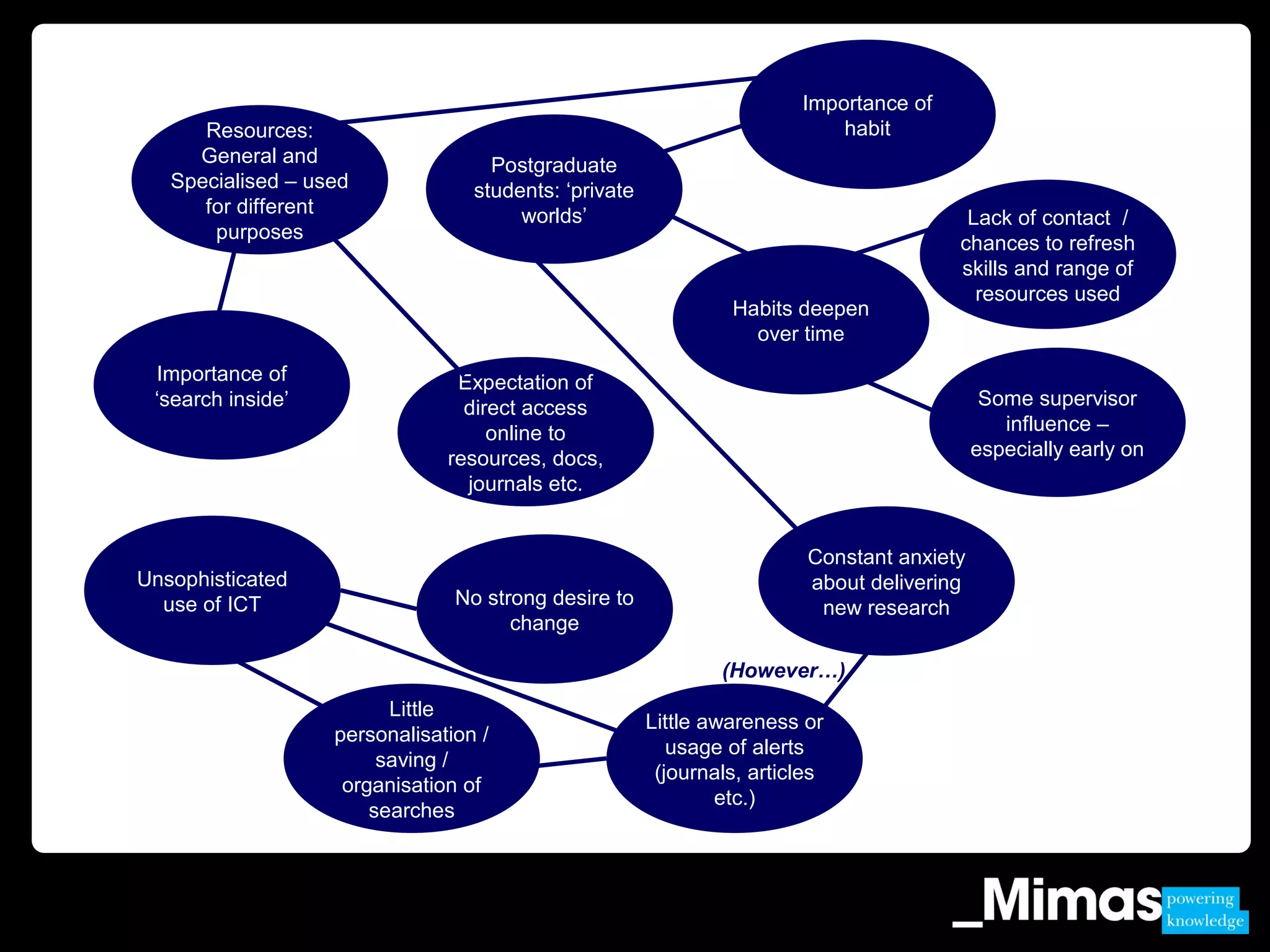

Changing user behavior on the web poses challenges for developing online information literacy tools. Research shows that users have poor understanding of their information needs, difficulties evaluating long search results, and unsophisticated mental maps of the internet. Younger users in particular spend little time evaluating information and have become reliant on search engines like Google over library resources. Developing tools requires addressing issues like entrenched habits, lack of skills training, and preference for familiar search interfaces.

![IL of young people not improved; little time spent on

evaluating information; people have poor understanding of

their information needs; difficulties in assessing relevance

when faced with a long list of search hits; unsophisticated

mental maps of what the Internet is failing to appreciated

that it is a collection of networked resources from different

providers; search engines become the primary brand

associated with the Internet; people do not find library

sponsored resources intuitive and prefer to use Google

instead: the familiar solution ….

[CIBER (2008). Information Behaviour of the Researcher of the Future]

Research reports](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/carolinewilliamsmimasfinalversion-170915133114/75/Changing-user-behaviour-on-the-web-what-does-this-mean-for-the-development-of-online-information-literacy-tools-Williams-4-2048.jpg)

![“HEIs, colleges and schools treat information literacies as

a priority area and support all students so that they are

able, amongst other things, to identify, search, locate,

retrieve and especially, critically evaluate information

from the range of appropriate sources … and organise and

use it effectively.”

[Committee of Inquiry into the Changing Learner Experience (May 2009). Higher

Education in a Web 2.0 World. March 2009. http://www.clex.org.uk]

Research reports](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/carolinewilliamsmimasfinalversion-170915133114/75/Changing-user-behaviour-on-the-web-what-does-this-mean-for-the-development-of-online-information-literacy-tools-Williams-5-2048.jpg)

![» UGs largely ignorant of how to undertake effective

internet searches

» UGs claimed that their typical practice would be to ‘throw

a few key words’ at a search engine and quickly scan the

results

Common search practices

“The more you use [Amazon] the more it gets

to understand you.” (PG)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/carolinewilliamsmimasfinalversion-170915133114/75/Changing-user-behaviour-on-the-web-what-does-this-mean-for-the-development-of-online-information-literacy-tools-Williams-22-2048.jpg)

![“The mobile phone is undoubtedly [a] strong

driving force, a behaviour changer…Library users

will soon be demanding that every interaction

can take place via the cell phone”

Mobile use](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/carolinewilliamsmimasfinalversion-170915133114/75/Changing-user-behaviour-on-the-web-what-does-this-mean-for-the-development-of-online-information-literacy-tools-Williams-26-2048.jpg)

![Summary

“You fall into habits don’t you? …

once you fall into a habit it’s difficult

to break it”. [Post-graduate student]”

“I can’t think of anywhere that would

have everything I need. You’re only

one click away with Google”. [Post-

graduate student]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/carolinewilliamsmimasfinalversion-170915133114/75/Changing-user-behaviour-on-the-web-what-does-this-mean-for-the-development-of-online-information-literacy-tools-Williams-32-2048.jpg)