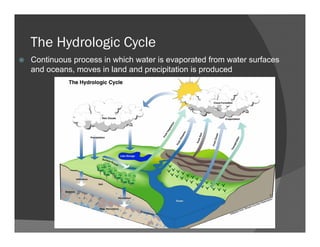

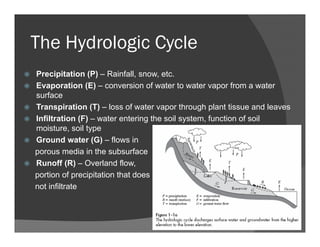

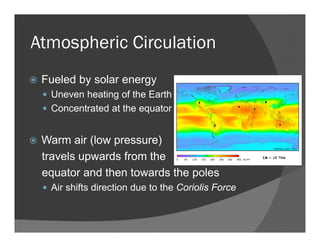

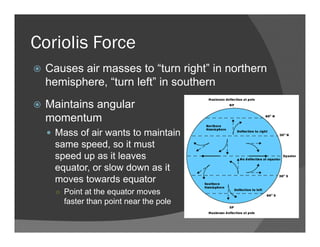

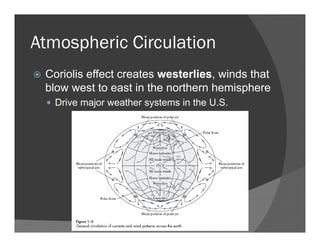

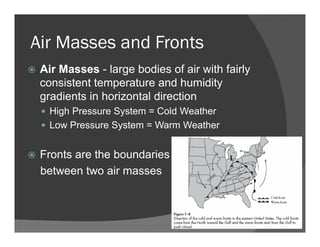

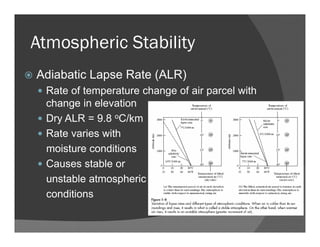

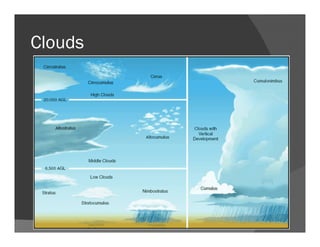

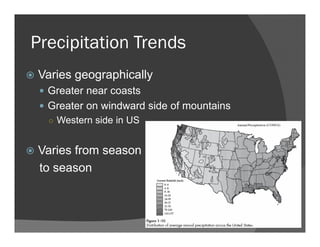

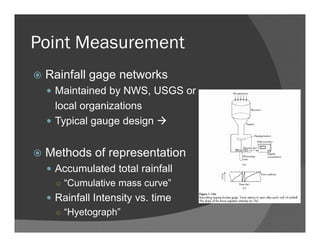

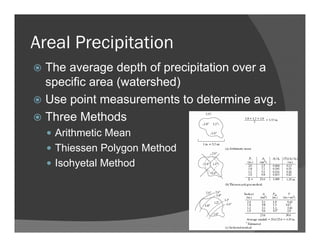

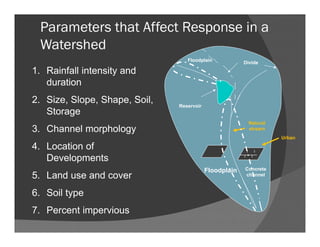

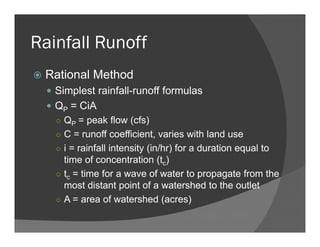

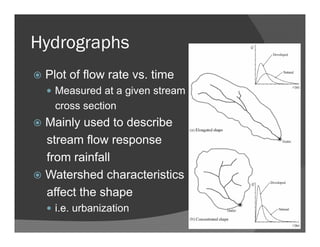

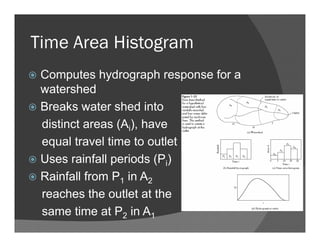

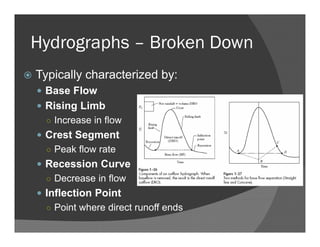

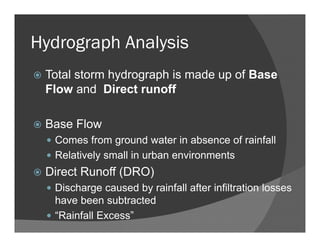

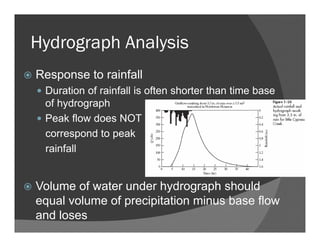

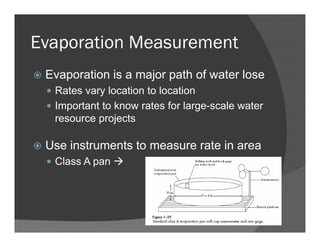

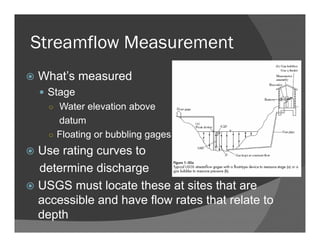

This document provides an overview of hydrology and floodplain analysis. It discusses the hydrologic cycle and key concepts in hydrology like precipitation, infiltration, evaporation and transpiration. Atmospheric processes that produce precipitation like humidity, pressure, temperature and atmospheric circulation are explained. Measurement techniques for rainfall, streamflow, infiltration and evaporation are also summarized. The role of watershed characteristics in determining how rainfall produces runoff and the hydrograph is then outlined.