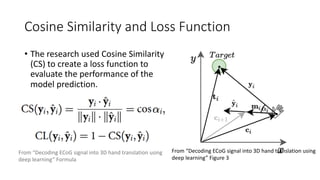

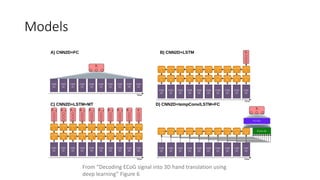

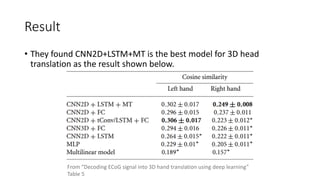

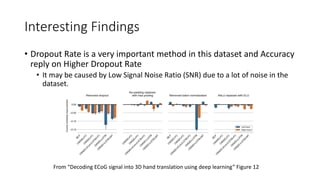

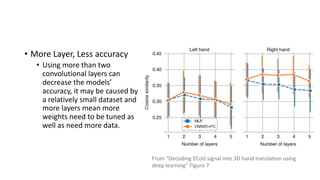

This document summarizes research using deep learning models to decode electrocorticography (ECoG) signals related to motor imagery into 3D hand translations. The research used convolutional neural networks with LSTM and multi-task learning on ECoG data from one participant to classify hand movements. The best model was able to classify movements with over 80% accuracy. However, challenges included having data from only one participant and noise in the ECoG signals. Further research with more participants could help address these challenges and generalize the results.

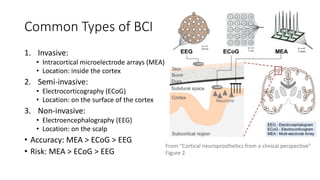

![Brain-Computer Interface (BCI)

• BCI is a device that records the signal from the brain and translates it

to a computer and vice versa.

• MI BCI is usually containing the following four components[2]:

1. Brain signal recording device.

2. Feature extraction step.

3. A decoder that translates features into actions understandable by a

computer.

4. A device that executes the commands from the decoder.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/deeplearninginbrain-computerinterface-220403035826/85/Deep-Learning-in-Brain-Computer-Interface-6-320.jpg)