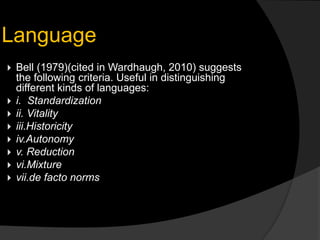

The document discusses the differences between language and dialect, and provides seven criteria proposed by Bell (1979) to distinguish languages from dialects: standardization, vitality, historicity, autonomy, reduction, mixture, and de facto norms. It also discusses the implications of language attitudes for language teaching, suggesting that teachers should promote motivation, discover the languages relevant to students, and expand opportunities for students to use multiple language forms.