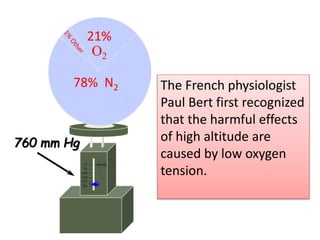

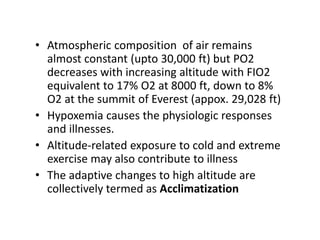

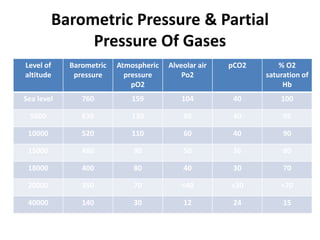

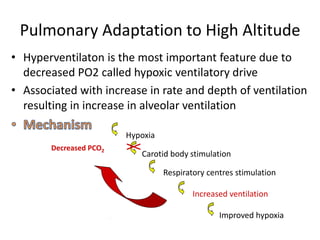

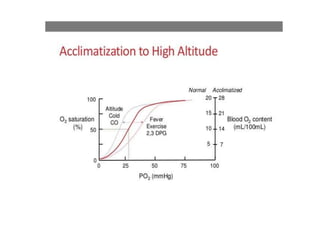

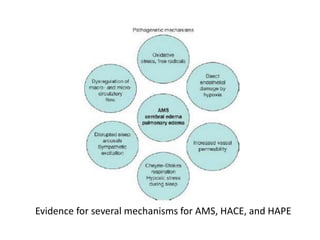

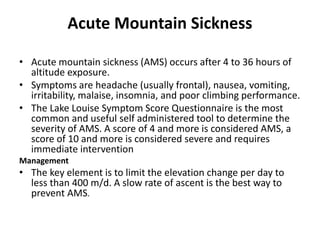

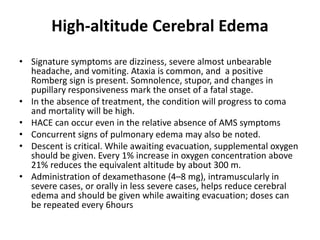

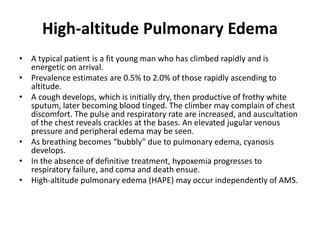

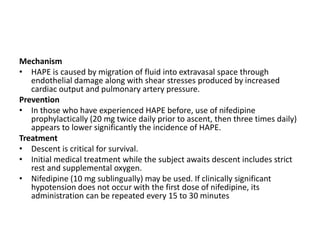

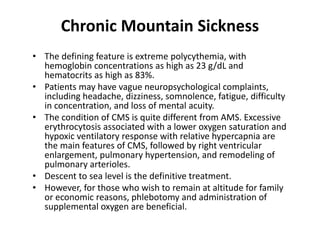

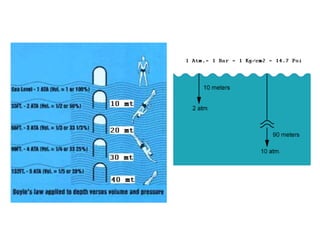

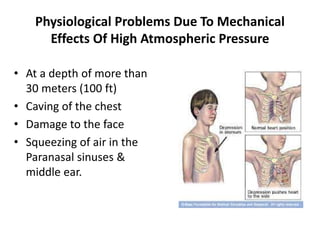

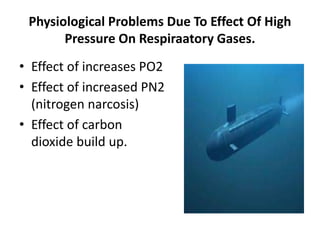

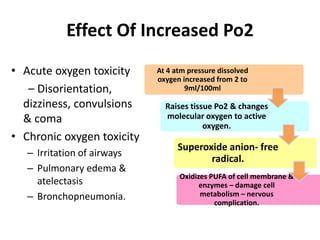

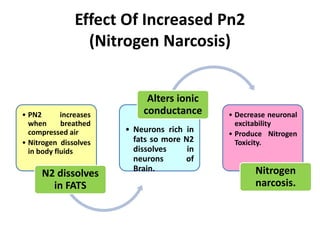

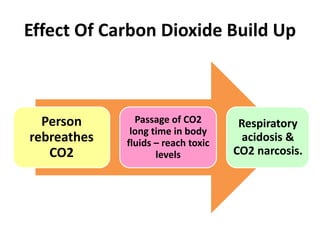

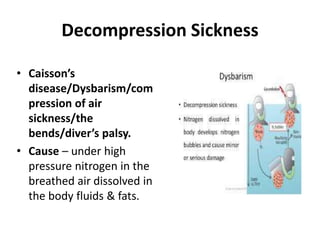

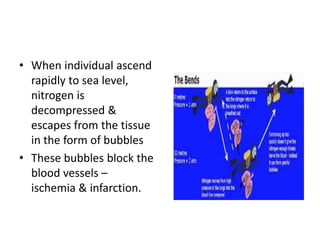

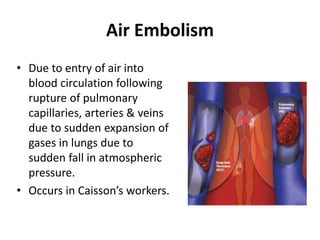

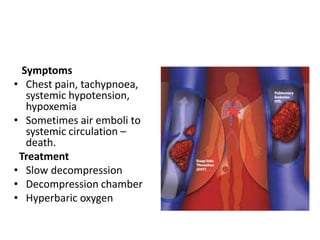

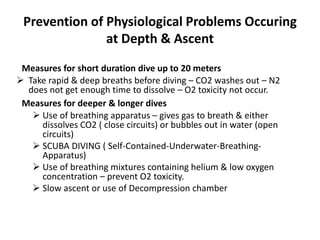

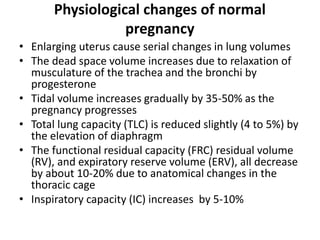

