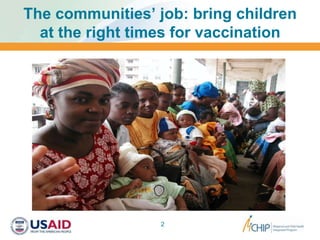

1) The document discusses a project in Timor-Leste that partnered with communities to improve vaccination rates by sharing responsibility between health services and communities.

2) Key activities of the project included community participation in micro-planning, training leaders, school orientations on immunization, and tracking children's vaccination status.

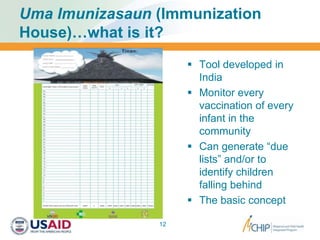

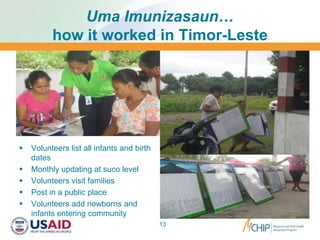

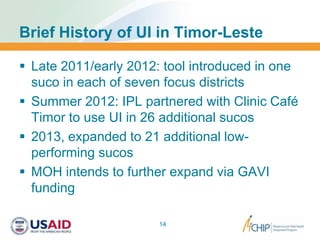

3) The "Uma Imunizasaun" tool, adapted from India, was used to monitor every child's vaccinations at the community level through volunteer record keeping and home visits to increase vaccination timeliness and coverage.