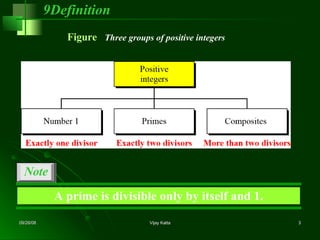

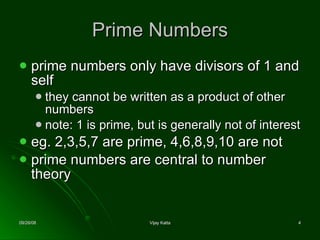

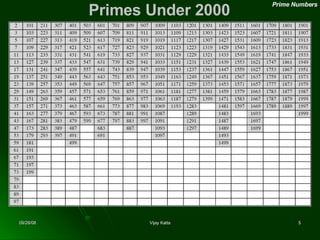

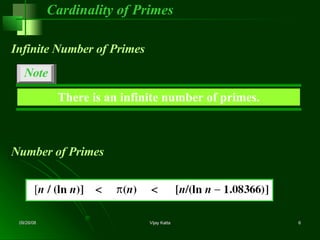

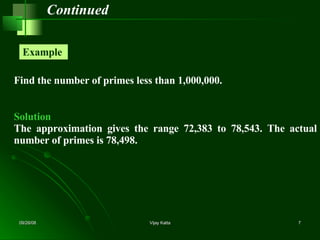

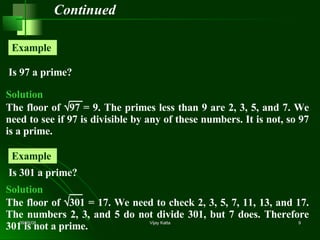

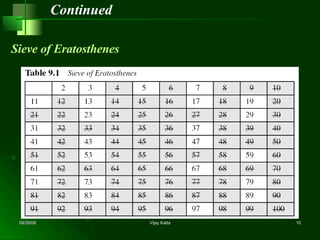

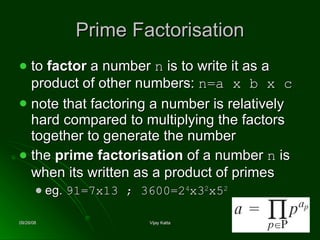

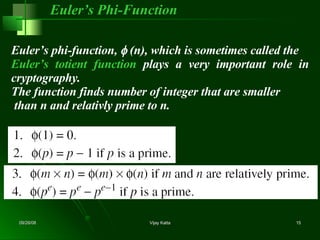

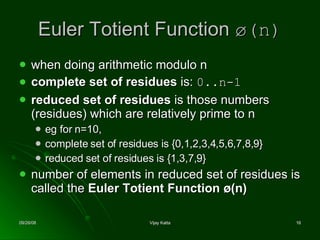

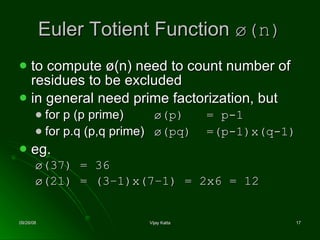

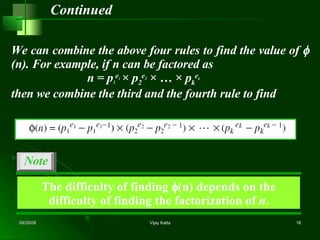

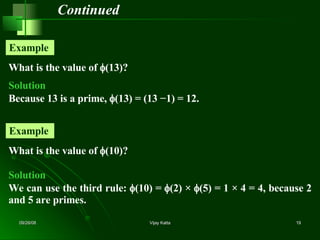

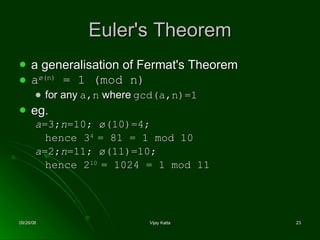

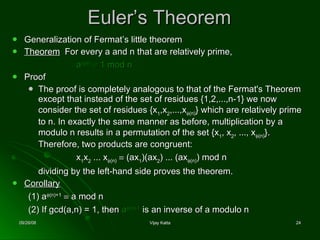

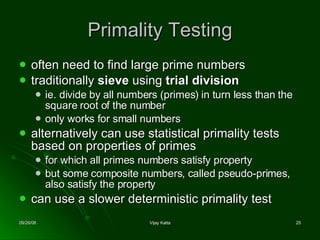

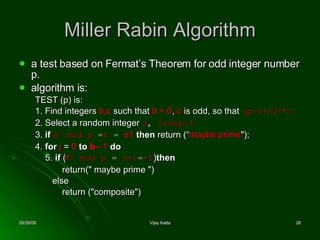

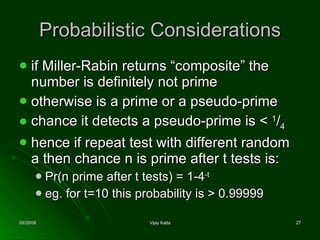

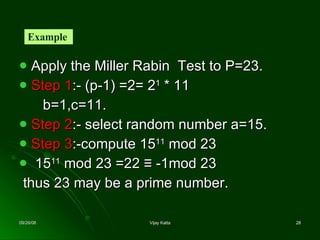

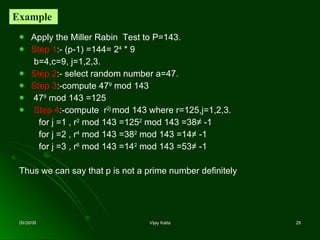

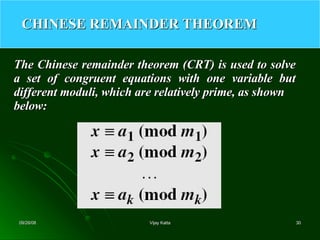

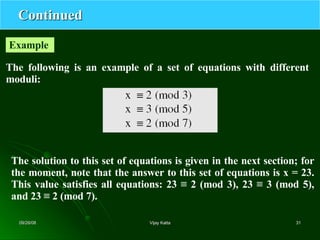

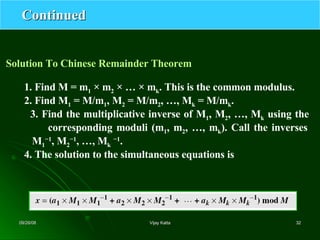

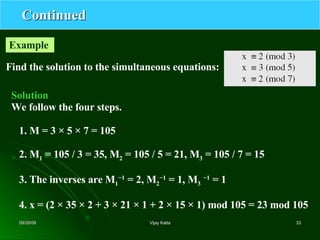

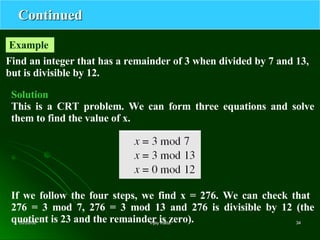

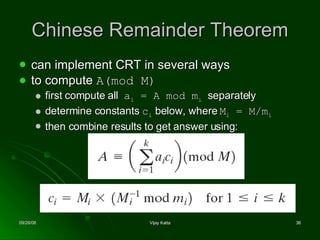

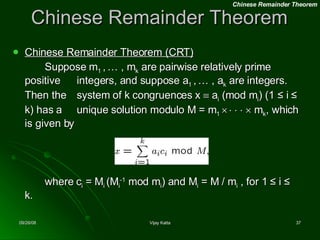

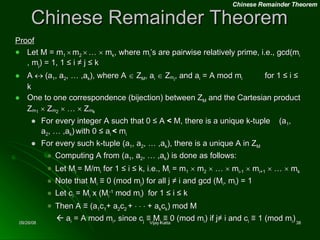

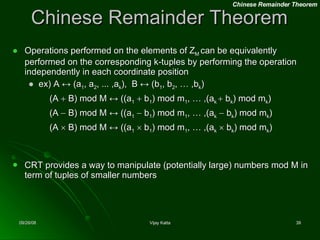

