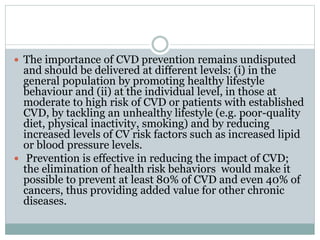

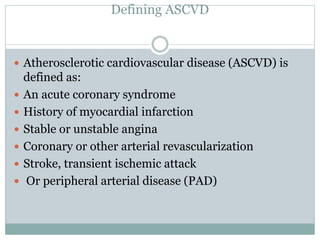

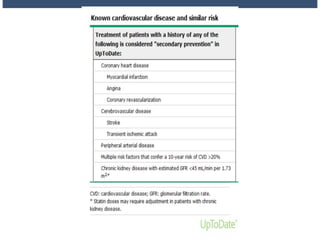

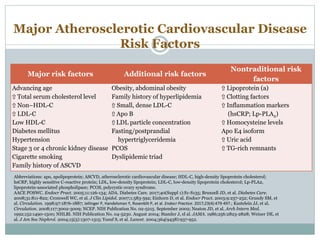

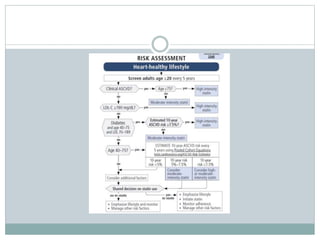

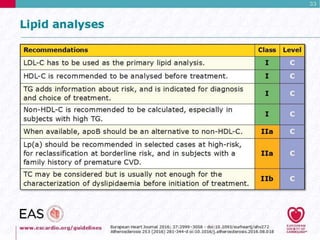

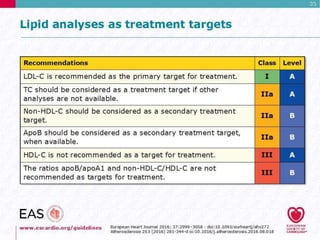

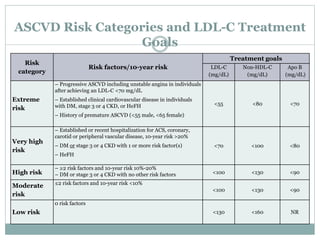

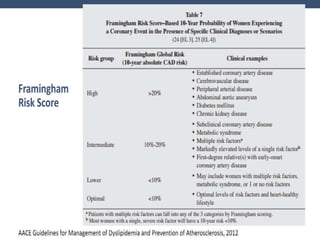

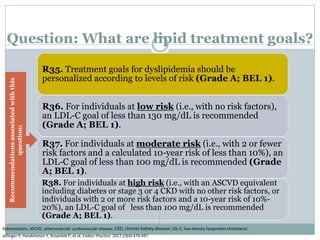

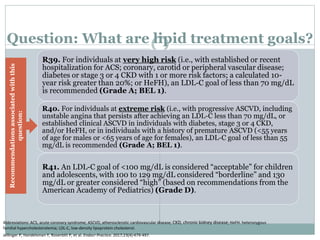

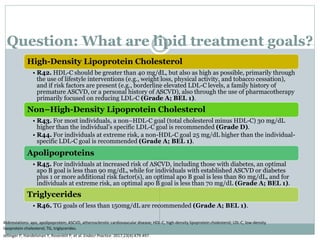

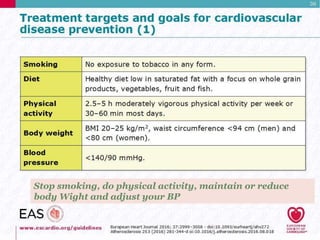

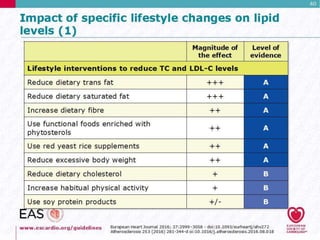

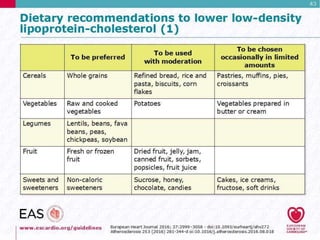

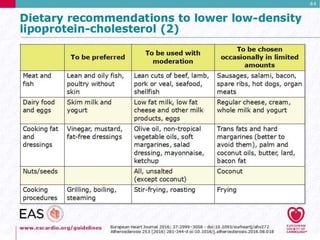

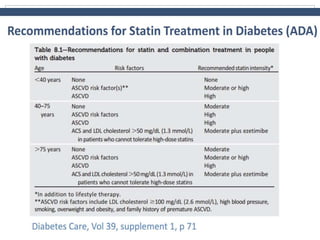

This document discusses cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention and treatment goals for dyslipidemia. It notes that CVD is a leading cause of death in Europe and prevention is important. The importance of lifestyle modifications and controlling risk factors like lipids and blood pressure is emphasized. Treatment goals for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) are personalized based on a patient's risk level, ranging from less than 130 mg/dL for low risk to less than 55 mg/dL for extreme risk. Additional goals for high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoproteins, and triglycerides are provided. Compliance with statin therapy is important for achieving benefits.

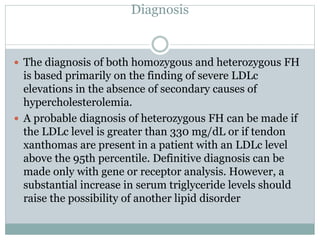

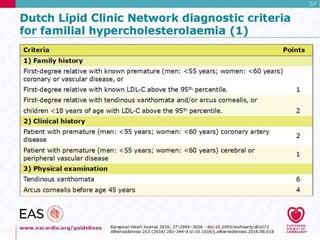

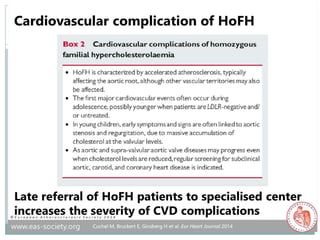

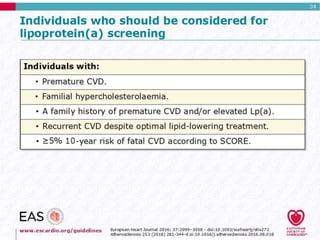

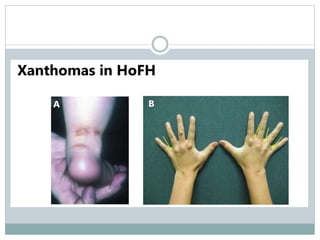

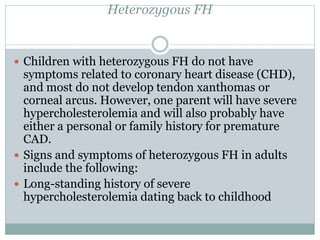

![ If no previous acute coronary event, symptoms

consistent with ischemic heart disease, especially in

the presence of other cardiovascular risk factors

(especially smoking)

Past or present symptoms of recurrent Achilles

tendonitis or arthritic complaints

If heterozygous FH is left untreated, tendon

xanthomas (Achilles tendons, metacarpophalangeal

[MCP] extensor tendons) will occur by third decade

of life in more than 60% of patients

Xanthelasmas](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyslipidaemiamok1-171031141349/85/Dyslipidaemia-highlights-46-320.jpg)