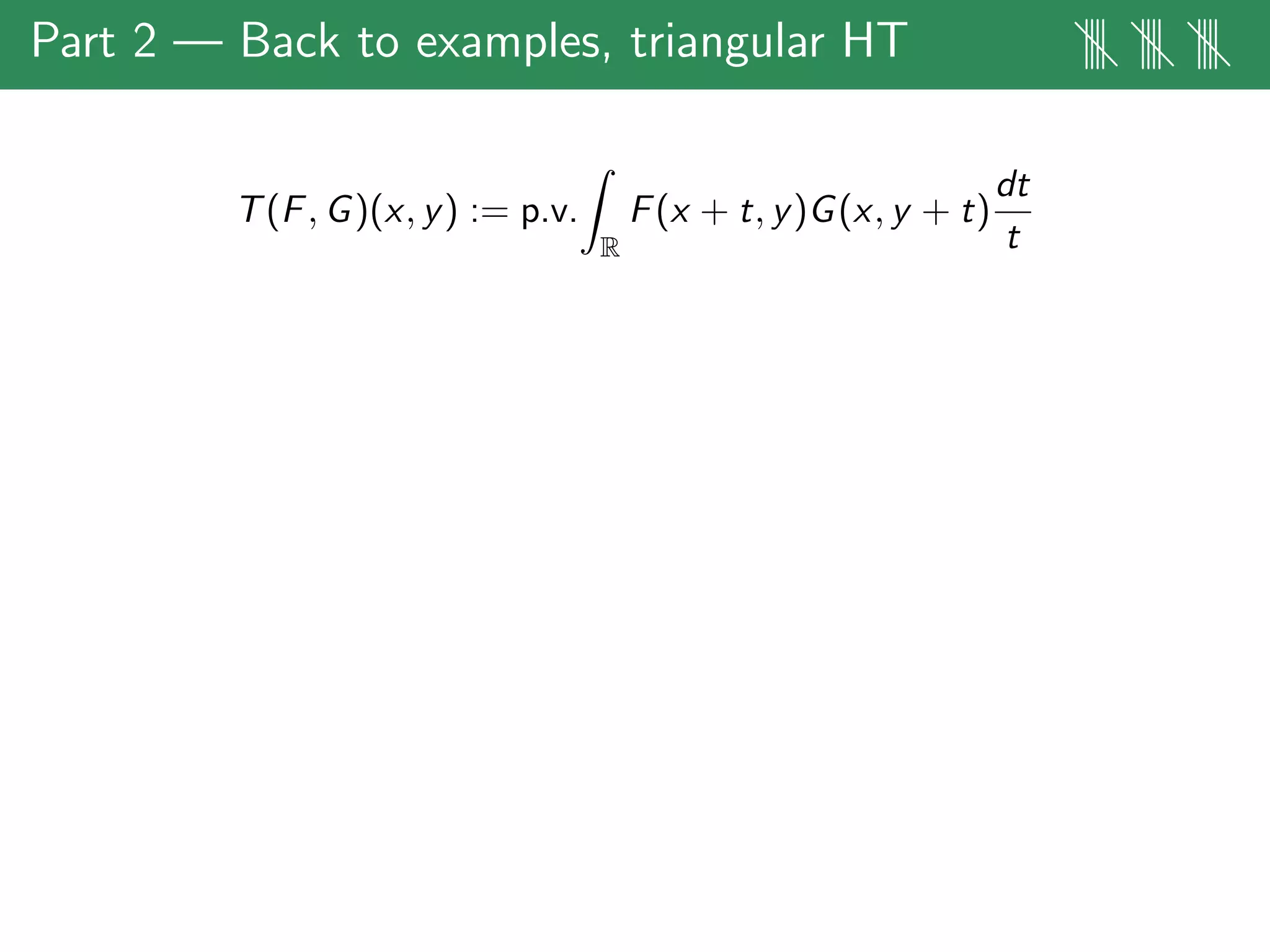

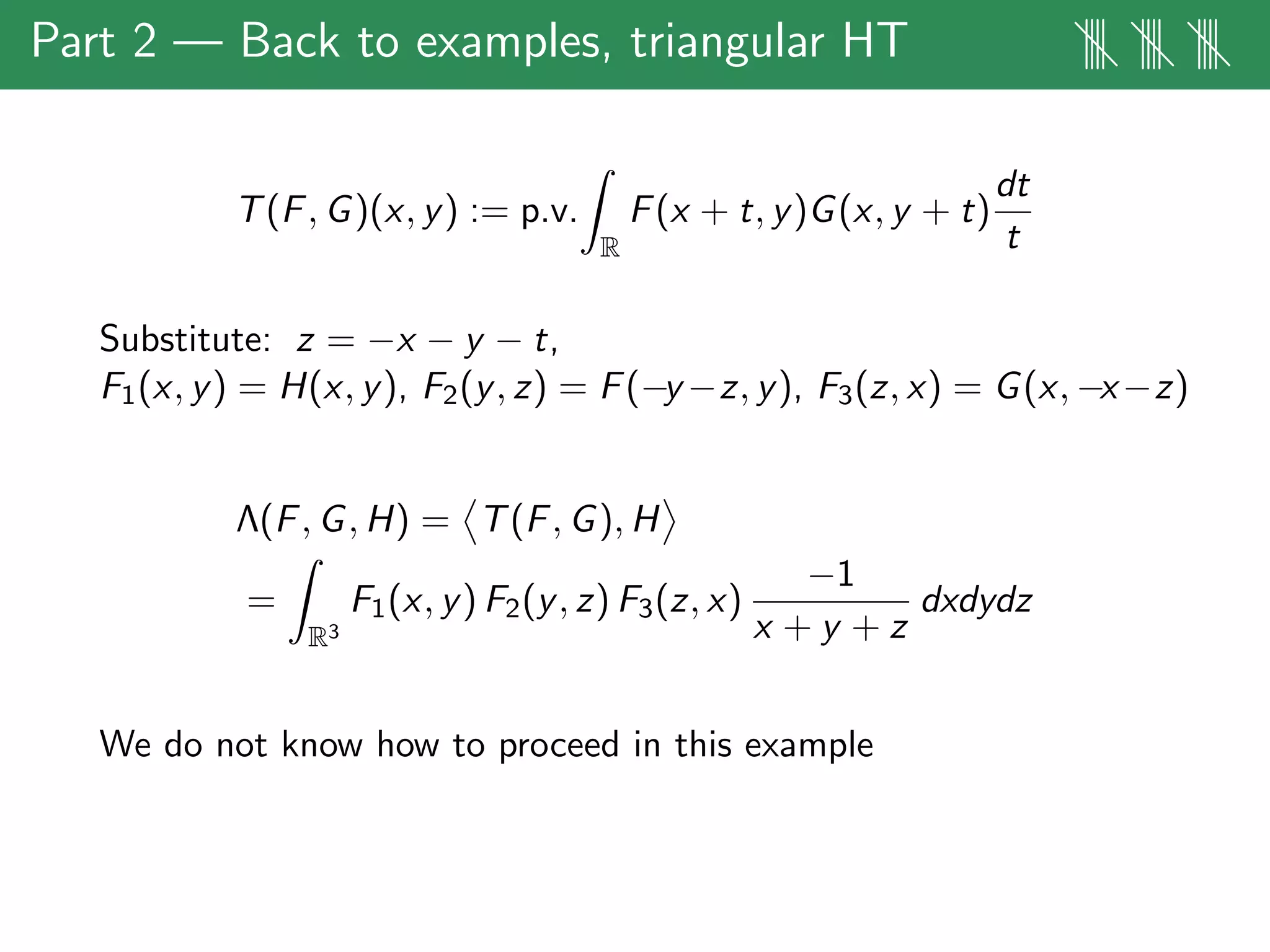

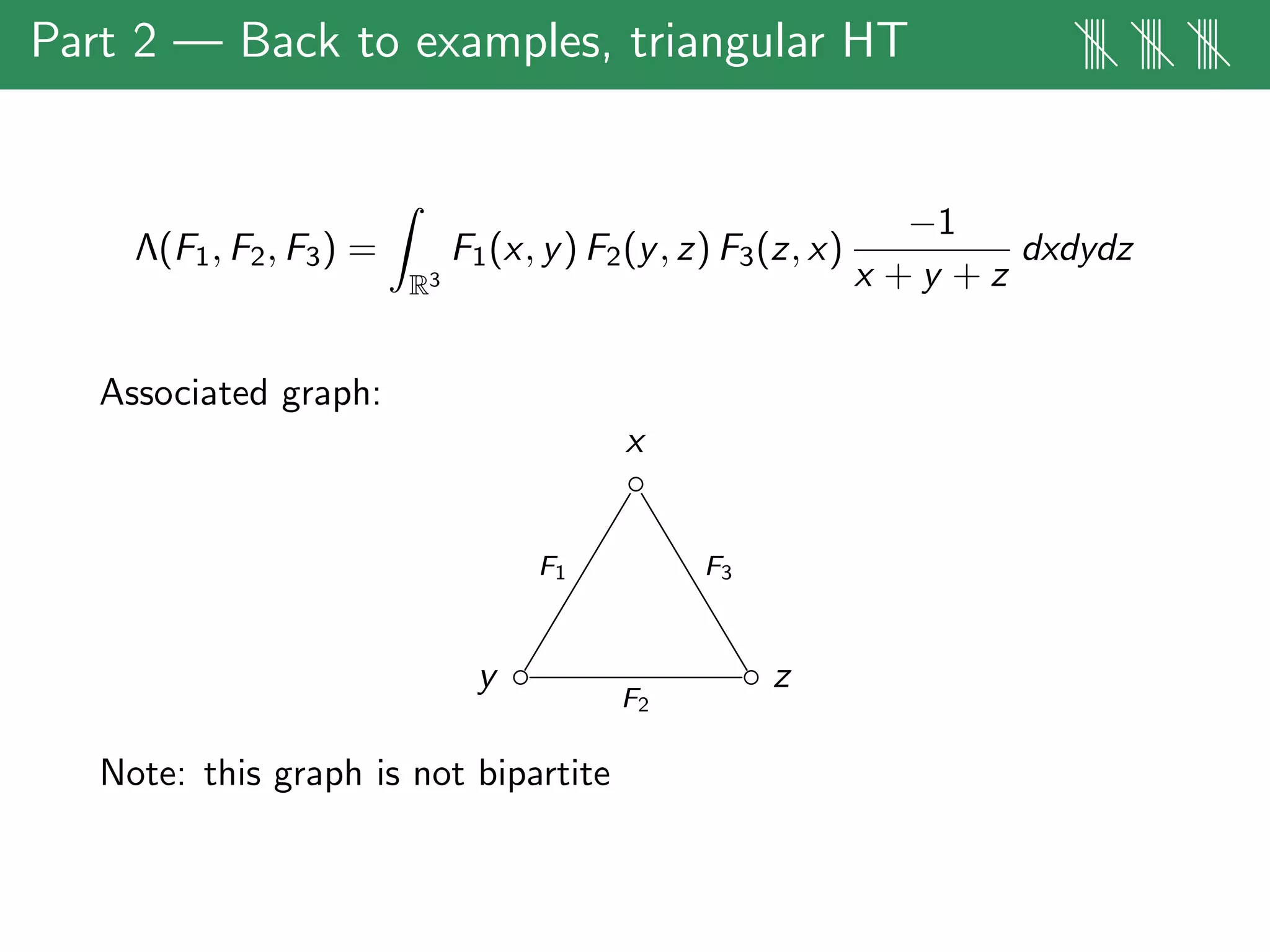

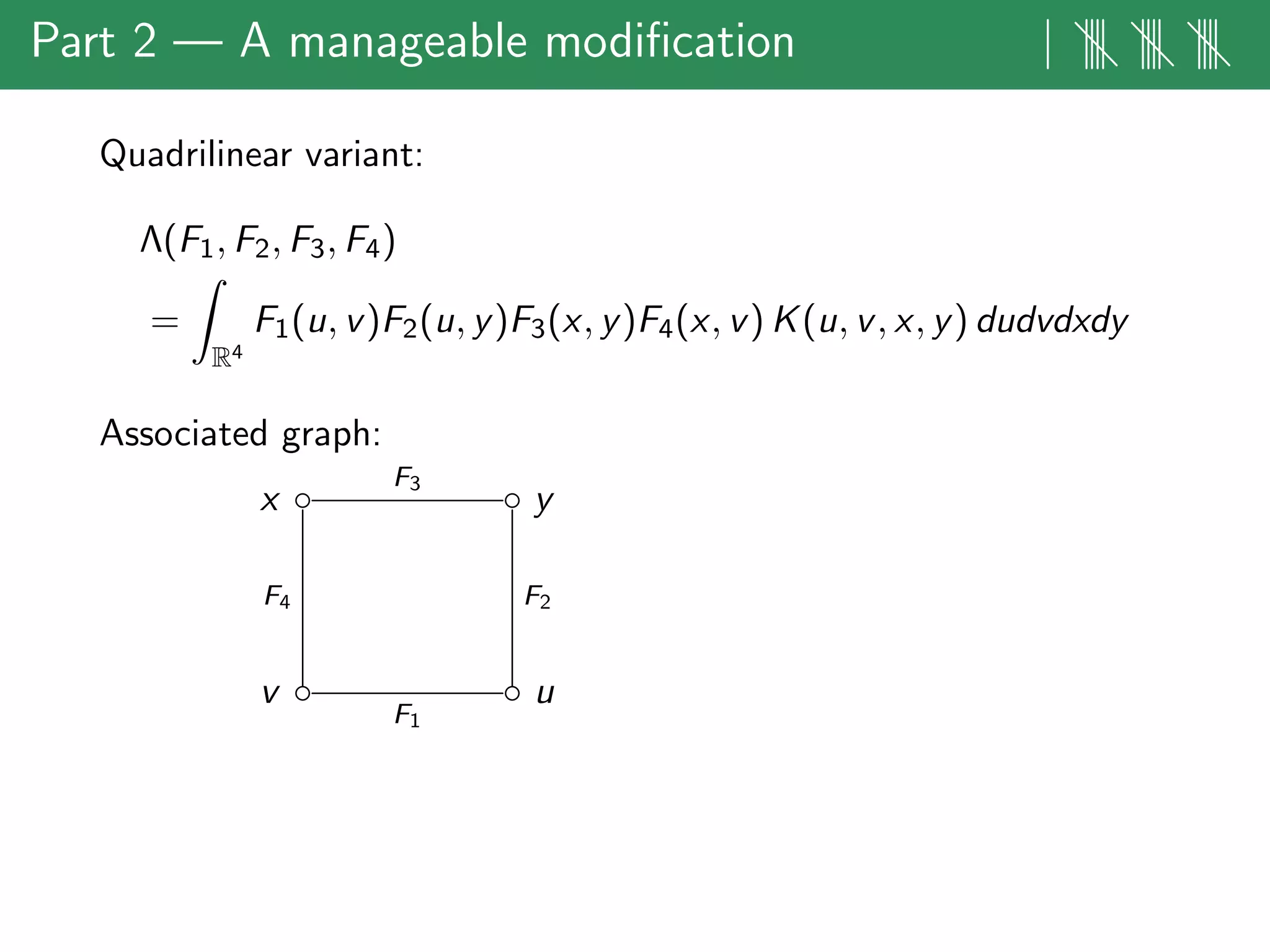

