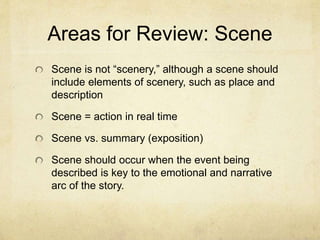

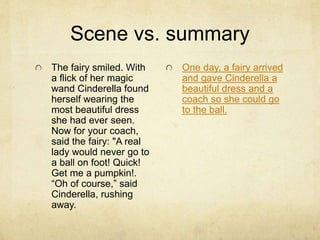

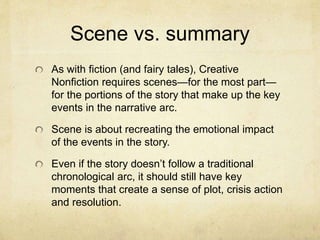

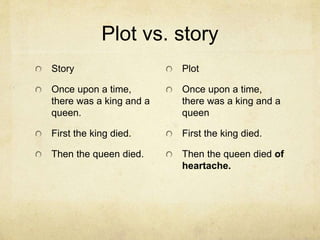

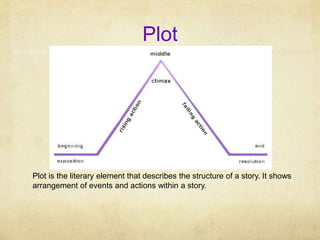

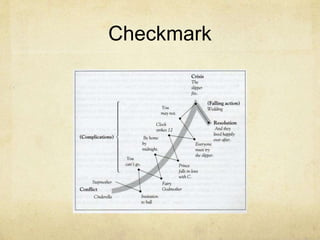

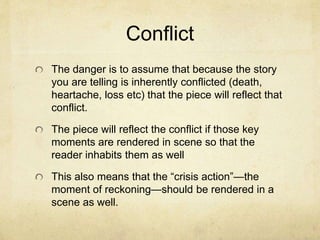

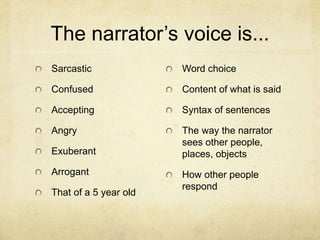

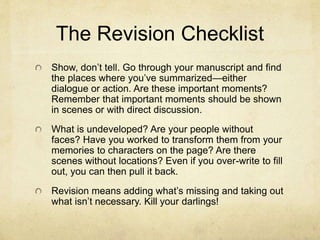

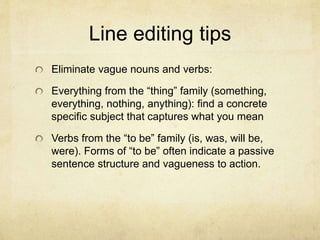

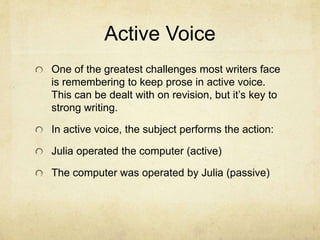

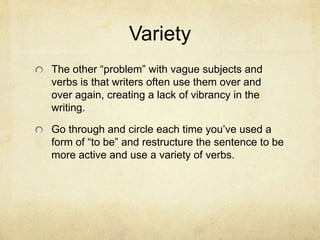

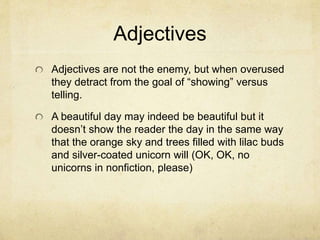

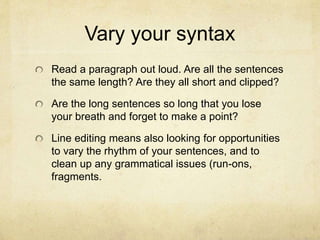

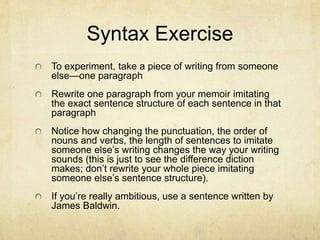

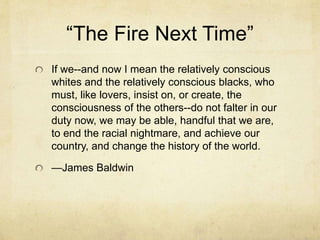

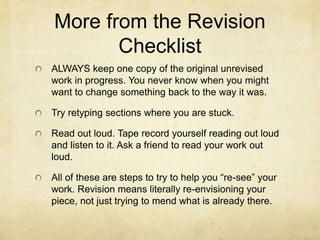

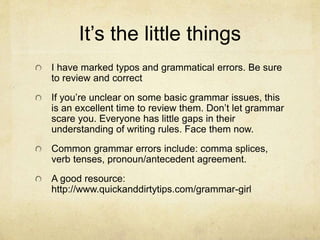

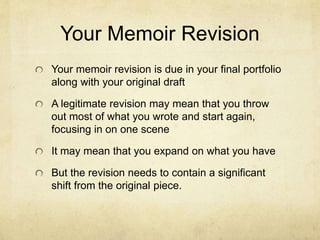

The document provides guidance on revising creative non-fiction writing. It discusses key elements to focus on in revision such as scenes, characters, voice, plot, and theme. Scenes should recreate emotional impact through action in real time rather than summary. Revision requires examining larger elements like character development and ensuring the story has an emotional climax. The checklist offers tips for line editing to eliminate vague language and ensure variety in syntax and word choice. Overall, revision is about re-envisioning the work rather than just editing what is there.