This document discusses approaches to course planning, specifically determining the level of a language course. It describes several frameworks used to define language proficiency levels, including the Australian Second Language Proficiency Ratings (ASLPR) and the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Proficiency Guidelines. These divide language ability into levels like Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, and provide descriptions of what students at each level can do. Course planners may use results from proficiency tests, learner self-assessments, and other tools to determine the target level for a course and ensure it aligns with an overall proficiency framework.

![160

7 COURSE PLANNING (1):

CONTENT-BASED, COMPETENCY-

BASED, TASK-BASED, AND TEXT-

BASED APPROACHES

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

This chapter survey the following aspects of course planning:

• Determining the level of the course

• Choosing a syllabus framework

• Content-based syllabus and CLIL

• Competency-based syllabus

• Task-based syllabus

• Text-based syllabus

Case study 11 Developing a content-based course Linsday Miller

Case study 12 A CLIL course: The Thinking Lab Science Rosa Bergadà

Case study 13 A pre-university course for international students in Australia Phil Chappell

Introduction

We suggested in Chapter 3 that the advent of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) and the

English for Special Purposes (ESP) movement marked a paradigm shift in how teaching, learning,

HUKJYYPJST^LYLUKLYZ[VVK;OPZJOHUNL^HZHSZVPUÅLUJLKI`[OLLTLYNLUJLVM[OLÄLSKVM

second language acquisition from the 1970s, from which cognitive, interactional, and sociocultural

theories of learning were proposed as alternatives to the behaviorist learning theory on which earlier

teaching methods such as audiolingualism were based. One of the outcomes of this shift was the

LTLYNLUJLVMHUTILYVMPZZLZ[OH[PUÅLUJLKUL^KPYLJ[PVUZPUJYYPJSTKLZPNU1HJVIZHUK

Farrell 2001, 2003; Richards and Rodgers 2014). Among these were the following:

• A view of language as a communicative resource that learners needed for social, occupational,

and educational purposes.

• An emphasis on learning as a social process that depends on interaction with others.

• A focus on authentic and meaningful communication as a basis for learning.

• A view of language as a resource for processing content and information.

• ([LUKLUJ`[VPU[LNYH[LKPќLYLU[ZRPSSZYH[OLY[OHU[LHJOPUN[OLZRPSSZZLWHYH[LS`

• A view of errors as a normal aspect of the language learning process.

• A move to teaching that seeks to activate and facilitate the use of learning processes and

strategies.

• .YHTTHYUKLYZ[VVKHZHJVTWVULU[VMLќLJ[P]LJVTTUPJH[PVUYH[OLY[OHUHZHUHIZ[YHJ[

system.

• A move from teacher-centered to learner-centered instruction.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-1-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 161

• (ULTWOHZPZVUKL]LSVWTLU[VMIV[OÅLUJ`HUKHJJYHJ`PUSHUNHNL

• (YLJVNUP[PVU[OH[SLHYULYZKL]LSVW[OLPYV^UYV[LZ[VSHUNHNLSLHYUPUNWYVNYLZZH[KPќLYLU[

YH[LZHUKOH]LKPќLYLU[ULLKZHUKTV[P]H[PVUZMVYSHUNHNLSLHYUPUN

• An idea of the role of classroom learning tasks and exercises as providing opportunities for

students to negotiate meaning, expand their language resources, notice how language is used,

and take part in meaningful intrapersonal exchange.

• A view of meaningful communication as the result of students processing content that is

relevant, purposeful, interesting, and engaging.

-YVT [OL Z VU^HYKZ WYPUJPWSLZ ZJO HZ [OLZL ^LYL ZLK [V ZWWVY[ H UTILY VM KPќLYLU[

approaches to the design of language courses, syllabuses, instructional methods, and resources. In

this chapter we will review two kinds of decisions that are required in planning a course: determining

the level of the course, and choosing a syllabus framework.

7.1 Determining the level of the course

In order to plan a language course, it is necessary to know the level at which the program will start

and the level that learners may be expected to reach at the end of the course. This can be referred

to as the learners’ developmental continuum (Tognolini and Stanley 2011). In the past, language

programs and commercial materials typically distinguished between elementary, intermediate, and

advanced levels, but these categories are too broad for the kind of detailed planning that program

and materials development involve.

(UHWWYVHJO[OH[OHZILLU^PKLS`ZLKPUSHUNHNLWYVNYHTWSHUUPUNPZ[VPKLU[PM`KPќLYLU[SL]LSZVM

WLYMVYTHUJLVYWYVÄJPLUJ`PU[OLMVYTVMIHUKSL]LSZVYWVPU[ZVUHWYVÄJPLUJ`ZJHSL;OLZLKLZJYPIL

^OH[ H Z[KLU[ PZ HISL [V KV H[ KPќLYLU[ Z[HNLZ VM ZLJVUK SHUNHNL KL]LSVWTLU[ ;VNUVSPUP HUK

Stanley (2011, 28–29) comment:

Many countries have now defined continua for the various subjects in terms of learning out-

comes. These outcomes typically describe what students can know and do at different stages

along the continuum. These outcomes are usually contained in syllabus documents or frame-

works and provide the basis for the development of the teaching and learning sequence and

activity (including assessment) within the subject … Generally the developmental continua

are partitioned into levels, stages, bands or grade. The grades have descriptors … that try to

capture the skills, understanding and knowledge that students have at different stages along

the developmental continuum for the subject.

(UL_HTWSLVM[OLZLVMWYVÄJPLUJ`KLZJYPW[PVUZPUSHYNLZJHSLWYVNYHTWSHUUPUN^HZ[OLHWWYVHJO

used in the Australian Migrant Education On-Arrival Program.

Choose one or two statements from the list above. What are the implications for classroom

practice?

OH[HWWYVHJOPZZLKPU`VY[LHJOPUNJVU[L_[[VKLZJYPIL[OLKPќLYLU[SL]LSZVMHJVYZL

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-2-320.jpg)

![162 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

In order to ensure that a language program is coherent and systematically moves learners

along the path towards that level of proficiency they require, some overall perspective of

the development path is required. This resulted … in the development of the Australian

Second Language Proficiency Ratings (ASLPR). The ASLPR defines levels of second language

proficiency as nine (potentially 12) points along the path from zero to native-like proficiency.

The definitions provide detailed descriptions of language behavior in all four macro-skills and

allow the syllabus developer to perceive how a course at any level fits into the total pattern of

proficiency development.

(Ingram 1982, 66)

Similarly, in the United States the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) has

WISPZOLKWYVÄJPLUJ`NPKLSPULZPU[OLMVYTVM¸BHDZLYPLZVMKLZJYPW[PVUZVMWYVÄJPLUJ`SL]LSZMVYZWLHRPUN

listening, reading, writing, and culture in a foreign language. These guidelines represent a graduated

sequence of steps that can be used to structure a foreign language program” (Liskin-Gasparro 1984,

11). The (*;-3 7YVÄJPLUJ` .PKLSPULZ have been widely promoted as a framework for organizing

curricula and as a basis for the assessment of foreign language ability. (See the information from the

¸.LULYHS WYLMHJL¹ ILSV^ HUK (WWLUKP_ MVY [OL (*;-3 7YVÄJPLUJ` .PKLSPULZ – Speaking.)

)HUK KLZJYPW[VYZ ZJO HZ [OVZL ZLK PU [OL 0,3;: L_HTPUH[PVUZ VY [OL *3,:9:( *LY[PÄJH[L PU

Communicative Skills in English (Weir 1990, 149–179) can also be used as a basis for planning learner

entry and exit levels in a program. (See Appendix 2 for an example of performance levels in Writing.)

General preface to the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines 2012

;OL(*;-37YVÄJPLUJ`.PKLSPULZHYLHKLZJYPW[PVUVM^OH[PUKP]PKHSZJHUKV^P[OSHUNHNLPU

terms of speaking, writing, listening, and reading in real-world situations in a spontaneous and

UVUYLOLHYZLKJVU[L_[-VYLHJOZRPSS[OLZLNPKLSPULZPKLU[PM`Ä]LTHQVYSL]LSZVMWYVÄJPLUJ`!

+PZ[PUNPZOLK :WLYPVY (K]HUJLK 0U[LYTLKPH[L HUK 5V]PJL ;OL THQVY SL]LSZ (K]HUJLK

Intermediate, and Novice are subdivided into High, Mid, and Low sublevels. The levels of the

(*;-3.PKLSPULZKLZJYPIL[OLJVU[PUTVMWYVÄJPLUJ`MYVT[OH[VM[OLOPNOS`HY[PJSH[L^LSS

educated language user to a level of little or no functional ability.

;OLZL.PKLSPULZWYLZLU[[OLSL]LSZVMWYVÄJPLUJ`HZYHUNLZHUKKLZJYPIL^OH[HUPUKP]PKHSJHU

and cannot do with language at each level, regardless of where, when, or how the language was

acquired. Together these levels form a hierarchy in which each level subsumes all lower levels.

The Guidelines are not based on any particular theory, pedagogical method, or educational

curriculum. They neither describe how an individual learns a language nor prescribe how an

individual should learn a language, and they should not be used for such purposes. They are an

instrument for the evaluation of functional language ability.

(ACTFL 2012)

Since the widespread adoption of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages

(CEFR), courses and tests are often referenced to the CEFR band levels in many countries. These

describe six levels of achievement divided into three broad divisions from lowest (A1) to highest (C2)

and, as we have explained elsewhere, outline what a learner should be able to do in reading, listening,

speaking, and writing at each level.