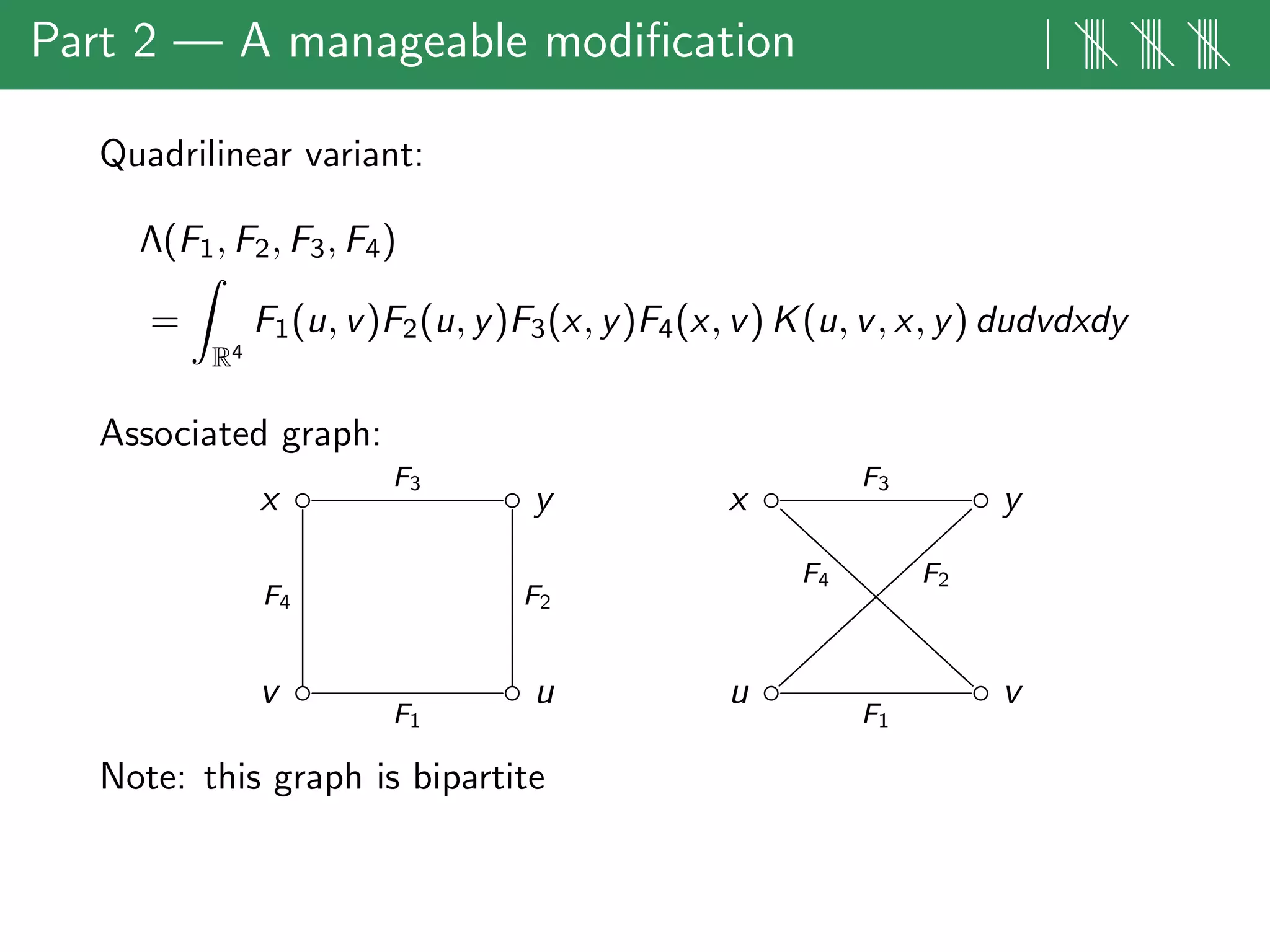

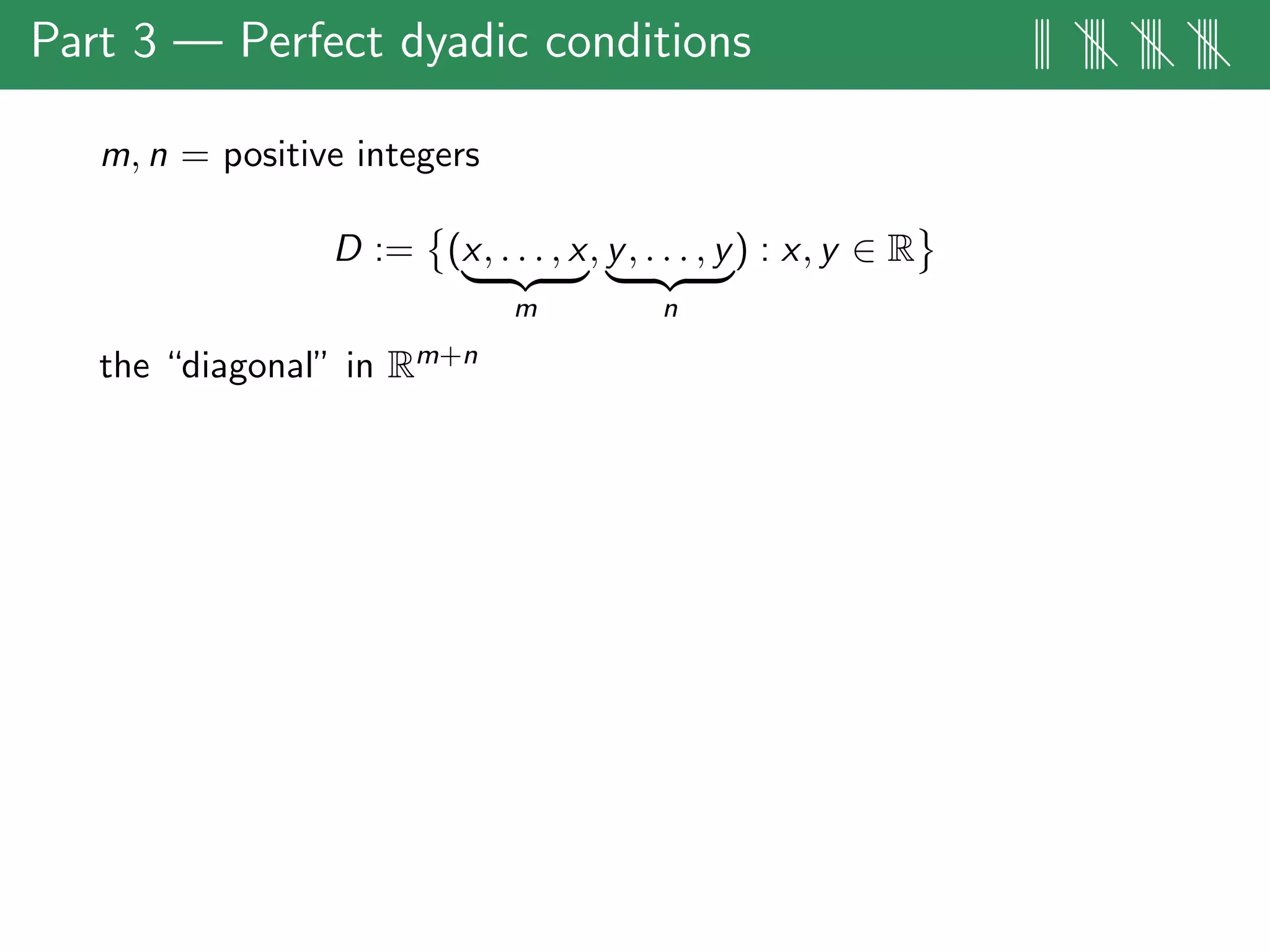

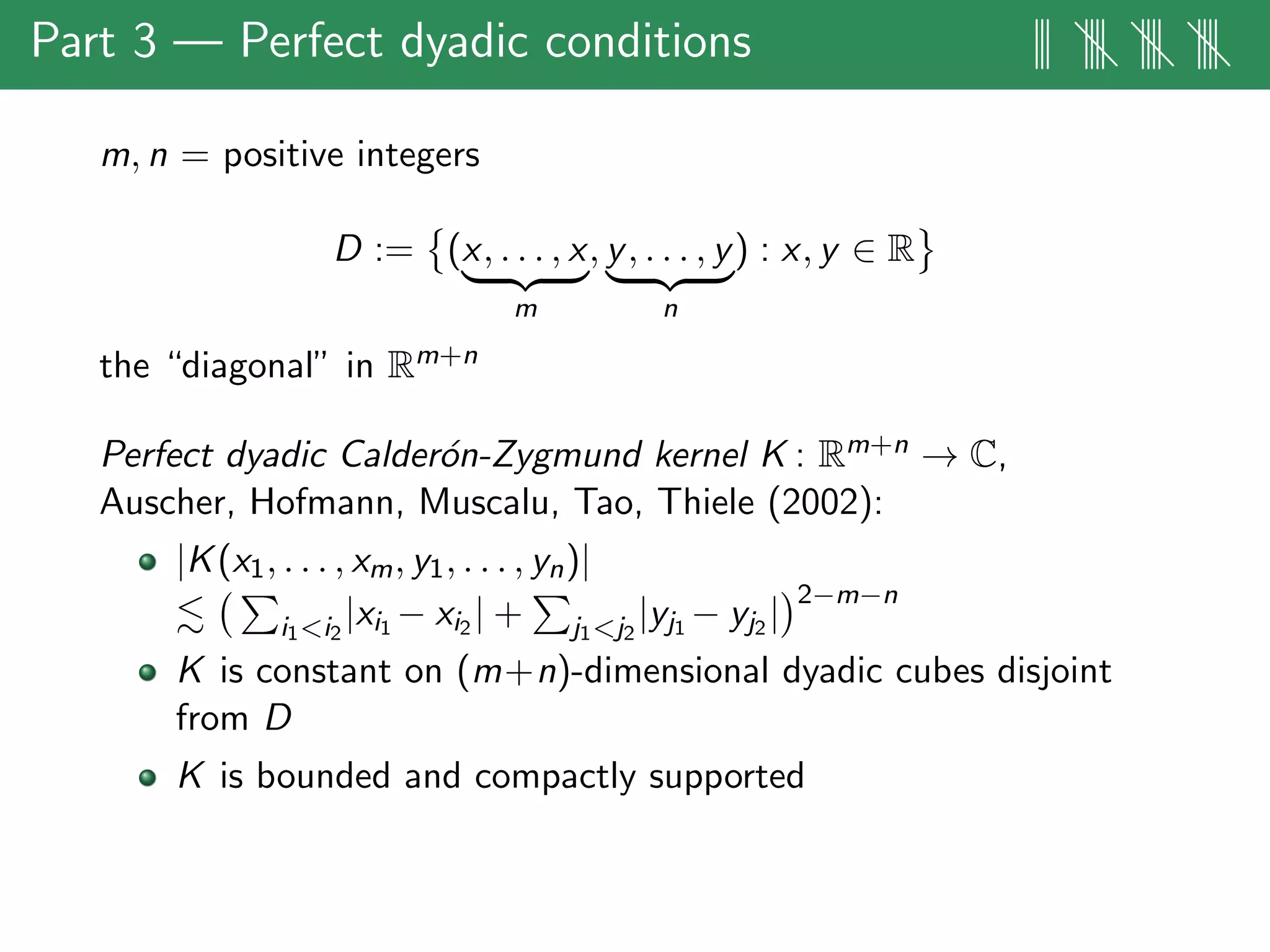

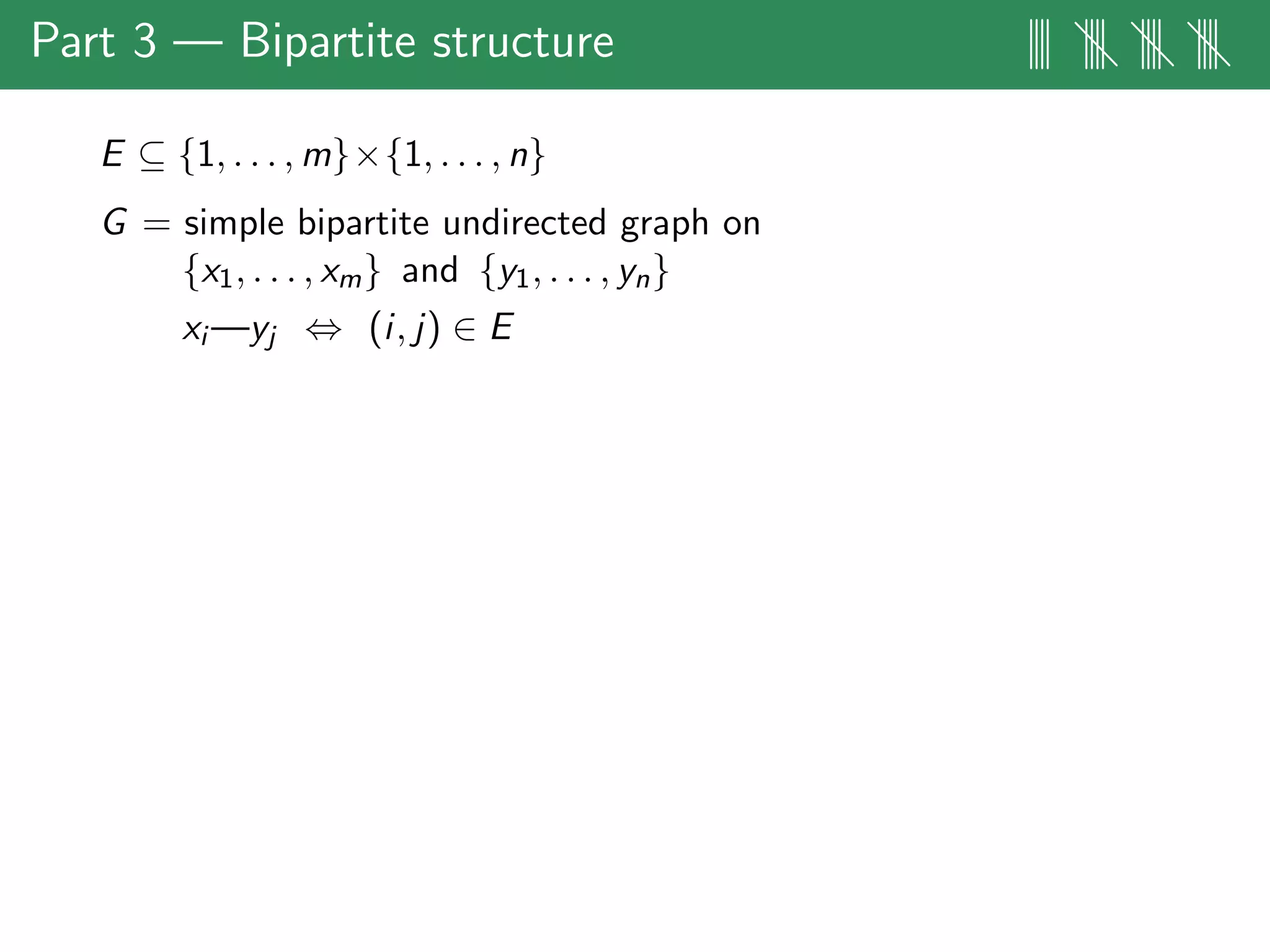

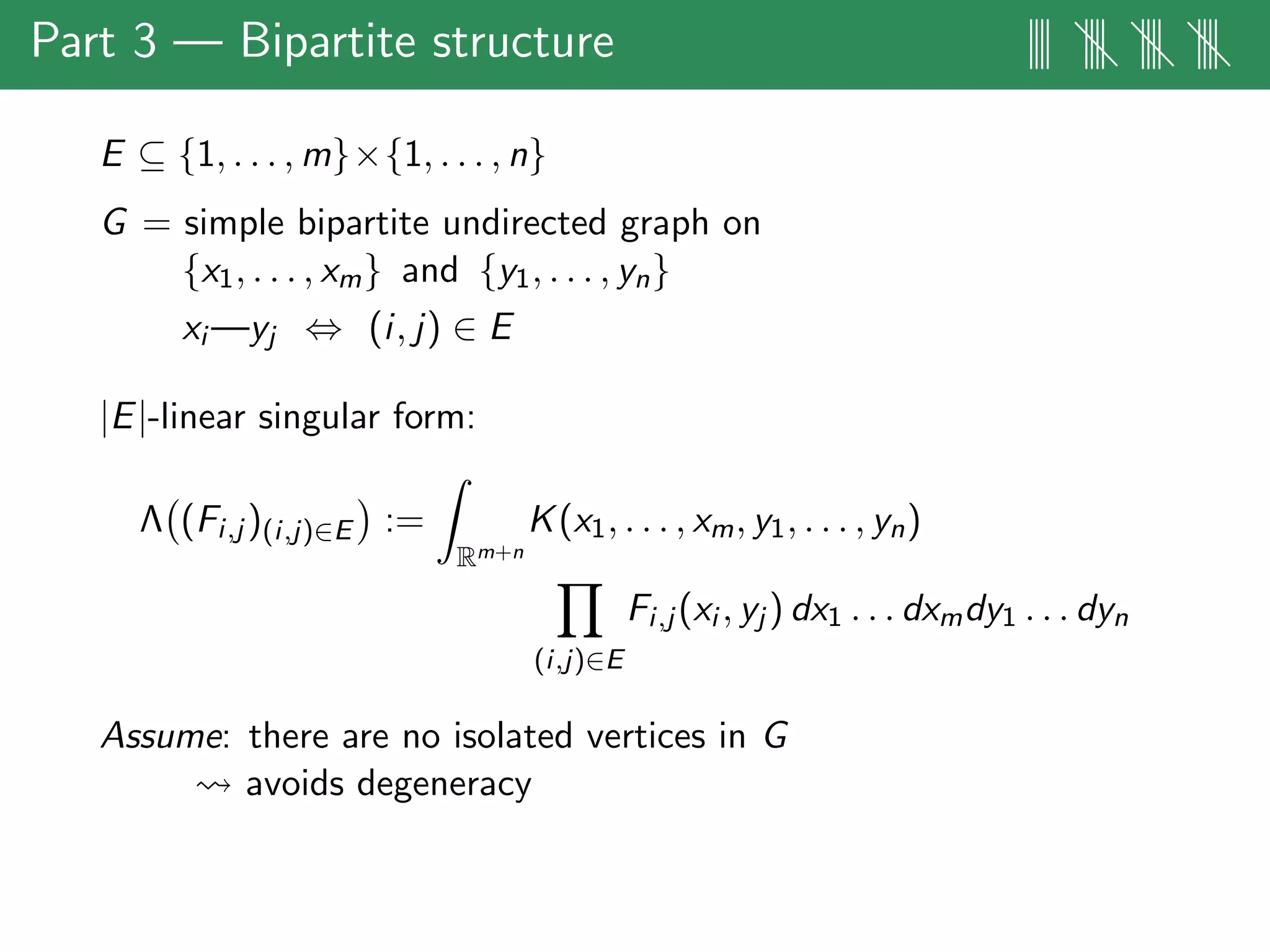

