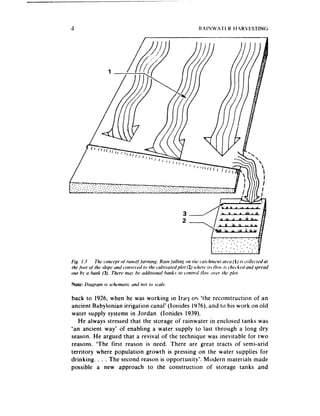

This chapter provides technical perspectives on rainwater collection. It notes that while modern water technologies focus on rivers and groundwater, these sources only account for about 40% of annual precipitation. Historically, rainwater collection was more widely used before large populations could be supported by centralized water systems. Ancient civilizations engaged in more extensive agriculture in semi-arid areas through runoff farming techniques. Research has shown that such methods supported populations in the Negev Desert over 2000 years ago. The chapter discusses traditional rainwater collection techniques from roofs and paved areas and how runoff was directed to fields. It notes renewed interest in runoff farming from research in North America, Australia, and through the Intermediate Technology movement in the UK.

![TRADITIONS IN RUNOFF FARMING 151

recognizes that while very few ‘improved’ techniques are used, ‘simple’

types of runoff farming have beet] widsspread. He cites cultivation in

depressions known as cuvettes in West Africa, and mentions the teras

used in Sudan for runoff farming by inundation. The latter, however, do

entail the construction of earthworks and might be classified as ‘improved’.

It is difficult to carry this analysis very far, however, because there have

been very few scientific studies of traditional runoff farming in Africa.

Comparable practices used in North America prior to European settlement

linger on in a few areas and have been researched in more detail. The results

are relevant in showing what features one should look for in traditional

runoff agriculture. Some of the best studies describe land occupied by the

Hopi and Papago peoples of Arizona. Rradfield (1971) notes that Hopi

fields are predominantly on alhrvial soils deposited in ‘fans’ where runoff

water flows down the sides of a valley, and gullies carrying flash floods

reach gentler slopes, depositing their sediment loads. Much of the runoff

infiltrates the soils on these fans and is held as soil moisture. Hopi farmers

can identify sites where moisture, drainage and fertility are suitable for

agriculture by noticing variations in the natural vegetation. Fields made on

such land reqGre only short lengths of bund to spread the water a little

more evenly. The sediments and organic debris deposited by floodwater are

important in maintaining soil fertility since the fields are not manured.

Indeed, commenting on Papago agriculture in the same general region,

Nabhan (1984) argues that techniques of this sort are a form of ‘nutrient

harvesting’ as well as water harvesting.

90

Fig. 6.8 Farmers in Morocco vary the werght qf seed sown per wnir area oj- land in or$er to

adapt plant dcnsi! 11

/pII) to rhc nroisrure like!, to he availahlc. In this insrance, rhe.farmer eupecrs

rhe crop growing in the depression IO benefir from runqff and has accordin.q!,b aimed fiw a higher

planr density. He has thus planned his cropping a.s a ,form qf ‘simple rul;iff .farming.

(KutJch 1982)

PD is expressed in pIanr/m’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rainwaterharvestinginruralareas-120510181422-phpapp02/85/Rainwater-Harvesting-in-Rural-Areas-168-320.jpg)