Basic user – A1, A2

Independent user – B1, B2

7YVÄJPLU[ZLY¶**

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-3-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 163

Planning a course at an appropriate level may involve the use of students’ results on international

WYVÄJPLUJ`[LZ[ZZJOHZ[OL;LZ[VM,UNSPZOHZH-VYLPNU3HUNHNL;6,-3VY0U[LYUH[PVUHS,UNSPZO

Language Testing System (IELTS). Self-assessment by the learners themselves can also play a role

(see below), as can specially designed tests, which can be used to determine the level of students’

SHUNHNLZRPSSZ0UMVYTH[PVUMYVTWYVÄJPLUJ`[LZ[Z^PSSLUHISL[OL[HYNL[SL]LSVM[OLWYVNYHT[VIL

HZZLZZLKHUKHKQZ[TLU[VM[OLWYVNYHT»ZVIQLJ[P]LZTH`ILYLXPYLKPMYLZS[ZHWWLHY[VZNNLZ[

that the program is aimed at too high or too low a level.

The role of learner self-assessment

3LHYULYZJHUHSZVILPU]VS]LKPUHZZLZZPUN[OLPYV^UWYVÄJPLUJ`SL]LSZPUKPќLYLU[ZRPSSHYLHZ

The NCSSFL-ACTFL Can-Do Statements are self-assessment checklists used by language

SLHYULYZ [V HZZLZZ ^OH[ [OL` ¸JHU KV¹ ^P[O SHUNHNL PU [OL 0U[LYWLYZVUHS 0U[LYWYL[P]L HUK

7YLZLU[H[PVUHS TVKLZ VM JVTTUPJH[PVU ;OLZL TVKLZ VM JVTTUPJH[PVU HYL KLÄULK PU [OL

5H[PVUHS:[HUKHYKZMVYZ[*LU[Y`3HUNHNL3LHYUPUN and organized in the checklist into the

following categories:

• Interpersonal (Person-to-Person) Communication

• Presentational Speaking (Spoken Production)

• Presentational Writing (Written Production)

• Interpretive Listening

• Interpretive Reading

Ultimately, the goal for all language learners is to develop a functional use of another language for

one’s personal contexts and purposes. The Can-Do Statements serve two purposes to advance

this goal: for programs, the statements provide learning targets for curriculum and unit design,

serving as performance indicators; for language learners, the statements provide a way to chart

their progress through incremental steps. The checklists are best used by learners and learning

MHJPSP[H[VYZHZWHY[VMHUV]LYHSSYLÅLJ[P]LSLHYUPUNWYVJLZZ[OH[PUJSKLZ!

• setting goals

• selecting strategies

• self-assessing

• providing evidence

• YLÅLJ[PUNILMVYLZL[[PUNUL^NVHSZ

The more learners are engaged in their own learning process, the more intrinsically motivated

they become. Research shows that the ability of language learners to set goals is linked to

PUJYLHZLKZ[KLU[TV[P]H[PVUSHUNHNLHJOPL]LTLU[HUKNYV^[OPUWYVÄJPLUJ`

(NCSSFL-ACTFL 2012)

Do you think learners can give a reliable description of their own second language abilities?

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-4-320.jpg)

![164 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

7.2 Choosing a syllabus framework

The question of a syllabus framework for a course is probably the most basic issue in course design.

.P]LU[OH[HJVYZLOHZ[VILKL]LSVWLK[VHKKYLZZHZWLJPÄJZL[VMULLKZHUK[VJV]LYHNP]LU

ZL[VMVIQLJ[P]LZHUKSLHYUPUNV[JVTLZ^OH[^PSS[OLZ`SSHIZHUKJVU[LU[VM[OLJVYZLSVVRSPRL

+LJPZPVUZHIV[Z`SSHIZHUKJVYZLJVU[LU[YLÅLJ[[OLWSHUULYZ»HZZTW[PVUZHIV[[OLUH[YLVM

language, language use, and language learning, about what the most essential elements or units of

SHUNHNLHYLHUKOV^[OLZLJHUILVYNHUPaLKHZHULѝJPLU[IHZPZMVYZLJVUKSHUNHNLSLHYUPUN

Macro- and micro-level strands in a syllabus

There will always be several layers or strands of organization in a course, and some will be more central

than others, depending on the nature of the course. For example, a writing course could potentially

be planned around any of the following units of organization: grammar (e.g., using the present tense

in descriptions), functions (e.g., describing likes and dislikes), topics (e.g., writing about world issues),

skills (e.g., developing topic sentences), processes (e.g., using prewriting strategies), tasks (e.g.,

summarizing a spoken lecture), or texts (e.g., writing a business letter). Similarly, a speaking course

could be organized around text types (small talk, conversation, interviews, discussions), functions

(expressing opinions), interaction skills (opening and closing conversations, turn taking), topics

JYYLU[HќHPYZIZPULZZ[VWPJZ+LJPZPVUZHIV[HZP[HISLZ`SSHIZMYHTL^VYRMVYHJVYZLYLÅLJ[

KPќLYLU[WYPVYP[PLZPU[LHJOPUNYH[OLY[OHUHIZVS[LJOVPJLZ;OLPZZLPZ^OPJOMVJP^PSSILJLU[YHSPU

planning the syllabus and which will be secondary? In most courses there will generally be a number

VMKPќLYLU[Z`SSHIZZ[YHUKZZJOHZgrammar linked to skills and texts, tasks linked to topics and

functions, or skills linked to topics and texts.

In making decisions about syllabus strands, it is therefore useful to distinguish between main or

macro and supportiveVYTPJYVZ[YHUKZPUHZ`SSHIZ+PќLYLU[Z`SSHIZZ[YHUKZZJOHZ[L_[Z[HZRZ

NYHTTHYJVU[LU[MUJ[PVUZHUKZRPSSZJHUILYLNHYKLKHZ[OLIPSKPUNISVJRZVMHJVYZLHUKQZ[

HZPUJYLH[PUNHIPSKPUN[OLISVJRZJHUILW[[VNL[OLYPUKPќLYLU[^H`ZHUKZHSS`HSSVM[OLTHYL

necessary at some stage in the construction process. A course which is built around multiple syllabus

strands is said to be based on an integrated syllabus, which is the approach used in most general

English adult and young-adult courses today. However, sometimes one syllabus strand will be used

as the overall planning framework for the course, that is, at the macro level of organization, and others

will be used as a minor or supportive strand of the course, that is, at the micro level.

-VY L_HTWSL H YLHKPUN JVYZL TPNO[ ÄYZ[ IL WSHUULK PU [LYTZ VM reading skills (the macro-level

planning category) and then further planned in terms of text types, vocabulary, and grammar (the

TPJYVSL]LS(SPZ[LUPUNJVYZLTPNO[ILVYNHUPaLKÄYZ[PU[LYTZVMskills, such as listening for key

words, listening for details, listening for topics at the macro level; once this level of planning has been

completed, decisions may be made about text types, topics, and vocabulary. In practical terms,

[OLYLMVYLHSSZ`SSHIZLZYLÅLJ[ZVTLKLNYLLVMPU[LNYH[PVUVMTHJYVHUKTPJYVSL]LSZVMVYNHUPaH[PVU

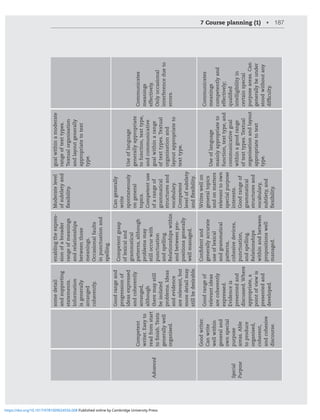

;HISLZOV^ZKPќLYLU[VW[PVUZMVYH^YP[PUNJVYZL^P[OKPќLYLU[Z`SSHIZUP[ZHZ[OLTHJYVHUK

micro-level syllabus strands.

OH[HYLZVTLKPќLYLU[^H`ZPU^OPJO[OLZ`SSHIZMVYHYLHKPUNJVYZLJVSKILVYNHUPaLK

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-5-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 165

Table 7.1 Macro and micro levels of course organization

MACRO LEVEL MICRO LEVEL

Option 1 Skills Text types

Grammar

Composing processes

Option 2 Text types Skills

Topics

Grammar

Option 3 Composing processes Text types

Grammar

Vocabulary

As language teaching has moved from grammar-based approaches to teaching to communicative

and performance-based approaches, the commonest macro-level units of organization are content,

texts, tasks, and competencies, while other organizational units such as strategies, micro-skills,

grammar, functions, and vocabulary are more typically regarded as micro-level units in a course or

Z`SSHIZ0U[OPZJOHW[LY^L^PSSYL]PL^[OLMVYTHQVYZ`SSHIZMYHTL^VYRZJYYLU[S`ZLKPUSHUNHNL

course design – content-based, competency-based, task-based, and text-based approaches. Other

syllabus types are discussed in Chapter 8.

7.3 Content-based syllabus and CLIL

A prominent current approach to course and syllabus design worldwide is known as Content-

Based Instruction or CBI and Content and Language Integrated Learning or CLIL. Content refers to

[OLPUMVYTH[PVUVYZIQLJ[TH[[LY[OH[^LSLHYUVYJVTTUPJH[L[OYVNOSHUNHNLYH[OLY[OHU[OL

language used to convey it. Of course, any language lesson involves content, whether it is a grammar

lesson, a reading lesson, or any other kind of lesson. Content of some sort has to be the vehicle that

holds the lesson or the exercise together, but in traditional approaches to language teaching, content

is selected after other decisions have been made. In other words grammar, texts, skills, functions,

etc. are the starting point in planning the lesson or the coursebook at the macro level, and after

these decisions have been made, content is selected. So, for example, a grammatical item such as

¸WYLZLU[WLYMLJ[¹TH`OH]LÄYZ[ILLUJOVZLUHZ[OLMVJZVMHSLZZVUHUKMVSSV^PUN[OPZKLJPZPVU[OL

teacher makes decisions about the kinds of topics or content to use to practice the present perfect.

P[OHJVU[LU[IHZLKHWWYVHJOKLJPZPVUZHIV[JVU[LU[HYLTHKLÄYZ[HUKV[OLYRPUKZVMKLJPZPVUZ

concerning grammar, skills, functions, etc. are made later. CBI and CLIL both use content as the

starting point in syllabus planning. As Stryker and Leaver comment (2004, 6):

The fundamental organization of the curriculum is derived from the subject matter, rather

than from forms, functions, situations, or skills. Communicative competence is acquired

during the process of learning about specific topics such as math, science, art, social studies,

culture, business, history, political systems, international affairs, or economics.