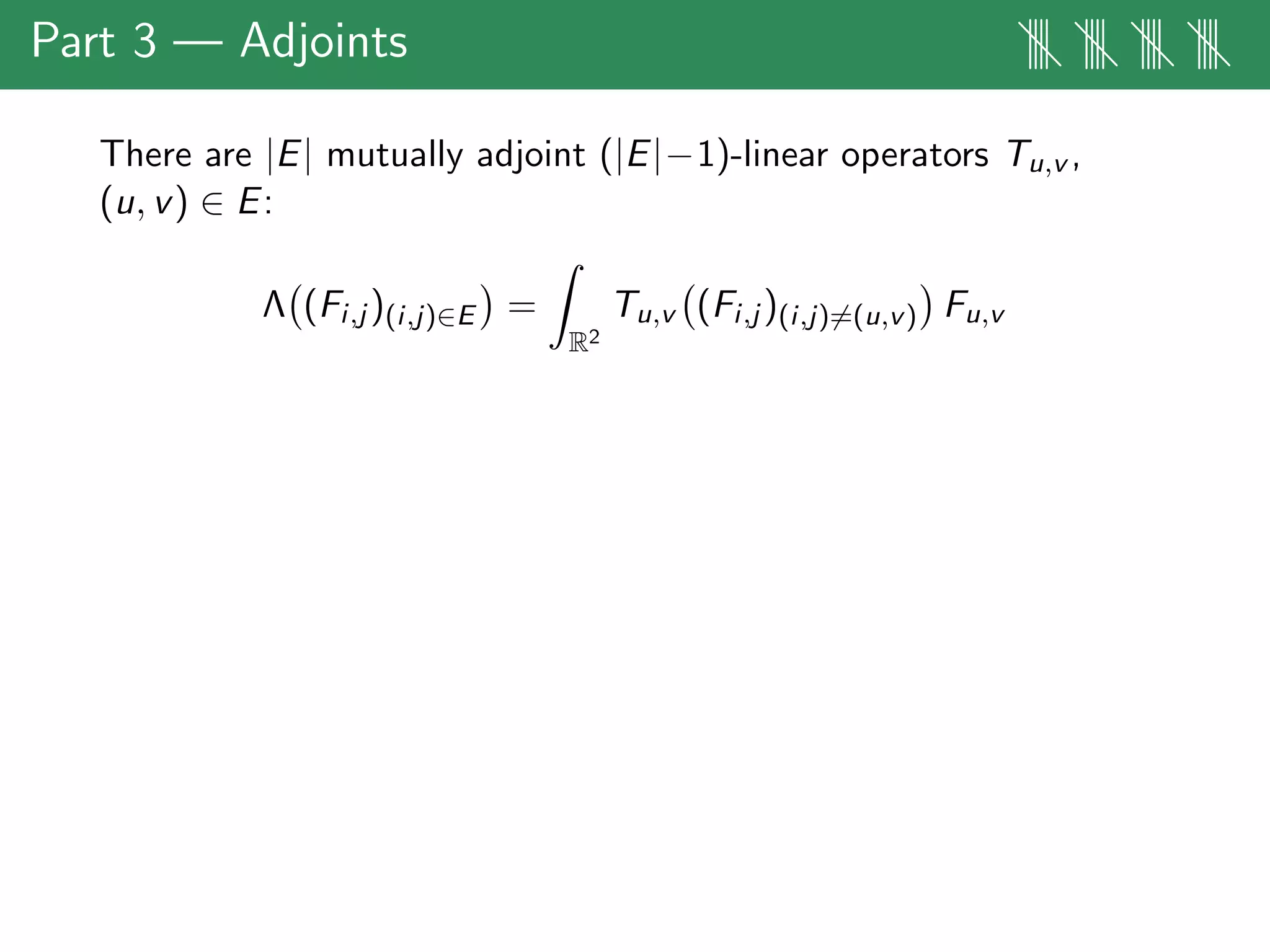

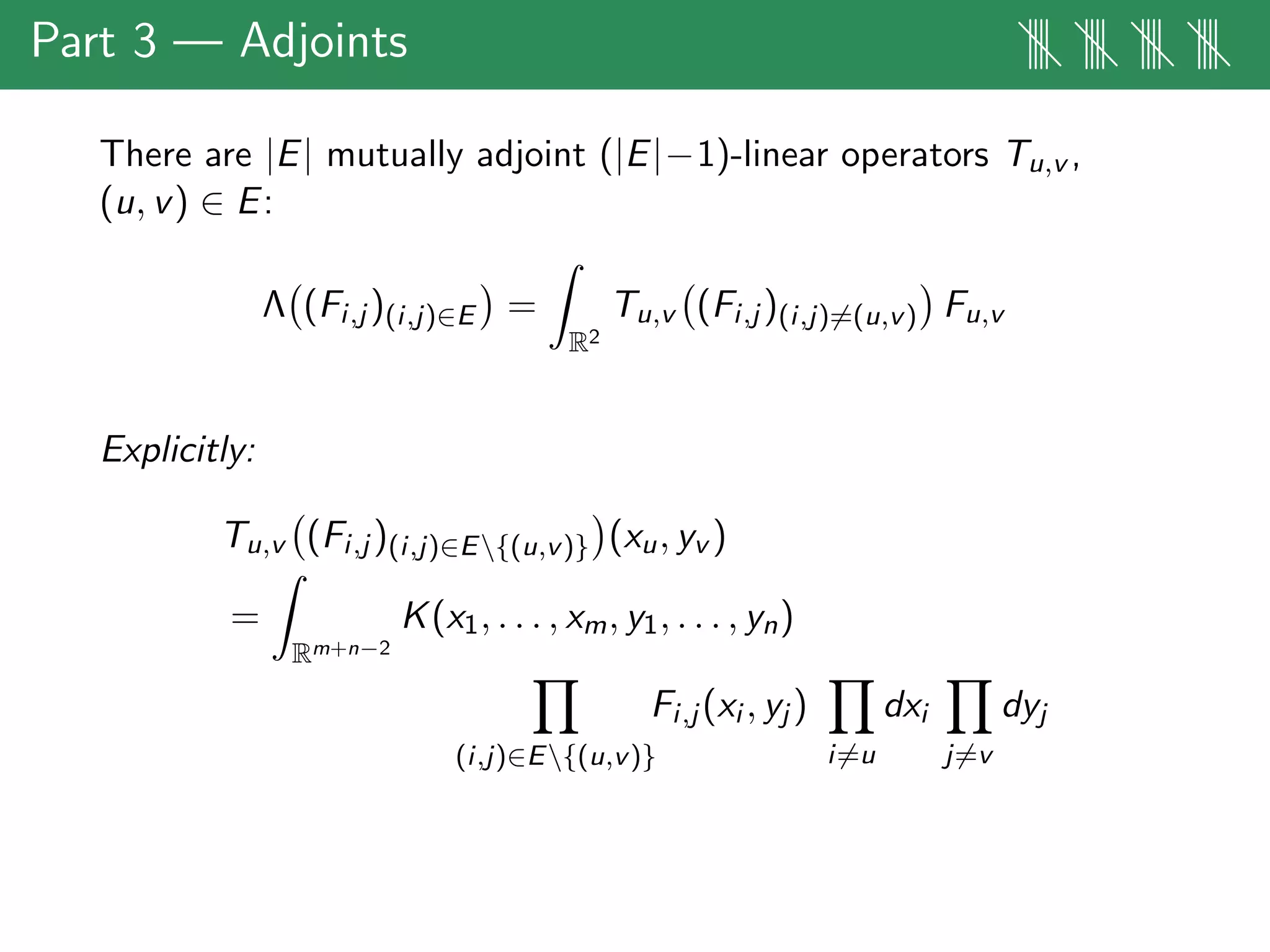

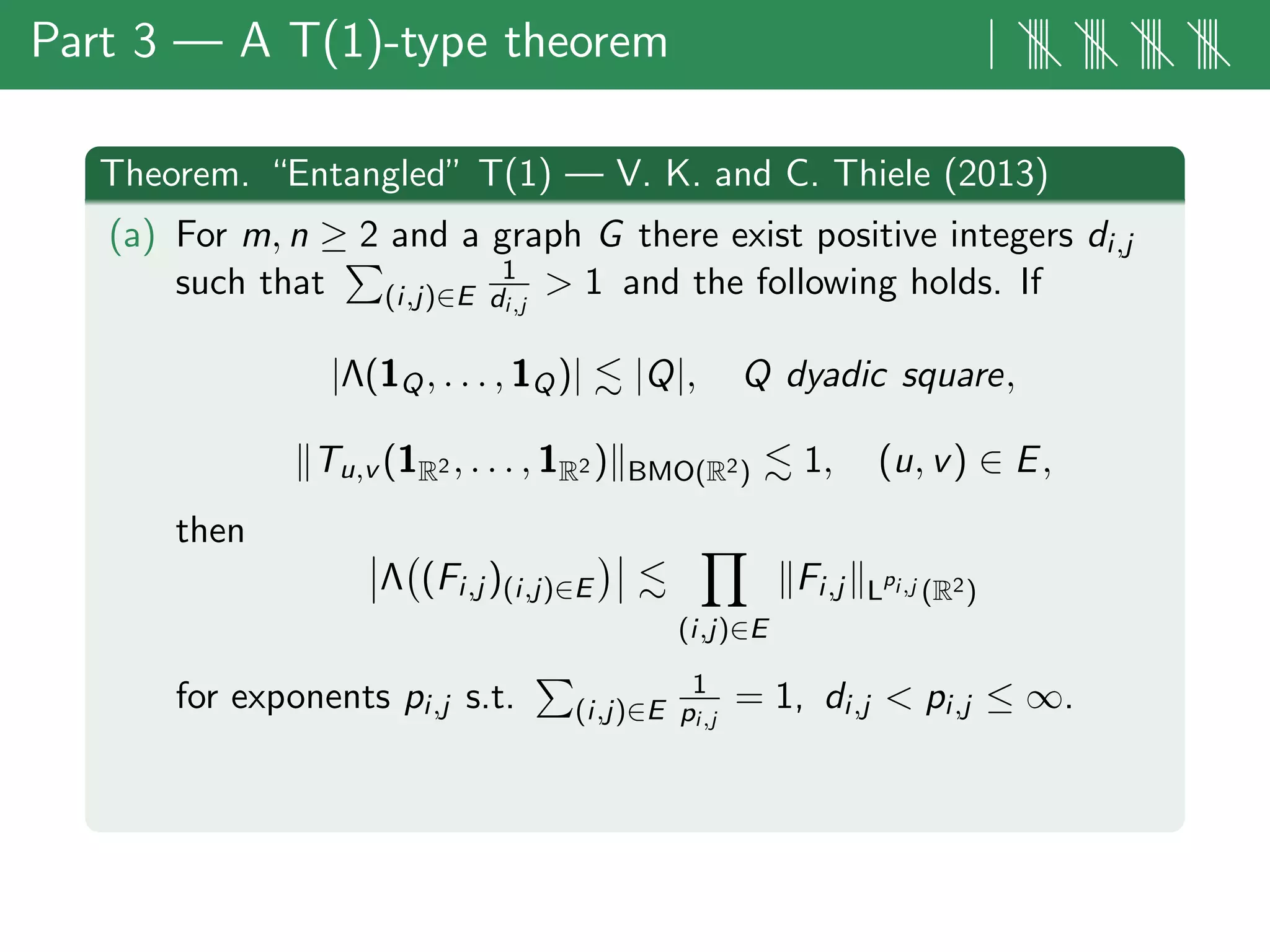

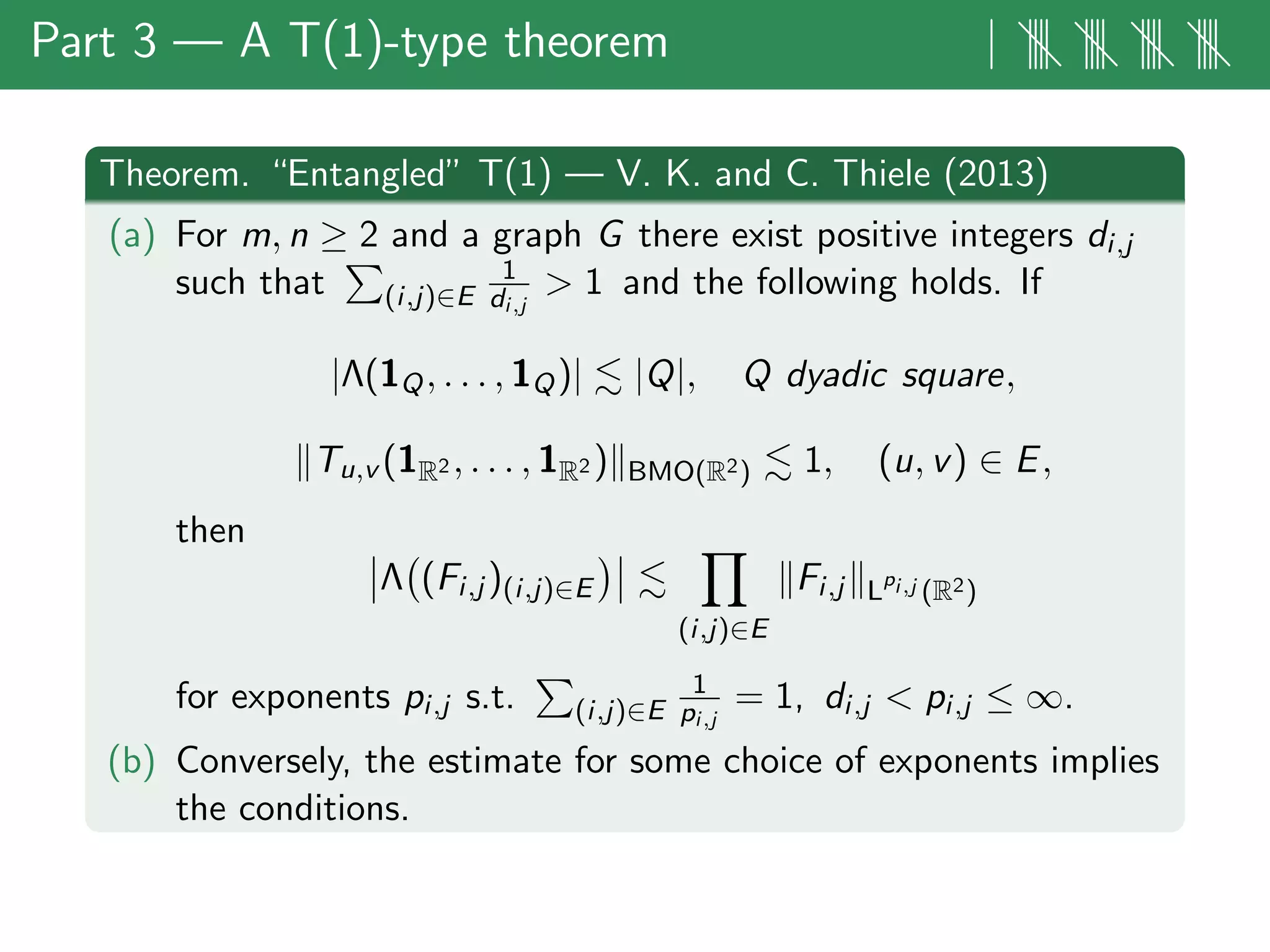

