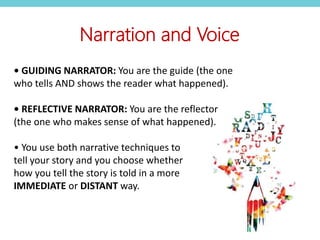

The document provides guidance on narrative techniques for storytelling, including:

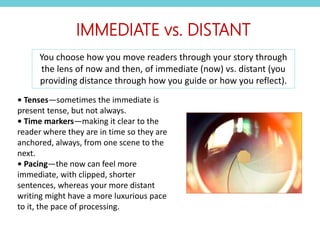

- Using a guiding narrator to lead the reader through time and summarize passages of time.

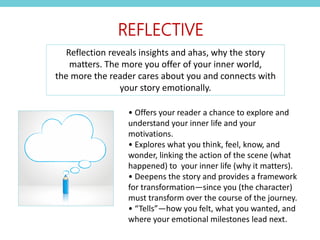

- Using a reflective narrator to reveal insights and allow the character to transform over the course of their journey.

- Choosing between an immediate or distant narrative voice and how to convey pacing and time through verb tenses and time markers.

- Painting sensory details to heighten the prose and using strong verbs and nouns with adjectives and adverbs sparingly.

- Offering exercises for writers to practice different narrative perspectives and techniques.

![Educated,

Tara Westover

Page 242

[Professor tells her she is valuable, and

she has a right to be at Cambridge, and

she can create the self she wants to be.]

I wanted to believe him, to take his

words and remake myself, but I’d never

had that kind of faith. No matter how

deeply I interred the memories [of the

past], how tightly I shut my eyes against

them, when I thought of my self the

images that came to mind were of that

girl, in the bathroom, in the parking lot.

I couldn’t tell Dr. Kerry about that

girl. I couldn’t tell him that the reason I

couldn’t return to Cambridge was that

being here threw into great relief every

violent and degrading moment of my life.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/voiceclass4-200526123213/85/Class-4-Mastering-Voice-8-320.jpg)

![What Comes Next

and How to Like It,

Abigail Thomas

[Following a stressful interaction with

her daughter]:

Page 166

Despite my good intentions I find a

cigarette on the floor of the living room.

A cigarette is to smoke, so I smoke it

immediately. I feel the dark god of

nicotine raise himself on one elbow in

my bloodstream. What took you so

long, girl? he asks lazily. He has those

bedroom eyes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/voiceclass4-200526123213/85/Class-4-Mastering-Voice-9-320.jpg)