However, CBI and CLIL do not assume a particular teaching methodology, since a content-based

HWWYVHJOPZJVTWH[PISL^P[OH]HYPL[`VMKPќLYLU[[LHJOPUNTL[OVKZ*YHUKHSSZNNLZ[Z

the following kinds of materials, a description that also applies to the role of materials in CLIL:

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-6-320.jpg)

![166 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

Materials for developing the curriculum and planning CBI lessons include the use of both

authentic and adapted oral and written subject matter materials (textbooks, audio and visual

materials, and other learning materials) that are motivating and appropriate to the cognitive

and language proficiency level of the learners or that can be made accessible through bridging

activities … These activities include the use of demonstrations, visuals, charts, graphic

organizers and outlines, breaking down information into smaller chunks, pre-teaching

vocabulary, and establishing background information.

Content-based approaches are based on the following assumptions about language learning:

• People learn a language more successfully when they use the language as a means of acquiring

information, rather than as an end in itself.

• ;LHJOPUNSHUNHNL[OYVNOJVU[LU[IL[[LYYLÅLJ[ZSLHYULYZ»ULLKZMVYSLHYUPUNHZLJVUK

language because it provides a link to the real world.

• Content provides a coherent framework that can be used to link and develop all of the language

skills.

• Content can be used as the framework for a unit of work, as the guiding principle for an entire

course, as a course that prepares students for mainstreaming, as the rationale for the use of

,UNSPZOHZHTLKPTMVY[LHJOPUNZVTLZJOVVSZIQLJ[ZPUHU,-3ZL[[PUNHUKHZ[OLMYHTL^VYR

for commercial EFL/ESL materials.

While the term Content-Based Instruction has been commonly used to describe programs based on

the assumptions about language learning described above, particularly in North America, in Europe

[OLHWWYVHJOPZRUV^UHZ*303;OL[^VHWWYVHJOLZKPќLYZSPNO[S`PUMVJZ)V[O*)0HUK*303HYL

part of a growing trend in many parts of the world to use English as a medium of instruction (Graddol

2006). They have features in common, but they are not identical. CBI often involves a language

teacher teaching content through English, a language teacher working with a content teacher to

co-teach a course, or a content teacher designing and teaching a course for ESL learners. CLIL

often involves a content teacher teaching content through a second or foreign language, as does

*)0I[TH`HSZVPU]VS]LJVU[LU[MYVTZIQLJ[ZILPUNZLKPUSHUNHNLJSHZZLZ;OH[PZ[OL*303

curriculum may originate in the content class, whereas CBI tends to have as its starting point the

language requirements of a content lesson. So a CLIL lesson may start with the science teacher

HZRPUN[OLXLZ[PVU¸/V^JHU0[LHJOHTVKSLVUL]HWVYH[PVU[OYVNO,UNSPZO¹^OPSLH*)0SLZZVU

TH`Z[HY[^P[O[OLXLZ[PVU¸OH[SHUNHNL^PSSILULLKLK[V^YP[LHIV[[OLWYVJLZZVML]HWVYH[PVU

in a science lesson?”

CBI emerged somewhat organically, advocated by a number of academics and educators supported

by an extensive literature produced over a considerable period of time in the United States and other

WHY[ZVM[OL^VYSKI[^P[OV[HU`MVYTVMVѝJPHSZHUJ[PVU*303VU[OLV[OLYOHUK^HZVѝJPHSS`

proposed in a European Commission policy paper in which member states were encouraged to

develop teaching in schools through the medium of more than one language (Richards and Rodgers

2014). CLIL has been widely circulated within member states of the European community since 1994

HUKOHZILJVTLI`KLJYLL¸[OLJVYLPUZ[YTLU[MVYHJOPL]PUNWVSPJ`HPTZKPYLJ[LKH[JYLH[PUNH

TS[PSPUNHSWVWSH[PVUPU,YVWL¹+HS[VU7ќLY;OPZPZILJHZL*303^HZKL]LSVWLK[V

help promote English language skills for those who will use English as a lingua franca.

What kinds of content are your learners most interested in?

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-7-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 167

Examples of content-based courses

CBI can be used as the framework for a unit of work, as the guiding principle for an entire course,

as a course that prepares students for mainstreaming, as the rationale for the use of English as a

TLKPTMVY[LHJOPUNZVTLZJOVVSZIQLJ[ZPUHU,-3ZL[[PUNHUKHZ[OLMYHTL^VYRMVYJVTTLYJPHS

,-3,:3TH[LYPHSZ;OLZLHYLKPZJZZLKIYPLÅ`PU[YUILSV^

As the framework for a unit of work. CBI need not be the framework for an entire curriculum but

JHUILZLKPUJVUQUJ[PVU^P[OHU`[`WLVMJYYPJST-VYL_HTWSLPUHIZPULZZJVTTUPJH[PVU

course a teacher may prepare a unit of work on the theme of sales and marketing. The teacher, in

JVUQUJ[PVU^P[OHZHSLZHUKTHYRL[PUNZWLJPHSPZ[ÄYZ[PKLU[PÄLZRL`[VWPJZHUKPZZLZPU[OLHYLHVM

sales and marketing to provide the framework for the course. A variety of lessons are then developed

focusing on reading, oral presentation skills, group discussion, grammar, and report writing, all of

which are developed out of the themes and topics which form the basis of the course.

As the guiding principle for an entire course. Evans (2006) developed a content-based Animal

0ZZLZJVYZLMVYHU,UNSPZOWYVNYHTH[H1HWHULZLUP]LYZP[`;OLJVYZL¸HPTLK[VYHPZLZ[KLU[Z»

awareness of serious animal issues, deepen their knowledge about such issues, and promote the

development of critical thinking skills transferable to other courses and their nonacademic lives.” The

topics and activities used are presented in Table 7.2.

7.2 Topics and activities for a course on Animal Issues

CONTENT ACTIVITIES

1. Endangered animals • Identify causes of endangered and extinct animals

• Exchange information about two endangered species through jigsaw

listening and note-taking

2. Wildlife tracking • Rank and justify opinions with concrete reasoning

• Reach group consensus

3. Pets in society • Identify pro and con arguments

• Solve a problem as a group

4. Zoos • Compare past and current attitudes towards zoos

• Critically evaluate a zoo’s space and purpose

5. Whaling • Review the historical background and cultural underpinnings of

whaling in Japan

• Exchange information about whales and whaling through a jigsaw

reading

6. Animal research • Raise consumer awareness

• Analyze animal rights groups’ literature

The topics are chosen so that they provide a framework around which language skills, vocabulary,

and grammar can be developed in parallel.

As a course that prepares students for mainstreaming. Many courses for immigrant children in English-

speaking countries are organized around a CBI framework. For example, non-English-background

JOPSKYLUPUZJOVVSZPU(Z[YHSPHHUK5L^ALHSHUKHYLZHSS`VќLYLKHUPU[LUZP]LSHUNHNLJVYZL

to prepare them to follow the regular school curriculum with other children. Such a course might

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-8-320.jpg)

![168 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

be organized around a CBI approach. An example of this approach is described by Wu (1996) in a

program prepared for ESL students in an Australian high school. Topics from a range of mainstream

ZIQLJ[Z^LYLJOVZLUHZ[OLIHZPZMVY[OLJVYZLHUK[VWYV]PKLH[YHUZP[PVU[VTHPUZ[YLHTJSHZZLZ

Topics were chosen primarily to cater to the widest variety of students’ needs and interests. Linguistic

HWWYVWYPH[LULZZ ^HZ HUV[OLY MHJ[VY [HRLU PU[V HJJVU[ ;VWPJZ [OH[ MSÄSSLK [OLZL JYP[LYPH PUJSKL

multiculturalism, the nuclear age, sports, the Green movement, street kids, and teenage smoking.

As the rationale for the use of English as a medium for teaching some school subjects. A logical

L_[LUZPVUVM[OL*)0WOPSVZVWO`PZ[V[LHJOZVTLZJOVVSZIQLJ[ZLU[PYLS`PU,UNSPZO-VYL_HTWSLPU

some countries English is used as the medium of instruction for math and science in primary school

and also for some courses at university level. When the entire school curriculum is taught through a

foreign language, this is sometimes known as immersion education, an approach that has been used

for many years in part of English-speaking Canada.

As the framework for commercial EFL/ESL materials. The series Cambridge English for Schools

3P[[SLQVOU HUK /PJRZ ^HZ [OL ÄYZ[ ,-3 ZLYPLZ PU ^OPJO JVU[LU[ MYVT HJYVZZ [OL JYYPJST

provided the framework for the course.

Examples of CLIL-based courses

Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010, 18–22) give the following examples of how a CLIL approach can be

used at primary school (ages 5–12):

*VUÄKLUJLIPSKPUN! HU PU[YVKJ[PVU [V RL` JVUJLW[Z An example is a theme-based module on

climate change, which requires 15 hours of learning time involving class-based communication with

learners in another country. The class teacher approaches the module using CLIL-designed materials

and a networking system.

Development of key concepts and learner autonomy;OLL_HTWSLNP]LUPZZIQLJ[IHZLKSLHYUPUNVU

home economics and requires 40 hours of learning time involving trans-languaging, where activities

HYL KL]LSVWLK [OYVNO [OL *303 TVKLSZ ZPUN IPSPUNHS TH[LYPHSZ :IQLJ[ HUK SHUNHNL [LHJOLYZ

work together.