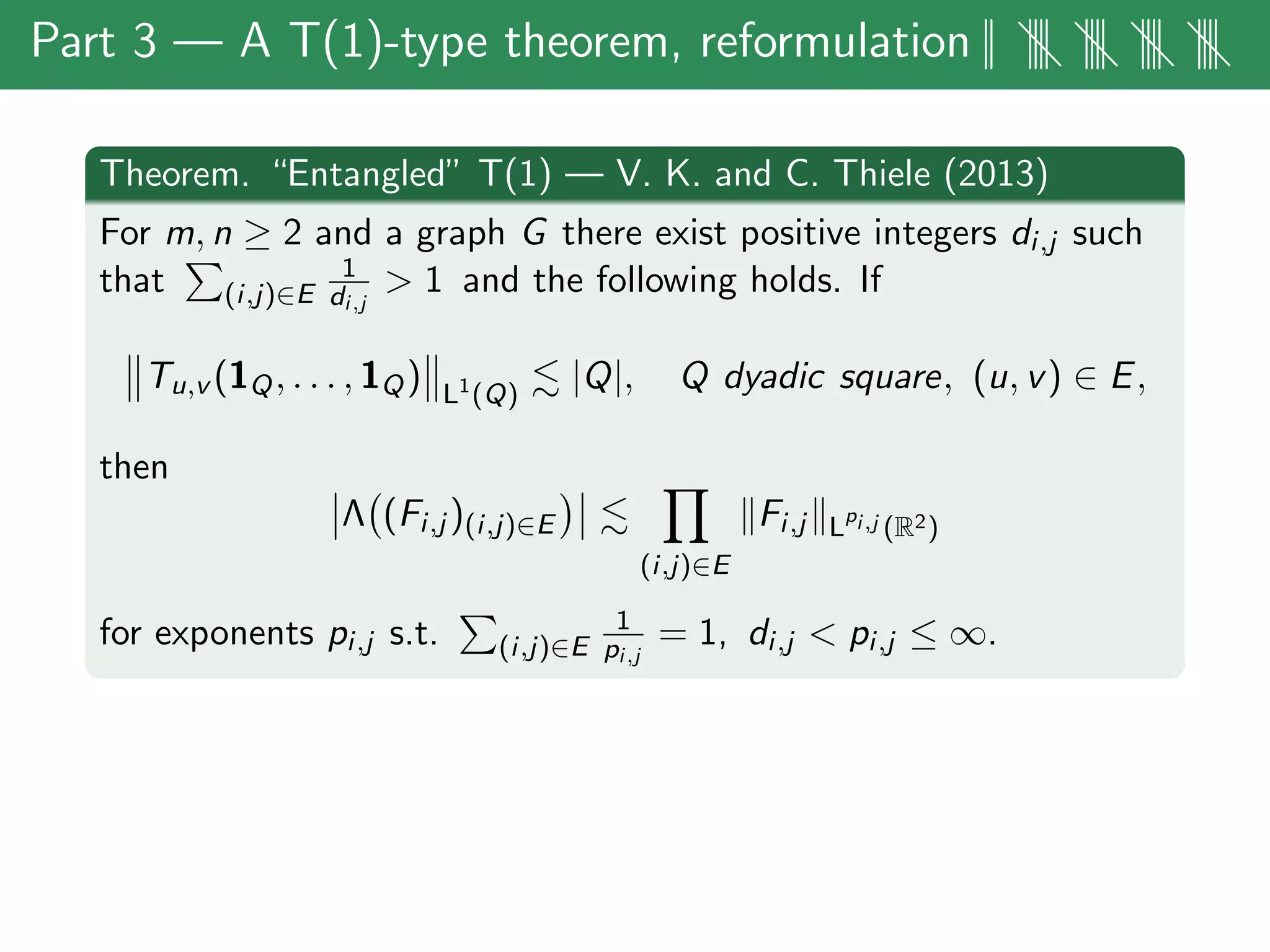

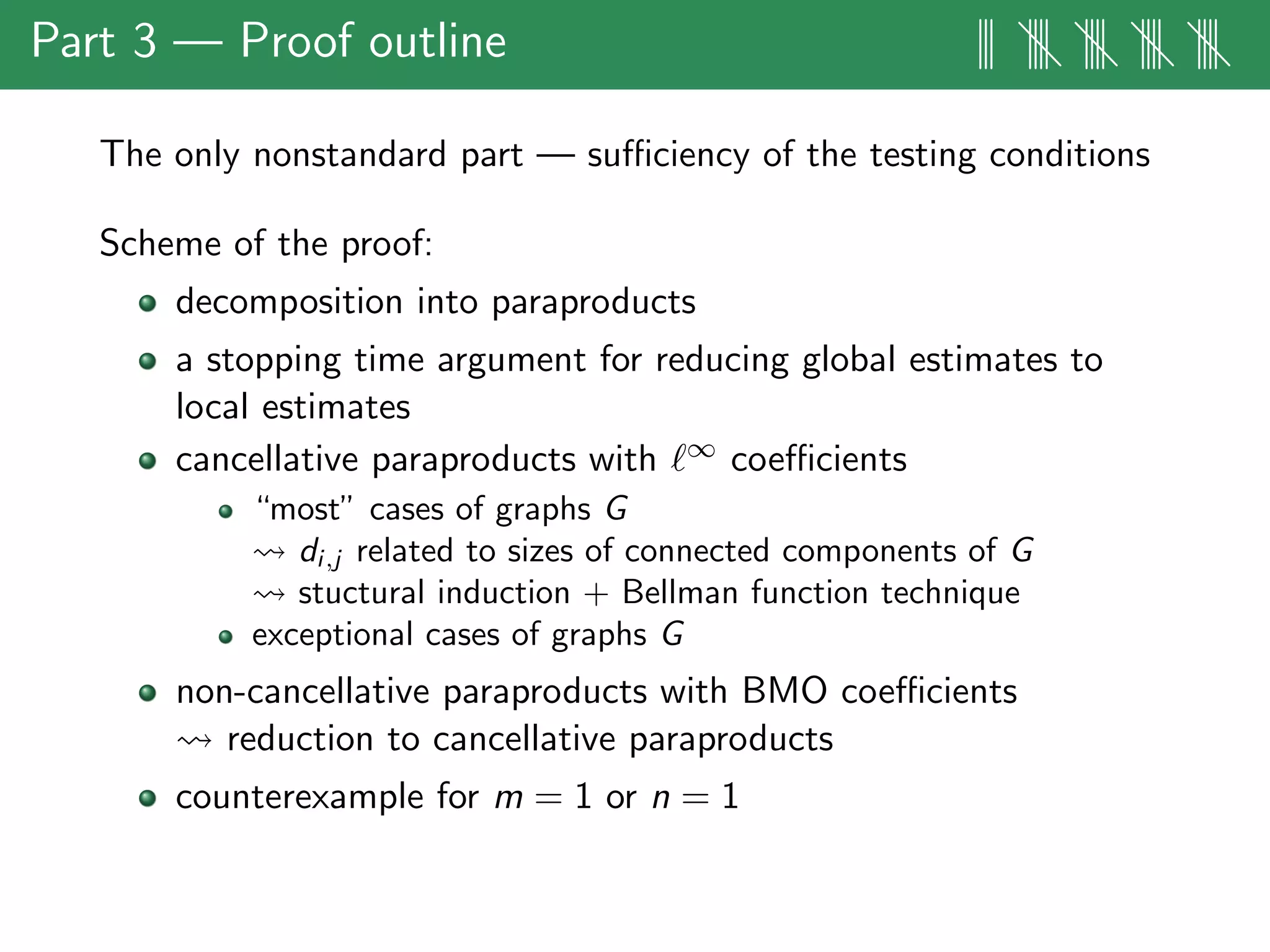

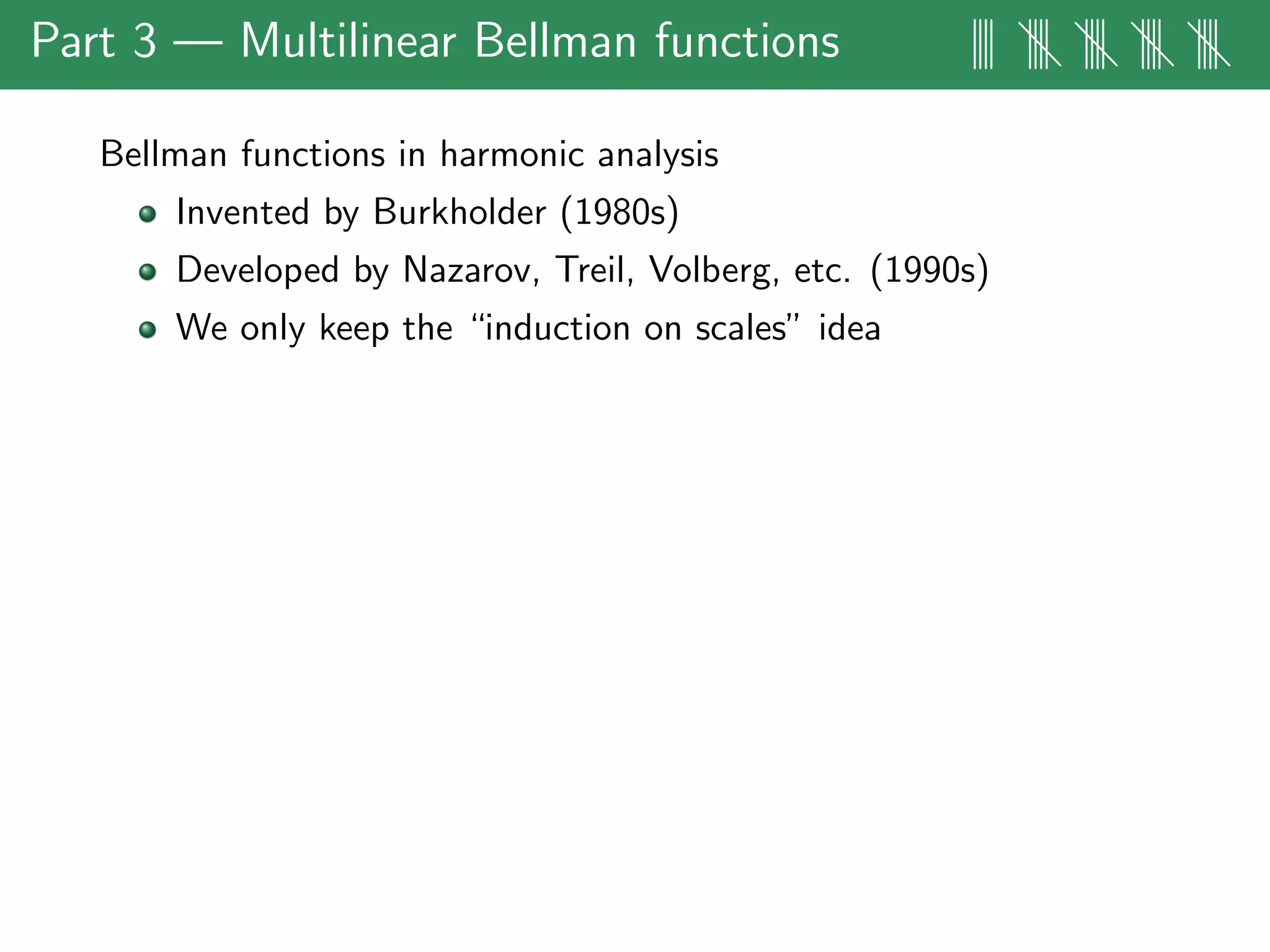

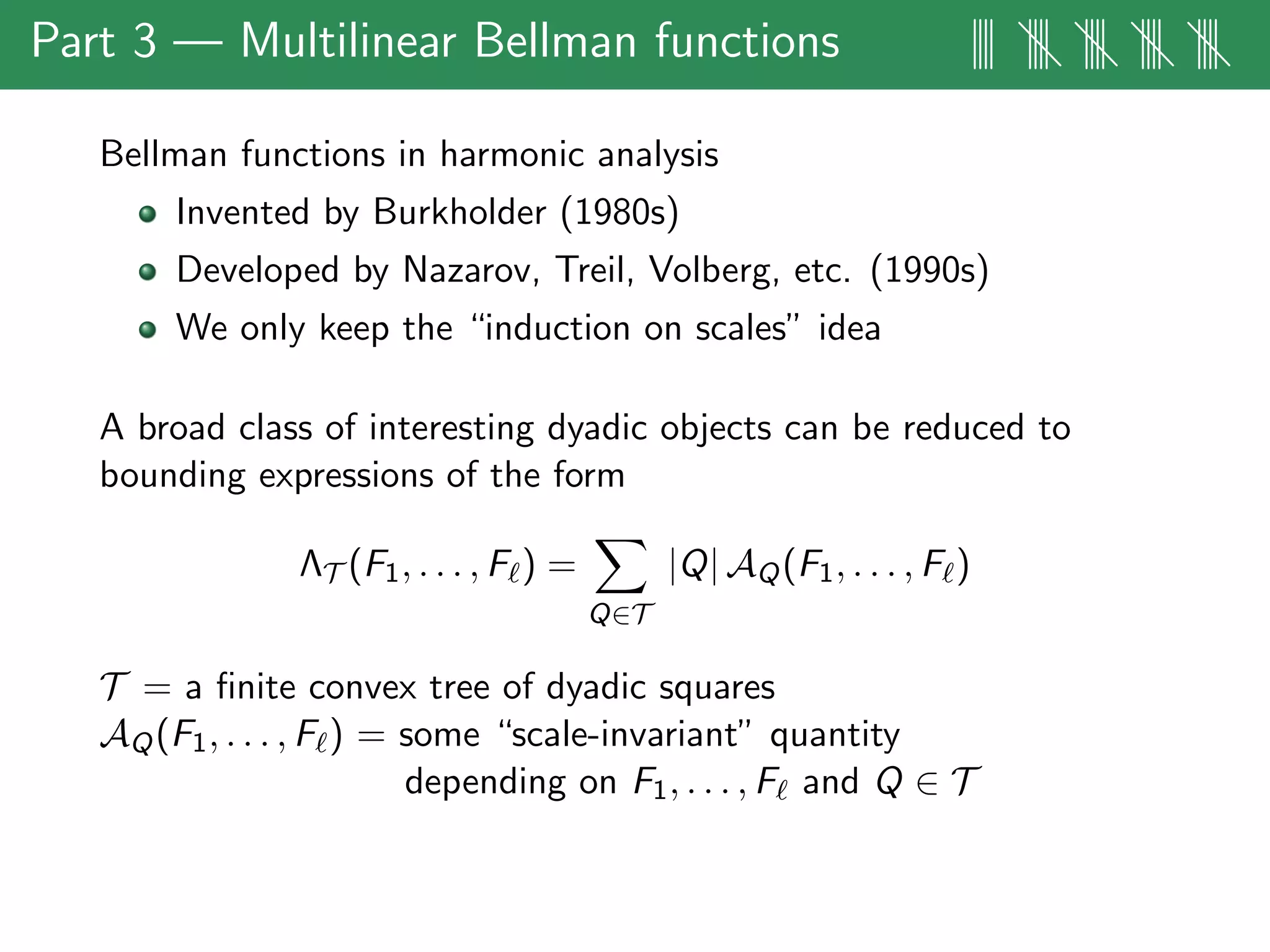

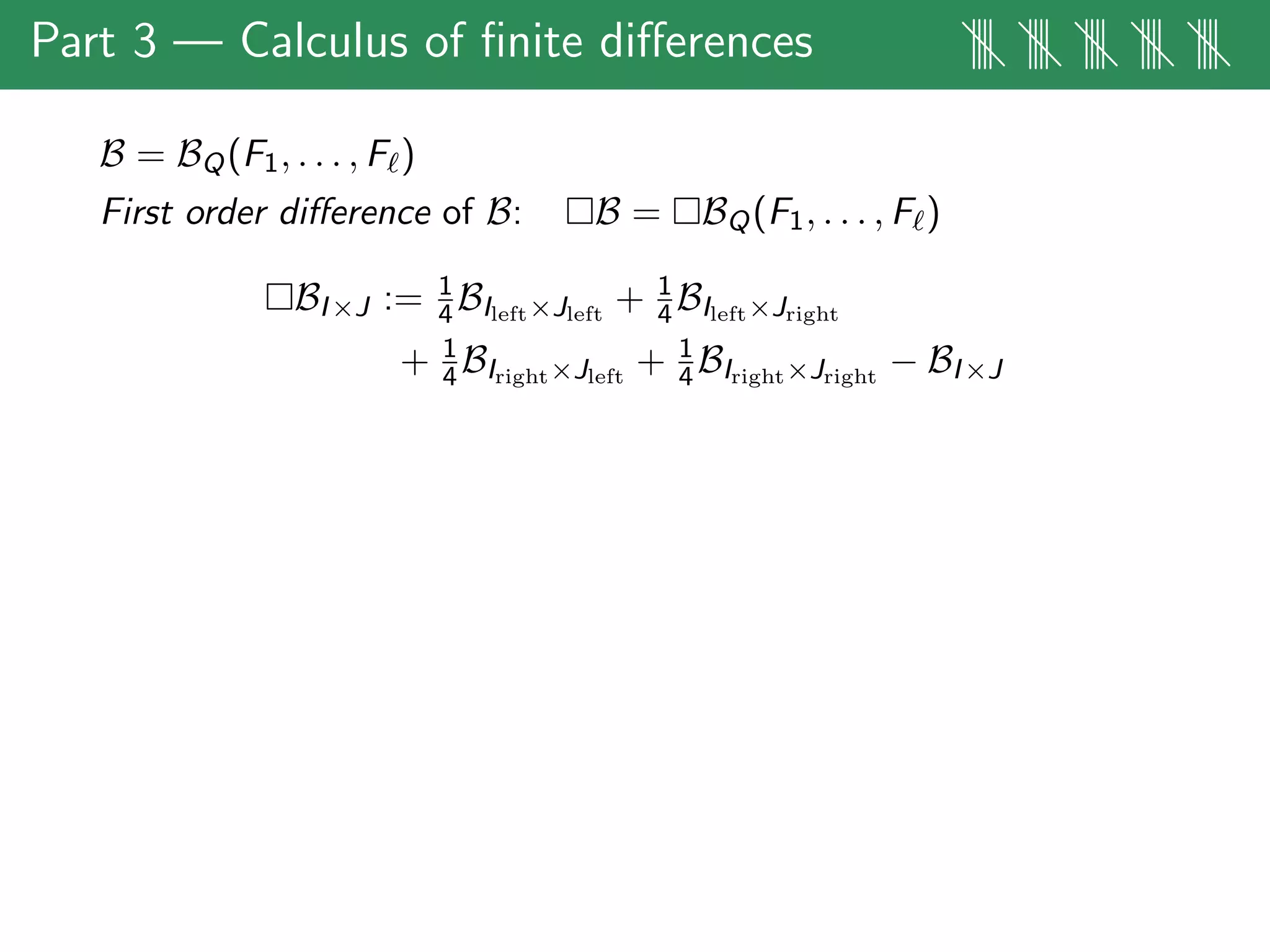

