The document discusses chemical kinetics, which examines the rates of chemical reactions and how they are influenced by conditions like concentration, temperature, and catalysts. It defines key terms like the rate of reaction, average rate, and instantaneous rate. The rate of reaction depends on factors like the concentrations of reactants, temperature, phase, and presence of catalysts or inhibitors. Reaction rate laws relate the reaction rate to concentrations and determine the order of reactions. Differential and integrated rate equations are also discussed.

![1/21

Chemical Kinetics-complete note

energy-gateway.blogspot.com/2021/04/chemical-kinetics-complete-note.html

What is Chemical Kinetics?

Chemical kinetics also called reaction kinetics helps us understand the rates of reactions and how it is influenced by certain conditions. It

further helps to gather and analyze the information about the mechanism of the reaction and define the characteristics of a chemical

reaction.

Read more: Chemical Kinetics

What is Rate of Reaction(ROR)?

The rate of reaction or reaction rate is the speed at which reactants are converted into products.

Rate of Reaction Formula

Let’s take a traditional chemical reaction.

a A + b B → p P + q Q

Capital letters (A&B) denote reactants and the (P&Q) denote products, while small letters (a,b,p,q) denote Stoichiometric coefficients.

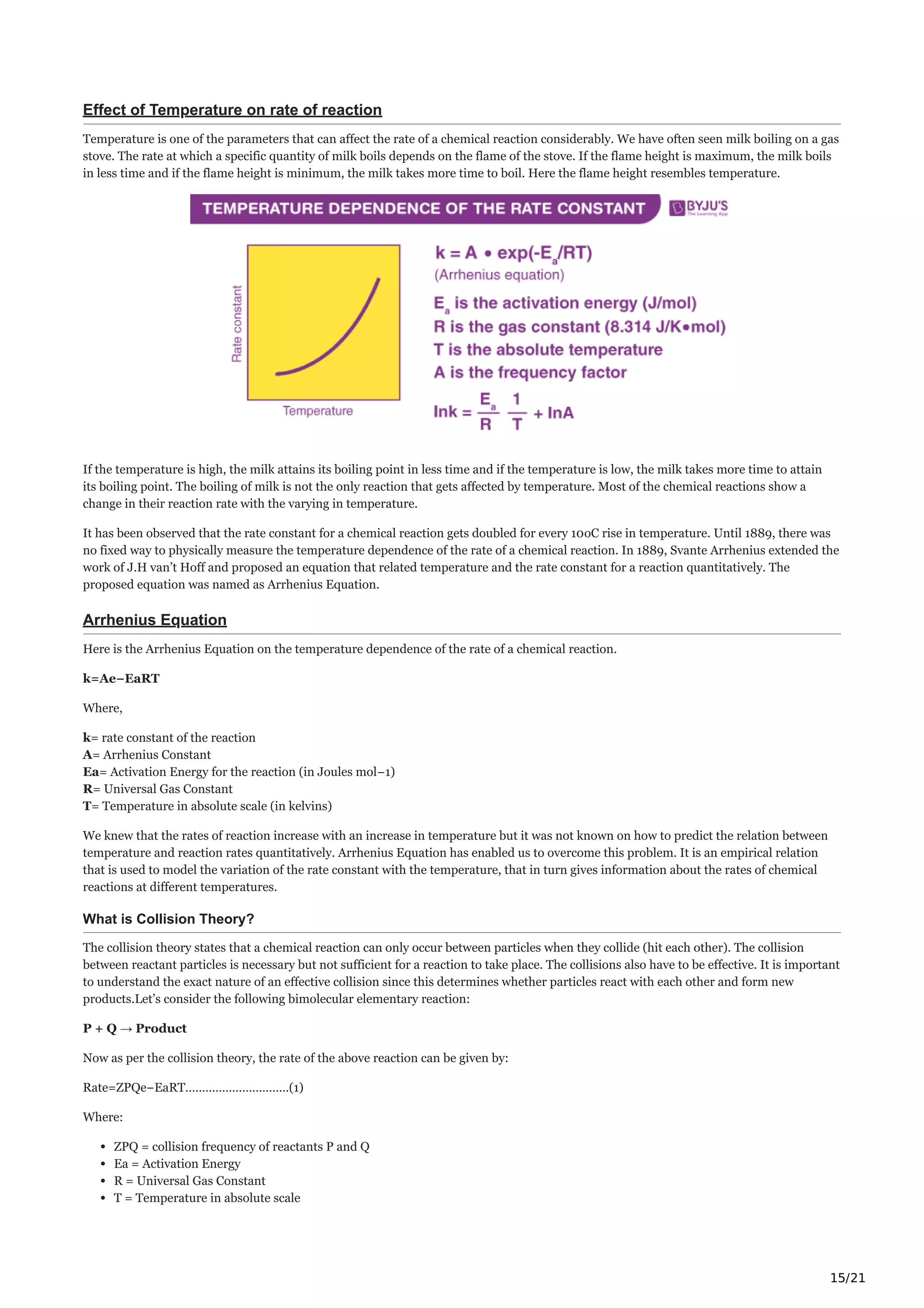

As per IUPAC’s Gold Book, the rate of reaction r occurring in a closed system without the formation of reaction intermediates under

isochoric conditions is defined as:

Here, the negative sign is used to indicate the decreasing concentration of the reactant.

Average Rate of reaction

Now let us consider the following reaction to understand even more clearly.

A → B

In this reaction a reactant A undergoes a chemical reaction to give a product B. It is a general convention to represent the concentration of

any reactant or product as [reactant] or [product]. So the concentration of A can be represented as [A] and that of B as [B]. Let the time at

which the reaction begins be the start time, that is t=0.

Let’s consider the following situation:

At t=t1,

The concentration of A=[A]1

The Concentration of B=[B]1

At t=t2,

The concentration of A=[A]2

The concentration of B=[B]2

