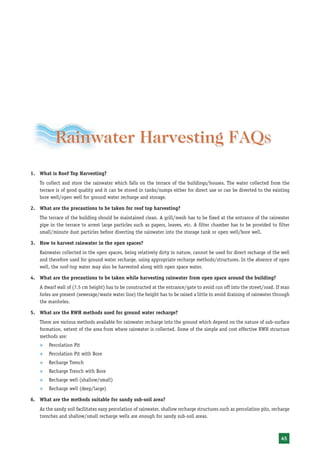

This document provides an overview of rainwater harvesting and discusses its growing importance globally. It notes that rapid population growth and urbanization are exacerbating water scarcity issues around the world. Rainwater harvesting provides multiple benefits, such as improving groundwater quality, mitigating drought effects, and reducing erosion. It can be an ideal solution in areas with inadequate water resources. The document discusses demographic trends driving increased urbanization, especially in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. It provides examples of water access issues facing cities in different regions. The benefits of rainwater harvesting for both rural and urban communities are outlined. These include improving water access and quality as well as reducing energy use. The growing interest in rainwater harvesting globally over the past few

![References

65. Texas water- water facts-....

www.tpood.state.tx.us/texaswater/sb1/primer/primer1/oof-rain-waterharvesting.htm

66. Source book of alternative technologies for freshwater..

www.unep.or.jp/ietc/publications/techpublications/techpub-se

67. Rainwater harvesting in tamil nadu....

http://www.sciseek.com/dir/environment/water-resources/rainwater-hav/index.shtml

68. Preliminary study of rainwater harvesting in mid west uganda...

www.eng.warcrick.ac.uk.dtu/pubs/up/up45/001cov.html

69. Duryog nivaran : publications...

www.adpc.ait.ac.th/duryog/publications

70. Rainwater harvesting - media. to tackle the problem of drought...

www.teriin.org/energy/waterhar.htm

71. Rainwater harvesting is decentralised...

www.verhnizen-ww.com/html/wh.html

72. International center for integrated mountain development, Rainwater harvesting system - key solution to a

looming crisis

http://www.%20icimod.org.sg/publications/newsletter/news%2036/rain.htm

73. Information on the history of water harvesting methodologies in tamilnadu and the modern methods adopted

for rainwater harvesting structures and advised by TWAD Board for both the individuals & professionals.

http://www.aboutrainwaterharvesting.com/

74. Drip irrigation system. Rainwater harvesting: a new water source by Jan ... popularity in a new way. Rainwater

harvesting is enjoying a renaissance ... biblical times. Extensive rainwater harvesting apparatus existed 4000 years ...

http://twri.tamu.edu/twripubs/WtrSavrs/v3n2/article-1.html

75. Has the mandate for the “Regulation and Control of Ground Water Development and Management” in the country...

http://www.cgwaindia.com/

76. A beautiful example on rainwater harvesting done by Mr. Krishna, an Oregon resident. Portland receives 4 feet of

rainfall anually. His 1200 squarefeet house captures on average 3600 cubit...

http://www.rdrop.com/users/krishna/rainwatr.htm

77. Rainwater harvesting the rainwater harvesting system at casa del agua channels rainfall for ... evaporative

cooler. Elements of Casa’s Rooftop Rainwater Harvesting Rooftop Catchment Size

http://ag.arizona.edu/OALS/oals/dru/waterharvesting.html

78. Rainwater harvesting in honduras technical description the harvesting of water ... bibliography schiller, ej, and

bg latham. 1995. Rainwater harvesting systems. Santiago, chile, paho/cepis. This page last updated

http://www.oas.org/SP/PROG/chap5_1.htm

79. Rainwater harvesting, or collecting rainwater for ... use on their farms and ranches. Rainwater harvesting is a

major source of drinking ... The second component of rainwater harvesting at desert house uses the roof

http://www.dbg.org/center_dl/rainwater_harvesting.html

80. Texas guide to rainwater harvesting texas guide to ... second edition texas guide to rainwater harvesting second

edition acknowledgments ... acknowledgments the texas guide to rainwater harvesting was developed by the

center [link will download it in pdf format.]

http://www.twdb.state.tx.us/publications/.../RainHarv.pdf

81. You are here: Home > rainwater harvesting rainwater harvesting ... ferrocement rainwater harvesting cistern

http://www.rainwaterharvesting.net/

82. Systems ltd is the uk leader in rainwater harvesting systems ... market leading supplier for rainwater harvesting

filters. We have designed rainwater harvesting systems for all types of...

http://www.rainharvesting.co.uk/

41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bluedropseries01-policymakers-120510181637-phpapp01/85/Rainwater-Harvesting-and-Utilisation-Policy-Maker-49-320.jpg)