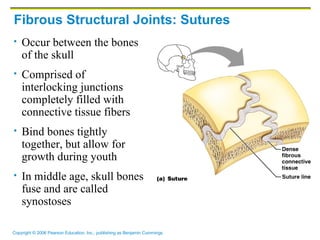

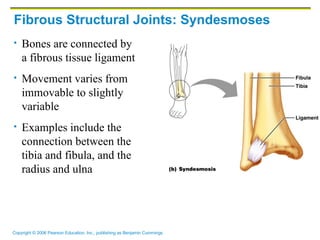

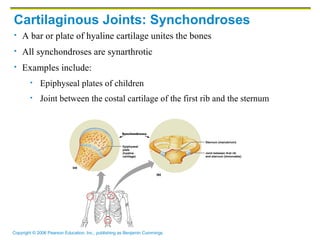

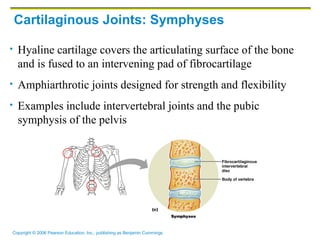

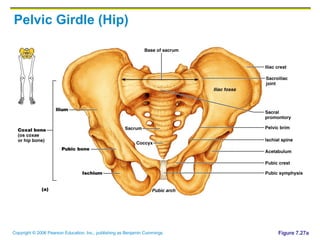

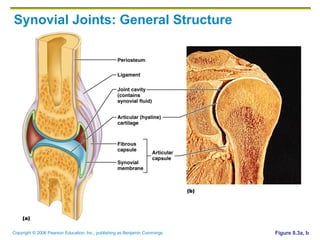

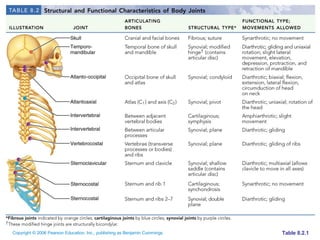

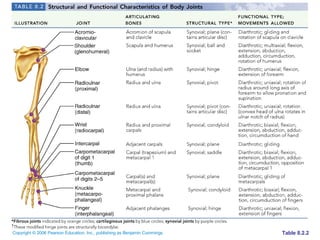

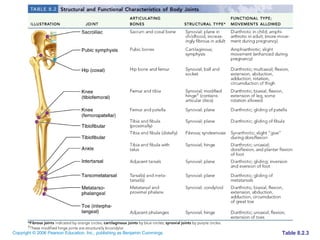

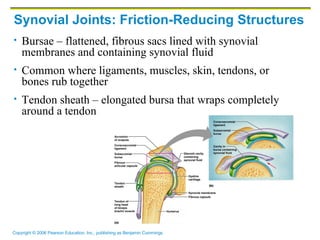

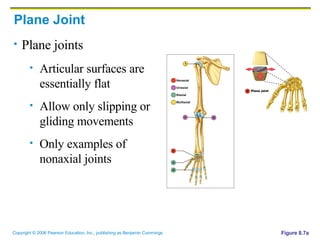

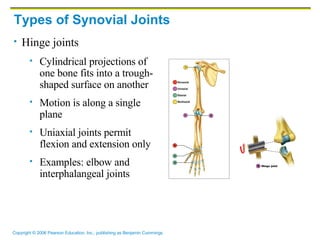

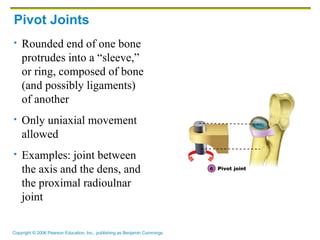

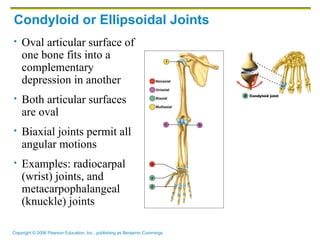

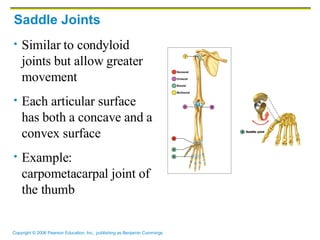

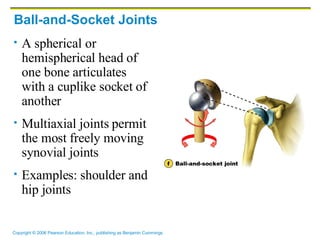

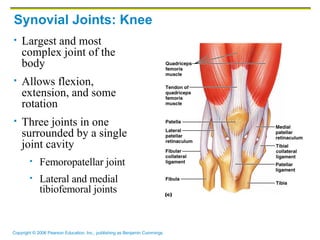

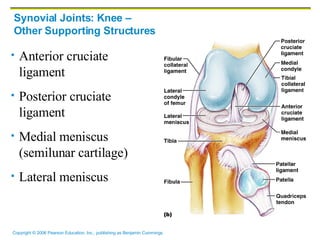

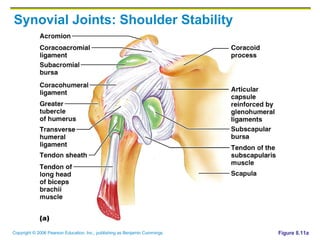

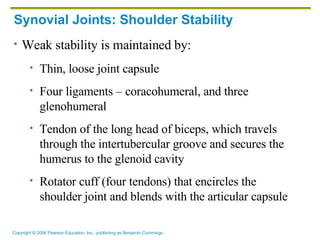

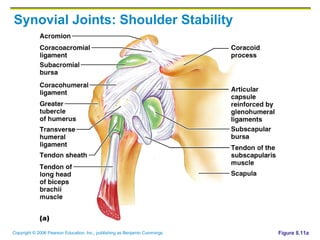

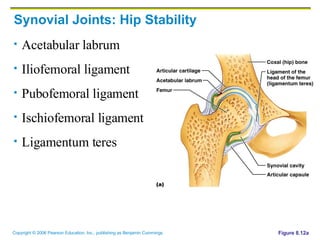

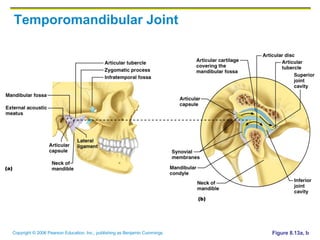

The document summarizes the structure and classification of joints in the human body. It discusses the three main types of joints - fibrous, cartilaginous, and synovial joints. Synovial joints are further classified based on their structure and degree of movement allowed. Common joint injuries like sprains and dislocations are also outlined along with inflammatory and degenerative joint conditions such as arthritis.