Preparation for a long-term CLIL program. An example is an interdisciplinary approach involving a set

VMZIQLJ[ZMYVT[OLUH[YHSZJPLUJLZ^OLYL[OLSLHYULYZHYLWYLWHYLKMVYPUKLW[OLKJH[PVU[OYVNO

[OL*303TVKLS:IQLJ[HUKSHUNHNL[LHJOLYZ^VYR[VNL[OLYMVSSV^PUNHUPU[LNYH[LKJYYPJST

Examples of CLIL courses at secondary level include (Coyle et al. 2010, 18–22):

Dual-school education. :JOVVSZ PU KPќLYLU[ JVU[YPLZ ZOHYL [OL [LHJOPUN VM H ZWLJPÄJ JVYZL VY

module using VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol, e.g., Skype) technologies where the CLIL language

is an additional language in both countries.

Bilingual education. 3LHYULYZZ[K`HZPNUPÄJHU[WHY[VM[OLJYYPJST[OYVNO[OL*303SHUNHNL

for a number of years with the intention of developing required content-learning goals and advanced

language skills.

Interdisciplinary module approach. ( ZWLJPÄJ TVKSL MVY L_HTWSL LU]PYVUTLU[HS ZJPLUJL VY

JP[PaLUZOPW PZ [HNO[ [OYVNO *303 PU]VS]PUN [LHJOLYZ VM KPќLYLU[ KPZJPWSPULZ LN TH[OLTH[PJZ

biology, physics, chemistry, and language).

Issues with CBI and CLIL

While both CBI and CLIL have been widely adopted in many parts of the world, implementation of

these approaches raises a number of issues.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-9-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 169

Integration of language learning and content learning. A central issue with CBI and CLIL is the extent

[V^OPJOMVJZPUNVUJVU[LU[WYV]PKLZHZѝJPLU[IHZPZMVY[OLKL]LSVWTLU[VM[OLSHUNHNLZRPSSZHUK

whether teaching content through a second language in the case of CLIL involves a dumbing down

of the content. In relation to language development, research on the use of a second language as a

medium of instruction has often revealed that when content is the primary focus, learners may bypass

grammatical accuracy and rely heavily on vocabulary and communication strategies. In planning a

course around content, decisions must still be made concerning the selection of other strands in the

Z`SSHIZZJOHZNYHTTHYMUJ[PVUZVYZRPSSZ+PќLYLU[[VWPJZTH`YLXPYLSHUNHNLVMKPќLYPUNSL]LSZ

of complexity, and as a consequence, gradation (see Chapter 2) can become a problem.

Demands on teachers. Another issue concerns whether language teachers have the necessary

ZIQLJ[TH[[LYL_WLY[PZL[V[LHJOZWLJPHSPaLKJVU[LU[HYLHZZJOHZTHYRL[PUNTLKPJPULLJVSVN`

as most language teachers have been trained to teach language as a skill rather than to teach a

JVU[LU[ZIQLJ[;LHT[LHJOPUNWYVWVZHSZPU]VS]PUNSHUNHNL[LHJOLYZHUKZIQLJ[TH[[LY[LHJOLYZ

HYLVM[LUJVUZPKLYLKU^PLSK`HUKSPRLS`[VYLKJL[OLLѝJPLUJ`VMIV[O:PTPSHYS`*303[LHJOLYZ^OV

HYLUMHTPSPHY^P[O[LHJOPUN[OLPYZIQLJ[PUH*303SHUNHNLTH`ULLKJVUZPKLYHISLWYLWHYH[PVUHUK

ongoing support. Both approaches involve assembling appropriate teaching materials and resources.

Although a recommended approach in many parts of Europe, some teachers see it as a top-down

NV]LYUTLU[PTWVZP[PVU^OPJOPZKPѝJS[[VPTWSLTLU[*VU[LU[[LHJOLYZMLLS[OL`KVUV[OH]L[OLSL]LS

VM,UNSPZOYLXPYLK[V[LHJO[OLPYZIQLJ[HUKTHU`,UNSPZO[LHJOLYZHYLJVUJLYULK[OH[[OL`KVUV[

have the knowledge base to teach content drawn from the sciences.

Evaluation learning outcomes. Lastly, a key issue is that of assessment. Will learners be assessed

according to content knowledge, language use, or both?

7.4 Competency-based syllabuses

CBI is an approach to the planning and delivery of courses that has been in widespread use since the

1970s. The application of its principles to language teaching is called Competency-Based Language

Teaching (CBLT) – an approach that has been used as the basis for the design of many work-related

and survival-oriented language-teaching programs for adults – programs that seek to teach learners the

basic skills they need in order to prepare them for situations they commonly encounter in everyday life.

Competencies refer to observable behaviors that are necessary for the successful completion of real-

world activities. These activities may be related to any domain of life, though they have typically been

SPURLK[V[OLÄLSKVM^VYRHUK[VZVJPHSZY]P]HSPUHUL^LU]PYVUTLU[+VJRPUN L_WSHPUZ

[OLYLSH[PVUZOPWIL[^LLUJVTWL[LUJPLZHUKQVIWLYMVYTHUJL!

A qualification or a job can be described as a collection of units of competency, each of which

is composed of a number of elements of competency. A unit of competency might be a task, a

role, a function, or a learning module. These will change over time, and will vary from context

to context. An element of competency can be defined as any attribute of an individual that

contributes to the successful performance of a task, job, function, or activity in an academic

setting and/or a work setting. This includes specific knowledge, thinking processes, attitudes,

and perceptual and physical skills. Nothing is excluded that can be shown to contribute to

performance. An element of competency has meaning independent of context and time.

It is the building block for competency specifications for education, training, assessment,

qualifications, tasks, and jobs.

/V^^VSK`VKLZJYPILZVTLVM[OLJVYLJVTWL[LUJPLZULLKLK[VILHULќLJ[P]L,UNSPZO

teacher?

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-10-320.jpg)

![170 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

P[O*)3;YH[OLY[OHUZLLRPUN[V[LHJONLULYHS,UNSPZO[OLMVJZPZVU[OLZWLJPÄJSHUNHNLZRPSSZ

ULLKLK [V MUJ[PVU PU H ZWLJPÄJ JVU[L_[ 0U KL]LSVWPUN JVTWL[LUJ` KLZJYPW[PVUZ [OL JVTWL[LUJ`

domain is broken down into smaller components and often the essential linguistic features involved are

HSZVPKLU[PÄLK;OLZ[HY[PUNWVPU[PUJVYZLWSHUUPUNPZ[OLYLMVYLHUPKLU[PÄJH[PVUVM[OL[HZRZ[OLSLHYULY

^PSS[`WPJHSS`OH]L[VJHYY`V[^P[OPUHZWLJPÄJZL[[PUNLNPU[OLYVSLVMMHJ[VY`^VYRLYZ[KLU[

tourist, tour guide, restaurant employee, or nurse) and the language demands of those tasks – a similar

approach to that used in some versions of Task-Based Instruction (see below). The competencies

ULLKLKMVYZJJLZZMS[HZRWLYMVYTHUJLHYL[OLUPKLU[PÄLKHUKZLKHZ[OLIHZPZMVYJVYZLWSHUUPUN

;VSSLMZVU WVPU[LKV[[OH[[OLHUHS`ZPZVMQVIZPU[V[OLPYJVUZ[P[LU[MUJ[PVUHSJVTWL[LUJPLZPU

VYKLY[VKL]LSVW[LHJOPUNVIQLJ[P]LZNVLZIHJR[V[OLTPKUPUL[LLU[OJLU[Y`0U[OLZ:WLUJLY

described the main areas of human activity and behavior that he recommended should form the

IHZPZMVYKL]LSVWPUNJYYPJSHYVIQLJ[P]LZ:PTPSHYS`PU )VIIP[[KL]LSVWLKJYYPJSHYVIQLJ[P]LZ

according to his analysis of the functional competencies required for adults living in the United States.

;OPZHWWYVHJO^HZWPJRLKWHUKYLÄULKHZ[OLIHZPZMVY[OLKL]LSVWTLU[VMJVTWL[LUJ`IHZLK

programs since the 1960s. For example, the following competencies were included in a popular

JVYZL MVY HKS[ Z[KLU[Z PU [OL Z KLZPNULK ¸MVY HKS[ Z[KLU[Z ^OV ULLK [V SLHYU [OL VYHS

language patterns and vocabulary needed in real-life situations” (Keltner, Howard, and Lee 1981):

Topic: Food and money

*VTWL[LUJ`VIQLJ[P]LZ! On completion of this unit the students will show orally, in writing or through

demonstration, that they are able to use the language needed to function in the following situations:

A. SHOPPING FOR FOOD

1. Identify the most common foods.

2. Ask for and locate foods.

3. Use common tables of weight and measures.

+PќLYLU[PH[LIL[^LLU[`WLZVMMVVKZ[VYLZ!KPZJVU[ZWLYTHYRL[HUKOVYZ[VYLZ

B. USING MONEY AND CHANGE

1. Use American money.

2. Ask for and receive change.

C. EATING OUT

1. Order from a menu.

2. Know how to tip.

As we noted above, competency-based frameworks have been adopted in many countries,

particularly for vocational and technical education. They are also increasingly being adopted in

national language curricula as a framework for the whole school curriculum (e.g., the Common Core

Standards in the United States, www.corestandards.org). The descriptions of the components of the

skills of speaking, reading, writing, and listening found in the CEFR are also described in terms of

competencies. For example, for the skill of listening, the performance of a learner at the basic level

(A1 and A2 of the framework) is described as follows (Council of Europe 2001, 66):

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-11-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 171

• Can understand phrases and expressions related to areas of immediate priority (e.g. very

basic personal and family information, shopping, local geography, employment), provided

speech is clearly and slowly articulated. (A1)

• Can understand enough to be able to meet needs of a concrete type, provided speech is

clearly and slowly articulated. (A2)

• Can follow speech which is very slow and carefully articulated. (A2)

We can compare this with the ability of an advanced-level listener (C1 and C2 on the CEFR):

• Has no difficulty in understanding any kind of spoken language, whether live or broadcast,

delivered at fast native speed. (C2)

• Can understand enough to follow extended speech on abstract and complex topics beyond

his/her own field, though he/she may need to confirm occasional details, especially if the

accent is unfamiliar. (C1)

• Can recognize a wide range of idiomatic expressions and colloquialisms, appreciating reg-

ister shifts. (C1)

• Can follow extended speech even when it is not clearly structured and when relationships

are only implied and not signalled explicitly. (C1)

(Council of Europe 2001, 66)

What characterizes a competency-based approach is the focus on the outcomes of learning as

the driving force of teaching and the curriculum. Hence, this is an example of a backward-design

HWWYVHJO (Z ^P[O V[OLY IHJR^HYKKLZPNU HWWYVHJOLZ UV ZWLJPÄJH[PVU PZ NP]LU HZ [V how the

competencies should be taught, and therefore the choice of methodology as well as the language

needed to achieve the competency are left to the course designer or teacher.