Now we want to know the rate at which A (reactant) is disappearing and the rate at which the product B is appearing in the time interval

between t1 and t2. Therefore,

The rate of Disappearance of A = [A]2–[A]1]t2–t1=–Δ[A]Δt

The negative sign shows that the concentration of A is decreasing.

Similarly,

Rate of disappearance of B = [B]2–[B]1]t2–t1=–Δ[B]Δt

Since A is the only reactant involved in the reaction and B is the only product that is formed and as mass is conserved, the amount of A

disappeared in the time interval Δt will be same as the amount of B formed during the same time interval. So we can say that

The rate of reaction = – Rate of disappearance of A = Rate of appearance of B](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-1-2048.jpg)

![2/21

Therefore, Rate of Reaction = −Δ[A]Δt=Δ[B]Δt

The above terms for the rate of disappearance of A and rate of appearance of B are average rates of reaction. These rates give the rate of

reaction for the entire time interval Δt and hence are called average rates of reaction.

Instantaneous Rate of Reaction

What if we want to know the rate at which the reaction discussed above is proceeding at any instant of time and not for a given period of

time? The average reaction rate remains constant for a given time period so it can certainly not give any idea about the rate of reaction at a

particular instant.

This is where the instantaneous rate of reaction comes into the picture. Instantaneous rate of reaction is the rate at which the reaction is

proceeding at any given time.

Suppose the value of the term Δt is very small and tends to zero. Now, we have an infinitesimally small Δt which is a very small time

period and can be considered a particular instant of time. The average reaction rate will be the instantaneous rate of reaction.

Mathematically,

Average Rate of Reaction = −Δ[A]Δt=Δ[B]Δt

When Δt →0

Instantaneous Rate of Reaction = −Δ[A]dt=Δ[B]dt

Instantaneous Rate of Reaction = −d[A]dt=d[B]dt

The unit of rate of reaction is given by concentration/time that is (mol/L)/sec.

Read more: Rate of Reaction

Problem 1: In the reaction N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3, it is found that the rate of disappearance of N2 is 0.03 mol l-1 s-1. Calculate, the rate of

disappearance of H2, rate of formation of NH3 and rate of the overall reaction.

