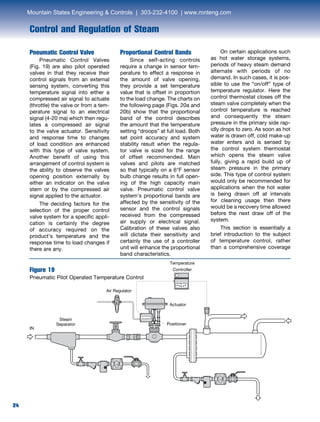

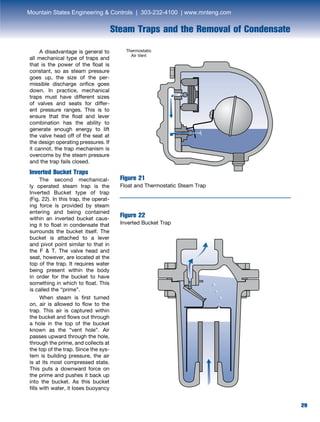

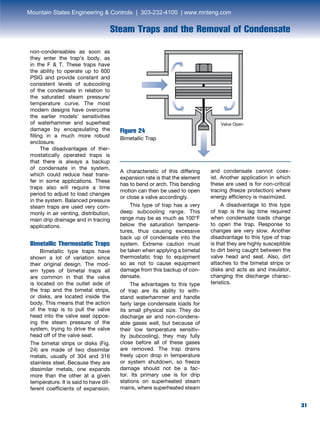

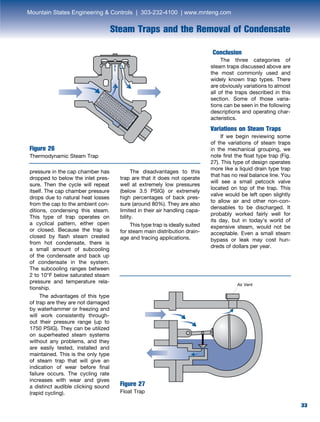

The document is a comprehensive handbook by Spirax Sarco that covers the fundamentals of steam utilization, emphasizing the efficient use of steam in industrial applications. It provides over 100 years of expertise on steam system components, including traps, controls, and condensate recovery systems to optimize performance and enhance productivity. Additionally, it serves as a resource for professionals involved in the design, operation, and maintenance of steam systems, outlining key principles, components, and best practices.