(LYIHJO PKLU[PÄLK LPNO[ MLH[YLZ PU]VS]LK PU [OL PTWSLTLU[H[PVU VM *)3; WYVNYHTZ PU

language teaching, particularly those with a vocational or social-survival focus.

• (MVJZVUZJJLZZMSMUJ[PVUPUNPUZVJPL[`! The goal is to enable students to become

autonomous individuals capable of coping with the demands of the world.

• (MVJZVUSPMLZRPSSZ! Rather than teaching language in isolation, CBLT teaches language as a function

VMJVTTUPJH[PVUHIV[JVUJYL[L[HZRZ:[KLU[ZHYL[HNO[QZ[[OVZLSHUNHNLMVYTZZRPSSZYLXPYLK

by the situations in which they will function. These forms are normally determined by needs analysis.

• ;HZRVYWLYMVYTHUJLVYPLU[LKPUZ[YJ[PVU! What counts is what students can do as a result of

instruction. The emphasis is on overt behaviors rather than on knowledge or the ability to talk

about language and skills.

• 4VKSHYPaLKPUZ[YJ[PVU!3HUNHNLSLHYUPUNPZIYVRLUKV^UPU[VTLHUPUNMSJOURZ6IQLJ[P]LZ

HYLIYVRLUKV^UPU[VUHYYV^S`MVJZLKZIVIQLJ[P]LZZV[OH[IV[O[LHJOLYZHUKZ[KLU[ZJHU

get a clear sense of progress.

• 6[JVTLZHYLTHKLL_WSPJP[! Outcomes are public knowledge, known and agreed upon by both

SLHYULYHUK[LHJOLY;OL`HYLZWLJPÄLKPU[LYTZVMILOH]PVYHSVIQLJ[P]LZZV[OH[Z[KLU[ZRUV^

what behaviors are expected of them.

• *VU[PUVZHUKVUNVPUNHZZLZZTLU[! Students are pre-tested to determine what skills they lack

and post-tested after instruction on that skill. If they do not achieve the desired level of mastery,

[OL`JVU[PUL[V^VYRVU[OLVIQLJ[P]LHUKHYLYL[LZ[LK

• +LTVUZ[YH[LKTHZ[LY`VMWLYMVYTHUJLVIQLJ[P]LZ! Rather than the traditional paper-and-pencil

[LZ[ZHZZLZZTLU[PZIHZLKVU[OLHIPSP[`[VKLTVUZ[YH[LWYLZWLJPÄLKILOH]PVYZ

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-12-320.jpg)

![172 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

• 0UKP]PKHSPaLKZ[KLU[JLU[LYLKPUZ[YJ[PVU!0UJVU[LU[SL]LSHUKWHJLVIQLJ[P]LZHYLKLÄULKPU

terms of individual needs; prior learning and achievement are taken into account in developing

curricula. Instruction is not time-based; students progress at their own rates and concentrate on

QZ[[OVZLHYLHZPU^OPJO[OL`SHJRJVTWL[LUJL

Examples of CBI courses

*)0OHZILLU^PKLS`ZLKPU[OLKLZPNUVMTHU`KPќLYLU[RPUKZVMJVYZLZZVTLVM^OPJOHYLV[SPULK

below.

Occupational and vocational courses. As noted above, the commonest use of CBI in course design

is in preparing work-related courses that are often built around the tasks learners need to perform in

their work situations and the competencies needed to perform the tasks.

Social-survival courses. Courses designed for immigrants and other new arrivals have often been

developed around a competency framework, grouped around situations, activities, and tasks that new

arrivals encounter and competencies related to task performance. Mrowicki (1986) described the process

of developing a competency-based curriculum for a refugee program designed to develop language skills

for employment. The process included reviewing existing curricula, resource materials, and textbooks;

needs analysis (interviews, observations, survey of employers); identifying topics for a survival curriculum;

identifying competencies for each of the topics; grouping competencies into instructional units.

Issues with Competency-Based Instruction

Although there has been a resurgence in competency-based approaches in recent years, as seen

with CEFR, for example, such approaches are not without their critics. The following issues are

commonly mentioned.

Identifying competencies. Critics such as Tollefson (1986, 1995) have argued that no valid procedures

HYLH]HPSHISL[VKL]LSVWJVTWL[LUJ`ZWLJPÄJH[PVUZ(S[OVNOSPZ[ZVMJVTWL[LUJPLZJHUILNLULYH[LK

intuitively for many areas and activities, there is no way of knowing which ones are essential. Typically,

competencies are described based on intuition and experience. In addition, focusing on observable

behaviors can lead to a trivialization of the nature of an activity.

Components of competencies. *VTWL[LUJ`Z[H[LTLU[ZHYLHSZVKPѝJS[[VVWLYH[PVUHSPaLPU[LYTZ

of their precise linguistic components, since there is no direct form-to-competence correspondence.

The realization of a competency is often to some extent unpredictable, depending on factors in

the situation: who the participants are, what their roles are, their emotional state, and so on. It is

ZPTPSHYS`KPѝJS[[VKPќLYLU[PH[LWYLJPZLS`IL[^LLUKPќLYLU[SL]LSZVMWLYMVYTHUJLVMHJVTWL[LUJ`

For example, the following are characteristics of competence in conversation at level B1 in the CEFR

(Council of Europe 2001, 76):

Can enter unprepared into conversations on familiar topics.

Can follow clearly articulated speech directed at him/her in everyday conversations, though

will sometimes have to ask for repetition of particular words and phrases.

Can maintain a conversation or discussion, but may sometimes be difficult to follow when try-

ing to say exactly what he/she would like to.

Can express and respond to feelings such as surprise, happiness, sadness, interest and indif-

ference.

However, to operationalize these statements in terms of linguistic features and processes – an

essential step in developing teaching materials or tests to teach and assess mastery of these

JVTWL[LUJPLZ¶PZSHYNLS`HZIQLJ[P]LHUKPTWYLZZPVUPZ[PJWYVJLZZ(Z3LUNJVTTLU[Z!

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-13-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 173

Quite clearly teachers will need to judge the appropriateness of the B1 descriptors (or any

others within the CEFR scales) in relation to the students they are teaching. If one is work-

ing with, say, a group of Italian-speaking bank employees learning English for professional

reasons, then some of the descriptors might make sense at some stage of their teaching.

However, if one is teaching linguistic-minority students in England who are learning to use

English to do academic studies, then these descriptors would only be, at best, appropriate in a

very vague and abstract sense; they would need to be adapted and expanded locally because

an independent user of English as a second language in school would have to do a good deal

more than what is covered in these CEFR descriptors.

;OLSHJRVMHZ`SSHIZVYZWLJPÄJH[PVUVMJVU[LU[[OH[^VSKLUHISL[OLV[JVTLZPU[OL*,-9[VIL

HJOPL]LKOHZILLUPKLU[PÄLKHZWYVISLTH[PJPUZPUN[OLMYHTL^VYRHUKOHZSLK[V[OLKL]LSVWTLU[

VM[OL,UNSPZO7YVÄSLŽWYVQLJ[HJVSSHIVYH[P]LYLZLHYJOWYVNYHTYLNPZ[LYLK^P[O[OL*VUJPSVM,YVWL

and mainly funded by Cambridge University Press and Cambridge English Language Assessment.

;OLHPTVM[OL,UNSPZO7YVÄSLWYVQLJ[PZ[VKL]LSVWH¸WYVÄSL¹VYZL[VMYLMLYLUJLSL]LSKLZJYPW[PVUZ

of the grammar, vocabulary, and functions of English linked to the CEFR. These reference-level

descriptions are intended to provide detailed information about the language that learners can be

L_WLJ[LK[VKLTVUZ[YH[LH[LHJOSL]LSVќLYPUN^OH[PZPU[LUKLKHZHJSLHYILUJOTHYRMVYWYVNYLZZ

that will inform curriculum development as well as the development of courses and test materials to

support learners, teachers, and other professionals involved in the learning and teaching of English

HZHMVYLPNUSHUNHNL-VYMY[OLYPUMVYTH[PVUZLLO[[W!^^^LUNSPZOWYVÄSLVYN

7.5 Task-based syllabus

Task-Based Instruction or TBI (also known as Task-Based Teaching) is an approach that draws

heavily on second language acquisition (SLA) theory (or at least, selections from SLA theory) and is

based on the view that successful language learning results from engagement with tasks (Van den

Branden 2006, 2012; Van den Branden, Bygate, and Norris 2009; Long 2015) rather than through

a focus on grammar or other aspects of the linguistic system. A task-based syllabus makes use of

both tasks that have been specially designed to facilitate second language learning and tasks that

resemble the kinds of tasks learners will have to accomplish or carry out in the real world. Through

JVTWSL[PUNKPќLYLU[RPUKZVM[HZRZSLHYULYZHYLZHPK[VLUNHNLPUWYVJLZZLZ[OH[MHJPSP[H[LZLJVUK

SHUNHNLKL]LSVWTLU[-VYL_HTWSL3VUNHUK*YVVRLZ JSHPTLK[OH[[HZRZ¸WYV]PKLH

vehicle for the presentation of appropriate target language samples to learners – input which they

will inevitably reshape via application of general cognitive processing capacities – and for the delivery

VM JVTWYLOLUZPVU HUK WYVKJ[PVU VWWVY[UP[PLZ VM ULNV[PHISL KPѝJS[`¹ :RLW[PJZ VM ;)0 ZLL P[ HZ

simplistic (e.g., Swan 2005), while advocates see it as solving the language-teaching problem once

and for all (Long 2015) (a refrain that has been heard many times in the past). Proponents of TBI

contrast it with earlier grammar-focused approaches to teaching such as audiolingualism, which they

JOHYHJ[LYPaLHZ¸[LHJOLYKVTPUH[LKMVYTVYPLU[LKJSHZZYVVTWYHJ[PJL¹=HUKLU)YHUKLU

;OL[OLVY`VM;)0OHZKL]LSVWLKPUKPќLYLU[KPYLJ[PVUZZPUJLP[^HZÄYZ[WYVWVZLK,HYS`JVUJLW[PVUZ

of TBI such as those above proposed tasks as a unit that could be used to activate second

language learning processes and focused primarily on acquisition of grammar through tasks. A

more appropriate name for this view of tasks would be task-based grammar instruction. Tasks were

How would you distinguish between a task and an exercise?