Solution:

N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3

The rates can be connected as,

r=frac{-dleft[ {{N}_{2}} right]}{dt}=frac{-1}{3}frac{dleft[ {{H}_{2}} right]}{dt}=frac{1}{2}frac{dleft[ N{{H}_{3}} right]}

{dt}r=dt−d[N2]=3−1dtd[H2]=21dtd[NH3]

Given:

frac{dleft[ {{N}_{2}} right]}{dt}=0.03mol,{{l}^{-1}}{{s}^{-1}}dtd[N2]=0.03moll−1s−1

Therefore, overall rate (r) = 0.03 mol l-1 s-1

Rate of disappearance of H2 left( frac{dleft[ {{H}_{2}} right]}{dt}=frac{3dleft[ {{N}_{2}} right]}{dt} right)=0.09,mol,

{{l}^{-1}}{{s}^{-1}}(dtd[H2]=dt3d[N2])=0.09moll−1s−1

Rate of formation of N{{H}_{3}}frac{dleft[ N{{H}_{3}} right]}{dt}=frac{2dleft[ {{N}_{2}} right]}{dt}NH3dtd[NH3]=dt2d[N2]

N{{H}_{3}}frac{dleft[ N{{H}_{3}} right]}{dt}=frac{2dleft[ {{N}_{2}} right]}{dt}=0.06,mol,{{l}^{-1}}{{s}^{-1}}NH3dtd[NH3]

=dt2d[N2]=0.06moll−1s−1

Solved Questions

1. What is the rate of reaction?

Solution:

Rate of the reactions is defined as the rate at which the concentration is changing or the ratio of change in concentration and change in

time

r=frac{Delta left[ C right]}{Delta t}r=ΔtΔ[C]

r → rate, Δ[C] → change in concentration

Δt → change in time.

2. What is the relation between the rate of the overall reaction, rate of formation of products and rate of disappearance

of reactants?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-2-2048.jpg)

![3/21

Solution:

Let aA + bB → cC + dD be a reaction, then

r=frac{-1}{a}frac{dleft[ A right]}{dt}=frac{-1}{b}frac{dleft[ B right]}{dt}=frac{+1}{c}frac{dleft[ C right]}{dt}=frac{+1}

{d}frac{dleft[ D right]}{dt}r=a−1dtd[A]=b−1dtd[B]=c+1dtd[C]=d+1dtd[D]

Where r → rate of the overall reaction

frac{-dleft[ A right]}{dt}todt−d[A]→rate of disappearance of A

frac{-dleft[ B right]}{dt}todt−d[B]→rate of disappearance of B

frac{-dleft[ D right]}{dt}todt−d[D]→rate of formation of D

frac{+dleft[ C right]}{dt}todt+d[C]→rate of formation of C

3. What are average and instantaneous rates?

Solution:

The average rate is calculated by taking a finite time period whereas the instantaneous rate is calculated for a time period that is almost

tending to zero. Graphically, the slope of the graph between concentration vs time gives the average rate and tangent of a point gives

instantaneous rate.

{{r}_{avg}}=frac{Delta left[ C right]}{Delta t},,,{{r}_{inst}}=frac{dleft[ C right]}{dt},,or,,underset{Delta tto 0}

{mathop{lim }},frac{Delta left[ C right]}{Delta t}ravg=ΔtΔ[C]rinst=dtd[C]orΔt→0limΔtΔ[C]

4. Calculate the rate of disapperence for of N2 in the following reactions.

N2(g) + 3H2(g) → 2NH3(g)

Given: The rate of disappearance of hydrogen gas is 0.74M/sec.

Solution:

The rate of disappearance of N2 is 1/3 the rate of disappearance of hydrogen gas

0.74 × (1/3) = 0.247 M/s.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the difference between the chemical kinetics of the reaction and chemical balancing of the equation?

Answer:

The chemical kinetics of the reaction gives details about the reaction mechanism and reaction rate, whereas, a balanced chemical equation

gives information about the stoichiometry of the reaction.

2. Why does the reaction rate increases with increasing temperature?

Answer:

With increasing the temperature of the reaction, average kinetic energy of the ions and molecules are increased due to this collision

between the ions and molecules are more often.

Factors Affecting The Reaction Rate

The rate of a reaction can be altered if any of the following parameters are changed.

Concentration of Reactants

According to collision theory, which is discussed later, reactant molecules collide with each other to form products. If the concentration of

reactants is increased, the number of colliding particles will increase thereby, increasing the rate of reaction.

Temperature

If the temperature is increased, the number of collisions between reactant molecules per second (frequency of collision). Increases,

thereby increasing the rate of the reaction. But depending on whether the reaction is an endothermic or exothermic increase in

temperature increases the rate of forward or backward reactions respectively.