The document discusses several topics in cryptography including prime numbers, primality testing algorithms, factorization algorithms, the Chinese Remainder Theorem, and modular exponentiation. It defines prime numbers and describes algorithms for determining if a number is prime like the trial division method and Miller-Rabin primality test. Factorization algorithms are used to break encryption. The Chinese Remainder Theorem can be used to solve simultaneous congruences and speed up computations performed modulo composite numbers. Euler's theorem and its generalization are also covered.

![Chinese Remainder Theorem Example Let m 1 = 37, m 2 = 49, M = m 1 m 2 = 1813, A = 973 , B = 678 M 1 = 49, M 2 = 37 Using the extended Euclid’s alg orithm M 1 -1 mod m 1 = 34, and M 2 -1 mod m 2 = 4 Taking residues modulo 37 and 49 973 (11, 42), 678 (12, 41) Add the tuples element-wise (11 + 12 mod 37, 42 + 41 mod 49) = (23, 34) To verify, we compute (23, 34) (a 1 c 1 + a 2 c 2 ) mod M = (a 1 M 1 M 1 -1 + a 2 M 2 M 2 -1 ) mod M = [(23)(49)(34) + (34)(37)(4)] mod 1813 = 1651 which is equal to (678 + 973) mod 1813 = 1651 Chinese Remainder Theorem](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch08-1222347383543794-8/85/Ch08-40-320.jpg)