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-14-320.jpg)

![174 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

regarded as procedures that learners engage with which promote learning as a by-product of task

LUNHNLTLU[HUKJVTWSL[PVU(UTILYVMJYP[LYPH^LYLWYVWVZLKPUKLÄUPUNH[HZR!

• It is something that learners do or carry out, initially using their existing language resources.

• It has an outcome that is not simply linked to learning language, though language acquisition

may occur as the learner carries out the task.

• It involves a focus on meaning.

• It calls upon the learners’ use of communication strategies and interactional skills (shared tasks).

Examples of tasks from this perspective are ÄUKPUNHZVS[PVU[VHWaaSL, reading a map and giving

directions, or reading a set of instructions and assembling a toy. Tasks of this kind can be described

as pedagogic tasks ( [HZR PU ^OPJO [^V SLHYULYZ OH]L [V [Y` [V ÄUK [OL UTILY VM KPќLYLUJLZ

between two similar pictures is an example of a pedagogic task. The task itself is not something one

would normally encounter in the real world. However, the interactional processes it requires provide

useful input to language development. Other examples of tasks of this kind include the following:

• 1PNZH^[HZRZ!;OLZL[HZRZPU]VS]LSLHYULYZPUJVTIPUPUNKPќLYLU[WPLJLZVMPUMVYTH[PVU[VMVYT

H^OVSLLN[OYLLPUKP]PKHSZVYNYVWZTH`OH]L[OYLLKPќLYLU[WHY[ZVMHZ[VY`HUKOH]L[V

piece the story together).

• 0UMVYTH[PVUNHW[HZRZ!Tasks in which one student or group of students has one set of

information and another student or group has a complementary set of information. They must

ULNV[PH[LHUKÄUKV[^OH[[OLV[OLYWHY[`»ZPUMVYTH[PVUPZPUVYKLY[VJVTWSL[LHUHJ[P]P[`

• 7YVISLTZVS]PUN[HZRZ!Students are given a problem and a set of information. They must arrive

at a solution to the problem. There is generally a single resolution of the problem.

• +LJPZPVUTHRPUN[HZRZ!Students are given a problem for which there are a number of possible

outcomes and they must choose one through negotiation and discussion.

• 6WPUPVUL_JOHUNL[HZRZ!Learners engage in discussion and exchange of ideas. They do not

need to reach agreement.

7LKHNVNPJ[HZRZLUNHNL[OLZLVMZWLJPÄJPU[LYHJ[PVUHSZ[YH[LNPLZ;OL`TH`HSZVYLXPYL[OLZLVM

ZWLJPÄJ[`WLZVMSHUNHNLZRPSSZNYHTTHY]VJHISHY`/V^L]LY^OLU[OL`PUJSKLHMVJZVUSHUNHNL

development, such a focus might occur after the task has been attempted, since the linguistic demands

of the task are often to some extent unpredictable. A sequence of classroom activities is suggested that

consists of (1) pre-task activities (to prepare students for a task), (2) the task, and (3) follow-up activities

based on the language that emerged during the task (Willis 1996; Willis and Willis 2007).

(KPќLYLU[WLYZWLJ[P]LVU[HZRZTHRLZZLVM^OH[JHUILKLZJYPILKHZreal-world tasks. These are

HJ[P]P[PLZ[OH[YLÅLJ[YLHS^VYSKZLZVMSHUNHNLHUK^OPJOTPNO[ILJVUZPKLYLKHYLOLHYZHSMVYYLHS

^VYSK[HZRZ(YVSLWSH`PU^OPJOZ[KLU[ZWYHJ[PJLHQVIPU[LY]PL^^VSKILH[HZRVM[OPZRPUK;OPZ]PL^

of tasks is seen in the following description taken from the CEFR of the Council of Europe (2001, 157):

Tasks are a feature of everyday life in the personal, public, educational domains.Task accomplish-

ment by an individual involves the strategic activation of specific competencies in order to carry out

a set of purposeful actions in a particular domain with a clearly defined goal and specific outcome.

Examples of tasks of this nature include:

• PU[LYHJ[PUN^P[OHWISPJZLY]PJLVѝJPHS

• [HRPUNWHY[PUHQVIPU[LY]PL^

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-15-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 175

• purchasing something in a store;

• describing a medical problem to a doctor;

• completing a form to apply for a driver’s license;

• following written instructions to assemble something;

• reading a report and discussing its recommendations;

• replying to an email message.

Thus, while early versions of TBI proposed tasks as a unit that could be used to teach language,

i.e., they are a means to an end, later versions propose mastery of tasks as an end in itself, i.e., they

focus mainly on real-world tasks:

The design of a task-based syllabus preferably starts with an analysis of the students’ needs.

What do these students need to be able to do with the target language? What are the tasks

they are supposed to perform outside of the classroom? Using different sources and different

methods (such as interviews, observations, and surveys) a concrete description of the kinds

of tasks students will face in the real word is drawn up. This description, then, serves as the

basis for the design and sequencing of tasks in the syllabus.

(Van den Branden 2012, 134)

No matter which view of tasks one adopts, many classroom activities do not share the characteristics

of tasks as illustrated above and are best described as exercises. These include drills, cloze activities,

controlled writing activities, etc., and many of the traditional techniques that are familiar to many

teachers. With TBI the focus shifts to using tasks to create interaction, and then building language

awareness and language development around task performance. Grammar and other components of

accurate language use are addressed as and when the need for them arises during the completion

of tasks.

Examples of Task-Based Instruction

;HZRZHZHWSHUUPUNUP[PUJYYPJSTKLZPNUOH]LILLUZLKPUHUTILYVMKPќLYLU[^H`Z

As the sole framework for course planning and delivery. Such an approach was used in a program

described by Prabhu (1987) in which a grammar-based curriculum was replaced by a task-based one

in a state school system, albeit only for a short period.

As one component of a course. A task strand can also serve as one component of a course, where

it would seek to develop general communication skills. This is the approach described by Beglar and

/U[PU[OLPYZ[K`VMH^LLRJVYZLMVYZLJVUK`LHY1HWHULZLUP]LYZP[`Z[KLU[Z;OL

task strand was based on a survey. Students designed a survey form, then collected data, analyzed it,

and presented the results. In this case task is being used in ways others would use the term project.

At the same time, students were also involved in classroom work related to a direct approach to

[LHJOPUNZWLHRPUNZRPSSZYLJLP]PUNL_WSPJP[PUZ[YJ[PVUPUZVTLVM[OLZWLJPÄJZ[YH[LNPLZHUKTPJYV

skills required for conversation.

As a technique. Tasks can be used as one technique in the teacher’s repertoire and can also be used

PUJVUQUJ[PVU^P[OV[OLYHWWYVHJOLZZJOHZZRPSSIHZLKVY[L_[IHZLKVULZ

What are some of the real-world tasks your learners use English for?

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-16-320.jpg)

![176 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

Issues with task-based syllabuses

As with any innovation in curriculum design, new proposals such as TBI raise a number of issues for

JYYPJSTWSHUULYZHUKTH[LYPHSZKLZPNU:VTLVM[OLZLHYLKLZJYPILKIYPLÅ`ILSV^

+LÄUP[PVUVM[HZR+LÄUP[PVUZVM[HZRZHYLZVTL[PTLZZVIYVHKHZ[VPUJSKLHSTVZ[HU`[OPUN[OH[

involves learners doing something.

Choice and sequencing of tasks. Tomlinson (2015, 336–337) suggests that if tasks are chosen

primarily for the pedagogic potential, there is a danger that students will not acquire the language

ZRPSSZ[OL`ULLKIL`VUK[OLJSHZZYVVT/LWYVWVZLZ[OH[[HZRZ¸ZOVSKILWYLKL[LYTPULKZV[OH[

[OL`JV]LY[OLZP[H[PVUZVIQLJ[P]LZ[OLV[JVTLZ[OLZRPSSZHUK[OLZ[YH[LNPLZ^OPJOHYLYLSL]HU[[V

the learners’ post-course performance in the target language.”

Development of accuracy. ,_JLZZP]L ZL VM JVTTUPJH[P]L [HZRZ TH` LUJVYHNL ÅLUJ` H[ [OL

expense of accuracy.

Lack of relevance in an assessment-driven curriculum. Many students study English in order to pass

local or national tests, and these are typically not based on task performance.

Demands on teachers. A task-based approach is heavily dependent on the teacher’s initiative. Since

the kind of language skills a learner needs to develop cannot be predicted in advance and will depend

on his or her needs and learning context, task-based approaches are typically one-of-a-kind. Hence,

there are no general task-based syllabuses for teachers or course designers to use as a reference,

and likewise, since the approach precludes the use of a pre-designed syllabus, there are no published

courses or course materials based on this approach.