In a system where more than one reaction is possible, the same reactants can produce different products under different temperature

condition.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-3-2048.jpg)

![4/21

At 100 0C in the presence of dilute sulphuric acid, diethyl ether is formed from ethanol.

2CH3CH2OH → CH3CH2OCH2CH3+H2O

At 180 0C in the presence of dilute sulphuric acid, ethylene is the major product.

CH3CH2OH → C2H4+H2O

Phase And Surface Area of Reactants

When two or more reactants are in the same phase of fluid, their particles collide more often than when either or both are in solids phase

or when they are in a heterogeneous mixture. In a heterogeneous medium, the collision between the particles occurs at an interface

between

phases. Compared to the homogeneous case, the number of collisions between reactants per unit time is significantly reduced, and so is the rea

Effect Of Solvent

The nature of the solvent also depends on the reaction rate of the solute particles.

Example:

When sodium acetates react with methyl iodide it gives methyl acetate and sodium iodide.

CH3CO2Na(sol)+CH3I(liq)→CH3CO2CH3(sol)+NaI(sol)

The above reaction occurs more faster in organic solvents such as DMF (dimethylformamide) than in CH3OH (methanol), because

methanol is able to form a hydrogen bond with CH3CO2 – but DMF is not possible.

Catalyst

Catalysts alter the rate of the reaction by changing the reaction mechanism. There are two types of catalysts namely, promoters and

poisons which increase and decrease the rate of reactions respectively.

Read More: Catalyst

For all the above factors, quantification is done in the following sections. We will try to establish a mathematical relationship between the

above parameters and rate.

Problem 1: In the reaction N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3, it is found that the rate of disappearance of N2 is 0.03 mol l-1 s-1. Calculate, the rate of

disappearance of H2, rate of formation of NH3 and rate of the overall reaction.

Intensity of Light

Even the intensity of light affects the rate of reaction. Particles absorb more energy with the increase in the intensity of light thereby

increasing the rate of reaction.

Pressure factor

Pressure increases the concentration of gases which in turn results in the increase of the rate of reaction. The reaction rate increases

in the direction of less gaseous molecules and decreases in the reverse direction.

Thus, it can be understood that pressure and concentration are interlinked and that they both affect the rate of reaction.

Rate Law and Rate Constants

What is the Rate Law?

The rate law (also known as the rate equation) for a chemical reaction is an expression that provides a relationship between the rate of the

reaction and the concentrations of the reactants participating in it.

Expression

For a reaction given by:

aA + bB → cC + dD

Where a, b, c, and d are the stoichiometric coefficients of the reactants or products, the rate equation for the reaction is given by:

Rate ∝ [A]x[B]y ⇒ Rate = k[A]x[B]y

Where,

[A] & [B] denote the concentrations of the reactants A and B.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-4-2048.jpg)

![5/21

x & y denote the partial reaction orders for reactants A & B (which may or may not be equal to their stoichiometric coefficients a &

b).

The proportionality constant ‘k’ is the rate constant of the reaction.

It is important to note that the expression of the rate law for a specific reaction can only be determined experimentally. The rate law

expression cannot be obtained from the balanced chemical equation (since the partial orders of the reactants are not necessarily equal to

the stoichiometric coefficients).

Reaction Orders

The sum of the partial orders of the reactants in the rate law expression gives the overall order of the reaction.

If Rate = k[A]x[B]y ; overall order of the reaction (n) = x+y

The order of a reaction provides insight into the change in the rate of the reaction that can be expected by increasing the concentration of

the reactants. For example:

If the reaction is a zero-order reaction, doubling the reactant concentration will have no effect on the reaction rate.

If the reaction is of the first order, doubling the reactant concentration will double the reaction rate.

In second-order reactions, doubling the concentration of the reactants will quadruple the overall reaction rate.

For third-order reactions, the overall rate increases by eight times when the reactant concentration is doubled.

Rate Constants

Rearranging the rate equation, the value of the rate constant ‘k’ is given by:

k = Rate/[A]x[B]y

Therefore, the units of k (assuming that concentration is represented in mol.L-1 or M and time is represented in seconds) can be

calculated via the following equation.

k = (M.s-1)*(M-n) = M(1-n).s-1

The units of the rate constants for zero, first, second, and nth-order reactions are tabulated below.