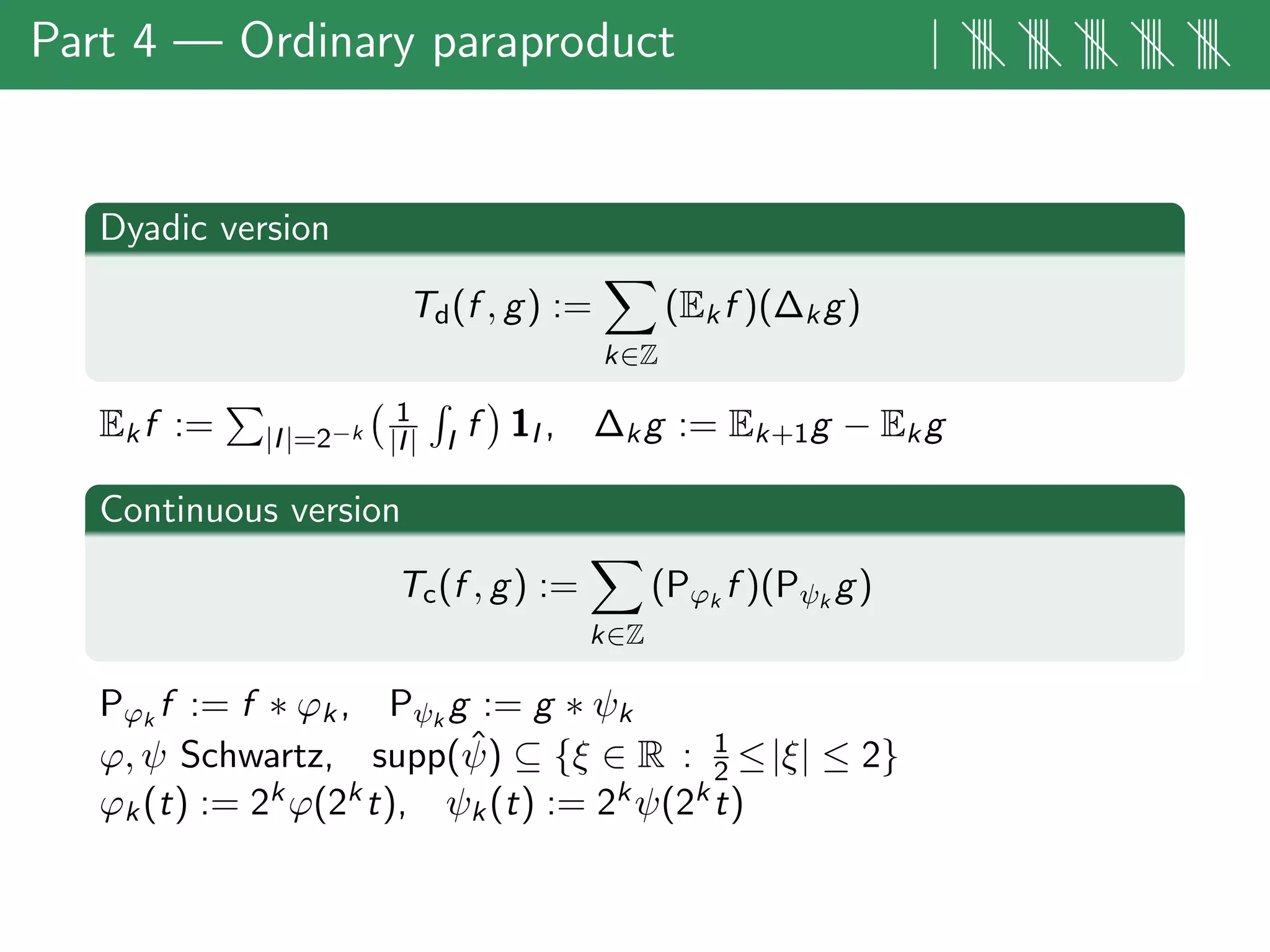

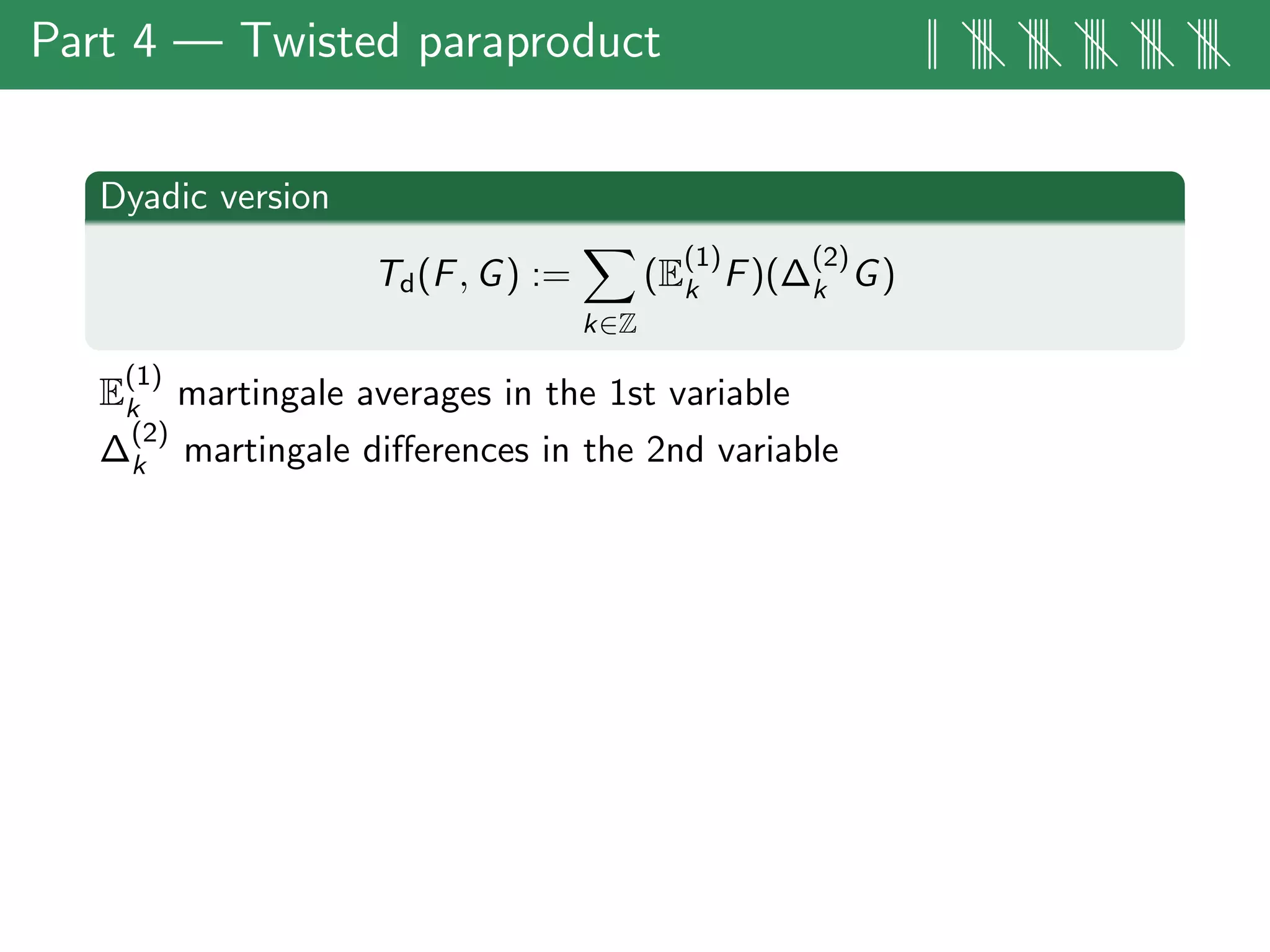

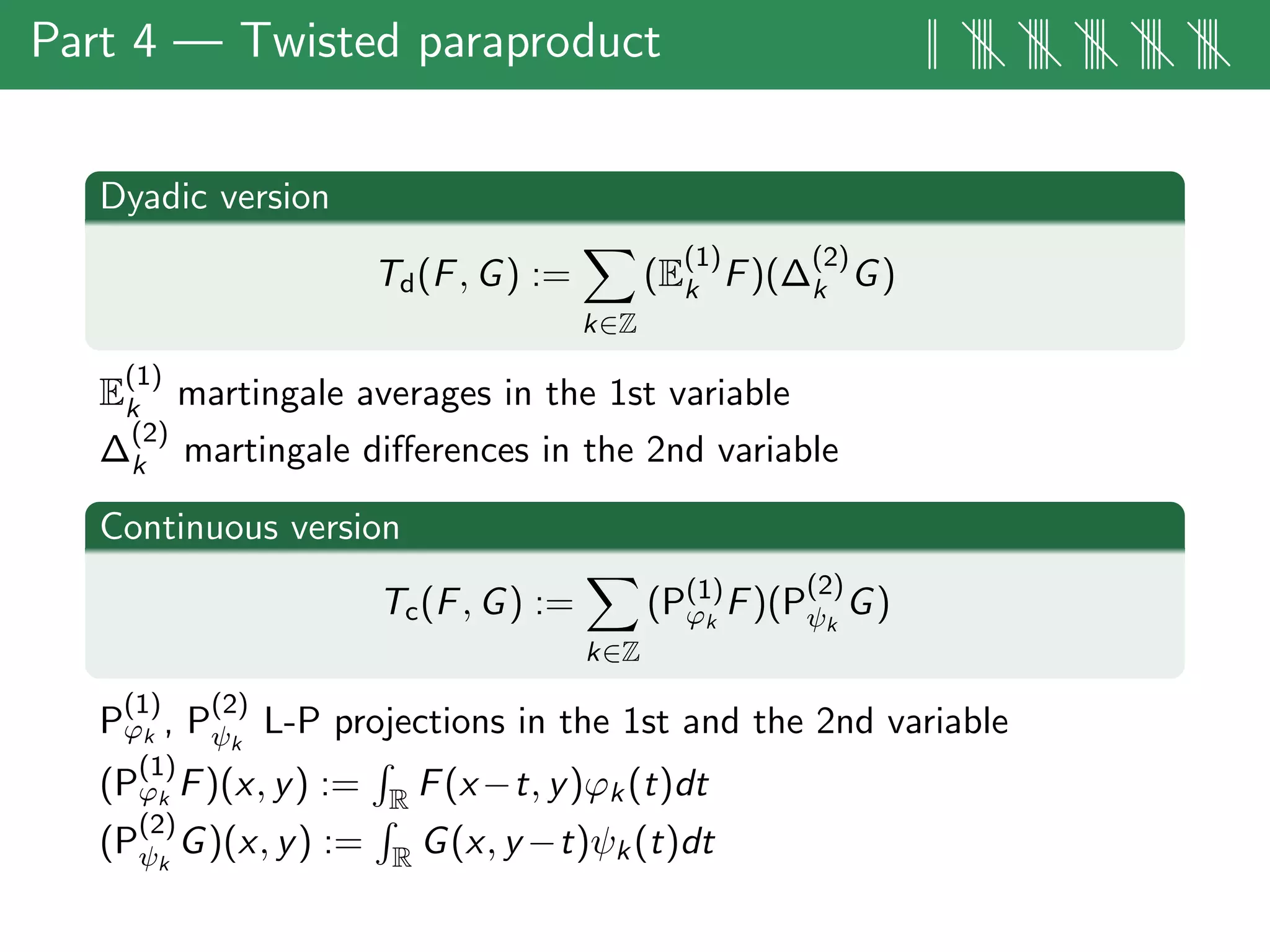

The document discusses estimates for non-standard bilinear multipliers, presenting various results and motivations for multilinear estimates and techniques. It covers the transition from dyadic model operators to continuous-type operators, as well as examples of bilinear and trilinear Hilbert transforms. The talk emphasizes open problems in the field and the complex structures involved in multilinear singular integral forms.

