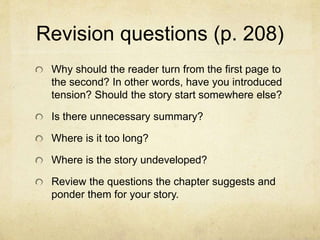

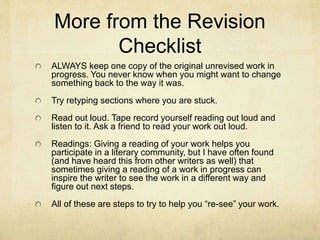

The document provides guidance on the revision process for creative writing. It emphasizes that revision is about consciously changing and improving the work after the initial draft, such as by addressing questions about tension, length, character development, and theme. Theme refers to the overarching idea or message of the story, which writers can uncover by analyzing what their story says about its central topic. The revision process should start with larger elements of fiction before finer details, and understanding the theme can help writers make choices that enhance and support it. A variety of techniques are suggested for revising, such as showing rather than telling, developing underwritten parts, removing unnecessary elements, and getting outside perspectives by reading work aloud or giving readings.