Reaction Order Units of Rate Constant

0 M.s-1 (or) mol.L-1.s-1

1 s-1

2 M-1.s-1 (or) L.mol-1.s-1

n M1-n.s-1 (or) L(-1+n).mol(1-n).s-1

Differential Rate Equations

Differential rate laws are used to express the rate of a reaction in terms of the changes in reactant concentrations (d[R]) over a small

interval of time (dt). Therefore, the differential form of the rate expression provided in the previous subsection is given by:

-d[R]/dt = k[A]x[B]y

Differential rate equations can be used to calculate the instantaneous rate of a reaction, which is the reaction rate under a very small-time

interval. It can be noted that the ordinary rate law is a differential rate equation since it offers insight into the instantaneous rate of the

reaction.

Integrated Rate Equations

Integrated rate equations express the concentration of the reactants in a chemical reaction as a function of time. Therefore, such rate

equations can be employed to check how long it would take for a given percentage of the reactants to be consumed in a chemical reaction.

It is important to note that reactions of different orders have different integrated rate equations.

Integrated Rate Equation for Zero-Order Reactions

The integrated rate equation for a zero-order reaction is given by:

kt = [R0] – [R] (or) k = ([R0] – [R])/t

Where,

[R0] is the initial concentration of the reactant (when t = 0)

[R] is the concentration of the reactant at time ‘t’

k is the rate constant](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-5-2048.jpg)

![6/21

Integrated Rate Equation for First-Order Reactions

The integrated rate law for first-order reactions is:

kt = 2.303log([R0]/[R]) (or) k = (2.303/t)log([R0]/[R])

Integrated Rate Equation for Second-Order Reactions

For second-order reactions, the integrated rate equation is:

kt = (1/[R]) – (1/[R0])

Solved Examples on the Rate Law

Example 1

For the reaction given by 2NO + O2 → 2NO2, The rate equation is:

Rate = k[NO]2[O2]

Find the overall order of the reaction and the units of the rate constant.

The overall order of the reaction = sum of exponents of reactants in the rate equation = 2+1 = 3

The reaction is a third-order reaction. Units of rate constant for ‘nth’ order reaction = M(1-n).s-1

Therefore, units of rate constant for the third-order reaction = M(1-3).s-1 = M-2.s-1 = L2.mol-2.s-1

Example 2

For the first-order reaction given by 2N2O5 → 4NO2 + O2 the initial concentration of N2O5 was 0.1M (at a constant

temperature of 300K). After 10 minutes, the concentration of N2O5 was found to be 0.01M. Find the rate constant of

this reaction (at 300K).

From the integral rate equation of first-order reactions:

k = (2.303/t)log([R0]/[R])

Given, t = 10 mins = 600 s

Initial concentration, [R0] = 0.1M

Final concentration, [R] = 0.01M

Therefore, rate constant, k = (2.303/600s)log(0.1M/0.01M) = 0.0038 s-1

The rate constant of this equation is 0.0038 s

-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-6-2048.jpg)

![8/21

The number of ions or molecules that take part in the

rate-determining step is known as molecularity.

The sum of powers to which the reactant concentrations are raised in the

rate law equation is known as the order of the reaction.

It is always a whole number It can either be a whole number or a fraction

The molecularity of the reaction is determined by looking

at the reaction mechanism

The order of the reaction is determined by the experimental methods

The molecularity of the reaction is obtained by the rate-

determining step

The order of the reaction is obtained by the sum of the powers to which the

reactant concentrations are raised in the rate law equation

What is a Zero Order Reaction?

Zero-order reaction is a chemical reaction wherein the rate does not vary with the increase or decrease in the

concentration of the reactants. Therefore, the rate of these reactions is always equal to the rate constant of the

specific reactions (since the rate of these reactions is proportional to the zeroth power of reactants

concentration).

Differential and Integral Form of Zero Order Reaction

The Differential form of a zero order reaction can be written as:

Rate = −dAdt=k[A]0=k

Where ‘Rate’ refers to the rate of the reaction and ‘k’ is the rate constant of the reaction.

This differential form can be rearranged and integrated on both sides to get the required Integral form as shown below.

Rate = −d[A]0dt=k

Multiplying both sides with ‘-dt’, we get:

d[A]=−kdt

Integrating on both sides, we get:

∫[A][A]0d[A]=−∫t0kdt

Where [A]0 is the initial concentration of the reactant [A] at time t=0. Solving for [A], we get:

[A]=[A0]–kt

Half-Life of a Zero Order Reaction

The timescale in which there is a 50% reduction in the initial population is referred to as half-life. Half-life is denoted by the symbol ‘t1/2’.