7.6 Text-based syllabus

Another way to think about the goals of language learning is to view them as a means of learning

OV^[VUKLYZ[HUKHUKZLKPќLYLU[RPUKZVMZWVRLUHUK^YP[[LU[L_[ZHUK[VWHY[PJPWH[LPUSHUNHNL

based social practices. As Mickan (2013, 1) argues:

Texts are integral to everyday life. We organize our lives and those of others with numerous

spoken and written texts – greetings, instructions, news, emails, telephone calls, calendars,

timetables and diaries. Invitations, weather forecasts, sporting programmes and televisions

shows influence our decisions, actions and events …

;L_[ZTH`IL]PL^LK[OLUHZZ[YJ[YLKUP[ZVMKPZJVYZL[OH[HYLZLKPUZWLJPÄJJVU[L_[ZPUZWLJPÄJ

ways, that is as conversations, directives, exchanges, explanations, expositions, factual recounts,

information texts, instructions, interviews, narratives, opinion texts, personal recounts, persuasive texts,

presentations, procedures. (See Appendix 3 for a list of common text types.) A text-based syllabus is

VYNHUPaLKHYVUK[OL[L_[[`WLZVJJYYPUNTVZ[MYLXLU[S`PUZWLJPÄJJVU[L_[Z;OLZLJVU[L_[ZTPNO[

include such situations as studying in an English-medium university, studying in an English-medium

WYPTHY`VYZLJVUKHY`ZJOVVS^VYRPUNPUHYLZ[HYHU[VѝJLVYZ[VYLZVJPHSPaPUN^P[OULPNOIVYZPUH

OVZPUNJVTWSL_;OLZLHYLPKLU[PÄLK[OYVNOULLKZHUHS`ZPZ[OH[PZ[OYVNO[OLHUHS`ZPZVMSHUNHNL

HUK JVTTUPJH[PVU HZ P[ VJJYZ PU KPќLYLU[ ZL[[PUNZ ;OL HZZTW[PVU ILOPUK ;)0 PZ [OH[ ZLJVUK

SHUNHNLSLHYUPUNPU]VS]LZTHZ[LYPUN[OLJVU]LU[PVUZUKLYS`PUN[OLZWLJPÄJ[`WLZVM[L_[Z[OLSLHYULYZ

encounters in his or her domains of language use – e.g., at school, work, in social situations, and so on.

Identifying these texts and their features and then building a course around them form the basis of text-

based syllabus design. Mickan (2013, 13) describes the rationale for a text-based approach as follows:

[A text approach] constructs the curriculum around social practices and their texts rather than

presenting language as grammatical and lexical objects … The ready availability of texts as

resources for teaching simplifies curriculum planning and implementation.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-17-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 177

A curriculum constructed around social practices and their texts is a curriculum designed for

learners’ engagement with meaning – not as an afterthought, but as the central activity. The

focus on texts creates potential to make meanings with other people.

A text-based approach has been used as a component of a national curriculum in some contexts.

The following are examples of the text types that were used in the national curriculum in Singapore:

7YVJLKYLZ!e.g., procedures used in carrying out a task.

,_WSHUH[PVUZ!e.g., explaining how and why things happen.

,_WVZP[PVUZ!e.g., reviews, arguments, debates.

-HJ[HSYLJVU[Z!e.g., magazine articles.

7LYZVUHSYLJVU[Z!LNHULJKV[LZKPHY`QVYUHSLU[YPLZIPVNYHWOPLZH[VIPVNYHWOPLZ

0UMVYTH[PVUYLWVY[Z!e.g., fact sheets.

5HYYH[P]LZ! e.g., stories, fables.

*VU]LYZH[PVUZHUKZOVY[MUJ[PVUHS[L_[Z!e.g., dialogs, formal/informal letters, postcards,

e-mail, notices.

The CEFR includes a far broader set of text types and lists the following as examples of texts learners

may need to understand, produce, or participate in (Council of Europe 2001, 95):

Spoken texts Written texts

• Public announcements and instructions

• Public speeches, lectures,

• Presentations, sermons

• Rituals (ceremonies, formal religious

services)

• Entertainment (drama, shows,

readings, songs)

• Sports commentaries (football,

cricket, … etc.)

• News broadcasts

• Public debates and discussion

• Interpersonal dialogues and conversations

• Telephone conversations

• Job interviews

• Books: fiction and non-fiction …

• Magazines

• Newspapers

• Instructions (e.g. DIY, cookbooks, … etc.)

• Textbooks

• Comic strips

• Brochures, prospectuses

• Leaflets

• Advertising material

• Public signs and notices

• Supermarket, shop and market-stall signs

• Packaging and labelling on goods

• Tickets, … etc.

• Forms and questionnaires

• Dictionaries (monolingual and bilingual),

thesauri

• Business and professional letters, faxes

• Personal letters

• Essays and exercises

• Memoranda, reports and papers

• Notes and messages, … etc.

• Databases (news, literature, general information)

What are some of the kinds of spoken and written texts your learners need to become

WYVÄJPLU[PU

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-18-320.jpg)

![178 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

Syllabus and course design from a text-based perspective involves identifying the spoken and written

text types most relevant to the learners’ needs, analyzing the discourse and linguistic features of the

texts, and developing strategies to help learners develop the knowledge and skills involved in using

[L_[ZHZ[OLIHZPZMVYH[OLU[PJHUKTLHUPUNMSJVTTUPJH[PVU(JJVYKPUN[V-LLaHUK1V`JL

teaching from a text-based approach involves:

• teaching explicitly about the structures and grammatical features of spoken and written texts;

• linking spoken and written texts to the cultural context of their use;

• designing units of work which focus on developing skills in relation to whole texts;

• providing students with guided practice as they develop language skills for meaningful

communication through whole texts.

This approach is seen in Mickan (2013, 48–57), who describes a syllabus developed to prepare

1HWHULZLUKLYNYHKH[LZMVYHUV]LYZLHZZ[K`WYVNYHT[OH[PU[LNYH[LKSHUNHNLL_WLYPLUJLZ^P[O

local sightseeing in an Australian city. Core texts used in the program included the following:

• Copies of transcripts of classroom practices – discourse with a focus on teacher instructions;

NYVW^VYR[HSRYLXLZ[PUNJSHYPÄJH[PVUHUKHZZPZ[HUJLPUP[PH[PUNLUXPYPLZHZ^LSSHZYLZWVUKPUN

to enquiries.

• Examples of oral reports, with transcripts, on visits to wildlife park.

• Procedural texts illustrating the processes of grape production and wine production.

• Descriptions of tourist destinations around Adelaide.

Mickan does not describe where and how the transcripts referred to were obtained, who transcribed

them, or how they were used: obviously the logistics and time involved would be considerable.

As we saw above, the notion of text types is central to the planning of a text-based syllabus, and the

organization of skill-based courses (e.g., courses in reading, writing, listening, or speaking) is often

based on text types (also referred to as genres) at the macro level. Other syllabus strands, such

as grammar and vocabulary, will be chosen depending on the nature of each skill. For example, in

WSHUUPUNHJVYZLHYVUKZWLHRPUNZRPSSZ[OLÄYZ[WSHUUPUNKLJPZPVUPUH[L_[IHZLKHWWYVHJOOHZ[V

do with determining the types of spoken texts the course will address based on the learners’ needs,

such as small talk, casual conversation, telephone conversations, formal conversation, transactions,

discussions, interviews, presentations, etc. Each text type has distinct characteristics. Other syllabus

Z[YHUKZ^PSSYLÅLJ[[OLUH[YLVMLHJONLUYL;OLZ`SSHIZHSZVZHSS`ZWLJPÄLZV[OLYJVTWVULU[ZVM

texts, such as grammar, vocabulary, topics, and functions; hence, it is a type of mixed syllabus, one

which integrates reading, writing, and oral communication, and which teaches grammar and other

features of texts through the mastery of texts rather than in isolation.

For example, in the case of the text type of conversation this would include at the micro level, opening

and closing conversations, topic choice, topic development, discourse management, turn taking,

back channeling, questioning, clarifying meaning. Other syllabus components for a speaking course

at the micro level could include functions, conversational routines, and vocabulary.

See Appendix 4 for procedures involved in teaching from a text-based syllabus.

Examples of a text-based approach

;L_[ZHZWSHUUPUNUP[ZPUJYYPJSTKLZPNUOH]LILLUZLKPUHUTILYVMKPќLYLU[^H`ZHZV[SPULK

below.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-19-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 179

ESP and EAP courses. English for Special Purposes and English for Academic Purposes are obvious

cases where a text-based approach would be relevant. Such a course would be built around the

ZWVRLUHUK^YP[[LU[L_[[`WLZLUJVU[LYLKPUZWLJPÄJJVU[L_[Z(Z4PJRHUJVTTLU[Z

^P[O YLMLYLUJL [V ;)0 PU HJHKLTPJ JVU[L_[Z! ¸(JHKLTPJ Z[K` YLXPYLZ UKLYZ[HUKPUN HUK ZPUN

specialized discourses for participation in disciplinary practices … Academic language comprises

multiple texts and tasks embedded in disciplinary practices.”

Textbooks for a state curriculum. TBI has also been used as the framework for textbooks used in state

schools at both primary and secondary level (e.g., in Singapore).

A component of CBI and CLIL. A text-based approach is compatible with other approaches and can

be used as the basis for integrating content with language learning. Texts become the vehicle through

which learners engage with content.

Issues with a text-based approach

Critics have raised a number of questions about both the theory and the practice of TBI, principal

HTVUN^OPJOHYL[OVZLKLZJYPILKIYPLÅ`ILSV^

Focus on products rather than processes. As can be seen from the above summary, a text-based

approach focuses on the products of learning rather than the processes involved. Critics have pointed

out that an emphasis on individual creativity and personal expression is often missing from the TBI

model, which is heavily wedded to a methodology based on the study of model texts and the creation

of texts based on models.