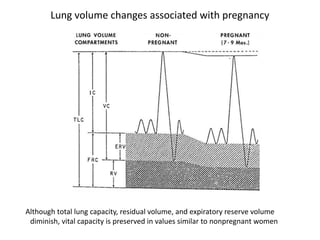

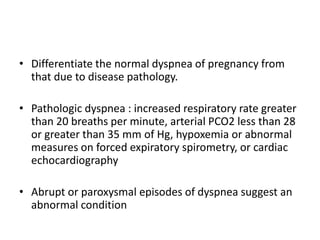

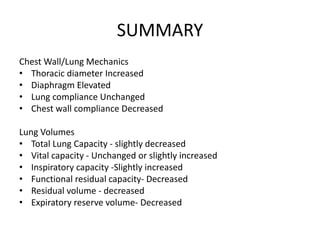

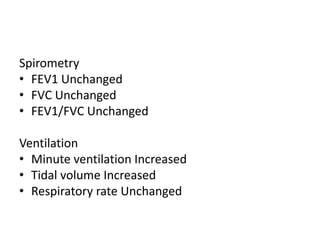

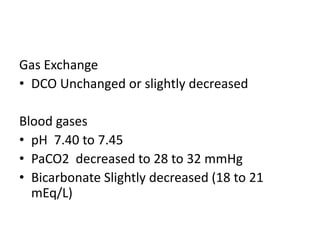

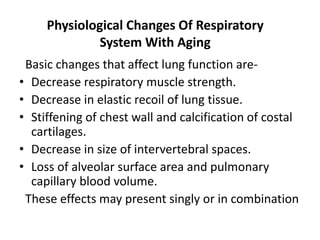

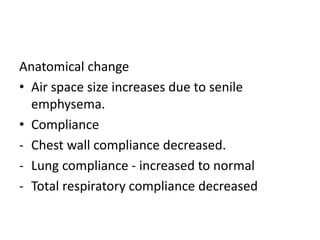

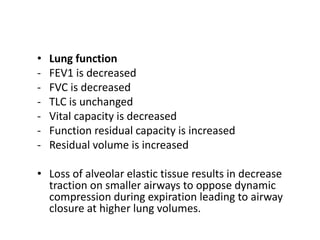

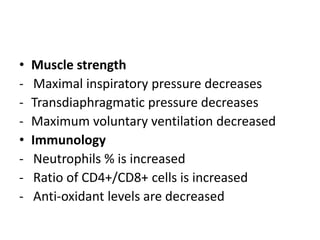

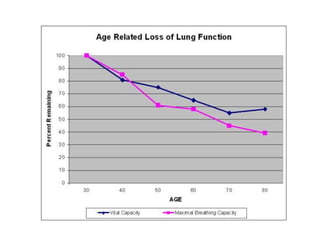

The document discusses changes in the respiratory system due to various physiological conditions such as high altitude, deep sea diving, pregnancy, exercise, and aging. It details the physiological adaptations and disorders associated with altitude exposure, including acute and chronic mountain sickness, as well as the effects of increased barometric pressure during deep diving. Additionally, it outlines anatomical and physiological changes during pregnancy that affect lung volumes and breathing mechanics.