From the integral form, we have the following equation

[A]=[A0]–kt

Replacing t with half-life t1/2 we get:

12[A]=[A0]–kt1/2

Therefore, t1/2 can be written as:

kt1/2=12[A]0

And,

t1/2=12k[A]0

It can be noted from the equation given above that the half-life is dependent on the rate constant as well as the reactant’s initial

concentration.

Read more:

Zero Order Reaction, Half life of Different order of reaction

First-Order Reactions

What is a First-Order Reaction?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-8-2048.jpg)

![9/21

A first-order reaction can be defined as a chemical reaction in which the reaction rate is linearly dependent on the concentration of only

one reactant. In other words, a first-order reaction is a chemical reaction in which the rate varies based on the changes in the

concentration of only one of the reactants. Thus, the order of these reactions is equal to 1.

Examples of First-Order Reactions

SO2Cl2 → Cl2 + SO2

2N2O5 → O2 + 4NO2

2H2O2 → 2H2O + O2

Read more: Chemical Kinetics, First order Reaction

Differential Rate Law for a First-Order Reaction

A differential rate law can be employed to describe a chemical reaction at a molecular level. The differential rate expression for a first-

order reaction can be written as:

Rate = -d[A]/dt = k[A]1 = k[A]

Where,

‘k’ is the rate constant of the first-order reaction, whose units are s-1.

‘[A]’ denotes the concentration of the first-order reactant ‘A’.

d[A]/dt denotes the change in the concentration of the first-order reactant ‘A’ in the time interval ‘dt’.

Integrated Rate Law for a First-Order Reaction

Integrated rate expressions can be used to experimentally calculate the value of the rate constant of a reaction. In order to obtain the

integral form of the rate expression for a first-order reaction, the differential rate law for the first-order reaction must be rearranged as

follows.

−d[A]dt=k[A] ⇒d[A][A]=−kdt

Integrating both sides of the equation, the following expression is obtained.

∫[A][A]0d[A][A]=−∫tt0kdt

Which can be rewritten as:

∫[A][A]01[A]d[A]=−∫tt0kdt

Since ∫1x=ln(x), the equation can be rewritten as follows:

ln[A] – ln[A]0 = -kt

ln[A] = -kt + ln[A]0 (or) ln[A] = ln[A]0 – kt

Raising each side of the equation to the exponent ‘e’ (since eln(x) = x), the equation is transformed as follows:

eln[A]=eln[A]0–kt

Therefore,

[A]=[A]0e−kt

This expression is the integrated form of the first-order rate law.

Graphical Representation of a First-Order Reaction

The concentration v/s time graph for a first-order reaction is provided below.

For first-order reactions, the equation ln[A] = -kt + ln[A]0 is similar to that of a straight line (y =

mx + c) with slope -k. This line can be graphically plotted as follows.

Thus, the graph for ln[A] v/s t for a first-order reaction is a straight line with slope -k.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-9-2048.jpg)

![10/21

Half-Life of a First-Order Reaction

The half-life of a chemical reaction (denoted by ‘t1/2’) is the time taken for the initial concentration of the reactant(s) to reach half of its

original value. Therefore,

At t = t1/2 , [A] = [A]0/2

Where [A] denotes the concentration of the reactant and [A]0 denotes the initial concentration of the reactant.

Substituting the value of A = [A]0/2 and t = t1/2 in the equation [A] = [A]0 e-kt:

[A]02=[A]0e−kt1/2 ⇒12=e−kt1/2

Taking the natural logarithm of both sides of the equation in order to eliminate ‘e’, the following equation is obtained.

ln(12)=−kt1/2 ⇒t1/2=0.693k

Thus, the half-life of a first-order reaction is equal to 0.693/k (where ‘k’ denotes the rate constant, whose units are s-1).

Read More: Zero order reaction, First order reaction, Second order Reaction, Third order Reaction, Half life of chemical reaction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-10-2048.jpg)

![12/21

Read more:

Pseudo first order reaction

What is a Second Order Reaction?

From the rate law equations given above, it can be understood that second order reactions are chemical reactions which depend on

either the concentrations of two first-order reactants or the concentration of one-second order reactant.

