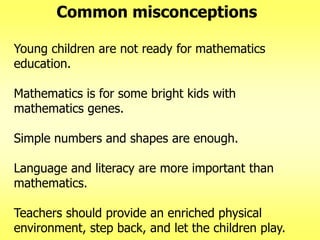

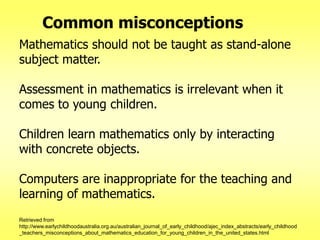

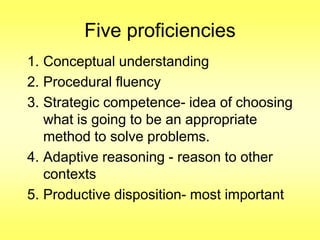

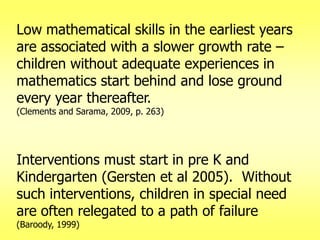

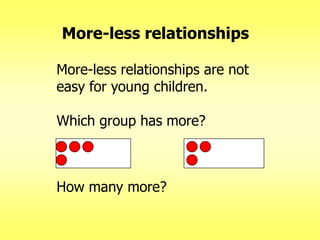

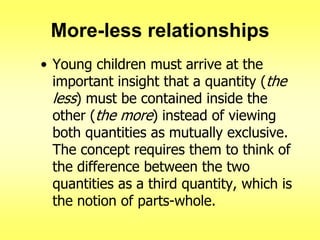

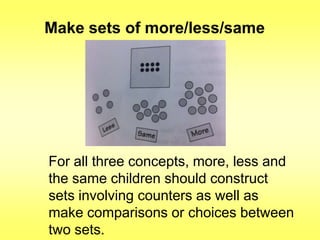

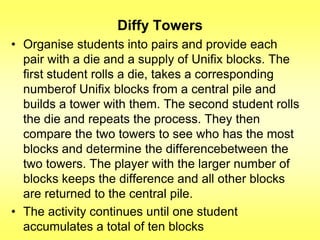

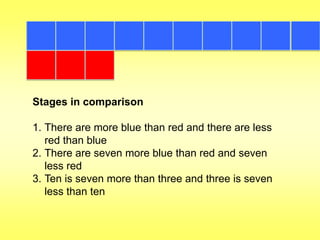

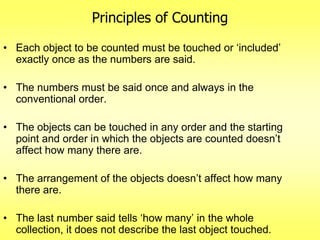

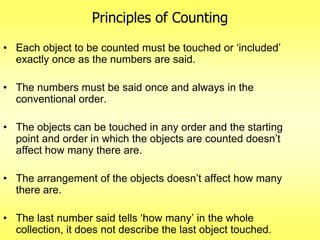

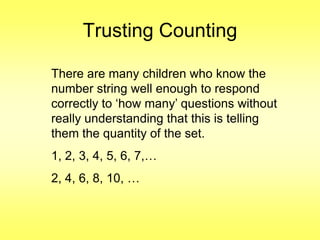

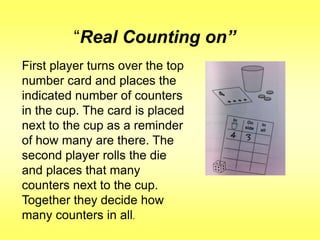

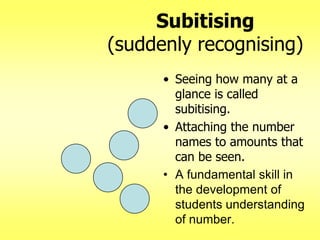

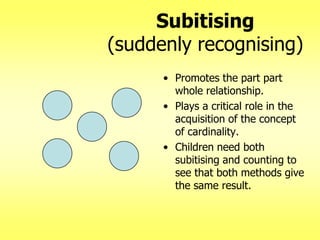

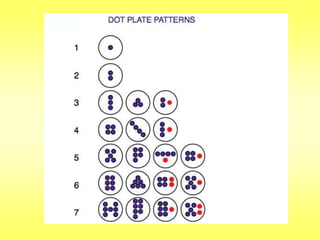

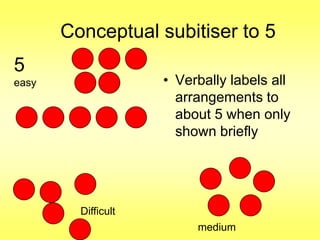

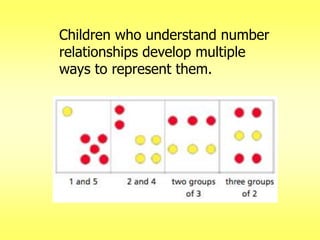

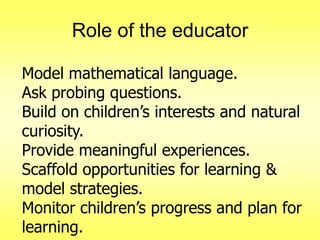

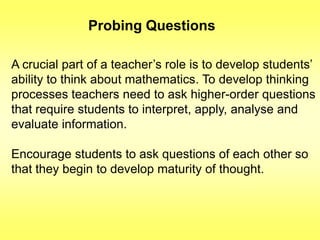

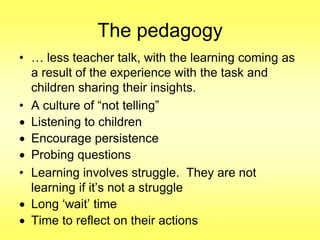

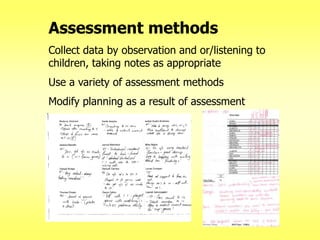

The document addresses common misconceptions about mathematics education for young children, asserting that all children are capable of engaging with mathematics, which should not be viewed as an isolated subject. It emphasizes the importance of intentional teaching practices that foster inquiry, model problem-solving, and support children's mathematical development through interactive learning experiences. Furthermore, it highlights key mathematical concepts, such as understanding more-less relationships and counting principles, essential for early number sense.