Practicality. The practical demands of assembling and analyzing spoken and written texts might also

be unrealistic in many situations. Accounts given in Mickan (2013) make extensive use of transcripts

VMH[OLU[PJZWVRLU,UNSPZO^OPJO^VSKILKPѝJS[MVYTHU`[LHJOLYZ[VVI[HPU6U[OLV[OLYOHUK

a text-based approach lends itself readily to the design of textbooks and other materials, so some of

the planning required may not necessarily involve the teacher.

Conclusions

;OL Z`SSHIZ HWWYVHJOLZ PU [OPZ JOHW[LY VќLY KPќLYLU[ ZVS[PVUZ [V [OL WYVISLT VM KL]LSVWPUN H

rational approach to the design of a language course and syllabus. In the case of content-based,

[HZRIHZLKHUK[L_[IHZLKHWWYVHJOLZ[OLZ[HY[PUNWVPU[ZPULHJOJHZLKPќLY-VY*)0HUK*303

a focus on the communication and understanding of meaning and information initiates the process

of syllabus development. Other planning decisions, such as those related to lexis, grammar, and

texts, are dependent upon how meaning and content is presented. Methodology is not prescribed.

In the case of task-based approaches, the process of syllabus development starts with identifying

tasks. These are used to activate learning processes and also to prepare leaners for out-of-class

task performance. A cycle of classroom activities is prescribed. A text-based approach begins with

identifying text types, and classroom activities center on text analysis and text creation following a

WYLZJYPILKZL[VMWYVJLKYLZ*VTWL[LUJ`IHZLKHWWYVHJOLZKPќLYMYVTLHJOVM[OLHIV]LZ`SSHIZ

TVKLSZZPUJLPU[OPZJHZLZ`SSHIZKL]LSVWTLU[Z[HY[Z^P[OPKLU[PÄJH[PVUVMSLHYUPUNV[JVTLZHUK

YLSH[LK JVTWL[LUJPLZ :IZLXLU[ ZWLJPÄJH[PVU VM Z`SSHIZ JVU[LU[ KLWLUKZ VU [OL JVU[L_[ HUK

could include linguistic items and content, texts, and skills. Methodology is not prescribed.

In the next chapter we will consider other approaches to syllabus design and review the use of skills,

functions, grammar, vocabulary, and situation in syllabus design.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-20-320.jpg)

![180 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

Discussion questions

1. Go online and look at the (*;-3 7YVÄJPLUJ` .PKLSPULZ MVY ,UNSPZO ^^^HJ[ÅVYN

WISPJH[PVUZNPKLSPULZHUKTHUHSZHJ[ÅWYVÄJPLUJ`NPKLSPULZLUNSPZOZWLHRPUN HUK

read the descriptions for any level of one of the four macro-skills. Where would you place yourself

on the scale for any foreign language you speak?

2. How would you explain the notion of macro- and micro-level units of course organization to a

UV]PJL[LHJOLY.P]LL_HTWSLZMYVTZL]LYHSKPќLYLU[RPUKZVMJVYZLZ

3. You have been asked to plan a unit on climate change for an intermediate-level speaking class.

What skills and grammar could you link to this topic?

4. (YL*)0HUK*303PKLU[PJHS/V^KV`VUKLYZ[HUK[OLPYZPTPSHYP[PLZHUKKPќLYLUJLZ

5. @VHYLKL]LSVWPUNHJVTWL[LUJ`IHZLKJVYZLMVYYLZ[HYHU[Z[Hќ^HP[WLYZVUZ/V^^VSK

you identify the competencies they need to master in English? Give examples of what the

competencies would look like.

6. Give an example of a pedagogic task and a real-world task that could be used in designing (a)

a reading course and (b) a listening course.

7. 0U^OH[JPYJTZ[HUJLZKV`V[OPURH[HZRIHZLKHWWYVHJO^VSKILHTVZ[LќLJ[P]LISLHZ[

LќLJ[P]L

8. Choose a group of learners that you are familiar with. What kinds of spoken and written texts

KV`V[OPUR[OL`TVZ[MYLXLU[S`LUJVU[LYOH[RPUKZVMKPѝJS[PLZHYL[OLZL[L_[ZSPRLS`[V

pose for them?

9. Prepare a sample lesson plan based on each of the four syllabus models discussed in this

chapter, and compare them. What features do they have in common?

10. Read Case study 10 by Lindsay Miller at the end of this chapter.

• How were language and content integrated throughout the course?

• What language skills do you think the learners were likely to develop?

• What other areas of content do you think could be used in a similar way with this group

of learners?

11. Read Case study 11 by Rosa Bergadà.

• /V^KV[OLNVHSZVMOLYJVYZLHUK3PUKZH`»ZJVYZLKPќLY

• How does the course link content to language development?

• /V^KVLZ[OLJVYZLYLÅLJ[HSLHYULYJLU[LYLKHWWYVHJO

12. Read Case study 12 by Phil Chappell.

• /V^KVLZ[OLJVYZLYLÅLJ[H[L_[IHZLKHWWYVHJO[VJYYPJSTKLZPNU

• /V^KVLZ[OLJVYZLYLÅLJ[SLHYULYZ»ULLKZ

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-21-320.jpg)

![7 Course planning (1) • 181

APPENDIX 1 ;OL(*;-37YVÄJPLUJ`.PKLSPULZ – For Speaking

DISTINGUISHED

:WLHRLYZH[[OL+PZ[PUNPZOLKSL]LSHYLHISL[VZLSHUNHNLZRPSSMSS`HUK^P[OHJJYHJ`LѝJPLUJ`

HUK LќLJ[P]LULZZ ;OL` HYL LKJH[LK HUK HY[PJSH[L ZLYZ VM [OL SHUNHNL ;OL` JHU YLÅLJ[ VU

a wide range of global issues and highly abstract concepts in a culturally appropriate manner.

Distinguished-level speakers can use persuasive and hypothetical discourse for representational

purposes, allowing them to advocate a point of view that is not necessarily their own. They can

tailor language to a variety of audiences by adapting their speech and register in ways that are

culturally authentic.

Speakers at the Distinguished level produce highly sophisticated and tightly organized

extended discourse. At the same time, they can speak succinctly, often using cultural and historical

references to allow them to say less and mean more. At this level, oral discourse typically resembles

written discourse.

A non-native accent, a lack of a native-like economy of expression, a limited control of deeply

embedded cultural references, and/or an occasional isolated language error may still be present at

this level.

SUPERIOR

:WLHRLYZ H[ [OL :WLYPVY SL]LS HYL HISL [V JVTTUPJH[L ^P[O HJJYHJ` HUK ÅLUJ` PU VYKLY [V

WHY[PJPWH[LMSS`HUKLќLJ[P]LS`PUJVU]LYZH[PVUZVUH]HYPL[`VM[VWPJZPUMVYTHSHUKPUMVYTHSZL[[PUNZ

MYVT IV[O JVUJYL[L HUK HIZ[YHJ[ WLYZWLJ[P]LZ ;OL` KPZJZZ [OLPY PU[LYLZ[Z HUK ZWLJPHS ÄLSKZ VM

competence, explain complex matters in detail, and provide lengthy and coherent narrations, all with

LHZLÅLUJ`HUKHJJYHJ`;OL`WYLZLU[[OLPYVWPUPVUZVUHUTILYVMPZZLZVMPU[LYLZ[[V[OLT

such as social and political issues, and provide structured arguments to support these opinions. They

are able to construct and develop hypotheses to explore alternative possibilities.

When appropriate, these speakers use extended discourse without unnaturally lengthy hesitation

to make their point, even when engaged in abstract elaborations. Such discourse, while coherent,

TH` Z[PSS IL PUÅLUJLK I` SHUNHNL WH[[LYUZ V[OLY [OHU [OVZL VM [OL [HYNL[ SHUNHNL :WLYPVY

level speakers employ a variety of interactive and discourse strategies, such as turn-taking and

separating main ideas from supporting information through the use of syntactic, lexical, and

phonetic devices.

Speakers at the Superior level demonstrate no pattern of error in the use of basic structures, although

they may make sporadic errors, particularly in low-frequency structures and in complex high-

frequency structures. Such errors, if they do occur, do not distract the native interlocutor or interfere

with communication.

ADVANCED

Speakers at the Advanced level engage in conversation in a clearly participatory manner in order to

communicate information on autobiographical topics, as well as topics of community, national, or

international interest. The topics are handled concretely by means of narration and description in the

THQVY[PTLMYHTLZVMWHZ[WYLZLU[HUKM[YL;OLZLZWLHRLYZJHUHSZVKLHS^P[OHZVJPHSZP[H[PVU

with an unexpected complication. The language of Advanced-level speakers is abundant, the oral

paragraph being the measure of Advanced-level length and discourse. Advanced-level speakers have

ZѝJPLU[JVU[YVSVMIHZPJZ[YJ[YLZHUKNLULYPJ]VJHISHY`[VILUKLYZ[VVKI`UH[P]LZWLHRLYZVM

the language, including those unaccustomed to non-native speech.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024556.008 Published online by Cambridge University Press](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/courseplanning1-240128032411-7b2d0457/85/course_planning_-Content-based-syllabus-22-320.jpg)

![182 • Curriculum Development in Language Teaching

ADVANCED HIGH

Speakers at the Advanced High sublevel perform all Advanced-level tasks with linguistic ease,

JVUÄKLUJLHUKJVTWL[LUJL;OL`HYLJVUZPZ[LU[S`HISL[VL_WSHPUPUKL[HPSHUKUHYYH[LMSS`HUK

accurately in all time frames. In addition, Advanced High speakers handle the tasks pertaining to

the Superior level but cannot sustain performance at that level across a variety of topics. They

may provide a structured argument to support their opinions, and they may construct hypotheses,

but patterns of error appear. They can discuss some topics abstractly, especially those relating to

[OLPYWHY[PJSHYPU[LYLZ[ZHUKZWLJPHSÄLSKZVML_WLY[PZLI[PUNLULYHS[OL`HYLTVYLJVTMVY[HISL

discussing a variety of topics concretely.