Since second order reactions can be of the two types described above, the rate of these reactions can be generalized as follows:

r = k[A]x[B]y

Where the sum of x and y (which corresponds to the order of the chemical reaction in question) equals two.

Read More: Zero order reaction, First order reaction, Second order Reaction, Third order Reaction, Half

life of chemical reaction

Examples of Second Order Reactions

A few examples of second order reactions are given below:

H++OH−→H2O C+O2→CO+O

The two examples given above are the second order reactions depending on the concentration of two

separate first order reactants.

2NO2→2NO+O2 2HI→I2+H2

These reactions involve one second order reactant yielding the product.

Differential and Integrated Rate Equation for Second Order Reactions

Considering the scenario where one second order reactant forms a given product in a chemical reaction, the

differential rate law equation can be written as follows:

−d[R]dt=k[R]2

In order to obtain the integrated rate equation, this differential form must be rearranged as follows:

d[R][R]2=−kdt

Now, integrating on both sides in consideration of the change in the concentration of reactant between time

0 and time t, the following equation is attained.

∫[R]t[R]0d[R][R]2=−k∫t0dt

From the power rule of integration, we have:

∫dxx2=−1x+C

Where C is the constant of Integration. Now, using this power rule in the previous equation, the following

equation can be attained.

1[R]t–1[R]0=kt

Which is the required integrated rate expression of second order reactions.

Graph of a Second Order Reaction

Generalizing [R]t as [R] and rearranging the integrated rate law equation of reactions of the second order, the

following reaction is obtained.

1[R]=kt+1[R]0

Plotting a straight line (y=mx + c) corresponding to this equation (y = 1/[R] , x = t , m = k , c = 1/[R]0)

It can be observed that the slope of the straight line is equal to the value of the rate constant, k.

Half-Life of Second-Order Reactions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-12-2048.jpg)

![13/21

The half-life of a chemical reaction is the time taken for half of the initial amount of reactant to undergo the

reaction.

Therefore, while attempting to calculate the half life of a reaction, the following substitutions must be made:

[R]=[R]02

And, t=t1/2

Now, substituting these values in the integral form of the rate equation of second order reactions, we get:

1[R]02–1[R]0=kt1/2

Therefore, the required equation for the half life of second order reactions can be written as follows.

t1/2=1k[R]0

This equation for the half life implies that the half life is inversely proportional to the concentration of the

reactants.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-13-2048.jpg)

![14/21

What is Third Order Reaction?

A third-order reaction is a chemical reaction where the rate of reaction is proportional to the concentration of each reacting molecules. In

this reaction, the rate is usually determined by the variation of three concentration terms.

For example, let us consider a chemical reaction where,

A+2B ⇢ C+D

According to rate formula,

Rate, R= k [A]ˣ [B]ʸ

Here, the order with respect to A is given by x and order with respect to B is given by y. So the complete order of the reaction is the sum of

x and y.

For a third-order reaction, the order of the chemical reaction will be 3.

Let aA+bB+cC ⇢ Product

By rate formula, R= k [A]ˣ [B]ʸ [C]□

The third-order reaction for the above chemical reaction is given by,

Order = x+y+z

To summarize, the order of reaction can be defined as the sum of the exponents of all the reactants present in that chemical reaction. If

the order of that reaction is 3, then the reaction is said to be a third-order reaction.

Third Order Reaction Examples

● Let us consider the reaction between nitric oxide and chloride

2 NO +Cl2 ⇢ 2 NOCl

Rate, R= k[NO]2 [Cl2]

Order of above reaction =Sum of exponent of nitric oxide and chloride Order = 2 + 1 = 3

● Let us consider the reaction between nitric oxide and oxygen

2 NO + O2 ⇢ 2 NO2 R= k[NO]2 [O2]

Order = 2 + 1 = 3

The unit of third-order reaction when a rate is constant is given by, Rate of reaction= k[Reactant]³

Unit of rate is given by,

R = mol/ Ls = mol L⁻¹ s⁻¹ mol L⁻¹ s⁻¹ = k ( mol L⁻¹ )³ k =L² mol⁻² s⁻¹](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/energy-gateway-210430080802/75/Energy-gateway-blogspot-com-chemical-kinetics-complete-note-14-2048.jpg)