![Part 4 — Twisted paraproduct || |||| |||| |||| |||| ||||

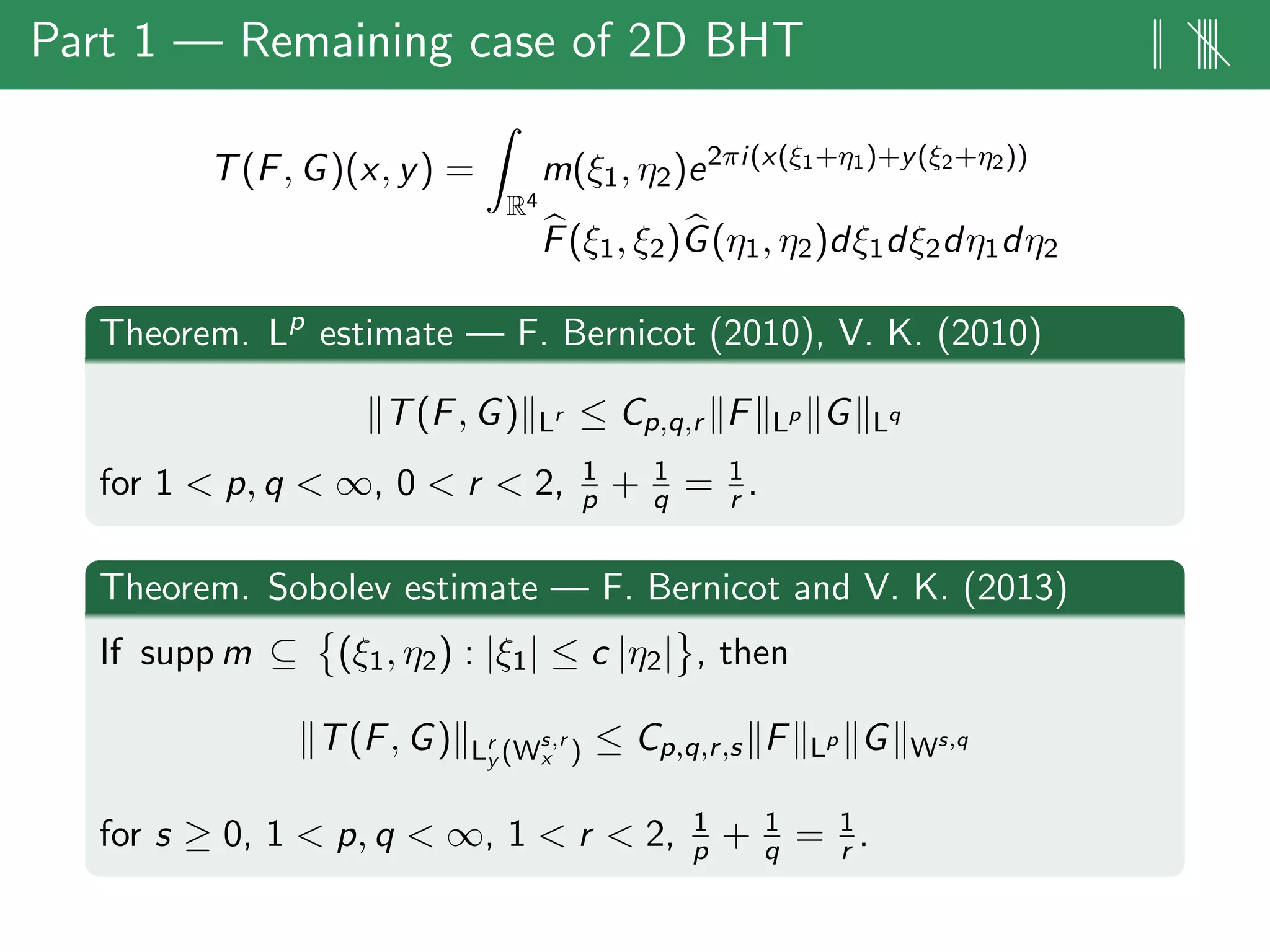

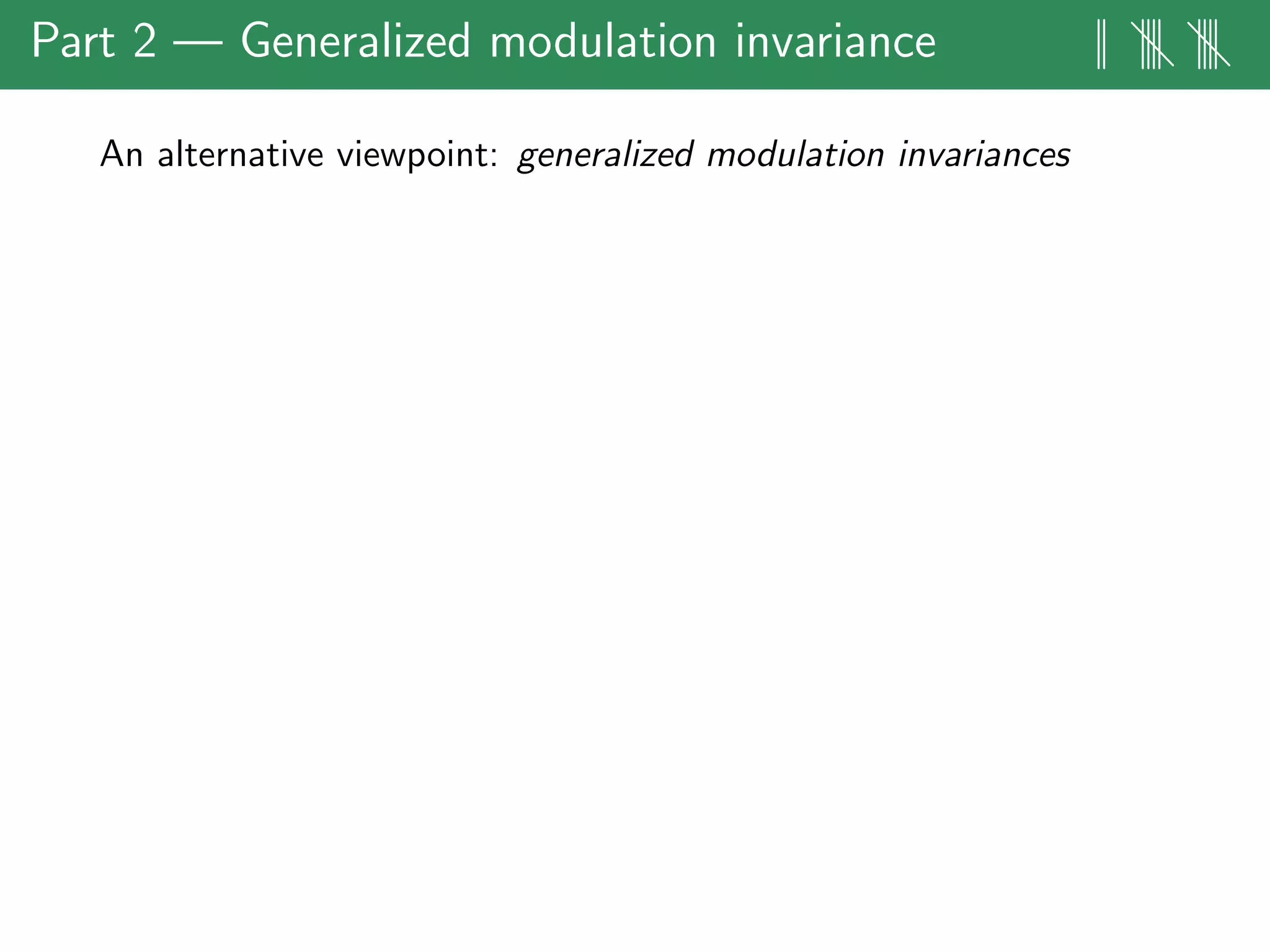

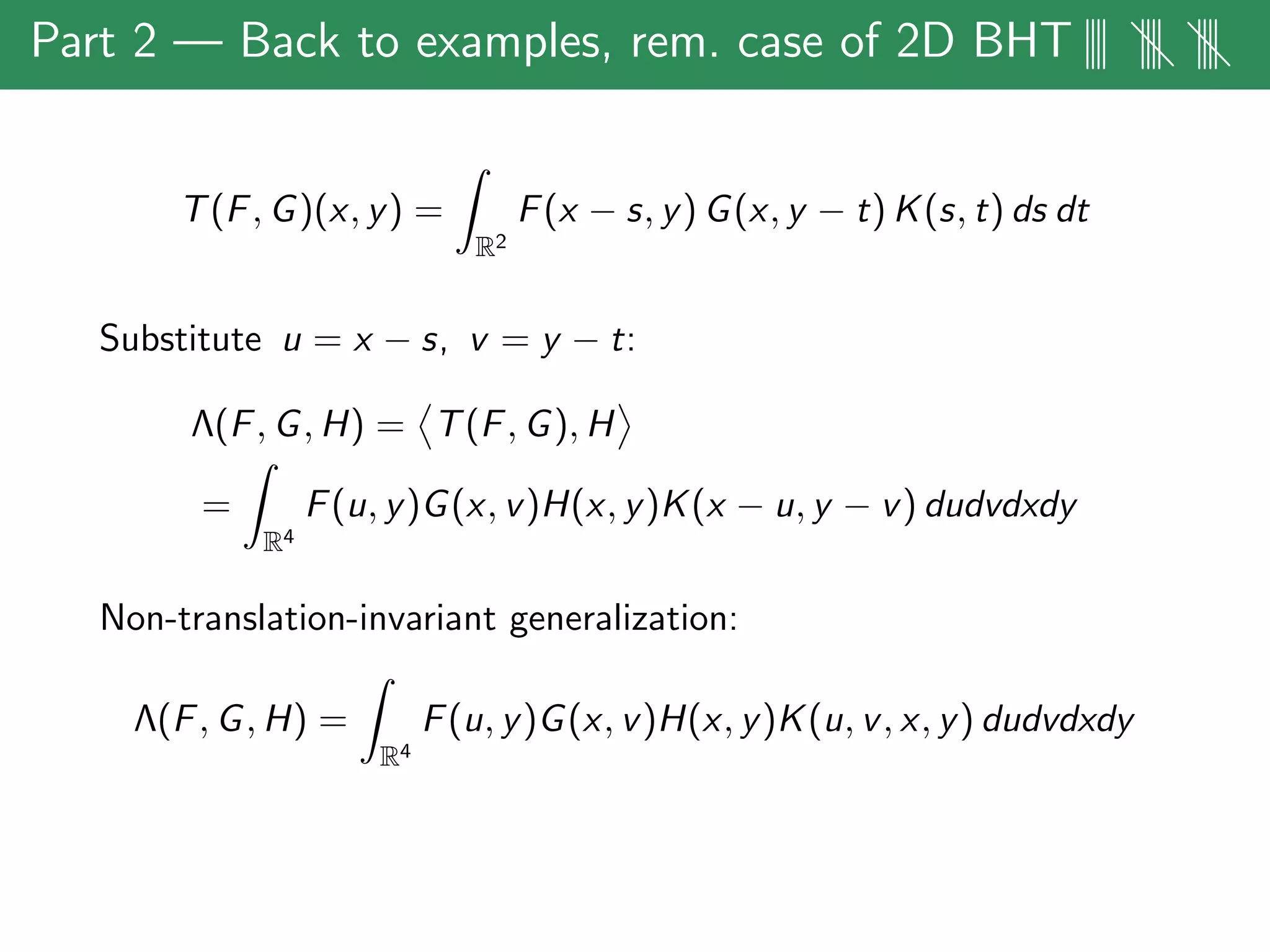

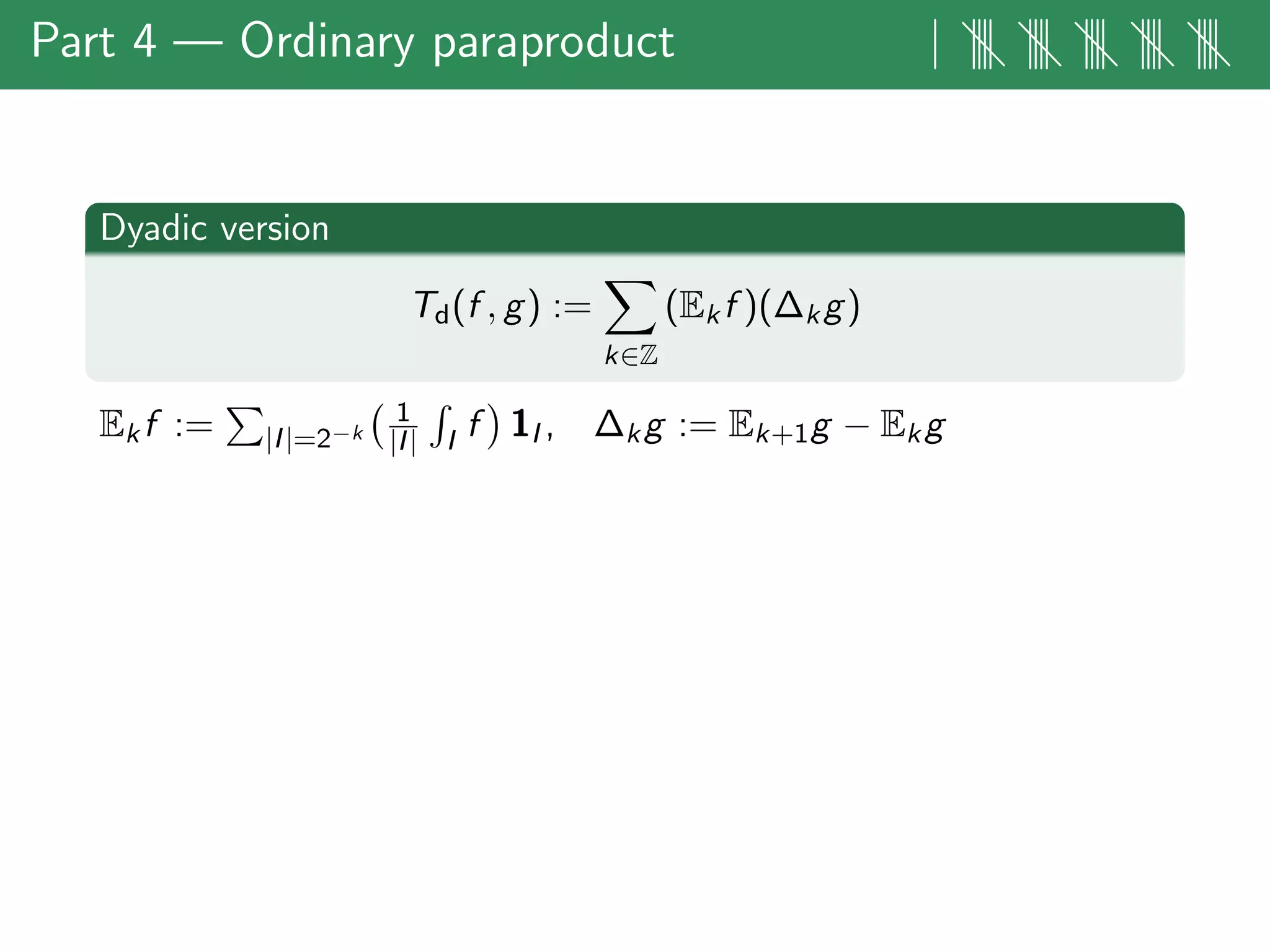

Dyadic version

Td(F, G) :=

k∈Z

(E

(1)

k F)(∆

(2)

k G)

Continuous version

Tc(F, G) :=

k∈Z

(P(1)

ϕk

F)(P

(2)

ψk

G)

Bilinear multipliers from our theorems reduce to these

using cone decomposition of the symbol:

m =

j

m[j]

from the Fourier series

m[j]

(ξ1, η2) =

k∈Z

ϕ

[j]

k (ξ1) ψ

[j]

k (η2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kovaccrm2013-190108093130/75/Estimates-for-a-class-of-non-standard-bilinear-multipliers-84-2048.jpg)